Background

The postoperative complications of abdominal surgeries present a critical risk to patients’ health. The most invasive operations, such as cystectomy, colorectal and gynecological procedures, and gastrointestinal surgeries, are associated with high mortality and morbidity rates. In particular, Tevis and Kennedy (2016) found that after colorectal surgeries, mortality could reach 16.4 percent, and morbidity – 35 percent. Of seven million operations performed worldwide annually, at least 50 percent carried associated problems regarded as preventable, as reported by Debas et al. (2015). The complications associated with abdominal surgery include infections, venous thromboembolism events (VTEs), gastrointestinal paralysis, pulmonary issues, as well as nausea and vomiting.

The influence of perioperative care on the results of surgical treatment of patients has recently received particular attention. It is largely considered by the related evidence that not only the surgical practices but also postoperative interventions affect patient recovery (Ljungqvist, Scott, & Fearon, 2017; Tevis, & Kennedy, 2016). The application of the traditional care approach seems to be outdated and conservative. It leads to the increased length of hospital stay (LOS), readmissions, and greater health care costs – more than $16000 per patient in the United States (U.S.), which is the highest expenditure compared to other developed countries (Hurley et al., 2016; Tan, Lamb, & Kelly, 2015). Considering that the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) set the course on reducing costs while boosting care quality, the described problem cannot be overestimated (Kronick, 2016). The overutilization of healthcare resources and the failure of the current system to standardize care procedures are the two main factors that lead to additional spending.

In the context of modern technology development and innovation implementation, the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol was offered by Professor Kehlet in the 1990s (Tan et al., 2015). This concept is based on a multimodal approach and includes limiting the volume of infusion therapy, carrying out adequate anesthesia with minimizing the administration of opioid analgesics, and restoring patient mobility. The preoperative preparation of patients, careful monitoring during surgery, and postoperative management are proposed as the key points of ERAS. Such principles allow facilitating the rehabilitation of patients after surgery and reduce the level of adverse effects.

The current literature presents significant evidence that documents the effectiveness of ERAS in colorectal therapy, while other areas, such as urology, gynecology, and gastroenterology, need to be explored in detail. Among the pivotal benefits that directly impact patient recovery, Mosquera, Koutlas, and Fitzgerald (2016) enumerate faster bowel function restoration, shorter length of stay at the hospital after surgery, and decreased morbidity. Compared to the conventional method of patient recovery, ERAS provides a more comprehensive and useful approach to interprofessional team practice (Koo, Brace, Shahzad, & Lynn, 2013). It should also be noted that feasibility and cost-effectiveness studies point to the great potential of ERAS to be adopted with regard to patients undergoing different abdomen surgeries (Mosquera et al., 2016). The retrospective analysis of the literature shows that many efforts were applied to implement ERAS in clinical settings, yet much is to be done to make it more beneficial.

The rationale for Conducting the Systematic Review (What is to Be Learned and How Will the Review Add to Literature) and Importance to Nursing

Today, ERAS is successfully implemented in a number of leading hospitals (Mosquera et al., 2016). However, its introduction possesses several obstacles: excessive caution of doctors and unwillingness to retreat the conservative methods (Vukovic & Dinic, 2018). Only the focused teamwork of surgical physicians, anesthetists, rehabilitologists, clinical pharmacologists, medical personnel, and other necessary specialists can ensure that ERAS will be effective. It should also be mentioned that both care providers and patients are not sufficiently informed about new treatment options (Pędziwiatr et al., 2015). The thorough analysis of the state of this method in the U.S. allowed Vukovic and Dinic (2018) to conclude that it is necessary to familiarize clinicians and patients more closely with the achievements of ERAS and conduct training. Given the importance of the problem, the development of national clinical guidelines seems to be relevant.

