Introduction

Nursing education requires one to consider different aspects of personal and professional growth as well as multiple disciplines related to health care. Prospective Masters-prepared advanced practice nurses (APNs) have to achieve many goals before obtaining the ability to practice independently. The objectives set in this course include the full understanding of personal responsibility and accountability for clinical decisions. Moreover, future APNs need to commit to making ethical choices that are informed by patients’ culture and individual needs. The wellbeing of society, as a whole, also cannot be neglected, and nurses need to learn how to think about global and local goals and issues. The multitude of duties that nurses have to perform and the skills that they need to acquire seems overwhelming. Thus, it is crucial for future professionals to approach any learning process with a systemic viewpoint, addressing each aspect of nursing education with principles and competencies in mind.

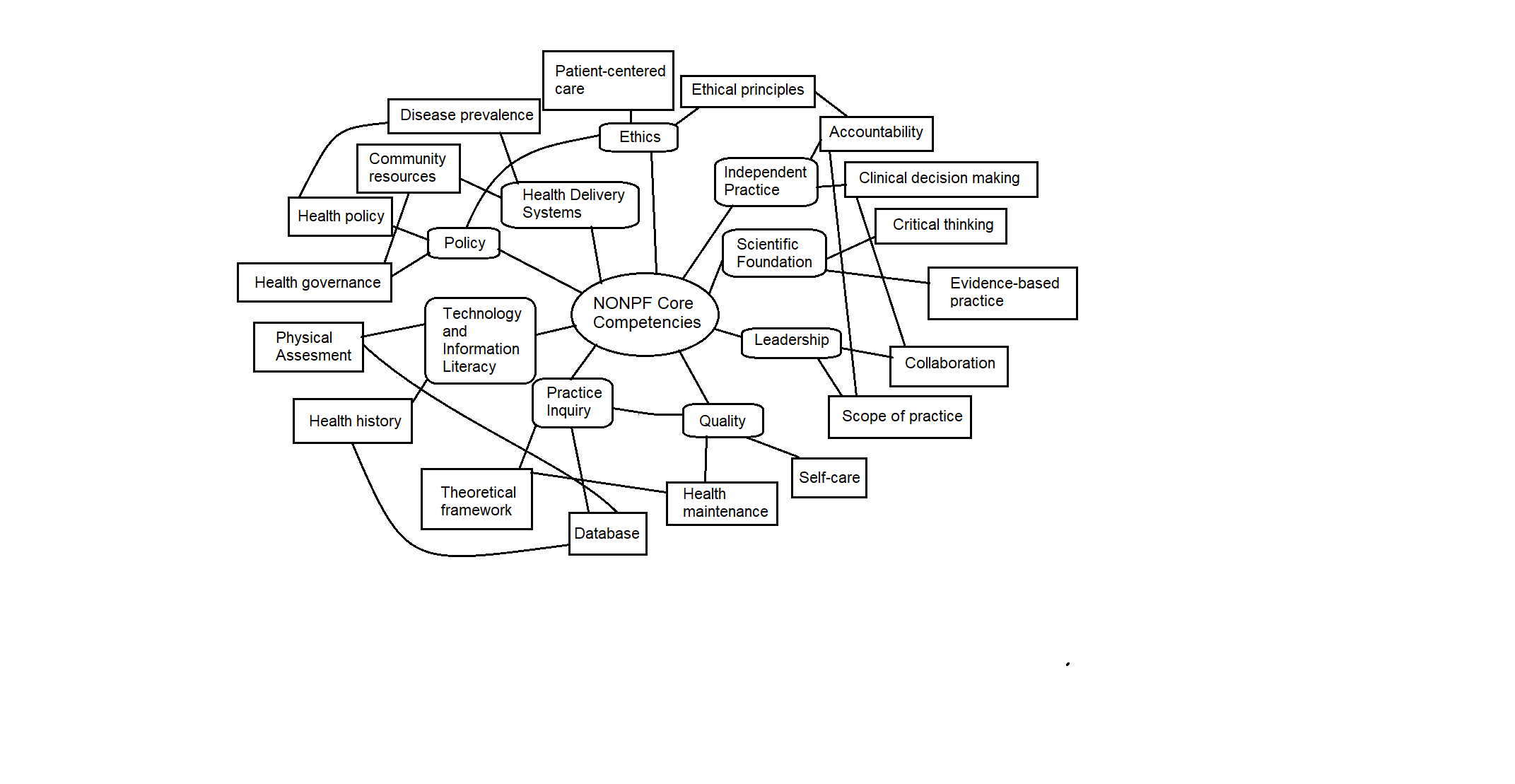

The present research presents an assessment of previously completed assignments, offering their appraisal and connection to the Program’s Outcomes (PO), the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) Master’s of Science in Nursing (MSN) Essentials, and the National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties’ (NONPF) Core Competencies. The ten presented exemplars describe the most valuable pieces of work that I completed during this course to prepare for my future as a Masters-trained APN. Apart from considering how these assignments allowed me to achieve the competencies required by this profession, I also provide some self-reflection about each project. Reflecting is a vital part of continuous learning, valued in the field of nursing. With this investigation into my previous achievements, I aim to prove that my training has prepared me to assume the title of the APN.

Exemplar # 1: NR 505 Advanced Research Methods: Evidence-Based Practice

Early Mobility in the Intensive Care Unit

Early mobilization therapy issue became an area of concern after researchers discovered the negative consequences of bed rest following a sickness or trauma. These consequences can be versatile and dangerous for a patient’s health condition. The most prominent of them are cardiovascular deconditioning, increased risk of pressure ulcer development, muscle weakness and atrophy, neurological dysfunction. Thus, the given reasons are enough to support the need for developing an EBP project in this area (Patel, Pohlman, Hall, & Kress, 2014).

The nursing issue that has been chosen is the early mobility in the intensive care unit (ICU). Particularly, the advantages and the disadvantages of the early mobility therapy compared to the non-early mobility therapy for patients who are in intensive care will be analyzed. The reason for choosing this particular topic is that it is a significantly important issue in nursing practice. However, the amount of evidence that has studied the early mobilization of seriously ill patients is rather small. A few randomized and controlled researches have been conducted including only several hundred patients which significantly limits the strength of the evidence. Therefore, since the early mobilization therapy is considered safe and feasible, it is important to pay more attention to it (Schaller et al., 2016). Thus, this assignment consists of the following sections: Introduction, The Connection between FNP and Early Mobility Therapy, Nursing Issue, PICO Question, Research Literature Support, Theoretical Framework and Change Model, Research Approach and Design, Sampling Method, Conclusion, and References.

The Connection between FNP and Early Mobility Therapy

The specialty track that has been chosen is the Family Nurse Practitioner (FNP). FNPs are advanced practice nurses who work autonomously or in cooperation with other healthcare professionals to provide family-focused care. They provide a wide range of healthcare services for particular family units on the long-term basis. FNPs’ objective is to promote health, prevent diseases, treat patients, and counsel them across the lifespan. The role of an FNP in the early mobility therapy in the ICU is significant. FNPs look after patients when they are in intensive care.

In this regard, they can help implement the early mobility therapy during the treatment of their patients (Bernhardt, 2017). Thus, depending on the type of illness or injury, FNPs can determine whether to use early or non-early mobility therapy on their patients. Although in general, early mobility therapy helps prevent negative consequences caused by bed rest, in certain cases, it can lead to the relapse of a disease or to the opening of an undertreated wound. Therefore, FNPs’ purpose is to decide whether this therapy will harm a patient in a particular case or improve patient’s health, accelerate the healing process, and help avoid pernicious consequences connected with the non-early mobility therapy.

