Abstract

This paper is an integrative review regarding the education and training requirements of critical care providers during pandemic outbreaks. It shows that different jurisdictions have different education requirements for critical care providers to work as such. However, training requirements are universal and cover five key areas – emergency planning, using critical care equipment, staff communication, infection control, and resource allocation. A cross analysis of these themes reveals that hospital administrators have the greatest responsibility of making sure that their employees work well to improve the quality of services offered during pandemics.

Introduction

Education and training are important requirements for many professions and critical care nursing is no exception (Aschenbrenner, 2009). For example, before health facilities allow health workers to work as critical care health providers, they require them to have at least basic training in critical care service provision (Palazzo, 2001). The educational and training requirements for critical care providers are higher than other health sectors (McGonagle, 2007). Without proper training, it would be difficult for critical care providers to manage such pressures. For purposes of this paper, education requirements refer to the academic requirements of critical care health providers. Comparatively, training programs refer to the informal and formal aspects of critical care health provision. This training involves clinical skills and the overall systems level management of patients (patient treatment processes and quarantine processes). The educational and training needs of critical care providers often evolve in response to current health service needs and one of these is a response to pandemic outbreaks. Recently, the world has experienced SARS, H1N1, and Ebola (among others) and caring for patients with these illnesses requires specialist training.

The intent of this paper is to explore the existing evidence relating to the educational preparation of critical care nurses involved in a pandemic outbreak. Key issues that this paper investigates include educational and training programs required of critical health providers. Therefore, the goal of this paper is to identify the educational level of critical care personnel and improve their preparedness when managing such pandemic outbreaks. This knowledge should also improve the competence of critical care providers to manage mass casualties and improve their capacities to manage the health needs that may occur in similar large-scale health disasters. For purposes of this review, health care systems comprise of an integrated system that includes outpatient, inpatient, and critical care units.

Background

What is Critical Care?

A critical situation emerges when a health care facility is overwhelmed with a huge population of infected people. Usually such patients need immediate care, without which they could die (Farrar, 2010). Based on the urgency of this need, medical facilities often overstretch their capacities to meet this demand. Therefore, the critical situation is the equilibrium between the demand and supply of health care services, as would emerge in a pandemic (Payne & Rushton, 2007). The critical care unit (Intensive Care Unit) is the main department where patients receive critical care services. It provides life support to people who may have a life-threatening condition, disease, or organ failure (Farrar, 2010). Patients who may be suffering from reversible, or potentially reversible organ failure, may also benefit from critical care services offered in the ICU. This unit also provides critical support for the victims’ family by using specialised care from specialised critical caregivers and hospital staff. Therefore, these critical care skills are usually concentrated in the critical care unit. To make sure all patients receive the best care, Martin et al. (2013) say health care facilities should have policies for admitting and discharging patients from the ICU. Protocols for admitting and transferring patients should also be available.

What is a Pandemic?

There are many informal definitions of a pandemic. However, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2015) says the internationally recognised definition of a pandemic is “an epidemic occurring worldwide, or over a very wide area, crossing international boundaries and usually affecting many people” (p. 1). Therefore, pandemics occur through the spread of infectious diseases across large populations of people who are not immune to the diseases. The scope of a pandemic could be worldwide or regional (Payne & Rushton, 2007). Examples of past pandemics, that have received global attention, include the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), the 2007 H1N1 pandemic, and the 2014/2015 Ebola crisis in West Africa. Here, it is important to understand that some diseases that have a widespread impact, such as cholera and HIV, are also pandemics (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2015).

The severity of a disease does not contribute to the definition of a pandemic because some pandemics have a higher severity than others do. The severity could vary at individual or community levels. Broadly, when understanding the definition of a pandemic, it is crucial to know the guidelines for the World Health Organization (WHO) regarding what constitutes a pandemic. These guidelines include the ability to infect human beings, the ability to cause diseases to human beings, and the ability to spread from one human to another (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2015). These are characteristics of a pandemic. Nonetheless, it is difficult to know when a pandemic may affect us. Similarly, it is difficult to know its severity. This is why this paper explores one aspect of pandemic care planning – the education and training requirements of critical care providers.

Rationale for a Review of this Topic

The primary goal of understanding the educational preparedness of critical care providers is to improve their readiness to manage emergencies when pandemics occur. Similarly, having qualified and educated caregivers would help to improve the quality of critical care services if a pandemic occurs. The same proactive measure would help to reduce the rates of death, or hospitalization, if a pandemic occurs (Martin et al., 2013). In the same way, educated and qualified caregivers could reduce the economic and social impact of a pandemic and maintain the critical role of the critical care facility when an outbreak occurs (Payne & Rushton, 2007). Lastly, the knowledge derived from this study could also be useful in preparing, educating and training other health care service providers in other hospital departments. This way, there would be a strong education and training framework for developing contingency plans when a pandemic (or communicable disease) occurs in a hospital (Payne & Rushton, 2007; Martin et al., 2013).

Research Aim

To identify the educational level and training requirements of critical care personnel concerning the preparation of pandemic outbreaks

Introduction

In this paper, I chose to use the integrative review because it shows research gaps in the identified topic area. Furthermore, it shows significant strengths and weaknesses associated with existing research studies. The integrative review consisted of five steps – identifying the research problem, data collection, data evaluation, data analysis, and data interpretation. The integrative review differs from other types of reviews because it has less focus on the quality of the research and emphasizes more on identifying research gaps. This way, it is easier to develop new ways to bridge between related areas of work. A systematic review would not provide these advantages because it may not be able to combine studies and have a holistic understanding of the research issue. Furthermore, this review is time-consuming.

