Introduction

There are many ways to advance the knowledge about intestinal disorders in people of different ages, and communication among different healthcare professionals and researchers remains one of the most effective methods. Clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of colon cancer were developed by the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons in 2017. A disease of the Colon and Rectum is a well-known journal developed by the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS) where specific practice parameters for physicians and medical care workers for caring for patients with the already identified disease are introduced (American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons 2018). In the chosen practice guidelines, the experts in the colon and rectal surgery share the standards of high-quality patient care to describe, prevent, and manage treatment for colon cancer (Vogel, Eskicioglu, Weiser, Feingold, & Steele, 2017). The aim of this critical appraisal is to evaluate the quality of the ASCRS clinical practice guidelines, investigate its methodological strategy, and clarify if there are any additional recommendations to improve the current state of affairs and health care that should be offered to patients with colon cancer or other associated rectal problems.

Domain Table

Comments

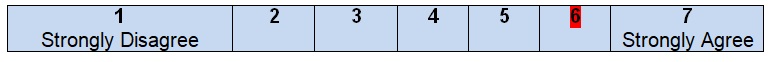

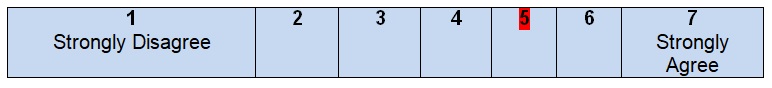

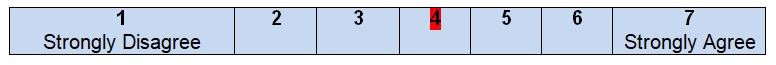

The authors of the guidelines begin their project with a clearly identified statement of the problem and the goals that have to be achieved in any healthcare setting. Colorectal or colon cancer is a common malignancy that introduces a serious health problem for patients of both genders and of any age (Siegel et al., 2017). It is the third leading cause of cancer death in the United States (Siegel, Miller, & Jemal, 2017). Therefore, practice guidelines should address this issue and evaluate treatment options for patients who are diagnosed with colon cancer. The purpose is to provide information on the decisions to be made for caring patients but not just give some specific forms of treatment and make users follow recommendations without a possibility to deviate rules in regards to a specific situation. The inclusive nature of the guidelines enlarges the possible audience and promotes a wider scope of colon cancer treatment.

The health question(s) covered by the guideline is (are) specifically described

Comments

It is hard to agree with the fact that all health questions or at least one question are covered by the guidelines. The authors do not find it necessary to pose questions in order to describe the scope of the guideline or develop an effective search strategy. The user of the guideline is not able to compare his/her questions with the questions that the authors want to answer. An overall purpose of the guideline is to describe colon cancer and give recommendations for healthcare experts who have to work with patients, including the assessment of the condition, available resources, and stages of treatment that usually depend on antigen levels (Becerra et al., 2016). Due to the absence of health research questions in this piece of work, it is impossible to predict its outcomes, evaluate the quality of the work done, or even understand the patients’ needs in the context determined by the guideline.

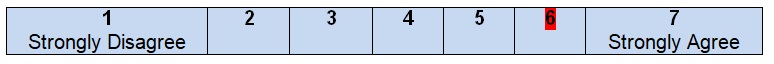

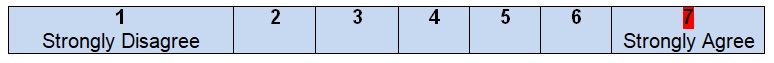

The population (patients, public, etc.) to whom the guideline is meant to apply is specifically described

Comments

After looking through the introductory paragraphs of the guideline, the reader can easily understand that the information given can be applied to a specific group of patients who have been diagnosed with colon cancer and require additional treatment to be organized. It is stated that colon cancer can be the reason for death in patients of both genders; hence, American women and men who have the disease can be defined as the potential audience for the guideline. Colon cancer is not a final sentence for people who believe that they have to stop trying various therapies and searching for solutions. These guidelines introduce an approach with clearly defined steps, options, and descriptions at different stages. From the point of view of the population to whom this plan of work can be applied, the authors meet all the necessary criteria and give brief but clear recommendations.

