Introduction

The skin is the primary defense for the human body (Bluestein & Javaheri, 2008). Once this defense is breached, a person is open to a wide range of pathogens, some which were previously normal flora turning pathogenic. Therefore, at any one point, measures should be taken to enhance the continuity and maintenance of skin integrity. One of the conditions limiting the nurses’ capability to maintain a hundred percent preservation of skin integrity is pressure ulcers. Pressure ulcers, also known as decubitus ulcers or pressure sores, refers to localized damage to the skin and its immediate tissue especially on bony prominence due to prolonged unrelieved pressure on those areas (Zuo & Meng, 2015). According to the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, a non-profit agency that focuses on matters caused by pressure sores, pressure injury, as a more relevant term to describe pressure ulcers since it is more encompassing to include the process and the ulcers (Kirman & Geibei, 2017).

The call to prevent the occurrence of pressure injuries is a nationwide campaign which has also been adopted by different countries outside the USA. In elaborating a preventive and management approach targeted at reducing pressure sore incidence and complications, it is crucial to understand the main factors associated with the development of pressure sores (Zuo & Meng, 2015). The primary contributor is impaired mobility probably due to sedation, immobilization, restrained, or recovering from traumatic injury. The second contributor is where the patient has contractures and/or spasticity. These two are associated with increased exposure to tissue trauma since contractures create rigidity, while contractures increase the patient’s affected tissue to shear forces and friction that risk tissue damage (Kirman & Geibei, 2017). The third contributor is the quality of the skin tissue. The skin quality is mainly affected by aging, paralysis, malnutrition, and extensive skin scarring like in burns (Qaseem, Humphrey, Forciea, Starkey & Denberg, 2015). These factors result in atrophy of the skin tissue which increases the skin vulnerability to ulceration (Kirman & Geibei, 2017). Minor traumatic forces are more likely to results in severe lacerations when the skin tissue is atrophied.

Malnutrition does not only result in poor skin quality but also affects the body immune system. The poor immune system reduces the rate of wound healing promoting chronicity of minor laceration occurred in pressure areas (Cooper, 2013). Anemia in malnutrition is associated with the reduced capacity to oxygenate the healing lacerations, which reduces the rate of healing (Bluestein & Javaheri, 2008). Furthermore, beddings dampness due to incontinence and poor changing of beddings also increases the risks of developing pressure sores. The most common bacteria identified to cause pressure ulcers include Proteus mirabilis, group D streptococci, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus, Pseudomonas, and Corynebacterium (Park-Lee & Caffrey 2009).

The prognosis of pressure sores is based on the pressure sore staging, which is further worsened by the presence of comorbidity status, especially when the other condition increases bacteremia. In stage I; the pressure injury is characterized by persistent erythema of the skin that does not disappear even with pressure release. At this stage, the skin is intact. In stage II, the skin loses partial thickness and present as erythematous with abrasion, blister or shallow crater. In stage III, there is full thickness of skin loss leaving the subcutaneous tissue exposed as a deep crater. In stage IV, there is full thickness of skin and subcutaneous loss that results in exposure of the underlying muscle or bone (Park-Lee & Caffrey, 2009).

Pressure ulcers that develop in healthcare facilities are not covered by Medicaid and Medicare Services, which increase the out-of-pocket cost and facility financing cost (Life Healthcare, 2016). The injuries are associated with increased risk of infections; increased cost of care, dissatisfaction in care, and low institutional standards among other directs impacts. Probable complications for a delayed response or ineffective interventions include autonomic dysreflexia, osteomyelitis, pyarthrosis, sepsis, malignant transformation and anemia (Balzer & Kottner, 2015). In summary, pressure ulcers are a major health concern, which needs to be appropriately managed.

The present report reviews a pilot change project that tracks the implementation of a pressure ulcer management intervention. The paper incorporates all the major elements of a DNP project development, including the discussion of the practice problem, the introduction of a PICOT question, and the review of appropriate literature and settings. Moreover, the report considers the theoretical framework that guided the project and the change model that was chosen for it. Eventually, the paper describes the project’s procedures and results, reviews its limitations, and offers conclusions and recommendations.

Significance of the Practice Problem

The most common places where the patient develops pressure sores include the intensive critical care unit, chronic care units, and nursing homes (Qaseem, Humphrey, Forciea, Starkey & Denberg, 2015). Kirman and Geibei (2017) estimate that at least one million cases of pressure ulcers are reported each year in the United States of America (USA). The hospitalized populations are estimated to have an incidence of pressure ulcers ranging from 3.5% to 69% (Kirman & Geibei, 2017). The critical care patients have an incidence rate of 33% in the USA hospitals (Kirman & Geibei, 2017). Statistics from National Nursing Home Survey reported by Park-Lee & Caffrey (2009) indicate that 11% of the nursing homes in the USA in 2004 had patients battling pressure ulcers. In these facilities, most of the pressure ulcers were stage I and stage II accounting for 50% of the pressure ulcers reported. These statistics may be underreported given that pressure sores are considered as an indicator of poor performance.

Hospital-acquired pressure ulcers increase the cost of care at the patient and institutional level. Leaf Healthcare (2016) reported an extra 4-10 days of hospital stay following the development of pressure ulcers, which further risk the development of other hospital related conditions. The cost of pressure ulcers is mainly dependent on the severity of the condition with estimates ranging from United State Dollar (USD) 2000 – USD 20000 per ulcer (Leaf Healthcare, 2016). Data from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ, 2014) indicate that cost of care for each pressure sore can go from $20,900 to $151,700. One of the main reasons why Medicaid and Medicare services terminated reimbursement for hospital-acquired pressure sores in 2008 was the high-cost rate, which was estimated to escalate patient care by over $43,180. Furthermore, pressure ulcers cases (17000 annually) are the second most common lawsuits filed on health matters after death cases (AHRQ, 2014). The estimated compensation from these litigation procedures is USD $250,000 with over 85% of the cases ending in the patient being compensated (AHRQ, 2014).

Apart from these costs, about 60,000 patients succumb due to pressure ulcers annually in USA (AHRQ, 2014). An estimated 50% of stage two ulcers and over 95% of stage three and four of these wounds take more than 8 weeks to heal, which exposes the patient to poly-pharmacy, antibiotic resistance, risks of adverse effects among other uncalled-for complications. The pain is also under significant levels of stress, pain, suffering, and notable deterioration of the quality of life (Brem, Maggi, Nierman, et al., 2010).

Significance to Patients

These statistics highlight the direct need to address the issue of pressure ulcers. The most effective approach to handling the pressure ulcers is through an effective preventive approach, given the increased delay in healing and the complications arising once an individual develops pressure ulcers. To the individual patients suffering from pressure ulcers, this project will help in identifying the best approach that they can have the pressure sores problem addressed. A more effective approach is more likely to relief patients from health sufferings, financial sufferings, and eases the impact of the condition on the family members. It is expected that the outcomes of this project will result in a more adaptable and convenient approach to addressing pressure ulcers, which will, in the end, culminates to improving the quality of care for the benefit of the patient population.

Significance to Workforce Offering Care to Pressure Sore Patients

The nursing staff and the wider health professionals caring for the target population in this project also are to benefit from the completion of this project. First, a solution to the number of pressure ulcers patient will result in a decrease in workload. Consequently, the staff can dedicate their care to need patients, which will not only increase the quality of care for the pressure ulcer patients but for the entire hospital as well. The staffs will also have a framework, guideline or toolkit to follow while addressing pressure sores, which is more likely to reduce time wastage, increases effectiveness, and promote a collaborative approach in care delivery.