Key Words and Proposed Search Strategy

To come up with a holistic understanding of the research topic, this study comprises of an integrative research review that includes both experimental and non-experimental findings. The review was systematic to make sure that the study contained credible information. Indeed, considering the vast volumes of research information surrounding the education requirements of critical care providers, this paper only included information that was relevant to the scope of the study. The Nursing Centre, CINHAL, Medline, Pubmed, and the American Journal of Nursing databases were the main sources of articles used in this study. The first stage of the data analysis process was a limited review of literature to understand the relevancy of potential information sources for the study. The literature obtained (this way) was limited to current and past English-based studies. To get correct and relevant information from the database, the search only included articles published in the last 20 years. This period is ideal for this study because most pandemics have occurred during this period. This exclusion criterion was adequate to provide a vast array of information within a relevant period (the last two decades). The key words were relevant to the scope of the analysis (education and training requirements required of critical care providers). They included “pandemics,” “disease outbreaks,” “public health,” “preparedness,” “nursing education,” “critical care” and “disaster.” The following table outlines the keywords, databases and number of articles derived from each database

Table 1: Keywords, Databases, and number of articles derived from each database

Since the scope of this study was not only limited to understanding the education and training requirements in the nursing practice, searching health management literatures also helped to expand the scope of the review. Using this strategy helped to reveal vast volumes of literature, but the inclusion and exclusion criteria mentioned in this section helped to provide the most relevant materials for this study.

Literature Review Findings

The integrative research provided several articles for review. These articles included research studies and non-research papers (editorials and opinion reports). However, getting the most relevant and credible literature for answering the research questions required the creation of an inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion and exclusion criteria appear below

Table 2: Exclusion and Exclusion Criteria

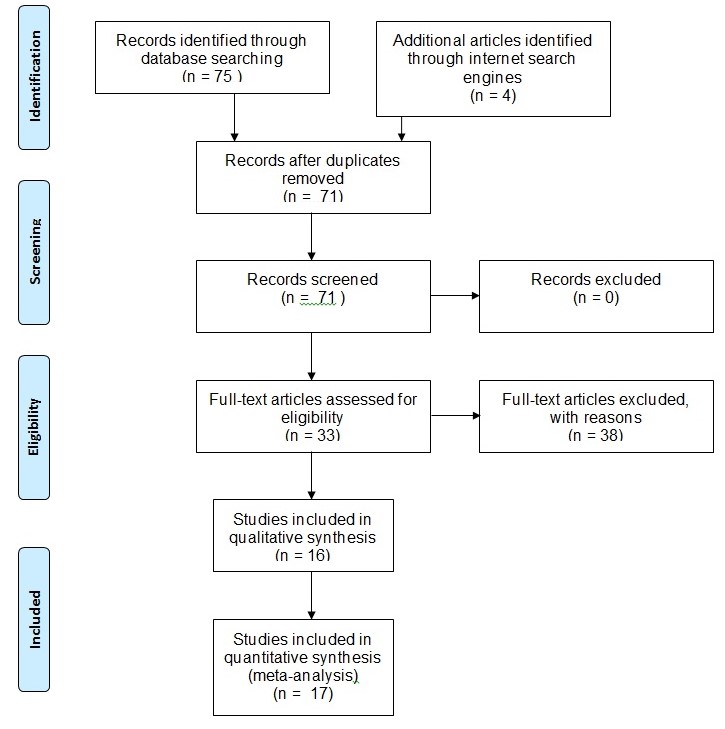

Based on the above inclusion and exclusion criteria, the literature search strategy provided 75 articles from the database search, and four articles from independent internet search engines. The initial screening criteria reviewed the articles based on their titles. This strategy reduced the number of articles to 66 accessible articles and five articles that only availed their abstracts to readers. After identifying articles that had relevant titles, the next step of the screening process involved reading abstracts of the articles and making sure that the contents of the articles contributed to the study focus. This process showed that some articles had the same contents (duplication). Such articles did not form part of the review. Consequently, there were only 71 articles available for review. The next step of the review process categorised these papers into two groups – full research studies and non-research papers. At the end of this process, there were 60 full articles and 11 non-research articles. This process paved the way to analyse the articles based on their contribution to the research topic. Here, I excluded articles that did not focus on pandemics or the education requirements for critical care providers. I did not read them in full. The remaining articles were either qualitative, quantitative or mixed studies. The research review process ended after this screening stage because the available articles were relevant and credible for use in the paper. The flowchart below shows the steps and the outcome of this process

The study used a thematic analysis to compare the findings of the above-mentioned articles. Each theme had a unique code for analysis. I chose the coding because there was a lot of information retrieved from the 75 articles sampled and I had to narrow them down to focused issues that helped to answer the research questions. The coding technique helped to do so. Here, the codes symbolised consistent themes in the analysis – education, training, and technology. To come up with these themes, I read the contents of the study to understand how they contributed to the study questions. The title of the studies helped to highlight the context of the paper and its contribution to the research questions. For example, I grouped papers that discussed the certification requirements of critical care nurses into one theme – education. I included others that discussed practical skills in the critical care unit into the “training” theme. A description of these studies appears below

Description of the Studies

Topic Description

The selected papers for this study did not openly address issues that highlighted the educational requirements of critical care providers when handling pandemic outbreaks in critical care settings. For example, some of the articles only focused on the educational requirements for critical care providers, while others focused on the training or certification requirements of critical care providers. Consequently, there was a need to analyse the articles in relevant sections.

Description of Study Concepts and the views included

Based on the difficulty associated with finding relevant themes, it was pertinent to review the relevant studies and find the hidden meaning of critical care and pandemics. Most of the articles explained the meaning of the concept from the policy makers and health administrators’ viewpoints. Albeit relevant to the scope of the study, few of them analysed the same issue from the caregivers’ views and the views of health agencies. However, the views of nursing managers were evident in some of the papers (albeit still from an administrative perspective). The following table shows authors, year of publication, study designs, titles, perspectives, and themes of all the articles used in this review

Table 3: Authors, year of publication, study designs, titles, perspectives, and themes of all the articles used in this review

Quality of Identified Studies

Evaluating the sources of information for research studies is important in evaluating the quality of information obtained from such studies. According to Jackobson (2009), there is no standard measure for assessing the quality of studies used in an integrative review. The lack of standards comes from the lack of a proper criterion for defining quality. In this analysis, it was pertinent to adopt an integrative review of the literatures sampled. To do so, this paper used a historical and antecedent search approach for undertaking the study. Research authenticity, information value, and methodological quality were important considerations that informed the research process. Whittemore and Knafl (2005) support the use of these criteria to evaluate the quality of research articles. This paper’s findings are credible because they are products of information retrieved from credible and well-authenticated databases. Similarly, in this paper, I reviewed the abstracts of each study included in the review to make sure that the information obtained was relevant to the study focus. Thus, this paper’s findings are credible because they come from authenticated sources of information and focus on the scope of review.