Domain 2. Stakeholder Involvement

The guideline development group includes individuals from all relevant professional groups

Comments

The work of the Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons turns out to be the basis for the development of the guidelines under discussion. Some information about the members of the development group can be found in the guidelines, including the names of the authors and their degrees. All of them were identified as specialists with a Doctor of Medicine degree. Although it is clear that the authors are members of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, no information about their geographical location is given in the guidelines, and it is necessary to surf the web in order to understand that this organization is located in Oakbrook Terrace, Illinois (American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, n.d.). At the same time, correspondence with healthcare experts is identified as one of the sources for the development of the guidelines. Scott Steel is recognized as one of the members of the development group. He is a professor of Surgery at the Case Western Reserve University and a chairman at the Department of Colorectal Surgery in Cleveland Clinic.

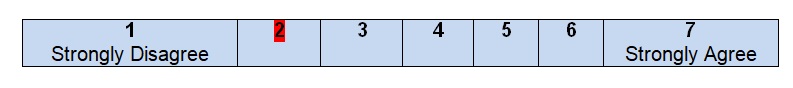

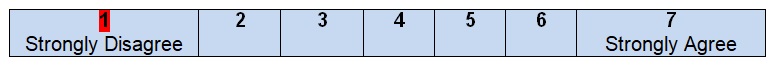

The views and preferences of the target population (patients, public, etc.) have been sought

Comments

Although some facts about the target population are mentioned in the guidelines under analysis, it is still hard to find enough information about patients’ experiences and expectations of health care and recommendations’ development. There are no discussions of formal consultations with patients and interviews during which it is possible to obtain data about people’s values and preferences. In other words, in these guidelines, target population perspectives are poorly presented and evaluated. This approach can be explained by the composition of the development group and the intentions of the authors to focus on treatment and evaluation of the condition, including the use of the existing preoperative laboratory tests or specially developed systems in terms of which patients share their private information (Guyatt et al., 2006). The most frequent source of information about patients includes the results of randomized controlled trials that were developed during the last ten years (Ng et al., 2012; Park, Choi, Park, Kim, & Ryuk, 2012). Still, the lack of direct communication with patients prevents giving high rates for this part of work.

The target users of the guideline are clearly defined

Comments

The distinctive feature of the chosen clinical practice guidelines is special attention to its expected target audience. First, the authors state that this project defines the quality of care by using international efforts, meaning that this guideline can be an effective tool for people from different parts of the world. Second, it is specified that these guidelines may be used by all practitioners and health care workers in order to understand the basics of the treatment of colon cancer. Finally, patients who want to obtain enough information about the management of their disease whether it is localized, regional, or metastatic can use this paper and improve their knowledge and decision-making (Murphy et al., 2017). Regardless of the level of knowledge of the target population, the guidelines contain enough clear information and recommendations to promote effective colon cancer care.

Domain 3. Rigour of Development

Systematic methods were used to search for evidence

Comments

There is a separate section with the description of a search strategy that was used for the creation of the practice guidelines for colon cancer. Three databases, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Database of Collected Reviews, were chosen for systematic reviews. It was also mentioned that the previous parameters developed by the American Society of Colon & Rectal Surgeons were used as the basis. The period is also clearly indicated: from January 1, 1997, to April 21, 2017, with a complete search strategy being included as an appendix to the guidelines. Journal and articles were searched according to the text words and key terms that were associated with colon cancer and patients’ problems. This particular item of the guidelines is well written and contains all the necessary descriptions and explanations. After reading the section, no additional questions about the search strategy appear, and the reader can get an idea of how the information was gathered and analyzed.