Nursing Issue

The nursing issue on which this project is focused is the early mobility program in the ICU. There has recently been an increase in the movement to begin research that focuses on the physical therapy utilization within the ICU establishment and the outcomes of the early intervention program with patients within this establishment. Progressive or early mobilization includes a system of movements that increase the activity of a patient beginning with the passive set of movements and ending with the independent ambulation. After the implementation of the early mobility therapy, patients will begin a special movement therapy in 24-48 hours after the mechanical ventilation (Schaller et al., 2016). The early mobility therapy had been implemented until recently. For several years, many researches were conducted in order to identify the advantages and disadvantages of this therapy. Eventually, a couple of years ago, some hospitals started to implement it. Thus, as for the frequency of the occurrence of this therapy, it is not frequent, as it is a new therapy, but those who have started to use it demonstrate chiefly the positive results (Reade & Finfer, 2014).

The initiation of the therapy begins after the establishment of the clearance from a physician or a medical team responsible for the ICU patients (approximately a week) and after the occupational therapy and/or the physical therapy has been consulted. Currently, numerous attempts are being made to launch more trials of the early mobility therapy for the ICU patients in combination with the interruption of sedation during the therapy time. Additionally, the implementation of the early mobilization protocol requires a multidisciplinary approach that includes collaboration between physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, rehabilitation therapists, and administrators. Thus, this issue will engage all stakeholders, including improvement team leaders, senior leaders, and frontline staff who will be involved in the process of its implementation (Schaller et al., 2016).

Thus, this project will attempt to present evidence on the advantages and the disadvantages of the early mobility therapy in the ICU in contrast to the non-early mobility therapy. The rationale for choosing this particular nursing issue is that it is important and relevant now and requires much attention and effort on the side of all the stakeholders in order to be successfully implemented in nursing practice. Additionally, due to the lack of practical evidence of the positives and negatives of the early mobilization therapy, it is crucial to conduct further research on this issue in order to accelerate its overall implementation. Moreover, this therapy has already proved to be safe and efficacious (Bernhardt, 2017).

PICO Question

Currently, the problem of the implementation of the early mobility therapy in the ICU is relevant. Many types of research have been made since the first attempts to introduce this new program. Recent literature supports the need for this program, stating that it will help avoid the undesirable effects that can be caused by a long bed rest and improve patient’s health (Reade & Finfer, 2014). Based on the identified need for the early mobility therapy development in the ICU and the current relevance of the identified nursing issue the following PICO question is created to guide this project: In severely ill or injured patient in the ICU does early mobilization therapy results in ameliorated functional state and decrease ICU stay as compared to the non-early mobilization therapy? The main criterion for the search was the scholarly or peer-reviewed articles and journals using reliable databases like CINAHL, EBSCO, Medline Complete, PubMed and Google Scholar Search. The key terms used in the literature search were critically ill patients, early ambulation, early mobility, bed rest, intensive care units, physical therapy, quality improvements, rehabilitation, therapy, and mechanical ventilation.

Research Literature Support

Leditschke, Green, Irvine, Bissett, and Mitchell (2012) conducted a quantitative study, with the purpose to find out benefits of early mobilization of critically ill patients in the ICU and identify the frequency of this therapy. The research was a 4-week prospective audit on 106 patients from a mixed medical-surgical tertiary ICU, whose mean age was 60 years, median ICU length of stay was one day, and median hospital length of stay was 12.5 days. They were subject to: 1) active mobilization, which consisted in marching on the spot for more than 30 seconds); 2) active transfer from bed to chair; 3) passive transfer. The researchers collected de-identified data on the number of days the patient was mobilized, the type of mobilization used, adverse factors, and reasons mobilization could not take place. It was found out that participants were mobilized on 176 of 327 days spent in ICU. There were 2 adverse events that occurred during 176 mobilization episodes (1.1%). It was concluded that it was possible to mobilize critically ill patients for the majority of days of their stay in the ICU starting from the first (which supports the PICO of the study at hand). The key strength of the study is its scope and practical recommendations. Its major limitation is that no evidence proves that early mobilization is more effective than non-early therapy. The solution is to perform a similar study to compare the effects of the two approaches.

Engel, Needham, Morris, and Gropper, (2013) performed a qualitative study of the three selected medical centers as for the success of their ICU early mobilization programs. The major purpose of the research was to compare and contrast the impact an early mobility program produced on severely ill patients in three hospitals. The researchers used an interprofessional approach based on teamwork. As a result, the length of stay was reduced both in the ICU and in general care. Moreover, in all the three medical centers, this intervention also managed to lower the level of delirium and practically eliminated the need for sedation for the participants. This allowed concluding that ICU early mobility quality improvement program is capable of improving patient outcomes, which supports the PICO. The strength is that the described program can easily be applied to other types care units. Yet, there are no exact numeric indicators of the improvement, which is a limitation. The solution is to conduct a quantitative study to obtain statistical evidence.

Sricharoenchai, Parker, Zanni, Nelliot, Dinglas, and Needham, (2014) conducted a prospective observational study aimed to identify whether it is safe to use early mobilization therapy interventions in the ICU for reducing impaired physical functioning. The authors of the study explored how often and under what conditions some of 12 kinds of physiological abnormalities and safety risks presented by the implementation of mobilization therapy could appear. As a result of the experiment, 1787 patients with an ICU stay lasting minimum 24 hours, 1110 (62%) took part in 5267 mobilization sessions. All sessions were organized and performed by 10 therapists during 4580 days. A total of 34 (0.6%) of these sessions revealed safety risks or physiological abnormalities. None of these required any additional costs or prolonged stay, which supports the effectiveness of the therapy indicated in the PICO. The strength of the study is its huge sample size increasing liability and validity of the experiment. Its limitation is that only one hospital was involved in the research. The solution is to repeat the experiment in other hospitals which will include the influence of clinical factors as a variable.

Lord et al. (2013) performed a quantitative study, collecting data from articles and from the actual implementation of the program and created their own model of net financial savings. The researchers’ major goal was to evaluate how much annual costs implementation of the ICU early mobilization therapy allows saving. The intervention consisted in financial modelling of results for the implementation of the early mobilization program. The researcher presented the results of using the developed model for ICUs with 200, 600, 900, and 2,000 annual admissions. It was identified that $817,836 of cost savings could be achieved through the implementation of the program in the example scenario with 900 patients per year. These savings were generated through stay reductions of 22% (for ICU) and 19% (for floor). This implies that the program indeed allows saving costs through the amelioration of patients’ condition (which again supports the PICO). The key strength of the study is that a new model was developed that relies on actual experiments of the program implementation. The limitation is that there is hardly any novelty except the implementation of a new tool. The solution would be to apply the same tool to compare the effects of different types of mobilization therapy as this may give unprecedented results.

Theoretical Framework and Change Model

For the purpose of this project, Lewin’s Change Theory was selected as a theoretical framework as it provides a method to successfully implement a planned change (the one occurring by design). The main concepts of the theory are field and force. The former is a system, which means that in case one of its elements changes, the whole body of it is affected. Change is viewed in a disrupted balance of driving and restraining forces. While a driving force initiates movement or shift towards transformation, a restraining force is the one hindering the process. In case of the early mobility issue, the driving forces include: educational programs for staff and patients, evidence-based literature supporting early mobilization, administration support, etc.

Restraining forces are numerous: patients’ reluctance to try early mobilization as a part of general resistance to change, nurses’ unwillingness due to the fear of accident extubation, patients’ delirium, oversedation, lack of specific policies and comprehensive programs, etc. Thus, according to the chosen theory, it is needed to: 1) unfreeze the status quo; 2) gradually introduce changes; 3) freeze the change making it durable by assimilating in the system. Success and sustainability of the project intervention will be ensured by the capability of the framework to allow better understanding of patients’ needs and fears and developing an implementation plan in accordance with these factors. An education program will be required to integrate early mobilization into practice since it cannot simply be imposed upon ICU patients if they opt for non-early intervention or no mobility at all. Lewin’s framework will make it possible to change the entire system through an individual change.