Summary

This section of the paper has described the methodological approaches undertaken to come up with the findings of this paper. It has described how the first search strategy revealed many studies and later narrowed them down to relevant articles, based on detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in this paper. Undoubtedly, many of the studies selected for review in this paper contributed to understanding the educational or training requirements for critical care service providers. Their differences and varied contexts were useful for this review because they introduced different dynamics of the study focus to this review. Particularly, they introduced different perceptions of understanding the education and training requirements needed of critical care service providers when managing pandemic outbreaks. This contribution was useful in providing information in areas where there was inadequate information about the education, training, or certification requirements of critical care providers when handling pandemic outbreaks. Therefore, the literature reviewed in this paper explores many dynamics of the educational background needed of critical care service providers in the critical care setting.

Discussion

Education

An initial overview of the literatures sampled in the paper revealed that critical care education should equip critical care service providers with the biological and physiological knowledge required to manage pandemic outbreaks. To meet this goal, this paper found out that education programs emphasise the need for critical care providers to have proper academic qualifications and meet certification requirements. The following section of this report delves into these details

Academic Qualifications

Webb et al. (2009) argues that undergraduate nurses are the main source of critical care providers during a pandemic. Most of the shortfall for health care workers occurs in the critical care unit. It takes about four years to train a competent critical care nurse (Webb et al., 2009). This means that a change in the number of undergraduate nurses cannot affect the staffing requirements in the critical care unit until four years have passed. For example, during the early 2000s, there was an acute staffing shortage of critical care nurses in Australia because of a reduction in the number of critical care nurses during the late 1990s (Webb et al., 2009). Since 1998, Australia has witnessed an increase in the number of undergraduate nurses, which has in turn increased the number of critical care nurses (Webb et al., 2009). However, Webb et al. (2009) cautions that the available data for the number of people who have completed undergraduate courses and are available to work as critical care nurses may be inaccurate because of inconsistencies in data reporting procedures. For example, they say, “Accurately determining numbers of students commencing and completing postgraduate critical care courses via the university sector is difficult, due to the inconsistent nomenclature, generic nomenclature and inadequate processes for universities to report to DEST” (Webb et al., 2009, p. 44).

Academic requirements are essential for critical care nurses because they are required to have a Bachelor’s degree in nursing or an associated degree (Tegtmeyer et al., 2011). Furthermore, they are required to have passed associated examinations, such as the National Council Licensure Examination (Tegtmeyer et al., 2011). This examination would allow critical care workers to work as such. In Australia, nurses could work as critical care service providers without necessarily having a post-graduate qualification that certifies them to work as such (Webb et al. 2009). In fact, many nurses seek higher qualifications when they are already working as critical care nurses. Minimum standards stipulate that at least 50% of all critical care nurses should be qualified to work as critical caregivers (Webb et al., 2009). However, ideally, this number should be 75% (Webb et al., 2009). Higher institutions of learning offer formal education for critical care providers in Australia. Selected hospitals and the NSW are other institutions that offer the same course (Webb et al., 2009). Usually, students may access courses in critical care service provision in institutions that are outside their states. Available distance module courses supplement this privilege (Webb et al., 2009).

Many literatures sampled in this paper revealed that academic education not only prepares health workers to improve their craft, but also improve the quality of interactions they have with victims of pandemics and their families. For example, an article by Veenema and Toke (2007) revealed that critical caregivers should understand the strain and anxiety that may come when a pandemic outbreak occurs in the critical care environment. In this regard, health care providers need to recognise the dynamic needs of such groups and know that some of their feelings may present significant obstacles for managing pandemic outbreaks (Kumar et al., 2009). A critical care nurse who has received proper education regarding how to manage pandemics in the critical care setting could be an invaluable resource in spearheading health management efforts when such health disasters occur (Nap et al., 2008). Furthermore, such health workers could be instrumental in identifying the needs of patients and family members, during pandemics, thereby providing customised care (Webb et al., 2009). It is possible to realise positive health outcomes in this regard if patient care continuity is a priority for critical care providers. Similarly, it is possible to realise these outcomes if the critical care providers are part of the nursing team.

Certification

Critical care service providers are required to have varied certification levels before they work in the critical care unit. These certifications are important when providing different types of care including progressive care and cardiac care (among other types of care) (Tegtmeyer et al., 2011). Different countries have unique certification levels of training health workers in the critical care service delivery. For example, AACN certification is an important requirement for critical care nurses in America (Tegtmeyer et al., 2011). However, getting these certifications does not mean that the nurses get additional practice privileges in the critical care setting because the nursing boards are the main bodies mandated to offer additional practice privileges (Tegtmeyer et al., 2011). Occasionally, some health care facilities do not require critical care service providers to have these certifications because few professionals do. Furthermore, getting these certifications requires nurses to have extensive knowledge of different aspects of care provision, including pathophysiology and critical care practices (Tegtmeyer et al., 2011). Although it is difficult to get these certifications, people that have them get a lot of respect for their work (Tegtmeyer et al., 2011). Those seeking similar certifications also get respect for their quest to improve their academic and professional skills in the critical care setting (Nap, Andriessen, Meessen, Miranda, & Van der Werf, 2008). In line with the rich history of nursing in taking care of the needs of patients and family members during periods of health crisis, these health care professionals have a unique opportunity to highlight their skills and expertise for managing critical care issues that may emerge from a pandemic.

Training

To make sure the above-mentioned education programs meet their intended purpose, the sampled literature revealed that critical care service providers should participate in drills (training) to evaluate their preparedness in managing pandemics. As, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (2007) says, critical care nurses often have to undergo proper training before they are allowed to operate in the critical care unit. Different jurisdictions have unique sets of training standards for their nurses. For example, American nurses have to undergo training through the American Association of Critical Care Nurses (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2007). Australian nurses have to undergo similar training from the Australian College of Critical Care Nurses (Webb et al., 2009). Before these professions get the certificate for critical care nurses, they need to train in several areas of critical care nursing, including planning for pandemics, staff communication, infection control, resource allocation, and using critical care equipments. The following subsections of this report highlight what most researchers have said about these key training areas.