The criteria for selecting the evidence are clearly described

Comments

The authors identify including and excluding evidence by the search in their project. In total, the number of sources used for analysis was 16,925 journal titles (Vogel et al., 2017). Then, some sources were excluded because of their irrelevance or because of being outdated. The assessment of the material was made to meet the inclusion criteria (full-text articles and available abstracts). Target population characteristics included patients with colon cancer being diagnosed in clinical settings. The development group made a decision to work with observational and retrospective studies such as meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and practice guidelines (Kahi et al., 2016; Rahbari et al., 2012). The grades of recommendation, assessment, development, and evaluation (GRADE) system was introduced to identify the level of evidence for a single recommendation in the guidelines (Vogel et al., 2017). The outcomes depend on the results of each study that was chosen for specifically divided recommendations.

The strengths and limitations of the body of evidence are clearly described

Comments

In the chosen guidelines, the GRADE system can be used as a basis for the analysis of statements that can highlight the strengths and limitations of the evidence. All the sources used for the creation of the guidelines are introduced in a table format. For example, there are sources with strong recommendations and high-quality or moderate-quality evidence with their strengths to outweigh risks and limitations because of inconsistent results (Godhi, Varshney, Saluja, & Mishra, 2015; Ullah et al., 2015). Some recommendations were based on the sources with weak (low-quality) evidence where observational studies and cases contained ineffective or unnecessary treatment approaches (Engelmann et al., 2013; Parnaby et al., 2012). This description of how the body of evidence has to be evaluated for bias, including the recognition of study designs, methodologies, results, and benefits, is enough to promote the successful development of the guidelines. All data is well-written in the project with a possibility for the reader to understand the chosen background and the required preparations.

The methods for formulating the recommendations are clearly described

Comments

The examination of the introductory paragraphs where the guideline development process is described proves that the authors formulate their recommendations using clearly defined methods and approaches. There is an appendix with a search strategy and a GRADE system table that help to understand the main steps of the members of the development group. The GRADE technique evaluates the benefits and risks of recommendations and analyzes the quality of the studies’ methodologies and implications. When the results of the GRADE technique seemed to be incomplete, the consensus from the committee chair and three more participants could determine the outcome. The results of the recommendations and outcomes were determined by the committee members, as well as the offered Grade system, but the authors did not specify how exactly the processes influenced recommendations.

The health benefits, side effects, and risks have been considered in formulating recommendations

Comments

In formulating the recommendations for patients and healthcare professionals for treating colon cancer, the authors succeed in discussing the health benefits, side effects, and risks. For example, management of stage IV colon cancer disease, neo-adjuvant approaches to chemotherapy is recommended before resection (Vogel et al., 2017). Five-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) were chosen for consideration with the promotion of such benefits as downsizing during resection and disease-free survival during a post-operative (Nordlinger et al., 2008). The risks and benefits of resection of a tumor are properly discussed in the guidelines by using past observational studies and retrospective analyses and underlying the decrease in survival when incurable metastases are observed (Yun et al., 2014). The balance between benefits and harms or risks of various treatment approaches is discussed with strong recommendations regarding existing documentation and prognostic information in patients with different stages of colon cancer. However, because of no separate section with benefits, risks, and harms of cancer management in the guidelines, the reader fails to find the necessary information quickly.

There is an explicit link between the recommendations and the supporting evidence

Comments

In the guidelines, there is an explicit link between recommendations and evidence. The project is divided into several sections, depending on the goals for healthcare practitioners being achieved. First, the description of the recommendation is given, then, several supporting pieces of evidence from different studies are added to make sure that each solution, approach, or theory has a specific background. Each recommendation is properly linked to key evidence that is properly indicated in the reference list. For example, when patients have tumor-related emergencies such as bleeding or perforation, the goals of treatment include averting serious complications like sepsis or death, control of the tumor’s development, and timely recovery (Hogan et al., 2015). To approve the chosen CT angiography and colonoscopy, several studies were analyzed where the bleeding was observed in 40% to 90% of patients and stopped with the help of angiographic embolization in 70%-90% cases (Koh et al., 2009). All this information can serve as a good example of how to use evidence and support new recommendations.