Significance to the Institutions

According to the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services as cited in Leaf Healthcare (2016), hospital-acquired pressure ulcers are classified as “never event”, which means the hospital cannot be reimbursed for offering pressure ulcers care. Therefore, a project that seeks to reduce the incidence and prevalence of pressure ulcers is of much importance. The project will help the institutions reduce the cost of covering pressure sores and associated complications. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act recommends for 1% deduction on Medicare reimbursement for those hospitals faring poorly in containing hospital-acquired pressure ulcers (Leaf Healthcare, 2016). This project is significant since its primary objective is to reduce the rate pressure ulcers in the identified study setting. Reduced workload will also result in increased staff performance culminating to institutional success. Also, an institution with reduced or low cases of pressure ulcers cases is likely to attract more clients and become a preferred destination for many patients in response to the positive public image.

Implications for Policymakers

The project is also critical to policy makers since they can use the project results in drafting effective pressure sore reduction. The policy makers can use the results in drafting the recommendations that should be used employed in attaining better results in preventing pressure sores.

PICOT Question

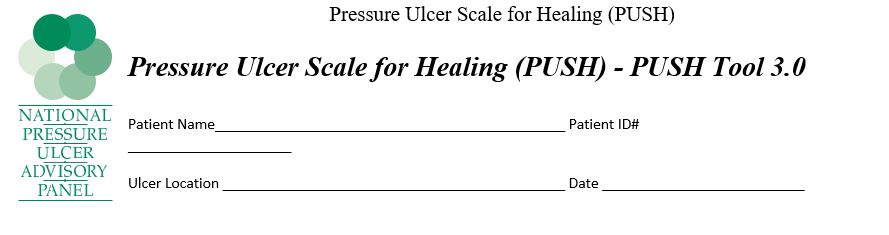

My PICOT Question: “For Registered Nurses and assistive personnel making home care visits for Jose Victor Perez DO, Miami Lakes, FL, does education on and implementation of the evidence based Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing (PUSH Tool) tool, along with audit and feedback, lead to improved efficacy in the management and care of pressure ulcers over an eight-week period?”

According to Riva, Malik, Burnie, Endicott and Busse (2012), the population/problem, intervention, comparison, outcome, and time (PICOT) format enhances the ability to comprehend the research question and identify the main aspects of the study that is assessed. For this project, the population – which refers to the group under evaluation in the project – was homebound pressure ulcers patients. Medicare definition of homebound is given as the patient must be in need of another person of medical equipment when leaving home or in instances where medical advice considers leaving home would aggravate the patient’s condition (Medicare Interactive, 2017). However, some of the instances such as leaving home for medical services, religious services, or attending adult day care centers are not disqualified for those categorized as homebound (Medicare Interactive, 2017). The population chosen for this project did not limit the age, so as to ensure that most patients were considered for the project. It was expected that most of the patients have comorbidities, given the pressure sores mostly occur as secondary infections. The problem under evaluation is the pressure sores, which has already been defined in the introduction section.

Intervention in the PICOT framing of the research questions refers to the action or treatment that the project seeks to implement for purposes of improving the current situation (Riva, et al., 2012). The chosen intervention is the implementation of an evidence-based tool, Pressure Ulcers Scale for Healing known as the PUSH Tool 3.0, for managing pressure sores that was consolidated from the literature review. According to Zuo and Meng (2015), use of an evidence-based practice approach enhances possibility of using the best practice. The practice for this case is expected not to expose the patients to extra risk and harm over and above those of the normal living. The change agent ensured that the patients were explained the intervention and the expected outcome, then requested to enroll voluntarily without any coercion, intimidation or manipulation.

In the PICOT format of the research question, the “C” stands for comparison: this is supposed to the alternative intervention that is compared with the primary intervention (Riva, et al., 2012). This is mostly the case when assessing the benefits of using one approach over the other in achieving the desired outcomes. For this project, the comparison outcome is the current practice, which does not employ any evidence-based tool. Having the comparison intervention is crucial since the primary intervention can have the benchmark where the resulting outcome can be gauged for their success.

The outcome refers to the expected results following the implementation of the proposed interventions (Riva, et al., 2012). For this project, the expected outcome was successful healing of pressure sores. Increased healing process that is effective will reduce hospital stay, reduce workload, reduced cost of care, reduced risk of poly-pharmacy and cut down antibacterial use. All these factors are more likely to increase patients’ satisfaction, staff satisfaction, and institutional success. Consequently, the project was expected to improve the quality of care and life of those affected and their families.

Time denotes the duration during which the outcome of the intervention was expected to last (Riva, et al., 2012). This duration is critical since a prolonged duration may result in an intervention that is not cost effective while a short duration may limit the full realization of the intervention’s benefits (Balzer & Kottner, 2015). Therefore, the project implementers ensured that the timeframe agreed for the project implementation was adequate to give the expected results. For this project, the timeline was 8 weeks. In a project by Palese, et al. (2015), stage II pressure ulcers took an average of 23 days (3 weeks) to heal. Therefore, the timeframe for this project was set for 8 weeks as a strategy for effective wound healing, including stage II, III and IV pressure ulcers. The timeline also allowed the project to cover an adequate patient population in order to have a sufficient sample size for drawing an adequate conclusion.

This project sought to address the PICOT question: “For Registered Nurses and assistive personnel making home care visits for Jose Victor Perez DO, Miami Lakes, FL, does education on and implementation of the evidence based Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing (PUSH Tool) tool, along with audit and feedback, lead to improved efficacy in the management and care of pressure ulcers over an eight-week period?”

Theoretical Framework

A theory is defined by Nilsen (2015), as a set of analytical principles designed to guide observation, understanding, and explanations regarding a given philosophy. An ideal theory should have a domain of application, links between the variables, and prediction of the implications of the theory. The use of a theoretical framework in a project enhances the philosophy propagated or foundation motivating the desire to undertake the project (Alligood, 2014). For the purpose of this project, the theory of choice informing the theoretical framework is the theory Self-Care Deficit (SCD) by Dorothea Orem. The theory dates back to 1971 when it was first published, but has undergone improvements to the current theory.

The SCD theory is based on the understanding that nursing as a profession addresses certain needs of the patients using the appropriate knowledge and skills. The theory has proven validity and reliability in nursing practice and also in the nursing education platforms (Queiros, Vidinha & Filho, 2014). Nurses advocate for the use of a nursing theory to guide in the execution of their roles and duties, which would improve the quality of care delivered. Alligood (2014), argues that SCD theory builds on the professionalism of nursing, by ensuring that the nursing care is guided by identified patients’ needs, and when these needs cannot be met by the patients without assistance.

The self-care deficit theory identifies five approaches that nurses may exploit in helping their patients (Alligood, 2014). The first approach involves acting and doing for the patients. This approach applies when the patient requires total care from the nurse, which means the nurse has to do the activity on behave of the patient (Alligood, 2014). For instance, immobilized patients may not manage to turn on their own; thus, the nurse has to establish a turning schedule to ensure the patient is relieved of pressure. The second approach involves guiding the patient, which applies when the patient needs just guidance to complete a care-based task. For instance, for patients that are mobile, they can be guided on how to apply oil on the pressure areas to reduce friction. The third approach involves the nurse supporting another to deliver the care needed. This is approach promotes collaborative care delivery where nurses work as a team with other health professionals.