Using Critical Care Equipments

Palazzo (2001) says that employing new technology and advanced health resources is a critical component of providing adequate training and education to critical caregivers. These tools would allow critical care workers to provide customised care to pandemic victims. Technological competence is at the centre of most training programs that strive to prepare critical care nurses to work in the critical care unit. Stated differently, care providers need to learn how to operate machinery and equipment that are in the critical care unit (Palazzo, 2001). Such equipment could include hemodynamic and cardiac monitoring systems. Other equipment in the critical care setting that critical care providers need to know how to operate are ventilator machines, balloon pumps and ventricular devices (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2007). Many care providers receive training through in-house hospital training programs. However, others learn how to use such equipment through manufacturer training and by spending time with other operators who have used the materials before (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2007). A one-off training exercise is inadequate to train new workers holistically (at least in most jurisdictions) because many medical boards require critical care service providers to undergo continuous training, at least annually, about how to operate such equipment (Webb et al., 2009). Rapid technological changes that could easily make equipment obsolete necessitate this requirement. For example, many States of America require nurses to undergo annual training exercises about how to use the equipment in the critical care unit because of rapid changes in technological requirements (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2007). This goal aligns with the quest by health administrators to have their critical care providers have updated skills about how to use the new equipment. This is why many critical care nurses go to annual conferences that learn how to operate the latest medical equipment (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2007).

Planning for Pandemics

Hospitals often have a duty to plan for pandemics. Best practice dictates that all hospitals should have an active planning committee that outlines the steps to take in the facility when a pandemic occurs (Tegtmeyer et al., 2011). This committee should have a decision-making team and a command structure. Aschenbrenner (2009) says the success of the planning phase depends on proper staff training. For purposes of providing quality critical care services, many researchers sampled in this report highlighted the need for health institutions to train nurses in emergency care planning and critical care management in the high dependency unit (Farrar, 2010; Bulman, 2009). For example, Bulman (2009) emphasizes the importance of helping nurses to understand the need to record important statistics about a pandemic, when it occurs. He says, the surveillance should occur before and after the pandemic (Bulman, 2009). The surveillance would allow critical caregivers to identify vulnerable populations and those that would need critical care. Furthermore, through their disease surveillance criteria, they would know different strains that cause a pandemic (this practice is often common during influenza pandemics) (Michael et al., 2009). Based on these insights, hospitals need to have a surveillance system in place before a pandemic occurs (Michael et al., 2009). In this training regiment, health workers learn to isolate patients who may suffer from a pandemic and monitor them closely. The surveillance process is expansive and includes knowing the number of admissions and employee absenteeism rates. Using these statistics, critical care providers easily learn to formulate infection control strategies. To implement these strategies successfully, critical caregivers learn the signs and symptoms to look out for during a pandemic. For example, critical care nurses who have worked in Ebola-hit areas of West Africa have learned the haemorrhage symptoms associated with the virus. In line with this requirement, Michael et al. (2009) says, hospitals should always maintain a database of employees that could suffer from such pandemics. This step is critical because staff surveillance is important for hospitals if they want to maintain the right number of employees in the critical care unit (Michael et al., 2009). Procedures should be in place to detect cases of resurgence and the hospital’s capacity to provide vaccines, or other forms of treatment, to patients (Stephens, 2013). Broadly, critical care nurses learn that the surveillance system should include different types of monitoring programs such as syndrome surveillance and laboratory surveillance.

Communication

The complex and multidisciplinary characteristics of critical care operations make intensive care units uniquely susceptible to the spread and occurrence of pandemics (Molyneux, 2009). Poor communication within such critical care settings could potentially lead to disasters, or major incidents, in the critical care units (Amaratunga et al., 2007). Several factors could cause poor coordination and poor organisation of tasks in the critical care environment (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2007). They include poor delegation of tasks, role ambiguity, and poor shift changes. Some researchers say unavailability of a patient’s background, nurse absenteeism, and ineffective hierarchical team structures also cause poor coordination of tasks in the critical care unit (Molyneux, 2010). The loss of information is also a problem in this regard. Frequent patient movements across critical care units are also possible avenues for information loss and miscommunication in the critical care unit, thereby further leading to adverse health outcomes. This is because minimal discussions often occur when such transfers happen, thereby limiting a patient’s right to get proper and comprehensive health care services (Palazzo, 2001). Inadequate verbal communications between critical caregivers also contribute to misinformation, which stems from poor information transfers. This way, communication problems are likely to increase from such a scenario.

In this training program, critical care nurses learn that the critical care planning process should contain important information surrounding the provision of critical care during a pandemic. For example, they learn about the importance of having a crisis command structure that outlines the triggers of critical care because it provides an integrative platform for including the views of other stakeholders in the provision of critical care (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2015). The same training program emphasizes the need for these nurses to collaborate with the hospital administrators because the latter monitors the hospital emergency plan, regularly, to provide timely updates regarding the provision of critical care and communicate the need for resource diversification, or decreases in critical care services. Hospitals are also included in the training program because they make sure that there are effective triage and isolation procedures in the critical care unit, as a strategy for minimising infections (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2015). The main goal of undertaking this task is to evaluate the potential necessity of implementing crisis control measures in the critical care unit and making sure that the trained critical care providers minimise new infections (Contrada, 2013). Some hospitals recognise this need by assigning a triage coordinator to teach the critical care providers about the need to monitor the inflow and outflow of patients and staff in the critical care unit (Contrada, 2013). Their roles may also include teaching critical care staff about how to refer and defer patients in an out of the critical care unit, based on specific exclusion and inclusion criteria.