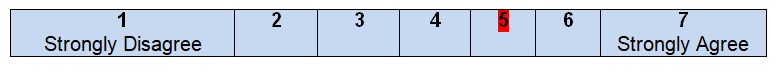

The guideline has been externally reviewed by experts prior to its publication

Comments

In the guidelines, the authors underline the necessity to review the developed projects several times. First, the committee chair, vice-chair, and two assigned reviewers were assigned to determine the outcome (Vogel et al., 2017). They were not the direct members of the development group. The second review was organized by the members of the ASCRC, but their participation cannot be applied to this particular section because they were working in the joint production of the guidelines all the time. Finally, the Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee was the body to approve the guidelines. However, the fact remains unclear as the names of the members were not mentioned, and it is hard to understand which reviewers were the members of the development group, and which reviewers were not interested but professionally prepared practitioners. The role of the representative of the Department of Colorectal Surgery, Steele, has to be mentioned as this professor directly participated in the development of recommendations. In general, it is correct to admit that the guidelines were externally reviewed before the publication.

A procedure for updating the guideline is provided

Comments

It is stated that the review of the guidelines for the treatment of colon cancer has to be updated every five years. According to the given criteria for this rubric, the authors of the guidelines met the necessary requirements. First, they used the statement that the guideline had to be updated (Vogel et al., 2017). Second, the explicit time interval in five years was identified to promote effective decision-making (Vogel et al., 2017). As for the third point, the methodology of the updating procedure, the authors did not give any specific recommendations or decisions. It could be guessed that the guidelines have to undergo the same review procedures and include the evaluation of recent studies. Still, no clear information can be found on the last point, and it is impossible to give the highest rating for the performance of this task in the appraisal.

Domain 4. Clarity of Presentation

The recommendations are specific and unambiguous

Comments

The general look of recommendations is clear and properly organized. There are several important headings and subheadings to guide the reader. There is a statement of each recommended action, e.g., preoperative radiologic staging or positron emission tomography to identify the stage of colon cancer. The purposes and population of the recommendation actions are also clearly described. However, some sections do not contain several options, and it seems to be weird when one statement like the management of locoregional recurrence has only one recommendation that is using a multidisciplinary approach. The same shortage can be observed in the section with the recommendations regarding documentation. The authors use one heading to explain that diagnostic workup, intraoperative findings, and some technical details are necessary to create the operative report instead of clearing up each requirement under a separate heading (Vogel et al., 2017). In some cases, the information seems ambiguous when the authors identify sentinel lymph node mapping as a part of the tumor surgery treatment plan but define it as not effective enough to replace lymphadenectomy.

The different options for management of the condition or health issue are clearly presented

Comments

The peculiar feature of the guidelines under consideration is the presentation of various options for the treatment and control of colon cancer in patients of both genders. The authors underline that evaluation and risk assessment of disease-specific symptoms and past medical history cannot be ignored by healthcare providers. The assessment can be developed before giving the final diagnosis as well as during the treatment process to evaluate the lesion and its progress (Vogel et al., 2017). Surgical treatment is defined as the most effective and necessary step after tomography is applied to prove the diagnosis. Resection, extended lymphadenectomy, and mapping can be chosen regarding the sensitivity of sentinel lymph nodes in patients. This description of options and the identification of specific clinical situations turn out to be appropriate contributions to the achievement of set goals.

Key recommendations are easily identifiable

Comments

The description of recommendations has a properly visual organization with typed in bold headings, as well as different colors being used. There are also several tables to explain the categories of colon cancer with the necessary definitions and the GRADE rubric that shows the benefits and shortages of recommendations. It is easy to combine the information while reading the guidelines and develop personal interpretations of the findings for each recommendation. Specific guidelines are grouped in regards to the purposes set by the authors. However, the only shortage in the chosen style of presentation is the length of paragraphs. Sometimes, it is hard to read long sections and underline the essence of the message. Therefore, in general, it is possible to strongly agree with the fact that key recommendations are easily identifiable, but the length of the paragraphs can be improved during the next update. Still, this suggestion is not essential as per the criteria of the chosen section.