The fourth approach entails the provision of an appropriate environment that promotes personal development crucial to meeting future health care demands (Shah, 2015). For instance, the nurse may ensure that the home environment for the homebound patients have access to pain medication for when the nurse is not available and having a family caregiver to attend to the patient when the nurse is away. The last approach is teaching the patient, which ensures the patient become empowered on matters pressure ulcers care among other relevant information (Alligood, 2014). For instance, the nurse may educate homebound pressure ulcer patients on how to reduce the risk of pressure sores such as creased beddings, wet beddings, and poor nutrition.

The use of this theory ensures that the delivery of care actively involves the patient’s contribution (Shah, 2015). The nurse assesses the patients’ needs and determines which approach of care delivery is best placed to meet the needs. In so doing, the patient owns up the management strategy empowering them all through and thereby improving their knowledge on the practice (Queiros, Vidinha & Filho, 2014).

Synthesis of the Literature

Articles Search Strategy

According to Zuo and Meng (2015), the sources of evidence in determining the best practice should be from reputable sources, especially given that in the current of high volumes of internet sources. For purposes of arriving at credible sources with quality and credible evidence needed for guiding on the best intervention, the researcher conducted a literature search. Three databases; Google Scholar, PubMed, and ScienceDirect were selected as the main sites where the articles needed would be retrieved. The decision to settle on these three databases was supported by the fact that the three databases have a high volume of health-related articles; thus, it would have been possible to retrieve full, high-quality articles. Secondly, the three databases are easily accessible and have in-built filter system, which promotes the ability to narrow down the large volume of potential articles to those precise articles that are touching on the subject matter.

Once the databases were selected, the researcher went ahead to identify the keywords that would be fed to the databases and executed for retrieving the relevant articles. The main keywords used included “patients” “pressure ulcers” “pressure sores” “bedsores” “toolkit” “incidence” “management” “quality of care” “healing” and “homebound.” Boolean Operators – OR and AND – were used to combine the search words into a string of words, which improved the precision of the search results (Ridley, 2012).

Search Results and Appraisal Process

From the three databases, 217 articles (Google Scholar – n = 67, ScienceDirect – n= 73, PubMed – n = 77) were retrieved, which were published since 2007 (the last ten years). The articles were systematically filtered and appraised for purposes of achieving the most appropriate article on basis of relevance, evidence strength, comprehensibility, validity, and reliability. The filtering and appraisal process that resulted in the selection of 11 articles is as illustrated in the flowchart below– Figure 1. Other filter systems that were used include English only articles, published between 2007 and 2017, full articles, primary studies, based on human subjects. The selected articles then underwent appraisal process, using the “Rapid Critical Appraisal Checklists,” which ensured the quality of the selected articles was convincing (see Appendix A).

This section now focuses on the 11 articles selected from the sources that were discussed. A mixed method study by Roberts, et al. (2017), assessing the effectiveness of a pressure ulcer prevention care bundle, nurses demonstrated the knowledge and willingness to use the care bundle. The bundle evaluated in this study took 10 minutes to deliver to each patient. 96.7% (n= 773) of the patients evaluated received pressure ulcers intervention, which was the implementation of the care bundle. This study supported the use of evidence-based study in the delivery of pressure ulcers care. In another study, Ohura, et al. (2011) conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving a control group of 30 patients with pressure ulcers grade III and IV and a treatment group of the same participant size and description. Their study evaluated the impact of having special nutrition preparation for a patient with pressure ulcers. The intervention group received calories in the range of Basal Energy Expenditure while the control group continued to receive normal diet for 12 weeks. The study demonstrated statistical significance with nutrition influence on pressure sores healing (p< 0.001) and maintaining body weight (p < 0.001). The study demonstrated the importance of proper nutrition in managing pressure ulcers.

Tsaras, et al. (2016) prospective study sought to determine the indicators that could be used to predict the occurrence of pressure ulcers in Intensive Care Unit. The prevalence of pressure ulcers in this unit was 24.3% for the period of one year that the evidence-based practice was in progress. The main factors determine to influence the incidence of pressure ulcers included increased age, with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.04 (CI: 1.01 – 1.07), prolonged length of hospitalization with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.17 (CI: 1.11 – 1.23), those under hemodialysis treatment with adjusted odds ratio of 4.09 (CI: 1.12 – 14.98), and anemia status given that increase in hematocrit value improved decrease risk of ulcers by roughly 9%. These findings concur with the previous study by Ohura, et al. (2011), which supported the vitality of proper nutrition in managing pressure ulcers.

Palese, Luisa, Ilenia, et al. (2015) conducted a secondary analysis of data collected from a multicenter RCT assessing healing time for stage II pressure ulcers. The study, which involved a sample size of 270 participants reported an average time of healing for stage II pressure ulcers to be 22.9 days. Of the total study sample, only 56.7% (n = 153) participant had their pressure ulcers heal within 10 weeks. These findings can inform the duration needed to implement management care for pressure ulcers. However, the result could have been affected by the fact that most of the patients were elderly (average age of 83.9 years) since old age is associated with decreased rate of cell regeneration. In addition, the approach of care was comparing the use of Tricum vulgaris as an additional treatment to the general wound cleaning and dressing practice.

In their study, Padula, et al. (2016) assess the effectiveness of adopted evidence-based practices following the decision by Medicaid and Medicare Services to discontinue reimbursing pressure ulcers care. This longitudinal study assessing 25 quality improvement interventions reported a significant reduction of cases of pressure ulcers on the implementation of the evidence-based practices. The statistical significance (p = 0.002) on the implementation of quality improvement interventions and change in Medicare reimbursement policy (p < 0.001) increase are clear indications that evidence-based practices have positive implication in the management of pressure ulcers. However, the result of reduced rates of pressure ulcers could also have resulted from the negative reinforcement with hospitals being compelled to adopt measures for reducing their hospital-acquired pressure sores. This could have resulted in reduced reporting for these conditions.

A randomized controlled trial by Bergstrom, et al. (2014), involving 942 patients recruited in the USA and Canadian nursing homes assessed the impact of routine hourly turning on patients on foam mattresses in reducing the incidence of pressure ulcers. The selected sample who were mainly females (77.6%) with an average age of 85.1 years demonstrated no statistical significance (p = 0.68) in 2-hourly, 3-hourly and 4-hourly turnings in reducing the risk and incidence of pressure ulcers. This does not, however, imply that the patient turning has not implications towards reducing pressure ulcers. The findings indicated that turning is crucial especially when a routine turning schedule is adopted to ensure the patients are relieved of pressure. Despite the fact that frequent turning is more likely to reduce pressure, less frequent turning is associated with uninterrupted sleep pattern, improved quality of life, reduced risk of friction, reduced staff workload, and saves time for other nursing interventions such as feeding and toileting.

In a pilot study by Ashbay, et al. (2012), three hundred and twelve participants were recruited for follow up running for one year which sought to assess the impact of negative pressure wound therapy compared to standard care interventions. The treatment intervention was observed to reduce the number of care follow-up, visits per week, duration of healing, and cost of care. Negative pressure wound therapy involves application of suction force when dressing the wound. The previous study informing Ashbay, et al. (2012) study support the therapy since it is linked with improved rate of wound closure, reduced wound infection, and reduced cost of wound care. Ashbay, et al. (2012) study demonstrates that adoption of this approach can be a worthy evidence-based practice towards effective pressure ulcers care.