The implementation of the proposed change will be guided by Logic Model for Program Development since it allows planning the desired outputs, outcomes, and the general impact of the change in advance. The model also makes it possible to measure both patients’ and nurses’ knowledge concerning the benefits of early mobilization in the ICU in order to assess what training will be required (Chen, 2014).

Research Approach and Design

Since the research goal is to answer whether a severely ill or injured patient will have an ameliorated functional state and a decreased stay in hospital with the realization of the early mobilization therapy compared to the non-early mobilization therapy, it would be reasonable to opt for a quantitative approach. The design is going to be experimental. It will test a hypothesis through an intervention, the impact of which will be the major focus of the study. Furthermore, the experiment is required to look for the ways to improve condition of real patients. The choice of this approach is accounted by the fact that it allows controlling the study conditions using precise measures and strict regulations of all variables. The major advantage of the quantitative study is that it is possible to generalize the results from a sample to a larger group of the population. Yet, there is also a disadvantage: The research design does not allow discovering anything new since it is purely deductive.

Sampling Method

The target population that the study is going to address will include severely ill or injured patients from 25 to 65 years of age undergoing treatment in the ICU. Non-probability sampling will be used, which is supported by the fact that only patients of a particular age group who currently suffer from acute diseases or injuries will be eligible to participate in the research. This type of sampling was selected due to the fact that it allows researchers to focus on a particular group of patients (as it would be wrong to involve patients from the general care unit in the same experiment).

The following steps will constitute the sampling procedure:

- establishing eligibility criteria;

- choosing a random sample of patients from 25 to 65 undergoing treatment in the ICU;

- informing the participants about the goals of the research and obtaining their informed consent;

- collecting background information about the participants in order to decide on variables;

- dividing the patients into the control (receiving non-early mobilization therapy) and intervention groups (undergoing early mobilization); each group will include approximately 50 participants.

The two major advantages of this sampling procedure is that: 1) non-probability sampling implies that only patients meeting the criteria will be able to participate–therefore, the intervention will be thoroughly controlled and the results will be precise; 2) at the same time, randomized trial will eliminate bias. Yet, there is also a disadvantage: Non-probability samplings practically do not take into account extraneous variables, which can be influential.

Institutional Review Board help researchers protect participants’ rights relying on the following principles:

- obtaining an informed consent;

- respecting confidentiality and privacy;

- discussing the limits of confidentiality (informing participants what data will be made public and how it will be used) and preventing their violation;

- informing participants about federal and state laws that protect their rights.

Conclusion

It has long been unclear whether early or non-early mobilization therapy is preferable for patients in the ICU as the former might lead to aggravation of the patient’s condition whereas the latter is usually less effective. The role of FNPs is crucial since they must decide whether the selected therapy will harm a patient or improve their overall health.

However, according to the results of the experiments conducted by other researchers, it was found out that early mobilization therapy brings about the expected improvements in most cases, which means that the outcomes for this project proposal will be positive.

PO #4: Integrate professional values through scholarship and service in health care (Professional identity)

This program outcome was met because, in this assignment, I gathered data about the research question and evaluated it to introduce evidence-based knowledge into practice. The suggestion for implementing early mobility interventions was based on previous findings, thus showing my ability to integrate scholarship into the field of health care. It is notable that the program outcome considers one’s ability to use scholarship a professional identity, thus highlighting the need to understand the scientific foundations of any practice activity. By examining an initiative and comparing its results with those of other programs, I have supported my professional identity.

AACN MSN Essential I: Background for Practice from Sciences and Humanities

This essential was addressed in the paper since the topic of my study was focused on drawing knowledge from various areas of health care research. The investigation into the outcomes of introducing an early mobility initiative to an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) utilized a theoretical framework of Lewin as well as previous findings about the effectiveness of similar projects. As a result, I was able to combine specific information from different disciplines for practice improvement.

NONPF Core Competency 4: Practice Inquiry

The present research paper followed and met the objectives set by the fourth NONPF competency. I investigated previous scholarly research, introduced a theoretical framework for the project, utilized my skills in searching medical databases, and presented the results of my investigation. Moreover, I analyzed the consistency of my findings with the existing scholarship and reflected on their impact on future investigations.

Concepts and Reflection

A theoretical framework is the first concept introduced in this assignment. It is a foundation for research papers, created to support the structure of an investigation. Authors can choose a framework to guide their examination and inform their selection of participants, data gathering methods, and analyzing tools. A theoretical framework’s choice can determine the path which a researcher may take when exploring a posed question.

The second concept is a database which is reviewed in relation to medical publications. It is a collection of books, journal articles, and clinical guidelines that present the latest findings in the field of health care. Nurses have to understand how to search for relevant information using these databases and how to appraisee the selected sources to choose the most reliable data and integrate it into their research.

The present exemplar allowed me to exercise my critical thinking and investigate a problem that exists in health care right now. I used various databases and gathered the information that helped me to evaluate the usefulness of early mobility programs for patients in the ICU. The in-depth consideration of the issue revealed that the current research of it was lacking. However, the available findings supported the notion that a change in mobility initiatives could improve patients’ health. As an outcome, this assignment informed my opinion about activities that could be introduced to ICUs and led to me forming a program for practice change.

I also examined the connection between Family Nurse Practitioners (FNPs) and early mobility therapy, assessing their role in improving care in the ICU. I understood that the initiative for launching more trials to test early mobility programs requires FNP’s participation since they have an opportunity to build strong relationships with their patients. The choice between early and non-early therapy is often dependent on nurses’ decisions. Thus, the ability to consider research data is a vital skill that increases nurses’ quality of care.

Exemplar # 2: NR 506 Health Care Policy

Significance of the Problem

A public health policy issue I am interested in concerns depression among high school students. Only about 40 years ago, depressive disorders in adolescents were largely neglected since most physicians doubted that the problem could exist at such an early age. However, it has been proven depression may not only appear in teenagers but also increase associated morbidity and mortality rates. Therefore, the importance of the issue is hard to overestimate as plenty of human lives are at stake.

The proposed policy is to introduce depression screening at schools to detect the problem in time. The immediate target of the policy is local level. Later, the issue will have to be discussed at the state level since it is not enough to solve the problem only locally. There is a necessity to develop universal guidelines for screening that would be applicable in all schools across the state. This will considerably facilitate the procedure of policy implementation via standardization. The legislator that is to be contacted first is Janice Kerekes, Clay County Board Member Representative, District 1.

Analysis of the Problem/Empirical Evidence

The specific problem surrounding the issue of depression among adolescents is the absence of timely diagnosis as the first step to depression management. More than 30% of depressed adolescents are not recognized and do not receive treatment, while the clinical spectrum of their condition may vary from simple sadness to bipolar disorder, which can be irreversible if not detected in due time. The research shows that approximately 9% of school students at the end of adolescence meet criteria for depression whereas 20% of them state that they suffer from the condition since early childhood (Allison, Nativio, Mitchell, Ren, & Yuhasz, 2014).

Currently, there is no regulation that would oblige schools to conduct screening that would allow detecting the condition in high school children. Thus, in order to improve the situation, it is necessary to introduce changes to regulatory issues. Mandatory annual screenings for adolescents are recommended as the most effective option. Nurses will be for conducting them in high schools. This necessity is supported by the fact that depression is now the major cause of psychosocial impairments, increased hospitalization, alcohol and drug abuse, antisocial behavior, and suicide. There is also evidence that more than 50% of cases of negative mood changes in adolescents can be eliminated through social therapy that makes it possible to monitor and modify distorted thinking by encouraging social activities and resolving conflicts (Allison et al., 2014). This helps prevent severe impairments of the psyche caused by clinical depression. In case of a more serious condition, early intervention makes it easier to do without antidepressants or tranquilizers and mitigate the effects with psychotherapy only.