Domain 5. Applicability

The guideline describes facilitators and barriers to its applications

Comments

It is important to examine if the guidelines describe facilitators and barriers to recommendations’ application because they determine the way of how the reader is either a healthcare provider or a patient. In the chosen guidelines, the authors do not develop a separate section with the necessary concepts being identified. Once, it was mentioned that various diagnostic tools like tomography or MRI scan can facilitate the process of the identification of the adjacent organ (Vogel et al., 2017). This information is not enough to identify all barriers and facilitators in respect to colon cancer as the chosen health problem. The description of various diagnostic tools has strong evidence and evaluation. There is no explanation if local hospitals should have all of them or only a part can be enough to manage colon cancer control. The information gathered on the topic influenced the guideline development process along with the formation of recommendations. However, it seems that the section with barriers and facilitators to its application is totally missing.

The guideline provides advice and/or tools on how the recommendations can be put into practice

Comments

There is no implementation section in the guidelines under analysis. The reader can hardly identify the tools and resources with the help of which an application can be facilitated. The authors do not introduce the links to external sources with manuals or algorithms that can be applied to the guidelines. The lack of barrier analysis and the evaluation of the lessons learned make the reader complete a serious portion of work independently. It is necessary to read the recommendations supported by various studies and reviews and underline the steps that can or cannot be taken in a particular situation. No summary documents and conclusion sections deprive a person of a chance to identify the main steps. Directions of how users may access the offered tools and resources can be discovered while reading paragraphs.

The potential resource implications of applying the recommendations have been considered.

Comments

In these guidelines, the reader can hardly find the section where cost information is mentioned. Colon cancer treatment should have its price, and the guidelines have to prepare users for certain expenses. These guidelines do not focus on the financial or economic aspects of treatment but indicate that the use of robotic colectomy as a diagnostic tool can dramatically increase operative time and costs (Vogel et al., 2017). The authors do not find it necessary to promote the use of new therapeutic resources but focus on those available at medical facilities at the moment. After reading the guidelines, the final conclusions and economic predictions cannot be made, and several questions about the cost of robotic improvements and recommendations can be raised, questioning the quality of the work done.

The guideline presents monitoring and/or auditing criteria

Comments

The key guideline recommendations do not have a separate section with specific processes or behavioral measures. However, in almost every recommendation, there are some facts with health or clinical outcome measures. For example, the identification of the regional lymph node staging depends on the number of lymph nodes that are defined as positive and measured > 0.2 mm (Vogel et al., 2017). Other important auditing information includes the peculiarities of the treatment of the malignant polyp and the analysis of its morphology. Increased risk of nodal disease because of metastases in polyps which are >2 mm are characterized by poor differentiation and tumor budding (Vogel et al., 2017). Although the descriptions and definitions are present in the guidelines, they cannot be defined as full because much information has to be additionally found.

Domain 6. Editorial Independence

The views of the funding body have not influenced the content of the guideline

Comments

In the chosen guidelines, there is no acknowledgment section with a number of names or organizations being discovered. There are also no funding bodies that could influence the content of the guidelines. Still, in the correspondence section, the name of Scott Steele is mentioned, and the role of this person cannot be ignored. These guidelines are developed by the team of the Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Therefore, the contributions of the members of this organization are significant but cannot be defined as crucial external funding sources. At the same time, Steele is not a funding body but a person who shares his experience and check the validity of data given in the guidelines. In general, the views of the potential funding bodies do not influence the recommendations.

Competing interests of guideline development group members have been recorded and addressed

Comments

No description of the competing interests, their types, and methods for a solution is mentioned in the guidelines. The development of the guideline process is free from conflicts of interests and judgments that can change the results of interventions or promote some new outcomes of the treatment process. No recordings of personal information or additional external factors that may influence the reader’s understanding of the guidelines are developed. As a result, it is impossible to identify the methods with the help of which the members of the development group can solve their conflicts or strengthen their statements and approaches. Finally, because of the absence of original research being developed and the use of the results of the literature review, the recommendations lack personal perspectives where authors are free to develop their opinions, attitudes, and contributions to the offered topic.