Ghaisas, et al. (2014) conducted a cross-sectional analysis of data assessing the impact of lifestyle modification in pressure ulcers treatment. A total of 170 participants were involved in the study with 83 participants assigned to pressure ulcers prevention program and 87 assigned to the usual care. The study ran for one year of follow-up. The study identified four relationships between lifestyle and pressure ulcers care. One trend depicted positive wound healing in positive lifestyle modification. The second trend was described as negative or no change in wound healing in positive lifestyle modification. The third relationship involved positive wound healing in negative or no lifestyle modification and the last link was having negative or no pressure ulcers changes in minor or no lifestyle modification. The study concluded that lifestyle choices have significant impact on pressure sore healing. Notable lifestyle practices included smoking, alcohol intake, proper nutrition, psychological composure, relaxation techniques, and compliance to medical advice. This study is crucial in this project given that the project target homebound patients who may be exposed and tempted to indulge in unhealthy lifestyles.

In a society witnessing profound and progressive technology, Stern, et al. (2014) conducted a multi-method study involving 137 participants assessing the feasibility and effectiveness of adopting a remote pressure ulcers management approach. The study also assessed the impact of having a multidisciplinary team in managing pressure ulcers as opposed to the usual care which is mostly disfranchise approach in managing pressure ulcers. The study assesses the effectiveness of the approaches in reference to healing rate, pressure ulcers incidence, wound pain, hospital stay, and cost of care. There was significant reduction in cost of care by USD 650 per patient when using collaborative telemedicine approach. This study related to the current project given that both focuses on patients requiring long-term care on pressure ulcers.

Swafford, Culpepper and Dunn (2016) investigated the use of comprehensive program in prevention of hospital acquired pressure ulcers. The comprehensive program involved a combination of wound care practices such as Braden score, skin care protocol, fluidized re-positioners, and silicone gel application. These approaches are close to what can be termed as a bundle of care for pressure ulcers. The adoption of this comprehensive care reduced the rates of pressure ulcers by 69% while at the same time saving on cost of care. This demonstrates that use of evidence-based practice can have some considerable benefits when it comes to caring for those patients with pressure ulcers.

Roberts, et al. (2016) in a qualitative study involving 18 nurses from four different hospitals, assessed the perceptions of nurses in the using pressure ulcers prevention care bundle. Data was collected using interview approach and the result analyzed thematically. The nurses demonstrated strong conviction and support of use of bundle of care in managing pressure ulcers. There was unanimous agreement that pressure ulcers bundle of care were much feasible, acceptable, convenient, and easy to execute and justify unlike where there is not guidance on what should the approach should be. In addition, bundle of care was associated with improved awareness on pressure ulcers, communication, collaborative care, patient participation, and support from the administration. All these are bound to improve the quality and safety of care delivered to the patients.

Practice Recommendations

In summary, the evidence from the literature supports the use of evidence-based practices in managing pressure ulcers. Using proven practices was associated in improved quality of care, saving on cost of care, increased staff and patient satisfaction, and reduced the risk of complications. The literature revealed diverse approaches either bundle or unitary practices that were associated with significant rate and effective healing of pressure ulcers. Most of the studies used in the review were quantitative studies, and despite the fact that one qualitative study was used, the level quality of evidence presented was convincing. There is consistency in the assessed articles reporting support for adoption of evidence based practices and practices that have been tested and approved for managing pressure ulcers. Therefore, considering the evidence gathered from the studies, this project recommends for a bundle of care that incorporates best practices in managing pressure ulcers. The bundles of care to be implemented with include 4 hourly patient-turning, pressure area care (application of oil and using soft beddings), negative pressure wound therapy, cleaning and dressing of the wound, nutritional support, and collaborative management. This bundle of care is the Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing (PUSH Tool) proposed by the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel.

Project Setting

The project setting describes the location where the project was implemented, which is more likely to be the hospital setting given the nature of the project. According to Proctor, Powell and McMillen (2013), understanding the project setting is crucial for effective project implementation. This understanding helps the implementers of the project to understand the resources available, the organizational culture, how the organization relate to the project, and the possible implications of the project to the project setting.

For this project, the setting was the Wound Care Office in Miami Lakes, in Florida USA. The office’s structure can be described as follows: it consists of a wound care specialist managing homebound patients with pressure ulcers. The clinic is a physician owned; thus, he is the main stakeholder of the project setting. The physician has two nurse practitioners who are involved in the day to day running of the clinic; thus, they also constitute the main stakeholders. The external stakeholders of this clinic include patients, the community, and other auxiliary entities such as suppliers and financers.

The typical clients of the clinic are homebound patients with a wide variety of ethnic and cultural backgrounds and health conditions. As already discussed in the PICOT question, the population of interest, which was targeted in this project setting were the patients suffering from pressures ulcers for stages III and IV. Thus, the targeted population can be viewed as one of the typical client groups of the clinic. The mission of the clinic, as established by the physician owner/director (2003), is to offer the highest level of care, wound healing and works together to design an individualized treatment program based on your medical history and the severity of the wound. The clinic’s vision is the improvement of the health of the community that it serves. Thus, a quality-improvement project like the one described by this report is in line with the mission and vision of the clinic.

The suitability of this project to the settings was established following a discussion with the owner and the staff of the clinic. In particular, the meeting uncovered the organizational need for improved pressure ulcer management and confirmed the organizational support for the project. Furthermore, the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Pressure Ulcers Scale for healing PUSH Tool 3.0 was approved as the intervention during the discussion because it provides excellent guidance that can be used to ensure that the clinic’s team implements best practices. One of the emerging factors in the discussion was that the clinic value delivery of quality care to the highest possible level. This project seeks to promote the quality of pressure ulcers management; thus, it aligns perfectly with the clinic needs.

Rusare and Jay (2015) assert the significance of the organization’s culture in determining the success of the project implementation. Organizational culture influences the sustainability of the project; thus, it is critical to assess the nature of the organization’s culture in relation to project management. The setting’s organization culture was found to be receptive to the project ideas, given the positive implications the project could have on the running of clinic. Furthermore, as can be noted from the clinic’s vision and mission, the promotion of the quality of care and the improvement of the provided services are some the primary values of the organization, which are shared by all the stakeholders. Similarly, the key stakeholders, including the nurses, highlight the fact that the clinic is always supportive of innovation. Therefore, the cultural specifics of the clinic proved to be conducive to change and supportive of quality improvement efforts. The described project corresponds to both these categories.

A strength, weakness, opportunities, and threat (SWOT) analysis identifies main strengths of the project setting as staff support, ability to align project to clinic schedules, improving quality of care, and minimal disruptions to setting. Noted weaknesses include inadequate knowledge of the community culture, shortage of staff, and unavailability of clinic pressure ulcer management tools. The project setting present potential opportunities such as improve delivery of care, improve pressure ulcers patients’ recovery, enhance good relations with community, and enhance proper use of resources. Three key threats were noted, which may impede the full success of the project unless these threats were undressed first. The threats include loss patients’ turnout, inadequacy of resources to implement the project, and significant level of communication barrier due to cultural diversity (see Appendix B). It is noteworthy that the identification of threats and weaknesses is a step towards their management, which can be carried out with the help of the strengths and opportunities. For example, during the project, the strength of the alignment of schedules was employed to manage the problem of staff shortage and resources inadequacy, which facilitated the project’s implementation.