The ways ERAS is adopted in the U.S. and related barriers will be learned in this systematic review, thus adding to the bulk of the existing academic literature and benefiting nursing. More to the point, the role of advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) will be examined in such areas as education, staff management, and problem-solving (Ljungqvist, Scott, & Fearon, 2017). Since APRNs are the key persons who drive change and monitor its impact on patients and healthcare in general, their contribution seems to be significant. The outcomes of this scholarly work are likely to equip them with an instrument and insights on how to manage nurses and achieve the highest care quality possible. Most importantly, the effectiveness of ERAS for patients undergoing abdominal surgery will be assessed and analyzed. It is anticipated that the results of this systematic review will enrich the current theoretical perspectives and foster further research.

The objective of the Review

The purpose of this systematic review is to contribute to the comprehending of the role of ERAS in decreasing the complications of abdominal surgery in patients, advancing their recovery period, and minimizing health care costs. The population, intervention, comparison, and outcomes (PICO) question: in patients undergoing abdominal surgery, what is the impact of implementing ERAS on patient recovery? The systematic review will be organized with regard to such specialties as urology (GU); gynecology (GYN); colorectal procedures, and gastroenterology (GI). The following specific questions may be formulated:

- How does ERAS impact patient recovery after abdominal surgery?

- What is the role of ERAS in reducing healthcare costs?

- What is the potential contribution of APRNs in implementing ERAS?

Methodology

Information Sources and Search Strategy

The Florida International University (FIU) portal was used to search necessary information on CINAHL, MEDLINE, Joanna Briggs Institute Evidence-Based Practice (JBI EBP), and Cochrane databases. Only CINAHL and MEDLINE databases demonstrated pertinent articles for this report. “Enhanced recovery after surgery“, “ERAS”, “implement”, “patient recovery”, “abdominal surgery”, and “patient outcome” keywords, word variations, and boolean phrases of “AND” and “OR” were utilized. Medical subject headings (MeSh/MH) served to refine the search.

Study Selection, Screening Method, and Inclusion / Exclusion Criteria

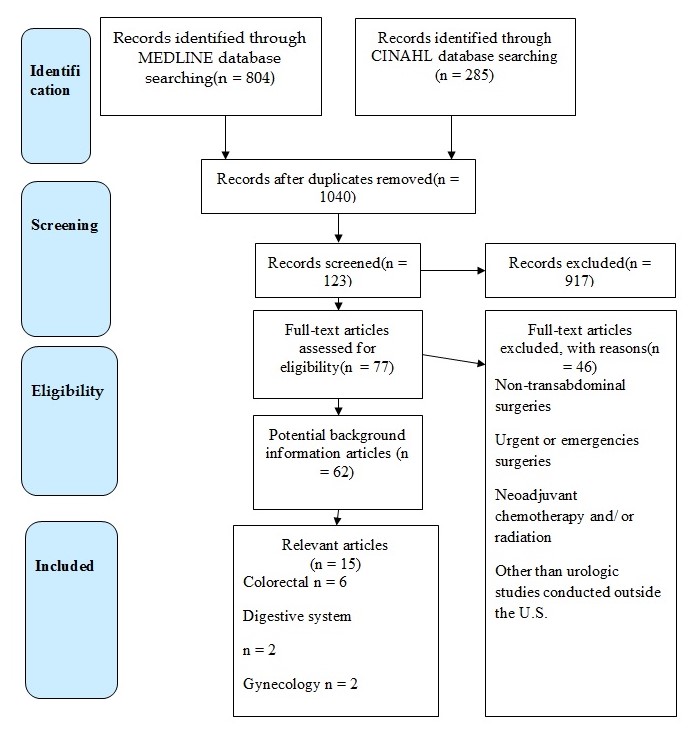

The study selection process was based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA), which is presented in Diagram 1. All the 1040 studies found in the mentioned databases, were screened on their relation to the PICO question and inclusion/ exclusion criteria. The review of 123 articles revealed 15 eligible studies on such topics as colorectal (6), gynecology (2), digestive system (2), and urology (5). Among the inclusion criteria that were utilized to choose the studies, one may enumerate the English language, the availability of a full text, publication date (from January 1, 2010, to March 31, 2019), and the geographical area of the U.S. Considering urology as the specialty of interest for the quality project, an exception was made to include relevant studies performed abroad. The failure of the article to focus on perioperative and postoperative care was regarded as the exclusion criteria. In addition, the sources that provided information on emergency and non-transabdominal surgeries were also rejected.