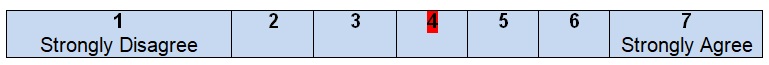

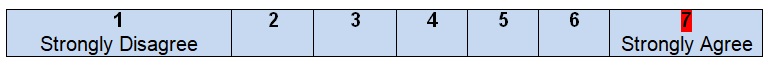

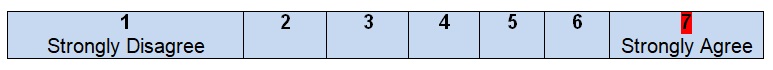

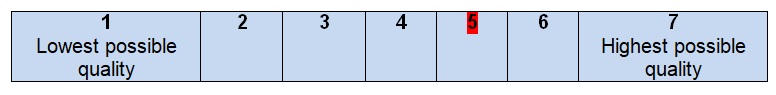

Overall Guideline Assessment

- Rate the overall quality of this guideline.

- I would recommend this guideline for use.

Notes

The overall guideline assessment (5 out 7 points) shows that the level of quality of all the recommendations for the treatment of colon cancer is high. The offered guidelines can be applied to different hospitals in the United States as well as in other countries with a similar level of life and health care quality. The authors do not focus on the development of the acknowledgment; as a result, it is hard to recognize all the possible funding bodies and costs that may be required to meet the standards of health care. Colon cancer is a problem that bothers thousands of people annually and becomes the third leading cause of death. People have to understand what they can do to predict the complications associated with colon cancer, and healthcare professionals must provide help to all people regardless of their gender, age, nationality, or religion. The contribution of these guidelines remains high as they create a solid background for the discussion of various diagnostic tools and vital signs measurement.

In addition to weak editorial discussions, not much information is given about the applicability of the guidelines. Much attention is paid to the evaluation of evidence and its role in understanding the chosen topic. However, the reader can barely get a clear picture of how these recommendations and measurements have to be used in real-life settings. Therefore, the improvements in applicability and editorial independence domains must be promoted to achieve the desired clarity of presentation and easiness in using the guidelines. The worth of evidence is high, but personal experience and the description of different situations cannot be neglected to make the guidelines clear and unambiguous to the reader. New sections should be added to the already offered guidelines with the role of each developer being properly discussed.

Conclusion

To conclude, the development of the clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of colon cancer is as difficult, challenging, and important as the creation of this critical appraisal. Many hospitals do not pay much attention to the prediction and recognition of colon cancer signs and symptoms. As a result, healthcare practitioners are not aware of the basic steps in staging and treating colon cancer and address various sources for help. The quality of the guidelines developed by the group of people from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons turns out to be a good portion of work that can be improved in case a list of recommendations and adjustments are made. Healthcare interventions that are based on the chosen clinical practice guidelines can improve the quality of life and decrease the number of deaths because of colon cancer in both male and female patients.

References

American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. (2018). Clinical practice guidelines. Web.

American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. (n.d.). Contact us. Web.

Becerra, A. Z., Probst, C. P., Tejani, M. A., Aquina, C. T., Gonzalez, M. G., Hensley, B. J., … Fleming, F. J. (2016). Evaluating the prognostic role of elevated preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen levels in colon cancer patients: Results from the National Cancer Database. Annals of Surgical Oncology, 23(5), 1554–1561. Web.

Engelmann, B. E., Loft, A., Kjær, A., Nielsen, H. J., Berthelsen, A. K., Binderup, T., … Højgaard, L. (2013). Positron emission tomography/computed tomography for optimized colon cancer staging and follow up. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology, 49(2), 191–201. Web.

Godhi, S., Varshney, V., Saluja, S. S., & Mishra, P. K. (2015). Should preoperative chest CT be recommended to all colon cancer patients? Annals of Surgery, 262(6), 123. Web.