The management of the above-mentioned SWOT elements was also employed to prepare the sustainability considerations of the project. All the identified strengths were viewed as facilitators; for instance, the staff support was considered to be one of the main factors that promised a sustainable change. The tools and models that were chosen for the project were also regarded as facilitators since they provided structure and valid instruments to the change. As a result, for example, the PUSH tool is a factor that has been expected to make the change sustainable due to its credibility, ease of use, and other positive qualities. It is noteworthy that the outcomes which have been achieved by the project can also be viewed as a motivational factor that promises sustainability to the change through the demonstration of its effectiveness (Pollack & Pollack, 2014; Small et al., 2016; Spear, 2016). Overall, the sustainability of the project is supported by multiple facilitators.

Some barriers were also determined, and they are described by the SWOT analysis as weaknesses and threats that can be managed accordingly. For example, resource shortage (including human resources) was resolved through careful management, and the cultural barriers were brought down with the help of communication and training. It is noteworthy that the problem of change resistance, which is rather typical for innovative efforts (Hanrahan et al., 2015; Laker et al., 2014), was almost non-existent during the project. All the minor resistance issues that were encountered were also easily resolved by determining their possible causes and reasons (most often, training-related concerns) and addressing them individually. In summary, the barriers to the change were present, but they were reviewed and brought down accordingly, which improved the sustainability of the project’s innovation.

Project Vision, Mission, and Objectives

According to Perera and Peiro (2012), a project should have clear set vision, mission, values, and objectives, which are critical in defining the significance, feasibility and sustainability of the project. The vision statement describes the future image of the project setting after the implementation of the transformative intervention (Perera & Peiro, 2012). The vision serves the role of inspiring stakeholders and motivating them to be part of the transformative agenda. The project mission statement, on the other hand, denotes the primary aim and reason for the project’s existence (Shahmehr, Safari, Jamshidi & Yaghoobi, 2014). The mission statement should pinpoint the project key purpose, targeted clients, distinctive attributes, jurisdiction/coverage, and mode of operation (Perera & Peiro, 2012; p. 751). The objectives dictate the targets the project seeks to achieve; thus, they act as the benchmark for assessing the success of the project together with the project projected outcomes.

For this project; the vision statement is to be the preferred practice of choice in effective management of pressure ulcers by implementation of evidence-based practice guidelines.

The mission statement reads to provide cost effective, quality, safe and high level wound care for homebound patients with pressure ulcers.

The main objectives include the following:

- To reduce occurrence of pressure ulcers by 10% among homebound patients attended to by Wound Healing Clinic in Miami Lake within a period of 8 weeks.

- To reduce spread of existent pressure ulcers among homebound patients to a maximum of 5% after the 8-week program

- To establish a justifiable wound care protocol based on evidence-based models, which maintain the reduction in spread and occurrence of pressure ulcers described in the other two objectives.

The risks of the project are minimal: the intervention is evidence-based, which implies that no negative outcomes are expected from it, and the educational intervention is not correlated with risks. The participation will be only voluntary and informed, which further limits potential risks. The only possible adverse outcomes are inefficient pressure ulcer healing, but it is an unlikely outcome, which is going to be prevented by using an evidence-based intervention and extensive training.

Project Description

In this section, I will describe the practice change that was carried out as a part of the project; it involved the adoption of a preventive and management approach aimed at reducing pressure sore incidence and complications. The practice change consisted of an educational/coaching program (Educational Component and Clinical Implementation) intervention utilizing the Pieper Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Test survey and the PUSH tool (Appendices C & D) for the staff who cares for patients susceptible to pressure ulcers. The program included instruction and coaching on proper diet, adherence to prescribed medication regimen, proper surfaced area, and how to get family involved. I had a core group of staff nurses trained on adequate knowledge on the management of pressure ulcers within the home setting, including training on how to maintain patient adherence.

My plan for implementation followed a recognized change model as a guide to enhance the feasibility and sustainability of the described practice change (Nilsen, 2015); thus, I’ve chosen the Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice (2017). My selection of the model was based on the fact that nurses have reported it to be intuitive and comprehensive; moreover, it has been used in significant number of academic settings, including many health care organizations (White & Spruce, 2015). The Iowa Model traces its origin back to the early 1990s and was established by a group of nursing research committee from University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics (White & Spruce, 2015). The model underwent considerable revisions and improvement and was later published on 2001 (Brown, 2014). The model has substantial support towards guiding clinical decisions and evidence-based practice implementation. The model’s application in multiple clinical and academic settings provides the researcher with comparative standards to guide the current project. The Iowa Model integrates research utilization with quality improvement in a relatively easy to understand algorithm (Schaffer, Sandau & Diedrick, 2013). The model postulates the ‘trigger’ concept, where external knowledge or a clinical problem are identified as antecedents for an EBP project (Nilsen, 2015). In implementation of the project, the process followed the ten steps adapted from the Iowa Model. Most barriers and facilitators have already been discussed as a part of the SWOT and sustainability analysis, but some of them will also be considered as a part of their respective change aspects and stages.

Problem Identification

In this step, I identified the problem that I intended to address in my project. In this process of identification, I considered evidence based practice and a number of factors. As a first factor, my chosen topic had to reflect priority standards based on the magnitude of the problem that was to be addressed (Doody & Owen, 2011). Pressure ulcers in homebound patients is a priority issue given enormous health, financial, social, and family burden that the problem causes to the patient as well as the economic burden to institutions and government. The second factor considered in topic identification is contribution to practice (Doody & Owen, 2011) and there is no doubt the project will draw significant contributions towards improving the quality of care. The third factor is the data and evidence availability, which for the purpose of this project is not a problem given the statistics of patients in USA and in Miami seeking pressure ulcers care. Lastly, I considered staff commitment and a multidisciplinary approach (White & Spuce, 2015), which can be viewed as project facilitators; this is an area where the clinic’s staff stakeholders in my setting have demonstrated excellent performance.

Formulating a Plan

Once the topic had been identified, a preliminary plan on the way forwards was established in consideration with the relevance to the organization. The plan was meant to ensure that the implementation process follows a framework or process, which can be easily monitored and evaluated.

Team Formation

The implementation process, as in any other major project is expected to be guided by a team, whose members understand both the organization and the innovative practice. According to Doody and Owen (2011), it is this team that is responsible for the development, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of the project. White and Spuce (2015) propose that the team should incorporate representative of major stakeholders or those to be affected by the described project. Such inclusivity is critical for reducing resistance to change, which is a major barrier to be brought down, and ensuring that all stakeholder groups are part and parcel of the change process. For this project, the team was comprised of the owner-physician, the staff nurses, the researcher, a representative from donors/financiers, social worker to represent the community, and myself as project leader. I have been working in long term care for the last 15 years in different positions, ranging from Nursing Assistant (CNA) to Director of Nursing for the last 4 years. Although I enjoy my current role in management, I remain especially devoted to the Wound Care area. I currently work for Wound Care technology as ARNP Wound Care specialist to direct and deliver advance wound care assessment and management. I consider that my leadership qualities and skills qualify me in this role and can be viewed as project facilitators. I used my experience and devotion to this topic to ensure the successful completion of the project.

The team began its work by drawing policies, procedures, and guidelines that were relevant to evidence-based practice implementation. Education was provided by power-point presentations to the staff nurses. As observed by Doody and Owen (2011), teams may encounter notable challenges such as role conflicts, inadequate resources, increased workload, inadequate knowledge on EBP, and conflicting opinions during deliberations. During the project, the mentioned barriers were rarely encountered due to the team’s motivation, prior experience of working together, and the promotion of collaboration and feedback. Any problems were addressed spot-on to avoid propagation of these errors to complicated levels.