Impact and Importance to Nursing

There is evidence showing that screening with standardized and validated questionnaires lead to early recognition and treatment, which is more effective than waiting for more severe symptoms to be apparent, resulting in lower cost and better outcomes. The costs include psychiatric hospital admissions, emergency visits, total mental health costs, poor school attendance for the teen and work absences for parents. The Patient Health Questionnaire Modified for Teens (PHQ-9 Modified) is a well-accepted, standardized, validated questionnaire, used by many providers for patients between the ages of 11 and 20 and takes less than five minutes for them to complete. It can also be administered and scored by a school nurse for screening depression among high school students. Since the problem have long-term consequences and lead to poor school performance, family relations, and state of health, neglecting it may mean that in future, nurses will have to deal with the population, suffering from a whole spectrum of mental conditions therefore annual screening is crucial for schools to introduce.

Analysis of the Policy Issue

Context

School is the main place outside home where teenagers spent the majority of their time. Therefore, detecting behavior deviations and providing preventive measures is the primary responsibility of a school nurse. Despite the fact that there are two acts regulating suicide prevention (the Youth Suicide Prevention Act of 1987 and public Health Service Act of 1990), there are not universal guidelines for screening and follow-up. Having no elaborated plan of action, school superintendents often have to decide for themselves how to manage the problem. Researchers have found that no program of those that have been developed has been tested in randomized trial, which means that none of them are evidence-based.

Goals/Options

The ultimate goal of depression screening it to create a list of depression indicators on the basis of the observed cases for teachers and parents to be able to identify the problem at an early stage. In addition to creating other learning conditions to those whose depression is getting aggravated owing to the unfavorable environment a nurse could provide a referral for psychotherapy to teenagers suffering from various forms of depression based on the gravity of the condition. Lastly, ensuring follow-up and cooperation with parents are maintain for continuity of care.

There are three major options for schools to choose from: 1) to include problem education into the curriculum programs; 2) to provide training for teachers; 3) to introduce regular screening.

Evaluation of Options

Although the first option has been studied more profoundly, its effectiveness is still doubtful. On the contrary, there is extensive evidence that curriculum programs do not prevent depression or suicidal behaviour in high school students. They do not feel that theoretical education is connected with their real-life condition (Prochaska, Le, Baillargeon & Temple, 2016). Moreover, many of them try to conceal it out of fear of bullying.

The second option, in-service training for teachers can potentially assist them in identifying students that are at risk. However, there is little research on the efficacy of the measure, which does not allow making inferences about its superiority over the other two (Cunningham & Suldo, 2014). Besides, the assessment of a person without medical education can be rather subjective.

Finally, the third option involves comprehensive evaluation of students’ psychological state including self-reported data, results of various psychological tests, and interviews (Prochaska et al., 2016). This measure is more preferable since it can be applied in all schools regardless of the curriculum and provide more objective results.

Recommended Solution

It is recommended to issue a new regulation for schools obliging them to introduce a depression screening program for high school students. At the first stage of the program, students will need to complete an evaluation form, the major goal of which is to identify those who are at elevated risk. At the second stage, the risk group is assessed via computer tests. At the final stage, a school nurse interviews those students whose results raise concerns to be able to diagnose their stage of depression.

Policy makers have to provide schools with psychometrically validated screening tools that must be tested as per their sensitivity (the ability to detect students with depression), specificity (the ability of identifying those who do not have any related conditions), positive predictive value (the relation between whose who screen positive and who are actually positive), and negative predictive value (the relation between whose who screen negative and who are actually negative).

Status Updates

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry provides updates on this and other topics related to mental health of children and teenagers. The website of the organization features numerous annual reports and recommendations for all stakeholders involved. Furthermore, there are also strict pharmaceutical guidelines for every mental disorder. The academy has a 60-year history in the field and therefore can serve as a reliable source of information on policy and other psychological conditions.

Conclusion

There is a nationwide problem with detection, treatment, and prevention of teenage depression. For nurses, it means that the quality and nature of care delivery may be negatively affected by the wrong diagnosis. Since the problem is fraught with long-term consequences and lead to poor socialization, performance at work, family relations, and state of health, neglecting it may mean that in future, nurses will have to deal with the population, suffering from a whole spectrum of mental conditions. Thus, due-time screening is crucial for schools to introduce.

AACN MSN Essential VI: Health Policy and Advocacy

The assignment discussing depression prevention among high schoolers helped me examine the ideas of health policy and advocacy. This essential is concerned with the ways in which nurses can impact health care through policy development and systemic change. I investigated the current approach to high school programs for depression detection and prevention and designed a policy proposal for a change on a local level. I explored strategies for disseminating the information about my proposition to appropriate legislators. Furthermore, I learned how to present the data about the problem to demonstrate why new policies are necessary. For instance, the finding that no regulations for depression screening in educational facilities exist shows that children’s mental health is not prioritized enough in health and educational policies. New approaches to screening regulations can improve depression detection and allow health care professionals to treat students on time.

NONPF Core Competency 6: Policy

The sixth competency was met in the assignment about depression among high school students. It requires nurses to demonstrate a high level of understanding of connections between policy and practice (NONPF, 2017). Here, the link is apparent – regulations for screening would improve nurses’ reach to the population of young students and their health. Moreover, it would change the view of depression and possibly reduce rates of negative consequences, including self-harm and suicidal ideations. As evidence suggests, advocacy for depression evaluation can increase children’s access to psychotherapy, preventing deterioration and necessity of pharmacological intervention. The assignment evaluated the proposed policy to support its goal of creating a safe and healthy practice for students. As an outcome, I was able to see how policy leads to positive change and contributes to global issues’ solution.

Concepts and Reflection

The first explored concept is health policy- a set of actions and plans that are created to achieve specific health-related goals through health care. A policy can set target goals for organizations and communities to reach in a specific time period. Moreover, it may describe a particular vision with which entities should align their initiatives. It also determines priorities and assigns roles to stakeholders, informing all involved persons.

Health governance is another concept – it is a set of actions taken by a government body to improve the health care sector (de Leeuw, 2017). It includes the creation and assessment of health policy, also considering financial, social, and political aspects of each decision. Governance ensures that policy responds to the emerging trends and issues and furthers the state of national health. Furthermore, it regulates policy implementation and assessment and establishes tools for accountability.

The investigation into the problem of undetected depression in students showed me the extent to which health policy can benefit large groups of people. The impact of health policy is substantial – it can prevent various population-wide issues and change the course of health care. However, its development is challenging as it requires one to consider how the national system operates currently and what changes are possible. The lack of regulation, for example, raises concerns and shows that policy should incorporate clear instructions for schools to adopt. While completing this assignment, I understood that policy has to provide solutions that are not only beneficial to people but also well-researched, stable, and practical. Multiple approaches are reviewed in the paper, including problem education, teacher training, and regular screening. The analysis shows that the third option is the most reliable, thus being a potential foundation for policy change.

Exemplar # 3: NR 503 Health, Epidemiology & Statistical Principles

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Florida

Chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) is cited among conditions contributing to the pulmonary cancer etiology (Aldrich et al., 2015). Consequently, there has been an urge to intensify research to determine the interrelationships between the two disorders to invent improved strategies for reducing their impact on society. Lung cancer causes the highest number of cancer-related deaths in the United States, while COPD is the third primary cause of general mortality, and the combination of the two creates an immense public health burden, causing significant disability, morbidity, and mortality (Aldrich et al., 2015). The average total annual cost of COPD for the year 2010 was $49.9 billion, and the chances of being employed plunged by 8.6% for those with the COPD linked disability (Doney et al., 2014). The statistics released in 2015 from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) indicated a 9.6% countrywide incidence rate for the self-reported COPD cases in grownups aged 40 years or more (Aldrich et al., 2015). It also showed that a regional variation of the disease across the USA with Southern States recording the highest prevalence rates (Aldrich et al., 2015).