Based on the need for proper communication in the critical care unit, staff training often requires nurses to learn best practices in communication. Caregivers have different alternatives for improving communication in the critical care setting. For example, critical care providers learn that improving documentation processes during handover processes could improve coordination among health care service providers. They also learn that informing surgeons about the knowledge bases of the nurses and other critical caregivers is also important in improving health outcomes in the critical care setting (Molyneux, 2010). Critical care service providers who seek advanced training learn that the nurse manager should have an updated list of every critical caregiver working in the critical care unit. The details of every caregiver should include the following information – name, phone number, address, designation, ability to care for critical care patients, ability to care for paediatric patients, and vaccination status (Michael, Helm, & Graafeiland, 2009). The purpose of having this information is to notify the caregivers about changes in the care giving facility and to contact staff to attend the workplace.

Based on the above-mentioned dynamics, the effective operations of the critical care unit depend on effective communication among all concerned stakeholders. Jackobson (2010) says key stakeholders that should be involved in the provision of critical care include government officials, private health agencies, and media agencies. Every health care facility should have a critical care unit that integrates into the overall emergency unit. Frequent communications, within the critical care unit, are crucial in making timely decisions about public health management (Stephens, 2013). Jackobson (2010) believes that all hospitals should outsource staff training processes to outside agencies to allow the internal crisis management unit to undertake their tasks effectively. Most nursing professionals who undergo such training often become clinical spokespeople. Their primary role is informing the public about the activities of the critical care unit (Stephens, 2013). From their training programs, they learn to give accurate and timely information to all stakeholders that may be interested in knowing how the hospital is managing a pandemic in the critical care unit (Stephens, 2013). Often, such personnel should provide critical information that would be useful to this stakeholder group. Such critical information may include number of staff present, availability of vaccinations, and infection control measures (Jackobson, 2010). Through the guidance of local health authorities, such trained professionals should determine the frequency and mode of communication in the critical care facility. For example, hospitals should create effective risk communication methods and relay them to the concerned stakeholders to gain their trust and secure their cooperation when managing a pandemic. Overall, all critical care employees learn the importance of existing policies and procedures surrounding pandemic management. This requirement stems from the need to alert people about emergencies. The same system should improve coordination within the critical care facility and monitor critical care service delivery (Jackobson, 2010).

Infection Control

Trained health care service providers should ensure they observe standard infection control procedures in the critical care setting to minimise exposure and transmission of disease-causing microorganisms (Stephens, 2013). There should be no exceptions when adopting these procedures (Stephens, 2013). Often, these procedures include observing high hygiene standards and observing the proper use of medical equipment in the critical care unit (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2007). For example, most training curriculums teach prospective critical care providers about the importance of maintaining hand hygiene as a critical element of infection control. Particularly, this training requirement is important in teaching critical care nurses about how to manage influenza pandemics (Victoria, 2007). Indeed, contact with infected persons, without proper hygiene would lead to new infections. Therefore, critical care nurses learn that maintaining proper hand hygiene, before and after contact, with patients is important in preventing further re-infections. Many training curricula also teach such personnel about the need to observe safety procedures in the critical care unit to minimize the risk of droplet infections (Victoria, 2007). For example, Michael et al. (2009) say it is important for critical care providers to learn that during pandemics, isolation is critical. Ideally, during pandemics, each patient should have a room. However, because of logistical reasons, many critical care providers group their patients in one room. Critical care providers learn that when they treat patients in these rooms, they should always have surgical masks. This requirement means that they always have to wear surgical masks whenever they are close to symptomatic patients. The surgical masks are part of a wide array of personal protective equipment that the care providers need to understand how to use (Michael et al., 2009). They may include gloves, plastic apron, gown, respirators, and eye protection. Research shows that understanding how to use such equipments should help critical care providers to understand how to minimise the risk of transmission. Therefore, the proper use of these equipments is a critical part of the training program because failing to use them correctly could cause new infections (Michael et al., 2009).

Training programs also teach critical care providers about the need for understanding the role of environmental factors in the critical care service provision. Particularly, the help them learn that environmental cleaning and disinfection should occur in clinical rooms and critical care units (Payne & Rushton, 2007). This way, caregivers learn to take extra care to make sure that critical care units are clean after patients leave the unit to prevent the risk of transmission to new patients (Payne & Rushton, 2007). Alternatively, they learn that when patients are there, the critical care unit should be clean. Basic training programs help critical care providers to pay attention to frequently touched surfaces, such as door handles and medical equipment, by cleaning them daily. They also include hospital administrators by encouraging them to pay attention to cleaning staff rosters by making sure they work in designated areas because interchanging them across different areas of the medical facility could increase the risks of infection (Parry et al., 2011). Standard practice dictates that the cleaning staff should receive proper training on how to use cleaning equipment as well (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2015). This way, they would also understand the precautions to take when cleaning the critical care units. For example, they should always make sure they wear protective equipment, such as aprons, when cleaning the critical care units (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2015). When operating in isolation cohorts, they should also wear a surgical mask when cleaning (Payne & Rushton, 2007). Indeed, properly cleaning equipment is an important part of environmental infection control because it helps to sterilise and disinfect them. Basic training programs teach critical care staff about the need to avoid using equipments that increase circulation of air because of heightened infection risks. In this regard, critical care providers should avoid fans and such like equipment in the critical care unit. The critical care providers also learn about the need to remove all non-essential furniture and fittings from the critical care unit to reduce the probability of dirt concealment (Payne & Rushton, 2007). This step makes it easy for care providers to clean the unit. Overall, critical caregivers should make sure that they maintain proper hygiene in the clinical rooms. The minimum hygiene standards stipulate that health workers should clean the critical care unit daily (Victoria, 2007). Furthermore, the same process should occur every time a patient leaves the critical care unit. To realise the best results, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2015) says cleaners should receive proper education regarding how they should undertake this process. Ideally, critical caregivers should use disposable equipment when taking care of patients in the clinical room.