Literature Appraisal

Step four entailed retrieving evidence and data from the literature and project setting. The selected team members from the previous step organized a brainstorming session to identify the main relevant sources of data (Doody & Owen, 2011). The literature appraisal used the process described above under “Articles Search Strategy” heading. Extensive documentation of the literature appraisal for my project is included in the PICOT Question and the Theoretical Framework research documentation which is provided above and in Appendix A.

Critique and synthesis the data

To ensure that the collected data was of high quality, the articles sourced from the databases should be graded. This project employed the Rapid Critical Appraisal Checklists, as well as ensured the articles were from credible authors. The implementation team was supposed to determine whether to use qualitative or quantitative data or both, and the latter approach was chosen.

Testing the data for reliability and validity

Reliability and validity of the data collected were established by assessing the methodology employed by the studies. The data was assessed for effectiveness, appropriateness, and feasibility to determine the reliability and validity of the data collected.

Pilot Change

In general, this step of the Iowa Model entails pre-testing the results of the proposed evidence-based practice in a setting other than where this project was conducted. This ensures that the feasibility of the proposed evidence-based practice was assessed and ascertained before rolling out the project. Pilot testing is crucial since it enables the implementation team to address some of the emerging challenges that could have been unnoticed in theoretical approach. Thus, for the purposes of the IOWA Model, the DNP project represented the pilot change or program change. As prescribed by the model, this 8-week implementation and intervention was used to identify the efficacy of the change in the care of pressure ulcers.

Implementation

The study was implemented in two main phases, the Educational Component phase and the Clinical Implementation phase. The Educational phase consisted on an educational/training workshop of the staff nurses or “participants” on the use of the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Pressure Ulcers Scale for Healing PUSH Tool 3.0. These guidelines include the EBP standards, consider the strength of the evidence, and the appropriateness of the setting. This stage of the program also included initial instruction and coaching; specifically, proper diet, adherence to prescribed medication regimen, proper surfaced area, and how to get family involved. I had a core group of staff nurses trained on adequate knowledge on the management of pressure ulcers within at-home setting, including training to nurses on how promote patient adherence. This bundle of care refers to the pressure ulcers PUSH tool 3.0 proposed by the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. As the subject expert, I imparted the education/instruction/coaching part of the implementation.

I used Power-Point for the classroom presentations with question and answers sections to address issues raised by the participant staff nurses. The hand-on training used actual patients, or staff nurses to perform the physical demonstrations with the assistance of staff team members. Besides education/instruction, I used daily coaching, as necessary to ensure that the practicing nurses are learning and applying the new guidelines. The coaching included daily checking to ensure adherence to the guidance and instructions for proper care. I also provided hands-on training specific to the wound care program. At the end of the training session(s), I conducted competency evaluation to score each staff nurse on their achievement, which consists on a pre-assessment of knowledge using the Pieper Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Test (Appendix D).

The second stage, or the clinical implementation phase, consisted on the actual implementation of the new guidelines during an 8-week intervention program. This stage of implementation included execution of the plan, tracking wound condition, and the collection of care data for later use in assessing the efficacy of the implemented changes in the care of pressure ulcers. The plan was executed with the expectation of getting the anticipated results, significant reduction in the occurrence of pressure ulcers and faster healing when these occur, i.e. effectiveness with respect to wound care. This project involved implementing an evidence-based practice project as proposed in the recommendation section. Possible barriers to implementation of the project such as inadequate resources, resistance to change, inadequate time, and communication barriers were addressed in advance using appropriate measures as deemed fit by the implementing team.

Resources

I used the human resources available at the clinic for this project: the two nurse practitioners, the physician owner and the staff nurses; moreover, I served as a facilitator to resolve conflicts and address barriers on a timely fashion. All staff nurses who participated in the educational/training workshop were given the opportunity to elect or decline to participate in the DNP project component. The nursing staff who elected to participate on the project were provided an informational letter about the purpose of the project, and they were given the opportunity to ask questions before any study procedures were initiated. Two of the most recent subject de-identifiable data from each selected nursing staff was selected for this project, for a total of twenty (20) randomly selected subjects. The subject information will be maintained in a study database for the duration of this study, and all data will be maintained by the project leader for seven years.

In addition, persons living with homebound patients acted as ancillaries through recording of data needed for the project. Research data was sourced from nursing and medical journals available to the researcher and those offered through the university. Additionally, relevant data available at the clinic forms an integral part of the project. The researcher used personal finances, contribution from friends and family, and institutional budget support. The total budget is illustrated in the Appendix E.

Monitoring and Evaluation

Monitoring and evaluation is a critical practice that enhances appropriate deployment of available resources to deliver the desired outcome. Monitoring entails a systematic and continuous assessment of the ongoing project to assess the actual implementation process against the propose approach to determine whether the set standard is met. Evaluation on the other hand, entails assessing the project on completion of set stages and at the end of the project to determine whether the projected outcomes are achieved. These two stages were crucial towards informing on how to improve the practice. The described project employed its formative and summative evaluation methods to follow these elements of the model.

Dissemination

The stage entails the sharing of the project findings with the relevant stakeholders. For this project, the findings will be disseminated through publication in a credible journal targeting those training on pressure ulcer care, those taking care of pressure ulcer patients, and those in policy making docket regarding pressure ulcers prevention and management. In addition, the results will also be made available in the clinic website with the permission of the clinic management. Also, the patients involved in the project was provided with the findings as a gesture of recognizing their role in the project.

Cost of Implementation

The cost of implementation is considered minor. It includes both direct and indirect expenses. In the direct category, I included salaries and benefits, supplies, services, and the work of the statistician. As part of the indirect cost, I only envisioned overhead. I used personal finances, contribution from friends and family, and institutional budget support to cover these costs. The total budget is illustrated in the Appendix E.

Project Schedule

A project schedule that covers the entire project in included as Appendix F. The schedule addressed the timeframe for the completion of the two main study phases, the educational component and the clinical implementation, keeping in mind that this project needed to be achievable within my last two practicum courses. The timeframe of the project did not allow monitoring long-term outcomes, which might be viewed as a constraint or barrier, but as a pretest-posttest pilot change, the project could be limited to short-term results. Therefore, the timeframe can be viewed as appropriate.

Project Evaluation Results

Evaluation of the project is critical for determining the areas that should be reinforced in subsequent projects or full implementation employing the chosen practice, beyond the 8-week project duration. In evaluation, the achieved standards and outcomes are compared with the projected outcomes for purposes of determining any existing disparities and reasons behind these differences (Schaffer, Sandau & Diedrick 2013).

The evaluation plan for the described DNP project can be subdivided in two stages. First, I evaluated the nurses’ knowledge before and after the education/training/coaching sessions. Then, the evaluation focused on the tracking of wound care data for the duration of the project (8 weeks) and on the outcomes of the intervention. The expected outcomes for this project included improved rate of pressure ulcers healing, reduced rate of pressure sores recurrence, reduced cost of pressure ulcers care, and in general improved quality of life for the target population. Therefore, the resulting data collected from the project participants was assessed against the baseline data and the estimated levels of outcome attainment to determine the effectiveness of the project. Both formative and summative criteria were employed to evaluate the performance of the project.

Participants and Human Subject Protection

The study project included a team of twelve (12) nursing staff or “participants” who elected to participate on the study by responding to the recruitment letters. Participants received a Participant’s Study Identification Number (Participant’s ID) which consisted of a participant’s favorite color followed by a chronological three-digit code. Participants completed a Pre-and-Post Pieper Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Test Questionnaire, and information obtained from these questionnaires were stored for future publications. The data to be considered for evaluation was gathered by the participants from the recruited study subjects.