Background of the Disease

COPD is a manageable and curable lung disease with some important non-pulmonary effects that may contribute to the severity in individual patients (Reid & Innes, 2014). The pulmonary constituent of the sickness is typified by an almost irreversible breathing limitation that is gradual and accompanied by an unusual allergic reaction of the lungs due to noxious gases and particles (Reid & Innes, 2014). Accompanying diagnoses include chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive bronchitis and emphysema. Chronic bronchitis is characterized by the persistent copious mucus production into the bronchioles with the presence of a cough most of the time for no less than three consecutive months in two successive years (Holt et al., 2015). In contrast, emphysema is the permanent hyperinflation of the alveoli at the end of terminal bronchioles accompanied by damage to the alveolar walls without obvious fibrosis (Reid & Innes, 2014). The stimulation of the inflammatory cells (neutrophils, macrophages, and CD+ lymphocytes) by exposure to noxious particles and gas causes the cells to release several chemical mediators –tumor necrosis factor α, interleukin 8, and leukotriene B4 – that bring about the irritation (Reid & Innes, 2014).

In addition, the impairment of the alveoli may be due to overproduction of proteases, and oxidants activity. These conditions result in difficult breathing (dyspnea), wheezing, cough, sputum production, airway obstruction, decreased blood O2 concentration and high blood CO2 levels (Doney et al., 2014). Also, this blend of weakened pulmonary function and repeated exacerbations promotes a medical condition characterized by the reduced endurance to exercise and physical activity, and deconditioning; factors that translate into disease progression, poor quality of life, disability and eventually premature death. Potential complications of COPD include respiratory infection, pulmonary hypertension, malnutrition, pneumothorax, corpulmonale, polycythemia, acute and chronic respiratory failure, arrhythmias, depression, nocturnal hypoxia, and disordered sleep (Doney et al., 2014).

COPD takes 120,000 American lives every year (Srivastava, Thakur, Sharma, & Punekar, 2015). However, the 2014 statistics indicated a reduction in age-adjusted death rates from 1999’s 57 per 100,000 for men and 35.3 per 100,000 persons for women to 44.3 and 35.4 respectively (Holt et al., 2015). The death toll from COPD in Florida in 2014 was estimated at 34.7-38.7 per 100,000 people. The state prevalence rate was 6.5 – 7.6%. The 2014 average prevalence rates for counties in Florida were 3.3 – 17.7%, while the congressional district ranges were 3.4-14.0% (Holt et al., 2015).

Surveillance Methods

To evaluate the state-level and national prevalence of COPD, the impact on the population’s value of life, and use of health care resources by patients, the CDC and the State Departments of Health use data from the BRFSS (Holt et al., 2015). For instance, the Florida Department of Health uses the Florida BRFSS State Data to obtain the state-specific, population-grounded estimates of COPD prevalence and associated risk behaviors among the residents (Holt et al., 2015). The data are useful for ascertaining issues of health of primary importance and pinpointing populations at risk of ailments, disability, and death (Holt et al., 2015). The information also supports the development and evaluation of prevention programs, community, and policy maker training about disease prevention and the reinforcement of community policies that encourage health and prevent disease (Holt et al., 2015).

BRFSS is a “state-run random-digit-dialed phone assessment of the non-institutionalized, US civilian grownups aged 18 years and above” that is conducted yearly by the CDC health divisions at the state level in homes accessible via phone calls (Holt et al., 2015, p. 8). The response rate for BRFSS is computed using specific criteria or response formula and is the proportion of the number of people who complete the survey to that of the eligible persons (Holt et al., 2015).

Descriptive Epidemiology Analysis

Disease prevalence is related to multiple health and socioeconomic factors. It has been approximated that 10 -16 million persons in the US have been diagnosed with COPD and that 14-16 million more cases go undiagnosed (Doney et al., 2014). That is due to under-reporting or under-diagnosis, predominantly those cases with mild to moderate disease. In addition, self-reports of the disease may be inaccurate, making it difficult to ascertain the actual prevalence of COPD in the state (Aldrich et al., 2015). The incidence, morbidity, and mortality of this disease are increasing with the aging of the US population (Doney et al., 2014).

Risk factors for acquiring COPD include tobacco smoking (>95% of cases), biomass fuels use, occupational (coal mining or prolonged contact with cadmium), and air pollution (Reid & Innes, 2014). Other factors that predispose individuals to COPD include repeated infections and diseases such as adenovirus and HIV, low socioeconomic status, cannabis smoking, poor nutrition, genetic factors like α1-antiproteinase deficiency, and the respiratory system hyperactivity (Reid & Innes, 2014). Children with pulmonary growth and functional impairment due to low birth weight and childhood or maternal infections are at higher risk of suffering from the disease. Apparently, smoking cessation can halt the progress of COPD.

From the state data in table 1 above, it is evident that the Hispanics are less prone to COPD than the non-Hispanic Whites and the non-Hispanic Blacks (3.7% compared with 9.7% and 5% respectively). Women have a higher incidence of COPD than men (8.8% compared to 6.4%). Persons below the high school level of education often report higher disease incidences than those at advanced levels of training (13.2% in comparison to 8.3% for high school and 5.8% for college). Also, unmarried couples are more susceptible to COPD than married people (8.8% to 6.5%). Similarly, employment status correlates with reported COPD cases. Disease incidences are prevalent among the physically impaired, unemployed or retired than among the students, house makers and the employed. Verified COPD cases drop with growing household income from 11.5% among those with an annual family income <$25, 000 to 3.7% for those with annual income ≥ $50,000. Persons who have been smoking for a longer duration have a higher incidence rate for COPD than former smokers and non-smokers. The asthmatic patients are also likely to suffer from the disease as compared to the non-asthmatic persons.

Exacerbations and disease severity of COPD are accompanied by health-related quality of life and economic drain. Other critical parameters connected with increased burden are increasing age, female gender, and the presence of co-morbidities. The impact on population outcomes can be estimated by observing the overall health condition, psychological well-being, functional status, fatigue, and life quality (Srivastava et al., 2015). Drainage of economic resources occurs when patients seek treatments. Therapy is by the use of bronchodilator drugs. Further, patients with COPD often require prolonged oxygen therapy, and antibiotics are frequently used to treat exacerbations caused by bacterial infections (Reid & Innes, 2014).

Diagnosis of COPD

Diagnosis is based on medical history, physical examination, and the results from the pulmonary function tests. However, differential diagnosis is essential to discriminate COPD from diseases such as chronic asthma, tuberculosis, bronchiectasis, and congestive heart failure (Reid & Innes, 2014). The patients exhibit atypical pulmonary function test values, e.g., a lower FEV1 (Reid & Innes, 2014). The maximum volume of air that can be inhaled forcefully per second (FEV1) and FVC are essential prognostic indicators in a patient, with the average rate of FEV1 decline being an important objective measure to assess the COPD progression (Reid & Innes, 2014). FEV1 is excessively reduced in airflow obstruction conditions, leading to FEV1/FVC ratios of less than 70% (Reid & Innes, 2014). The average rate of decrease of FEV1 in healthy, nonsmoking persons due to aging is 25-30mL annually (Reid & Innes, 2014).

For smokers, the rate of decline is higher, being steepest in heavy smokers. The more severely diminished the FEV1 at diagnosis, the steeper is the rate of decline. Also, the more the number of years of smoking and the number of cigarettes smoked, the steeper the decreases in lung function. The diagnosis is through spirometry and confirmation is made when the post-bronchodilator FEV1 is below 80% of the projected figure and that the FEV1/FVC <70% (Reid & Innes, 2014). If the FEV1/FVC <70% and FEV1 is more than 80%, this may be a typical finding in adult patients or an indicator of the mild disease (Reid & Innes, 2014). The seriousness of COPD is defined according to the post-bronchodilator FEV1 as a proportion of the projected value of the patient’s age (Reid & Innes, 2014). An FEV1/FVC value of <70% and FEV1 of ≥ 80% would indicate mild disease, while an FEV1/FVC figure of <70% and FEV1 of 50-79% would suggest moderate disease (Reid & Innes, 2014). The diagnoses for severe and serious COPD include FEV1/FVC is <70% and FEV1 of 30-49% and FEV1/FVC<70% and FEV1 <30%, respectively (Reid & Innes, 2014).