Isolating infected persons from the general population is also a critical part of infection control. Advanced training programs outline it as a critical step in managing pandemics because it minimises the rate of infections (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2015). To optimise critical care results, these programs highlight the need to introduce a designated area to treat critically ill patients (Bulman, 2009). Caregivers in different parts of the world have often undertaken this process. For example, to manage the Ebola crisis in West Africa, health practitioners created critical care units in isolated wards of hospital facilities to treat infected persons (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2015). Such isolation facilities should have limited access to persons (visitors, staff, and patients) because they are highly contagious zones. The limited access to such facilities also includes minimal patient transfers because infected persons often have different levels of disease severity. Advanced critical care training programs teach critical care personnel about the importance of minimising movements of persons in an out of the critical care unit (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2015). When there is a need to do so, the same program teaches the critical care staff about the need to use proper equipment and protective gear if staff, or visitors, want to gain access to the critical care unit. They also teach them about the need for isolating patients who leave the care unit to a different facility in the hospital, especially if the doctors perceive them as contagious (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2015).

Resource Allocation

Health researchers, worldwide, have recognised the immense strain on available critical care resources when a pandemic occurs (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2015; McGonagle, 2007). However, available resources are usually insufficient to provide maximum care to patients. Based on these limitations, advanced training curricula, for critical care nurses, emphasize the importance of having a common criterion for maximising the use of available resources. For example, some curricula teach nurses to adopt a standard triage algorithm to allocate available resources, based on survival needs (McGonagle, 2007). The goal is to evaluate patients and assess their need for critical care support. To come up with accurate findings, most critical care facilities teach critical care service providers to use the below-mentioned inclusion and exclusion criterion:

Based on the above exclusion and inclusion criteria, critical care providers learn that if a patient meets the criteria outlined in the inclusion section and fails to meet the same requirements in the exclusion section, the patient would be eligible to receive critical care. Nonetheless, most training curricula highlight four main components of critical care service provision – exclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, minimum requirements for inclusion, and the prioritization criteria (Contrada, 2013). The inclusion criterion identifies patients who may need ventilation support because this facility is the main differentiating factor between the critical care unit and other departments in a health care facility (especially when an influenza pandemic occurs). The exclusion criterion identifies three types of patients – patients who have experienced a poor prognosis, patients who require unavailable critical care resources, patients with a pre-existing medical condition and patients who suffer from a poor prognosis. Critical care training teaches nurses that although victims who do not meet the inclusion criteria may need critical care, the type of resources needed and the prolonged stay required by them (in the critical care facility) may not justify their admission in the critical care unit when a pandemic occurs. Often, hospital administrators exclude them from the critical care unit because of limited resources (McGonagle, 2007). Critical care providers learn that although they may have many patients in the critical care unit, they should not exceed a resource ceiling during a pandemic. Although this concept is alien to the medical field, experts have used it to provide health care services to refugees and soldiers (in wars) (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2015). The main goal of having this resource ceiling is to identify patients who may have lower chances of survival. After identification, minimum resources care providers should allocate minimum resources to their care because they could realize positive outcomes by redirecting the same resources to patients who have a high likelihood of recovery.

Overall, advanced training programs teach critical care providers about the need to adopt a streamlined admission criterion for gaining access to the critical care unit. Here, Contrada (2013) says, it may be beneficial for the hospital to adopt cross-training procedures to seek alternative help from health workers who work in other departments. The admission guidelines should triage patients to the right facilities. Ideally, this process should help critical care providers to identify new patients who need critical care. Using this criterion, critical care providers learn to cohort patients who need critical care, defer those that do not meet the inclusion criteria and defer elective admissions. During periods of moderate infections, the critical care providers could limit admissions to only those people who need hospitalisation.

Discussion

An initial overview of the literature related to this study revealed that, an unexpected pandemic could cause a rapid increase in the number of its victims within the first 2-3 month period of infection (Department of Health UK, 2012). Beyond palliative and supportive interventions, there would be minimal interventions that health care service providers could offer during the initial stages of an outbreak (Kenneth, 2007). The literature review shows that most planning programs have a “reasonable worst case scenario” derived from years of healthcare education and training in past pandemics (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2007; Farrar, 2010). In a reasonable worst-case scenario, most health care service providers assume that a pandemic could affect up to 50% of the population. These intrigues have informed the methodological approach for this study by limiting the focus of the study to two factors – education and training. Tegtmeyer, Conway, Upperman, and Kissoon (2011) say education and training would be instrumental in limiting the negative effects of a pandemic outbreak on critical caregivers. For example, they say educating and training caregivers would reduce the stress and anxiety that often affect the quality of services provided by critical care providers (Tegtmeyer et al., 2011). Staff training is an important part of critical care nursing. Ideally, it should take place before a pandemic occurs (Ma et al., 2011). All types of caregivers should undergo proper training before a pandemic occurs. This paper has identified key areas of training as emergency planning, training for equipment use, staff communication, infection control, and resource allocation. However, as the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (2007) observes, there should be adequate plans to acquaint critical caregivers about the existing arrangements surrounding contingency plans. Similarly, health administrators should know existing management arrangements to manage a pandemic. To make sure that the training process covers all these details, there should be a log that describes previously discussed issues and the time that the discussions took place. Training caregivers about critical care delivery is part of existing health agency requirements (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2007). Tegtmeyer et al. (2011) say, although the critical care setting is not ideal for educating caregivers about how to manage pandemic outbreaks; positive results could still emerge from the process.

Education and training goals during critical care service delivery should always align with the goals of critical care service providers. Furthermore, they should also align with the different needs of the selective stages of pandemic management. All training materials should be readable. General topics that could appear in the education and training program include infection control, disease prevention, resource allocation and employee communication (Jackobson, 2010). Clinic-specific topics (mostly) focus on how to offer improved critical care services to pandemic victims. Pandemic staffing contingency plans and reporting protocols are other factors that may be included in the education and training program (Michael et al., 2009). Usually, pandemics vary across three levels of severity – “mild,” “moderate,” and “severe.” In severe stages, a “just in time” training method may be needed to provide effective critical care for pandemic victims. For instance, such training may include a quick detection of pandemic patients and the identification of effective containment measures to prevent the further spread of the infection. The training may also include how to provide psychological support to patients and their families. Cross training may be essential here because the critical care unit may lack enough people to handle all duties required of the facilities. Therefore, having employees who could manage different tasks may be essential in this regard. Nonetheless, many health researchers emphasise the importance of educating critical caregivers about the importance of receiving vaccinations against known diseases that may further create a pandemic (Michael et al., 2009). Health administrators should expand the education and training programs to improve the skills of the health care workers and enable them to work beyond their primary scope of care delivery (Michael et al., 2009). The education and training program should also include programs to educate visitors (to the critical care unit) about the importance of maintaining proper hygiene and adhering to the existing policies surrounding infection control. For example, putting posters in the critical care facility is an effective way of communicating with the visitors about the need to maintain proper hygiene when visiting the critical care unit. Such education materials should also include signage in common areas that are openly accessible to visitors. They may include elevators, cafeterias, and lavatories. The flyers and educational materials should contain the epistemology of the disease-causing pathogen because most people may not be aware of its existence (Michael et al., 2009). These messages should be in multiple languages and easily comprehensible. Their format should not contravene existing guidelines about infection control (as stipulated by health authorities).