Those included as study subjects were patients with stage III and IV pressure ulcers. They were both male and female, aged above 18 years, of all races. The participants selected one or two most recent patients diagnosed with stage III or IV pressure ulcers for the project, for a total of twenty (20) study subjects. Nursing staff selected the subjects depending on the inclusion criteria and their consent. The study subject’s privacy and security were maintained at all times, and the data will be kept confidential in the future as well. A unique Subject Identification Number (Subject ID) was used, which consisted of the first three letters of the subject’s favorite color followed by a three-digit code. The consent of all the participants and subjects was obtained. The Chamberlain College of Nursing Institutional Review Board approved of the project’s proposal and its methods of protecting its subjects and participants.

Formative and Summative Evaluations

Formative evaluation was employed at different stages of the project implementation, as identified by the project implementation team. These stages were critical in defining the achievement and success of the project. With respect to the training/coaching of the staff nurses, the formative evaluation assessed the nurses’ knowledge/skills before and after the educational sessions; moreover, diagnostic questioning using the Pieper Pressure ulcer knowledge test (see Appendix D), was used during the baseline procedures of the educational component phase and at the end of the implementation phase, or week 8th. I used the feedback from this ongoing questioning to reinforce key points and address weaknesses in my training, including provision of more details on the patient’s needs, as well as specific tasks that nurses should perform to promote patient’s adherence. These formative assessment tools produced qualitative data, which was analyzed thematically.

With respect to the tracking of wound care data, a checklist was used to check items such as assessment of the skin surrounding a wound, tissue type (necrotic, slough, granulating), and signs of infection (see Appendix E). This formative evaluation was completed at the baseline procedure of the educational component phase, and was collected as part of the subject’s wound care assessment evaluations for the duration of the project (8 weeks). Correction measures were taken, as needed, to address deviations, inaccuracies, and other deficiencies that may be identified during these formative assessments.

The summative evaluation was done after the completion of the project having collected all the data. The summative evaluation included a systematic process for collecting and analyzing data. Since different outcomes were assessed from different measures, the type of data was not universal for all the outcomes. Some were ratio, ordinal, and interval in nature depending on the outcome under evaluation. The quantitative data were analyzed with the help of descriptive and inferential statistics. The latter involved the use of t-test for the pre- and post-intervention Pieper Pressure ulcer knowledge test data and chi-square test for the PUSH tool data, as well as variance, sequential, and decision analyses depending on the specifics of the data and the purpose of analysis (Polit & Beck, 2017).

For the summative evaluation, each nurse’s learning at the end of the 8-week period was assessed by comparing his or her competencies/skills/knowledge at the end of the program against his/her initial capabilities prior to the training and implementation. This part of the assessment was carried out with the help of the Pieper Pressure ulcer knowledge test (see Appendix D), which is a valid and reliable tool that produces ratio data (Pieper & Zulkowski, 2014). Moreover, the nurses expressed their perceptions and attitudes regarding the intervention with the help of the final section of the Survey Tool (see Appendix G). More importantly, the summative evaluation was applied to the effectiveness of the project in achieving its main goal. For the assessment of the latter outcomes, the principal tool was the PUSH tool (see Appendix C). This tool provides valid and reliable means of assessment of pressure ulcer characteristics and prediction of wound healing; it produces ratio data. The use of a wound healing measurement tool provides a means for quantifying outcomes (Cauble, 2010). Wound measurements were carried out by nurses in their routine practice. These measurements were able to identify whether healing took place; wounds that would not show decrease in size and other characteristics would be indicative of lack of healing and would need to be further evaluated. The evaluation of healing improvement at the end of the period was the key summative evaluation of the project.

Extraneous Variables

Extraneous variables are those factors that have significant impact on influencing the outcome or the trend of the dependent variable. These variables should be assessed, identified, and their impact limited. Otherwise, they may skew the results and obliviously lead to wrong outcomes, conclusion, and recommendations. The project team was tasked with the role of identifying extraneous variables for this stand and containing them. Probable extraneous variables included malnutrition; comorbidity such as diabetes, cancer, anemia, and clotting disorder which have a negative influence on wound healing; and poor compliance to the preferred pressure care management.

Regarding the first extraneous variable, a number of comorbidities proved to have an effect on wound healing time, including, for example, paraplegia. The prevalence of these conditions in the subjects is demonstrated in Figure 2. This extraneous variable was controlled by considering the clients with comorbidities that could influence the outcome of the project. It is noteworthy that the time required for Stage IV pressure ulcers to heal was greater than that needed for Stage III pressure ulcers to heal regardless of the comorbidities. Concerning the second anticipated extraneous variable, the results indicate that malnutrition did not lead to statistically significant differences in the healing time (S²= 4.23405) as can be seen in Table 1. As a result, this variable was not taken into account during the data analysis despite the fact that it affected almost a half of the patients (see Figure 3). Finally, the compliance issue, which was viewed as the third potential extraneous variable, was resolved by ensuring that the staff which executed the PUSH Tool read from the same script and by monitoring the participants. In summary, the project considered the possible extraneous variables and found a way to control them.

Results

The key results of the project are related to the process of pressure ulcer healing, knowledge acquisition by the participants, participants’ perceptions regarding the intervention, and the cost-effectiveness of the intervention. The process of ulcer healing is illustrated in Table 2. As can be seen from it, the pre-intervention ulcers had the average size of 147.51cm2 with 45% of the wounds (9 cases) being more than 24.0 cm2 in size. Also, 20% of the ulcers at that point were classified as producing a heavy amount of exudate, and 80% were of moderate exudate amount. Finally, three tissue types were present in the population at the beginning of week 1: 30% of the wounds had the necrotic tissue type, another 30% were classified as slough, and 40% exhibited granulation.

Throughout the project, these numbers decreased: by the middle of it (week 4), only 20% of the wounds demonstrated the size of over 24.0 cm2, and by week 8, only two ulcers were that large (10% of the total number, and 12.5% of the unhealed ulcers at that time). Week 6 involved the appearance of the first fully healed ulcer; on week 8, the total of five fully healed ulcers was achieved. The number of ulcers with heavy exudate was steadily decreasing, and by week 6, no ulcers produced heavy exudate. Also, by week 5, no necrotic tissue type was present in the sample.

By the end of the project (week 8), the average size of ulcers was reduced to 13.78cm2 (by 94.56%). Also, by week 8, no ulcers produced heavy exudate, only one ulcer produced moderate exudate, and a total of eleven ulcers produced no exudate. Moreover, by week 8, no necrotic tissue or slough was detected, and only nine (45%) of the wounds had granulation tissue. Five more wounds had the epithelial type of tissue, and the rest of the wounds were closed. Thus, the PUSH tool demonstrates that the intervention was rather effective in facilitating the healing process: 100% of the wounds were healing (changing in size, tissue type, and exudate). The specifics of the time required for the healing of the ulcers are presented in Figure 4.

The Pre-and Post Pieper Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Test was used to determine the knowledge of the participants on pressure ulcer management before and after the intervention. As can be seen in Figure 5, at the beginning of week 1 (when the pre-intervention test took place), only 8% of the nurses exhibited high-level knowledge of the matter. At the time, 50% of the nurses had a medium-level knowledge, and the rest (42%) had little knowledge of pressure ulcer management. After the intervention, no nurses exhibited low-level knowledge of the topic, and only 8% of them had a medium-level knowledge. 92% of the nurses exhibited high-level knowledge of pressure ulcer management after the educational intervention.