Guyatt, G., Gutterman, D., Baumann, M. H., Addrizzo-Harris, D., Hylek, E. M., Phillips, B., … Schünemann, H. (2006). Grading strength of recommendations and quality of evidence in clinical guidelines. Chest, 129(1), 174–181. Web.

Hogan, J., Samaha, G., Burke, J., Chang, K. H., Condon, E., Waldron, D., & Coffey, J. C. (2015). Emergency presenting colon cancer is an independent predictor of adverse disease-free survival. International Surgery, 100(1), 77–86. Web.

Kahi, C. J., Boland, C. R., Dominitz, J. A., Giardiello, F. M., Johnson, D. A., Kaltenbach, T., … Rex, D. K. (2016). Colonoscopy surveillance after colorectal cancer resection: Recommendations of the US multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology, 150(3), 758–768. Web.

Koh, D. C., Luchtefeld, M. A., Kim, D. G., Knox, M. F., Fedeson, B. C., VanErp, J. S., & Mustert, B. R. (2009). Efficacy of transarterial embolization as definitive treatment in lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Colorectal Disease, 11(1), 53–59. Web.

Murphy, C. C., Sandler, R. S., Sanoff, H. K., Yang, Y. C., Lund, J. L., & Baron, J. A. (2017). Decrease in incidence of colorectal cancer among individuals 50 years or older after recommendations for population-based screening. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 15(6), 903-905. Web.

Ng, L. W. C., Tung, L. M., Cheung, H. Y. S., Wong, J. C. H., Chung, C. C., & Li, M. K. W. (2012). Hand-assisted laparoscopic versus total laparoscopic right colectomy: A randomized controlled trial. Colorectal Disease, 14(9), 612–617. Web.

Nordlinger, B., Sorbye, H., Glimelius, B., Poston, G. J., Schlag, P. M., Rougier, P., … Gruenberger, T. (2008). Perioperative chemotherapy with FOLFOX4 and surgery versus surgery alone for resectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer (EORTC Intergroup trial 40983): A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 371(9617), 1007–1016. Web.

Park, J. S., Choi, G.-S., Park, S. Y., Kim, H. J., & Ryuk, J. P. (2012). Randomized clinical trial of robot-assisted versus standard laparoscopic right colectomy. British Journal of Surgery, 99(9), 1219–1226. Web.

Parnaby, C. N., Bailey, W., Balasingam, A., Beckert, L., Eglinton, T., Fife, J., … Watson, A. J. M. (2012). Pulmonary staging in colorectal cancer: A review. Colorectal Disease, 14(6), 660–670. Web.

Rahbari, N. N., Bork, U., Motschall, E., Thorlund, K., Büchler, M. W., Koch, M., & Weitz, J. (2012). Molecular detection of tumor cells in regional lymph nodes is associated with disease recurrence and poor survival in node-negative colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30(1), 60–70. Web.

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., & Jemal, A. (2017). Cancer statistics, 2017. A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 67(1), 7-30. Web.

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Fedewa, S. A., Ahnen, S. A. Meester R. G. S., Barzi, A., & Jemal, A. (2017). Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 67(3), 177-193. Web.

Ullah, S., Anderson, R., French, N., Gardiner, A., Krupa, K., & Chisholm, L. (2015). Preoperative staging CT thorax in patients With colorectal cancer. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, 58(6), 390. Web.

Vogel, J. D., Eskicioglu, C., Weiser, M. R., Feingold, D. L., & Steele, S. R. (2017). The American society of colon and rectal surgeons clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of colon cancer. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, 60(10), 999-1017. doi: Vogel, J. D., Eskicioglu, C., Weiser, M. R., Feingold, D. L., & Steele, S. R. (2017). The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Colon Cancer. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, 60(10), 999–1017. Web.

Yun, J.A., Huh, J. W., Park, Y. A., Cho, Y. B., Yun, S. H., Kim, H. C., … Chun, H.-K. (2014). The role of palliative resection for asymptomatic primary tumor in patients with unresectable stage IV colorectal cancer. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, 57(9), 1049–1058. Web.