Based on the goals of the above-mentioned education and training programs, there is a need to create clinical buy-in when training workers in the critical care setting. The main goal of seeking this support is to simplify the implementation process that would allow health workers to implement what they have learned about infection control in the clinical care setting. A top-down leadership approach is important in legitimising critical care health training (Bulman, 2010). The support of health administrators is also useful in funding such programs. The commitment and involvement of unit leadership is essential during this phase because it plays an important task of motivating critical caregivers to participate in the training process (Palazzo, 2001). Furthermore, such leadership is important in creating enough time for caregivers to use what they have learned about infection control in the clinical care setting and explaining the consequences of ignoring what they have learned (Bulman, 2009). Such recommendations are applicable to nurses and physicians alike. Leaders in infection control management have realised this team “buy-in” by employing multiple strategies (Palazzo, 2001). A key strategy is engaging the nursing staff. Its subsets include identifying unit leaders and seeking their thoughts regarding infection control, involving frontline staff in executing infection control programs, and seeking the input of caregivers about disease transmission and their beliefs about its minimisation (Sprung et al., 2010). To keep employees interested in the subject, the infection control teams should also seek the input of caregivers regarding suggestions and changes that could improve infection control measures. Here, Molyneux (2010) adds that it would be more interesting for the caregivers to share their experiences about infection transmission because it would make them more interested about their roles in the infection control team.

The model of care provided by caregivers should reflect the hospital’s staff capacity and the number of patients who need critical care. To optimise their care services, many hospital facilities create a critical care team that has both experienced and inexperienced staff (Martin et al., 2013). Health administrators prefer to use this model to give critical care because it provides the best blend for supervising new/inexperienced staff, but still taking care of patients (Martin et al., 2013). However, health experts say health workers should evaluate the model (daily) to reflect the acuity needs of the facility (Palazzo, 2001). Usually, the director of intensive care and senior nurses make important decisions about varying the care-giving model. Staff deployment is usually a top priority for these professionals (Palazzo, 2001). For example, when there are excess employees in one ICU, hospital administrators move the extra health workers to another facility that supports the critical care unit. Staff redeployment often occurs through negotiations with different hospital executives. Best standards in critical care delivery stipulate that a critical care unit should have at least one experienced ICU trained carer, one senior nurse, one clinical development nurse, and one overall unit coordinator (Palazzo, 2001). The availability of skilled caregivers often determines a hospital’s capacity for extra staffing. The skilled caregivers may include nurses employed in an extra capacity at a different hospital department, qualified nursing students, experienced staff from the post-anaesthetic care unit, and qualified medical students (Palazzo, 2001).

Critical caregivers have a duty to their patients and the nursing unit. Since their services are important for the normal functioning of the critical care unit, they are supposed to inform the senior nurse if they cannot come to work so that hospital administrators make alternative arrangements to get new caregivers to undertake their duties. If authorities declare a state of emergency during a pandemic, the obligations of the critical care staff increase to show consistency with the Emergency Act (Farrar, 2010). Using protective equipment in the critical care unit is also a central role of the skilled critical caregivers. This obligation should align with the existing infection control policies of the hospital. Different health departments have developed unique monitoring and protection standards for hospital staff who are not critical caregivers. Usually, these guidelines should prepare such employees to work in the critical care setting, or offer their support in such settings. All relevant officials who supervise activities at the critical care unit should deliberate daily about how they would continue providing quality care in the hospital setting. These regular meetings should also re-evaluate staffing requirements to make sure educated and trained critical caregivers always provide quality care to their patients. There should be existing strategies for de-escalation because cases of frustration, anxiety and fatigue are often common among both skilled and unskilled critical caregivers whenever a pandemic occurs. Such issues often occur when critical caregivers operate far from home, or in areas that are alien from their ordinary work environments. Based on these insights, hospitals have a critical role to play in improving the quality of their critical care services, through critical care training and development, when managing pandemic breaks.

Conclusion

The findings of this study could guide critical care providers in controlling pandemics in the critical care environment. The main reason for having a succinct criterion for managing a pandemic outbreak is the need to have a detailed response framework for pandemic infection management in the critical care environment. Therefore, the content described in this paper could add to existing best practice because it comes from detailed scientific research and dynamic expert responses. Since most of the principles outlined in this paper, for managing pandemic outbreaks, in the care setting still apply today, the information outlined in this report could provide more details about managing pandemics through the main points raised in this discussion. Furthermore, since some of the details outlined in this report also apply to educating and training employees from other medical departments (not only the critical care environment), the findings of this review could apply to other medical departments, such as the high dependency unit.

Nonetheless, it is important to understand that a critical part of critical care delivery is compliance with infection control standards, as stipulated by global and regional health bodies. The perception that an organisation has clear policies and procedures for giving a critical care service is a critical variation of compliance procedures. The perceived attitudes and actions of hospital management regarding occupational safety issues also stand out as an important variable in adhering to education and training standards. Providing critical caregivers with useful feedback regarding existing compliance standards helps to improve their compliance with existing rules about nursing education and training. Creating a compliance unit to make sure that all facilities comply with existing rules is an effective way of increasing their awareness and compliance levels about critical care nursing and education. Overall, it is important to appreciate the role that well trained and educated critical care providers play in planning for extreme pandemics that require critical care. As highlighted in this report, critical caregivers could work on different aspects of infection control that could improve services in the critical care unit.