Therefore, all the nurses have improved their knowledge as a result of the intervention, and the majority of them obtained a high-level understanding of pressure ulcer management. Some of the areas of knowledge that were improved include assessment and staging of ulcers, identification of wound tissue, the use of supplies and materials, and the understanding of the effects of comorbidities. Also, the educational intervention improved the nurses’ ability to educate patients. Nurse training is a major contributor to the quality of care, and it can be viewed as a predictor of the successful use of the PUSH tool to the benefit of the patients.

The analysis of the participants’ feedback and the Survey Tool (see Appendix G) demonstrates that the participants viewed the intervention as helpful. 100% of the nurses perceived the intervention as a positive change and considered it to be more effective than the previously used approach. Regarding the motivation of the positive comments, the nurses have offered five key reasons that are presented in Figure 6. They include the faster healing of ulcers, decreased costs, the identification of comorbidities, and the introduction of proper offload and nutrition. In summary, the nurses approve of the change, which must contribute to its sustainability and the project’s success.

Finally, the cost-efficiency of the intervention was assessed by comparing the costs of the care that was performed with the intervention to the expected costs that were estimated with the help of the data describing the previously used approaches. As can be seen from Figure 7, the projected costs were almost twice as large as the actual ones tracked by the participants. The final costs for all subjects amounted to a little over $2,000 compared to the expected costs of $4000. Therefore, the intervention proved to be cost-efficient, which was one of the anticipated outcomes.

Discussion and Implications for Nursing and Healthcare

The results of the study indicate that PUSH is effective in the management of pressure ulcers and can contribute to and track the process of pressure ulcer healing while also improving the cost-efficiency of the treatment. Furthermore, the educational intervention of the project successfully improved the knowledge of the participants. Thus, both patients and nurses benefited from the project, which can be viewed as its primary micro-level impact. As a result, it can be suggested that the PICOT question has been answered in the following way: for Registered Nurses and assistive personnel making home care visits for Jose Victor Perez DO, Miami Lakes, FL, the education on and implementation of the evidence based Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing (PUSH Tool) tool, along with audit and feedback, has led to improved efficacy in the management and care of pressure ulcers over an eight-week period.

The internal validity of the study was ensured by controlling the extraneous variables (Polit & Beck, 2017), which are discussed above. Certain limitations of the study are explained by its design and purposes. The project was a pilot change, which is why it was carried out on a relatively small scale. The sample of the project is not very large, and the time constraints prevented it from collecting the information on any long-term outcomes. Also, as a pretest-posttest study, the project did not compare the healing rates correlated with PUSH to the rates relevant for other interventions. The only direct comparison offered by the results was connected to cost efficiency.

Moreover, there are limitations that are connected to potential concerns. The possibility of measurement imprecisions cannot be completely ruled out, although the nurses were instructed to re-check their measurements. Regarding the sources of bias, the quantitative tools used by the study did not leave room for them; in fact, the use of valid and reliable tools is a major strength of the study (Choi, Chin, Wan & Lam, 2016; Pieper & Zulkowski, 2014). However, the qualitative data might have been affected by the nurses’ bias (Burns, Grove, & Gray, 2015). All the mentioned limitations need to be taken into account when considering the implications of the project.

The described project was a pilot change (Iowa Model Collaborative, 2017), which means that its implications for the meso-system of the organization need to be reviewed from the perspective of the preparation to the future change. The results of the project indicate that the intervention has led to an increase of the knowledge of ulcer management in 100% of the participants while also resulting in a notable decrease in pressure ulcers’ size, exudate, and severity, as well as an almost 50% reduction of the cost of care. Therefore, the pilot test can be viewed as a success, which means that the primary recommendation of the project consists of proceeding with the change within the organization. The step might involve the development of a new similar study that would take into account the major limitations of the current one (small sample size and the absence of long-term outcomes and comparisons) and avoid them.

Regarding the more global implications of the study, its major conclusion about the effectiveness of the PUSH tool can be of interest to the healthcare community. Moreover, some of its findings may be of interest from the point of view of change implementation and EBP. Finally, it can be suggested that the study contributes some data to the relatively understudied topic of pressure ulcer management (Murray, Noonan, Quigley, & Curley, 2013; Sullivan & Schoelles, 2013). These implications are relevant from the macro-level perspective.

Plans for Dissemination

The results were disseminated to different platforms where they could be accessed by the targeted audience. Dissemination is significant in any project since it enhances the capability of the audience to use the project data to inform practice, research, and policies. The results were shared with the clinic to inform future pressure ulcers care practices. This presentation of the findings to the institution was done during a staff meeting. The response of the stakeholders was positive, and the findings of the study will be used to support future changes and ensure their sustainability. The results were also presented to the university research committee, the ethical committee, and other invited members to evaluate, appraise, and offer the way forward with the results. Since the findings are positive, they will be prepared to be presented to policy makers in the health care sector to offer guidance for improved pressure sores management practices. The final copy of the project will be prepared and printed into a booklet.

The project findings are expected to have significant implications for pressure sore management. Therefore, the results may also be disseminated to the professional community. This step will be achieved by publishing the findings in a credible health care journal such as the SAGE Journal, International Journal of Evidence-Based Practice, or the Association of perioperative Registered Nurses. These journals are selected for their credibility and reputation. Publishing the results in these journals will increase accessibility of the findings across the world; hence, increasing the usefulness of the findings to extensive jurisdiction. The results may be employed to revising the existing practice or elicit further research interest that will improve the quality of the practice on pressure injuries management.

Summary and Conclusion

As intended, the present paper has reviewed a pretest-posttest pilot change DNP project that focused on evaluating the impact of using evidence-based practice PUSH Tool on the healing process of pressure ulcers among homebound patients, specifically patients with stages III and IV pressure sores. Evidence-based practice is redefining the nursing practice with significant interest being placed on the vitality of adopting the best practice in addressing patients’ need. As much as there has been considerable research on pressure ulcers management, little evidence exists on how using EBP can benefit those patients receiving their care at their homes. The presented project has attempted to contribute to this relatively understudied field.

The project’s setting was in wound care clinic based in Miami, Florida in USA. The reviewed literature demonstrated strong link between the use of EBP in managing pressure ulcers. Some of the factors that were considered in the evidence-based practices implemented and advocated by the eleven articles reviewed captured importance of improving patient nutrition, reducing pressure, reducing bacterial exposure to the ulcers, ensuring effective wound cleaning and dressing, and pain management. These aspects form a bundle of practice that should be considered in managing pressure ulcers. The project was feasible and within manageable budget. Using Iowa Model, the implementation of the project was more enhanced and possible given that the model has proven utilization in guiding evidence based practice. The results of the project indicate that the intervention was successful in improving the knowledge of pressure ulcer management in the participants, reducing the cost of care, and managing the healing process. As a result, the PICOT question was answered, and it was determined that the intervention could have a positive impact on pressure ulcer management within the settings. The primary implication of the project is that the intervention is appropriate for the clinic. Therefore, the project has performed its function as a pilot change, and the clinic can be recommended to proceed to implement it on a more comprehensive scale. The dissemination plans include the presentation of the findings to the clinic and the Chamberlain College of Nursing. The results of the project have been obtained a very pivotal period for pressure ulcers care. This is in connection to the increased attention to have the rates and effects of pressure ulcers reduced to cut down on the cost of care resulting from preventable conditions and improve the quality of life for the target population.

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (2014). Preventing pressure ulcers in hospitals: are we ready for this change. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Web