Measurement of lung volumes aid in the assessment of hyperinflation and is performed either by the helium dilution technique or body plethysmography (Reid & Innes, 2014). In this case, a low gas transfer factor suggests the presence of emphysema. In addition, the exercise tests are essential in evaluation of exercise tolerance and provide a baseline on which to judge the response to bronchodilator therapy or non-pharmacological treatments (Reid & Innes, 2014). Notably, although there are no reliable radiographic signs that correlate with the gravity of airflow obstruction, a pulmonary x-ray is essential to rule out other diagnoses – cardiac failure, lung cancer or presence of bullae (Reid & Innes, 2014).

As mentioned above, spirometry is the gold standard test for diagnosis of this disease. It is a painless breathing test. In some healthcare units, this screening test is administered freely. It is an essential step to ensure an accurate diagnosis and guide medication. The international COPD guidelines – the GOLD criteria – provide recommendations for screening, disease severity classifications, medical treatment, and prescription. Guideline-based care has been shown to improve patient outcomes in COPD (Holt et al., 2015).

Plan for Action

The prospective benefit of epidemiologic knowledge is realized when it is transformed into health policy and later prototyping and implementation of disease control programs. The health planning phase involves the following key steps: assessing disease frequency, identifying the causes, evaluating the efficacy and efficiency of existing treatment, implementing interventions, monitoring activities and measuring the progress. To determine the outcome of the interventional measures or actions, it is crucial to re-measure burden-of-illness parameters, analyze trends in population groups at risk of disease, and ascertain the acceptance of various interventions after disease awareness program.

In my case, I plan to promote awareness of GOLD guidelines among GPs through training and underscore the need for adherence to them. Also, I plan to educate, inform and empower the Florida community by identifying gaps in the current public information about COPD. I intend to research more on health hazards and risk factors of COPD given the current economic, environmental and lifestyle dynamics that impose health and psychosocial strain on the people. As appropriate, I will emphasize the importance of smoking cessation; encourage attending a smoking cessation program and/or asking the treating clinician about medication, nicotine patches or gum, and counselling to promote smoking cessation. Further, I purpose to diagnose and investigate COPD in Florida to identify emerging threats and mobilize the public to implement distinct preventive, diagnostic, rehabilitation and support plans. The outcomes of these endeavors can be measured by the approaches mentioned above.

Conclusion

COPD is an epidemiological disease with serious health implications for the people of Florida. It has both humanistic and economic side effects. Statistics on the disease are obtained through surveys conducted by the Florida BRFSS, etc. Diagnosis and treatment of the disease follow the GOLD guidelines. Treatment for the disease involves both preventive and pharmacotherapy approaches.

PO #2: Create a caring environment for achieving quality health outcomes (Care-Focused)

The second program outcome was met in the assignment investigating chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Florida. The goal of this outcome is to teach nurses how to establish and maintain a setting that supports quality improvement. This assignment urged me to create an in-depth plan for dealing with COPD, including tools for disease surveillance, epidemiology and background information for the condition, and strategies for awareness promotion. As a result, this plan can serve as a foundation for nurses’ further research into COPD and its treatment.

AACN MSN Essential VIII: Clinical Prevention and Population Health for Improving Health

The assignment was focused on evaluating the health of the population in Florida in relation to COPD. The aims of the project were to accumulate data about COPD and its effects on the people living in the state. The details about COPD’s prevalence as well as its annual costs allowed me to see how I, as an advanced practice nurse, can address the disease’s prevention and management on a community-wide scale. As a result, I integrated the essential of population health into my skills.

NONPF Core Competency 7: Health Delivery Systems

This competency requires one to develop health care systems that acknowledge the needs of diverse populations (NONPF, 2017). The present research showed that smoking, air pollution, occupations such as coal mining, low socioeconomic status, and other factors increase the risks of people to develop COPD. Therefore, I was able to highlight the needs of specific groups and their increased exposure to the dangers of this condition.

Concepts and Reflection

Disease prevalence is the first identified concept – it is the percentage of people who have a condition in comparison to the whole population (De Nicola & Zoccali, 2015). Prevalence is related to population health research in that it helps one determine how pressing is the issue (disease). The specific prevalence rates in different communities also demonstrate which characteristics may be connected to people acquiring the condition. In this case, the prevalence of tobacco smokers among people diagnosed with COPD is apparent, and one can note a link between these aspects.

The second concept is community resources, sources of education for residents about the hazards of a particular condition (Hagan, Schmidt, Ackison, Murphy, & Jones, 2017). These resources are meant to raise awareness about the condition and improve population health by aiming to disseminate pertinent information about prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and lifestyle changes. Nurses create materials for communities, using simple language and EBP information to ensure high levels of understanding and adherence.

The examination of COPD among residents of Florida assisted me in understanding how population health is evaluated. I obtained statistics about the state’s communities and saw that some groups were more vulnerable than others, finding several risk factors that should be addressed. As an outcome, I approached the health of patients on from an individual but a group perspective, finding strategies for systemic change and organizational improvement. I also saw how interprofessional collaboration could be used to manage the health of many people at once. Data collection, patient education, transition between different health care delivery mechanisms require medical professionals to work together to raise awareness and cover all aspects of people’s lives.

Exemplar # 4: NR 510 Leadership and Role of the APN

APN Professional Development Plan

Advanced practice nurse (APN) is a position characterized by one’s independence, leadership skills, and professionalism. Nurse practitioners in Florida are certified to perform a variety of activities, including patients’ assessment, treatment, and drug prescription. To apply for a job in the field of AP nursing, one has to evaluate the regulations and guidelines of the state, in which the APN is planning to work. One should assess his or her qualities and skills to establish the level of experience and readiness for the job. Finally, it is vital for students and recently graduated nurses to learn various networking strategies and marketing techniques which can help find a suitable job and impress the employer before, during, and after the interview. This paper analyzes the scope of practice for the APN in the state of Florida, provides a personal assessment of the author based on the Benner’s Self-Assessment Tool, includes an example of a possible Curriculum Vitae (CV), and discusses some networking and marketing techniques for successful employment.

APN Scope of Practice

Florida’s regulations allow APNs to perform a broad range of activities. Sastre‐Fullana, Pedro‐Gómez, Bennasar‐Veny, Serrano‐Gallardo, and Morales‐Asencio (2014) note that the level of autonomy of APNs has greatly increased over the years. However, some practices remain unavailable or limited for nurses in Florida. The scope of practice for APNs is outlined in the Nurse Practice Act of the state. APNs can administer and dispense drugs and controlled substances, if they possess necessary training related to the area of expertise. HB 423 ARNP/PA Controlled Substance Prescribing bill authorizes physician assistants and advanced registered nurse practitioners to prescribe controlled substances under current supervisor standards for PAs and protocols for ARNPs beginning January 1, 2017 (Florida Board of Nursing, 2018).

Under the bill, an ARNP’s and PA’s prescribing privileges for controlled substances listed in Schedule II are limited to a seven-day supply and do not include the prescribing of psychotropic medications for children under 18 years of age, unless prescribed by an ARNP who is a psychiatric nurse. Prescribing privileges may also be limited by the controlled substance formularies that impose additional limitations on PA or ARNP prescribing priveleges for specific medications. An ARNP or PA may not prescribe controlled substances in a pain management clinic (Florida Board of Nursing, 2018). APNs can also choose and start specific therapies for patients, order labs and medication and diagnose and treat medical condition. However, it is vital to remember that all procedures of an APN should be recorded in a special supervisory protocol, which should be available to the department upon request.