References

Amaratunga, C., O’Sullivan, T., Philips, K., Lemyre, L., O’Connor, E., Dow, D.,…Corneil, W. (2007). Ready Aye Ready? Support mechanisms for Healthcare

Workers in Emergency Planning: A critical Analysis of Three Hospital Emergency Plans. American Journal of Disaster medicine, 2(4), 195-210.

Aschenbrenner, D. (2009). The 2009 H1n1 Flu and Seasonal Vaccination. American Journal of Nursing, 109(12), 56-59.

Bulman, A. (2009). 100 Years of American Red Cross Nursing. American Journal of Nursing, 109(5), 32.

Bulman, A. (2010). On the Cover. American Journal of Nursing, 110(2), 25.

Contrada, E. (2013). CE Test 2.5 Hours: Predictors of Nurses’ Intentions to Work During the 2009 Influenza A (H1N1) Pandemic. American Journal of Nursing, 113(12), 42.

D’Antonio, P., & Whelan, J. (2004). Moments when Time Stood Still: Nursing in disaster. American Journal of Nursing, 104(11), 66-72.

Daugherty, E., Perl, T., Rubinson, L., Bilderback, A., & Rand, C. (2009). Survey Study of the Knowledge, Attitudes, and Expected Behaviors of Critical Care Clinicians Regarding an Influenza Pandemic. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 30(12), 1143-1149.

Department of Health UK. (2012). Health and Social Care Influenza Pandemic Preparedness and Response. Web.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. (2015). Definition of a Pandemic. Web.

Farrar, J. (2010). Guest Editorial Pandemic Influenza: Allocating Scarce Critical Care Resources. JONA: Journal of Nursing Administration, 40(1), 1-3.

Jackobson, J. (2009). School Nurses Nationwide Respond to Influenza A (H1N1) Outbreaks. American Journal of Nursing, 109(6), 19.

Jackobson, J. (2010). Lessons Learned from the 2009 H1N1 Pandemic Flu. American Journal of Nursing, 110(10), 22-23.

Johnson, V. (2009). News From NACCHO: Mass Fatality Planning for Pandemic Influenza: A Planning Model From a Seven-County Region in Kentucky. Journal of Public Health Management & Practice, 15(2), 176 – 177.

Kenneth, D. (2007). Public Health Law: Legal Preparation and Pandemic Influenza. Journal of Public Health Management & Practice, 13(3), 314-317.

Kumar, A., Zarychanski, R., Pinto, R., Cook, D., Marshall, J., Lacroix, J.,…Fowler, R. (2009). Critically Ill Patients With 2009 Influenza A (H1N1) Infection in Canada. JAMA, 302(17), 1872-1879.

Martin, D., Brown, L., & Reid, M. (2013). Predictors of Nurses’ Intentions to Work During the 2009 Influenza A (H1N1) Pandemic. American Journal of Nursing, 113(12), 24-31.

Ma, X, He, Z., Wang, Y., Jiang, L., Xu, Y., Qian, C.,…Du, B. (2011). Knowledge and attitudes of healthcare workers in Chinese intensive care units regarding 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic. BMC Infectious Diseases, 11(24), 1-7.

McGonagle, M. (2007). VNAA Helps Agencies Prepare for the Worst. Home Healthcare Now, 25(7), 487-487.

Michael, M., Helm, E., & Graafeiland, B. (2009). Influenza Vaccination with a Live Attenuated Vaccine. American Journal of Nursing, 109(10), 44-48.

Molyneux, J. (2009). The Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Virus Vaccine. American Journal of Nursing, 109(9), 19.

Molyneux, J. (2010). The Top Health Care News Story of 2009: The Economy on Life Support, Health Care in Transition. American Journal of Nursing, 110(1), 16.

Nap, R., Andriessen, M., Meessen, N., Miranda, D., & Van der Werf, T. (2008). Pandemic Influenza and Excess Intensive-Care Workload. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 14(10), 1518-1525.

New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. (2007). Avian and Pandemic Influenza Preparedness for Primary Care Providers. Web.

Palazzo, M. (2001). Teaching in crisis. Patient and family education in critical care. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am, 13(1), 83-92.

Parry, H., Damery, S., Fergusson, A., Draper, H., Bion, J., & Low, A. (2011). Pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 in a critical care and theatre setting: beliefs and attitudes towards staff vaccination. J Hosp Infect, 78(4), 302-7.

Payne, K., & Rushton, C. (2007). Ethics in Critical Care: Ethical Issues Related to Pandemic Flu Planning and Response. AACN Advanced Critical Care, 18(4), 356 – 360.

Skelton, A. (2006). Commentary: Private Sector Planning, Preparedness, and Response Activities to Reduce the Impact of Pandemic Influenza. Journal of Public Health Management & Practice, 12(4), 381 – 387.

Sprung, C., Zimmerman, J., Christian, M., Joynt, G., Hick, J., Taylor, B., … Adini, B. (2010). Recommendations for intensive care unit and hospital preparations for an influenza epidemic or mass disaster: summary report of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine’s Task Force for intensive care unit triage during an influenza epidemic or mass disaster. Intensive Care Med, 36(1), 428–443.

Stephens, P. (2013). Our National Obsession with Flu Vaccine. American Journal of Nursing, 113(9), 11.

Tegtmeyer K., Conway, E., Upperman, J., & Kissoon, N. (2011). Education in a pediatric emergency mass critical care setting. Pediatr Crit Care Med, 12(6), 135-40.

Veenema, T., & Toke. (2007). When Standards of Care Change in Mass‐Casualty Events. American Journal of Nursing, 107(9), 72-73.

Victoria, D. (2007). Questions and Answers on Pandemic Influenza. American Journal of Nursing, 107(7), 50-56.

Webb, S. A., Pettilä, V., Seppelt, I., Bellomo, R., Bailey, M., Cooper, D.,…Yung, M. (2009). Critical care services and 2009 H1N1 influenza in Australia and New Zealand. N Engl J Med, 361(20), 1925-34.