APNs also have different specialties which further expand their scope of practice. For example, certified registered nurse anesthetists may perform anesthetic services and order various diagnostic procedures and preanesthetic medication, participate in preanesthesia care, and treat them during postanesthesia recovery (Florida Board of Nursing, 2018). Certified nurse midwives have a different set of available activities, which are also covered by the Nurse Practice Act. The healthcare facility at which these specialists work should have an established protocol for procedures that midwives can perform. For instance, some minor surgical procedures and management of obstetrical patients are possible for these nurses. Furthermore, a psychiatric nurse can prescribe psychotropic substances for treating patients with mental disorders. All in all, the actions of an APN should all be outlined in a protocol with a managing physician, who supervises the practice of nurses.

Personal Assessment

The significance of personal evaluation in the process of entering the job market cannot be overstated. It is clear that nursing students need to have a set of professional skills to succeed in their search for a suitable position. However, one’s training is not the only part that should be accounted for before applying for opened positions. Nurses should understand their level of preparedness and expertise in various areas of this profession. For example, the Benner’s Model views self-assessment as a range of experiences in different situations that can happen in the workplace (Lima, Newall, Kinney, Jordan, & Hamilton, 2014). One’s competence is also related to confidence, preparedness, and understating of self.

Self-assessment can include different categories of preparedness and one’s thoughts about the future. According to Lima et al. (2014), the competence of graduate nurses is hard to measure due to the lack of work experience. While most students usually work while receiving their education, their current experiences differ from their future occupation. Barnes (2015) points out that such a transition between roles complicates the process of self-assessment and often yields misleading results.

First of all, it is necessary to ask oneself, which career elements seem the most valuable and appealing to the nurse (DeNisco & Barker, 2015). For instance, I would like to focus on progressive adult care as I already possess significant knowledge about telemetry care, emergency departments, and acute care. I feel comfortable and confident in my experiences in this area of work. Therefore, it seems significant to me to progress by learning more about these spheres of care. Second, one should assess his or her expectations of the new position. I look forward to having more autonomy over my actions and being able to participate in patient care more actively.

The occupation of an APN can open new possibilities for long-term commitments and goals. However, I am also nervous about assuming a role with more responsibilities. Currently, one of my weaknesses is the inability to manage my time. While my experience with acutely ill patients gives me an advantage in the situation of emergency, my new position may pose challenges that could be hard to overcome. Thus, my main weakness should be addressed for me to succeed at the job.

Furthermore, one should discuss some ways to deal with stress. For example, I cope with excessive stress by trying to look at the complicated situation from a different angle. By distancing myself from the initiators of stress and perceiving the problem from a different point of view, it becomes easier for me to search for the source of the negativity. Finding the stressor can greatly reduce its impact. Taking some time to relax is also essential in dealing with stress. Finally, communicating your feelings to other people and finding support in them are also viable techniques for coping with stressful situations.

By analyzing past experiences and existing skills, one can establish the level of competence for the current or future position. My work has given me the opportunity to test my abilities and improve my understanding of the profession. While the role of an APN will be new for me, my knowledge of the practice setting and extensive experience in a particular sphere of patient care make me a proficient nurse. I would place myself on the fourth stage of the Banner’s Model, as I still have many opportunities for growth.

Networking and Marketing Strategies

Job searching may become difficult for nurses who are not used to their new level of training. It is hard to realize one’s preparedness for new tasks. Moreover, one may feel as though he or she does not possess enough information about the details of finding a good job. While the role of nursing is said to become more significant in the future, ANPs can still struggle to find a position that will allow them to implement the full scope of acquired knowledge. Employment opportunities may seem scarce for individuals who do not know how to research their local job market.

It is crucial to remember that many vacancies are not published online or in print sources (DeNisco & Barker, 2015). Therefore, people get access to these open positions through referrals and connections. In this case, networking can significantly improve one’s chances of finding a suitable job opening. Nurses should engage with their local community of peers and other medical workers to acquire insight about other organizations. Professional memberships can also contribute to one’s networking, as they provide one with more information about the state of the job market. Nurses need to stay in touch with their professional contacts to maintain the relationships. Engaging in conversations and inviting people to casual and formal meetings can open vacancies that are not published elsewhere. For instance, one can start a discussion about a new study and encourage other persons to participate. Communication can happen both online and in real life.

National and local organizations encourage networking and provide their members with better opportunities for employment. For example, the AANP Job Center (2018) is an initiative of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, which allows employers and future employees to communicate through their website. The description of vacancies on this website reveals some marketing techniques. For example, many hospitals highlight their location, describing the local landscape. Many employers discuss the high standard of living for the residents and offer various non-financial benefits to the future employees. It is possible that these strategies are meant to entice nurses to choose their job not only for the position but also for the community and location.

Conclusion

To create a viable APN professional development plan, one should acquire information about different areas of his or her future career. First of all, knowing the scope of practice is crucial as it provides one with an outlook of the future responsibilities. APNs in Florida work according to the Nurse Practice Act, which explains their duties and responsibilities. Florida has a restricted practice for nurse practitioners. One’s assessment is also essential in developing a plan for the future. In my opinion, my knowledge and range of occupations make me a competent nurse. My Curriculum Vitae showcases my skills. However, my experiences are not enough to find a successful job. It requires communication and collaboration with others. Organizations often promote networking to connect students, employees, and employers.

Curriculum Vitae (CV)

- Name: Liza R Byatt

- Home Address: 2501 Sunny Creek Dr, Fleming Island, Florida 32003

- Phone: 904-424-3744

- Email Address: [email protected]

Education

Bachelor of Science in Nursing

1995

Laguna College of Nursing

San Pablo City, Philippines

Professional Employment

2005-present

Orange Park Medical Center (Orange Park, Florida)

Staff Nurse, Relief Charge Nurse, Preceptor, Medical/Surgical Telemetry Nurse

Description: Support for patients in critical condition, monitoring of patients’ vitals and overall condition, education of other nurses based on the past experiences, administrative support.

Al Adan Hospital (Kuwait)

Staff Nurse in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU)

Description: Care for prematurely born infants and newborns with possible medical complications.

Los Banos Doctors Hospital (Los Banos, Philippines)

Staff Nurse in the Emergency Department

Description: Administrative tasks, assessment of patients’ vitals and overall condition, medication administration, patient monitoring.

Licensure and Certifications

Registered Nurse in State of Florida

License No. – RN9226322

Validity – July 2018

PCCN – Progressive Care Certified Nurse

Certified by the AACN Certification Corporation

Validity – December 2019

ACLS – Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support

Certified by the American Heart Association

Validity – December 2019

Memberships

ANA – Member of the American Nurses Association

Public/Community Service

The Way Free Medical Clinic Inc.

Nonprofit organization providing free healthcare for the uninsured residents of Clay County Florida.

PO #3: Engage in lifelong personal and professional growth through reflective practice and appreciation of cultural diversity (Cultural Humility)

The advanced practice nurse (APN) professional development plan contributed to my skills of self-reflection and interpersonal communication. This outcome was achieved as I created a plan for my future and evaluated my current abilities, knowledge, and experience as a nurse. I acknowledged my weaknesses, such as my fear of growing responsibilities, and highlighted my strengths, including my vast practice experience and preparedness for stressful situations.

AACN MSN Essential VII: Interprofessional Collaboration for Improving Patient and Population Health Outcomes

This essential became a part of my education since I understood the role of interprofessional collaboration for personal growth and patient health. My skills are not only a personal asset but also a contribution to a bigger system of medical expertise, and team work and communication lie at the basis of creating environments for increase care quality. Thus, my individual plan recognized the importance of establishing strong relations with other members for my achievements as well as the future of health care.

NONPF Core Competency 2: Leadership

I met the objectives of this competency by acknowledging that reflective thinking is one of the ways to improve one’s personal and professional qualities. I also voiced my opinion on the current state of the job market and the necessity of contributing to professional organizations. I showed that participation in interprofessional collaboration required initiative and could help individuals and the sphere of health care as a whole.

Concepts and Reflection

Scope of practice is the set of responsibilities, actions, and procedures that a health care professional (such as an APN) can have or perform. The scope is determined by state license standards and is regulated by national organizations. In Florida, APNs work under the Nurse Practice Act, and this document defines the duties of each nurse. The practice’s restrictions in this state are vital in the discussion of my professional plan because they determine my future opportunities and training aims.

Collaboration is an important concept in nursing practice that influences patients, professionals, and the system as well. It is a meaningful interaction among health care providers that implies information exchange, experience sharing, and contribution to care delivery. Collaboration is also beneficial for job searching, systemic change, and self-improvement. Nurses who engage in team work and networking can reach out to other medical professionals, creating channels for knowledge dissemination.

The creation of my professional development plan helped me to engage in self-reflection and consider my future path in health care. I realized that I had some weak points that had to be addressed. I also saw which strengths I could use in my practice. By analyzing the scope of practice for APNs in Florida, I appraised the responsibilities and problems that I might face. Furthermore, I chose progressive adult care as the focus of my education and practice since I already possessed significant knowledge in this area. This assignment revealed my leadership competencies and underlined the role of collaboration in nursing. I used self-reflection as a tool for personal and professional improvement, connecting the knowledge about myself to the objectives and characteristics of the current practice standards.

Exemplar # 5: NR 507 Advanced Pathophysiology

Discussion

A five-month-old Caucasian female is brought into the clinic as the parent indicates that she has been having ongoing foul-smelling, greasy diarrhea. She seems to be small for her age and a bit sickly but, her parent’s state that she has a huge appetite. Upon examination you find that the patient is wheezing and you observe her coughing. After an extensive physical exam and work-up, the patient is diagnosed with cystic fibrosis.

What is the etiology of cystic fibrosis?

Cystic Fibrosis (CF) – An inherited autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene. CFTR gene is located on chromosome 7 and regulates the hydration of epithelial cells throughout the body by controlling chloride and sodium transport. Katkin (2017) states that there are more than 1,900 possible gene defects that are further divided into six classes with differing severity with classes one through three being more severe and classes four through six being found with milder pulmonary diseases. The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (2018) state CF is attributable to 90% of all childhood pancreatic diseases and can affect other organs, but the most common cause of death is related to lung disease. CF affects 1 in 3,000 Caucasians, 1 in 9,200 Hispanics, 1 in 10,900 Native Americans, 1 in 15,000 African Americans, and 1 in 30,000 Asian Americans (Katkin, 2017). The mean survival rate of CF is 40 years of age (Van Biervliet et al., 2016).

Describe in detail the pathophysiological process of cystic fibrosis

The “cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTCR or CFTR) gene mutation results in the abnormal expression of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator protein, which is a cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-activated chloride channel present on the surface of many types of epithelial cells including those lining the airways, bile ducts, the pancreas, sweat ducts, and the vas deferens” (McCance et al., 2014, p. 1311). Abnormalities with the transportation of electrolytes across the cell membrane, affects the secretion of chloride and sodium in the sweat and abnormal thick secretions in the lungs, pancreas, and reproductive organs (Lawton & Schub, 2015).

McCance et al. (2014) also state the goblet cells and submucosal glands which are the mucus-secreting airway cells and increased in size and number and that an increased chloride excretion and sodium absorption bring about dehydration of the airway mucus that enhances the thick mucus that adheres to the epithelium making it hard to cough up the secretions and thusly encourages growth of bacteria. McCance et al. (2014) also report inflammation as evident by increased amount of IL-1 and Il-8 and state long-term damage is done to the respiratory system due to substantial amounts of neutrophils releasing oxidants like proteases which breaks down proteins like elastin and entice airway cells to produce IL-8 which attracts more neutrophils which means more inflammation and a vicious cycle. This protease also destroys IgG and components necessary for opsonization and phagocytosis and stimulates the mucus cells to make more mucus (McCance et al., 2014). Every individual has two CF genes called the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) and that person must receive two copies of the CFTR mutated gene to have CF (CCF, n.d.).

Identify hallmark signs identified from the physical exam and symptoms

The patient is 5 months old (the median age at diagnosis is 6 months), is experiencing greasy, foul-smelling diarrhea, poor weight gain even though there is a good appetite, coughing, and wheezing, which are classic symptoms of CF. Patients may also display a variety of symptoms from salty-tasting skin, dyspnea, clubbing, and stools can range from greasy to difficulty in having bowel movements (CFF, n.d.).

Describe the pathophysiology of complications of cystic fibrosis

Most commonly the CF genetic mistake is the DF508 protein that results in hypochloremia that progresses to lung issues related to thick mucus which inhibits proper air exchange that leads to infections, lung damage, and ultimately respiratory failure (CFF, n.d.). The CFF (n.d.) state CF is attributable to 90% of all childhood pancreatic diseases and can affect other organs, but the most common cause of death is related to lung disease. CFF (n.d.) state the malnutrition and poor growth issues with CF patients are due to the mucus build up in the pancreas that interferes with food and nutrient absorption; therefore, treatment is aimed at therapy to clear airways, and pancreatic enzyme supplements to improve absorption of nutrients. There is also a high risk of chronic endobronchial infection with children. Bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia are prone to colonize in the lung which makes antibiotics difficult to reach them. Chronic problems related to CF include; bacterial infections in the lungs, obstructive pulmonary disease due to decreased mucocillary clearance, malnutrition from pancreatic insufficiency and failure to thrive.

What teaching related to her diagnosis would you provide the parents?

Cystic fibrosis treatment and teaching depends on the stage of the disease. I will advise the parents the importance of breathing exercises, percussion and postural drainage techniques. I will also review the need to avoid known respiratory irritants such as smoke and air pollutants and persons with upper respiratory infections. The child may have trouble breathing when she lies flat, so I will instruct the mother to elevate the child’s head when she sleeps and use a cool mist humidifier to increase air moisture in the home. This may make it easier for the child to breathe and to cough up mucus. An enriched diet with vitamin and enzyme replacement to help maintain body weight will be added to her plan of care. And as far as medication, I will encourage the parents to continue giving the Antibiotics to treat and prevent lung infections and medicines to thin the mucus.

PO #1: Provide high quality, safe, patient-centered care grounded in holistic health principles (Holistic Health & Patient-Centered Care)

The first Chamberlain program outcome is concerned with nurses’ ability to engage in patient-centered care. The assignment discussing the case of cystic fibrosis gave me an opportunity to examine the condition and provide the patient’s parents with knowledge about the diagnosis. Thus, I focused on the information that is important to them and their child, informing them about possible treatments and ways to alleviate the patient’s pain and discomfort. The holistic care approach urged me to address the patient’s specific needs, especially her young age which complicated the diagnosis and treatment processes. Thus, I addressed the parents and described the signs of cystic fibrosis that could be understood without the patient’s contribution (which could be helpful in adult patient situations).

AACN MSN Essential IX: Master’s-Level Nursing Practice

To meet the ninth essential of Masters-level practice, I aimed to employ my knowledge in practice for this assignment. I considered my experience with cystic fibrosis cases as well as available theoretical information to come to the diagnosis. Then, I researched the ways in which the most vital information should be delivered to the parents. The ability to understand how patients may interpret information is a part of Masters-level nursing skills. Indirect care components included m research about the signs of cystic fibrosis and the review of the condition’s pathophysiology. Direct care in this assignment was performed through patient and caretaker education. My understanding of nursing, relevant sciences, and communication strategies assisted me in completing this assignment.

Concepts and Reflection

Teaching is a combination of facts, practices, and approaches that APNs often need to relay to patients or their caretakers to ensure their understanding of an issue. Nurses often teach patients and their relatives to recognize the signs of worsening, treat symptoms, or prevent complications. Teaching may include general tips for a lifestyle change, ways to take medications, diet suggestions, and other strategies to improve one’s health.