Data Collection and Items

The evaluation of research articles and clinical practice guidelines were used as the data collection method. In particular, title or abstract screening conducted previously was supplemented by the fill review of the content of the selected studies. To assess their quality, the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Research Evidence Appraisal tool was applied, and one of the evidence levels was given to each of 15 articles (Holly, Salmond, & Saimbert, 2016). Accordingly, data items included patient experience, healthcare costs, actions of APRNs, and several care units/topics that were specified in the previous paragraph.

Theory Utilized to Guide the Study

The innovation diffusion theory by Rogers was used to guide this systematic review. It aims to provide the introduction of one or another innovative idea into practice through a set of stages: knowledge, persuasion, decision, implementation, and confirmation (Birken et al., 2015). The utilization of this theory seems to be appropriate as it informs the study and clarifies how the conservative approach to care may be replaced by a more relevant one. In order to make innovation happen, it is essential to understand the current state of affairs, existing barriers, and the effectiveness of the proposed intervention, which are the key points of the innovation diffusion theory.

Results

Study Selection

The search for reliable and informative articles revealed 804 studies in the MEDLINE database and 285 articles in the CINAHL database. The elimination of duplicates left 1040 articles, and 917 did not meet inclusion/exclusion criteria. Of 77 full-text articles, 62 were potential background studies, and 15 relevant studies composed the final sample for this systematic review. The colorectal bulk of research included 6 articles, urology – 5, gynecology – 2, and digestive system – 2.

Study Characteristics

The studies synthesized in this systematic review included a sufficient number of participants, who were examined based on the intervention and control groups. Most of the studies were prospective or retrospective when the historical patients with abdominal surgery were enrolled in one group, and those who received ERAS composed the other one. The comparative nature of the studies was appraised as beneficial to comprehending the impact of ERAS on patients undergoing various types of abdominal surgery. The combination of qualitative and quantitative research methods allowed revealing more trends and gaps in the current literature. All the articles included in the review are of high quality as they present evidence-based data and clearly explain the results.

Risk of Bias Within and Across Studies

Since this systematic review relies on data from the primary sources, their sources of bias should be identified. The first risk of bias refers to incomplete outcome data that was received by some of the included articles. Due to the focus on one or several aspects of the given health problem, it may be challenging to generalize their results to greater conclusions. In addition, a range of factors may also affect the outcomes within and across studies, which increases the risk of bias of inappropriate statements. For example, only two of the articles included a single surgeon, which minimizes any related bias, while others were conducted in the general surgical environment.

Results of Individual Studies and Intervention Effect on the Outcome of Interest

Urology

Sample

Each of the studies mentioned included relatively large samples (from 70 to 300+ participants), which were, however, conventionally recruited within one hospital, institution, or database. Moreover, some studies such as the one by Persson et al. (2015) underrepresented women among its participants. Age-wise, study samples were homogenous and included mature and elderly adults with a small percentage of them being over the age of 75.

Setting

All of the mentioned studies were conducted in a clinical setting, namely, in urological and post-operative departments of the respective medical facilities. The study findings relied on objective data gathered through patient examination and progress tracking such as the time to the first defecation. If a study implied investigating post-discharge deliverables, it included clear discharge criteria..

Research Design

All of the studies, except for one, employed prospective research design and were based on the observation of phenomena or the lack thereof in progress. The only study that used a retrospective design was the one by Palumbo et al. (2018). The authors noted that their choice was justified by the fact that they compared and contrasted two virtually contemporary cohorts of patients, therefore, rendering their methods relevant.

Interventions

The authors ensured fewer or no bowel preparation procedures prior to the medical invasion. Such studies as the ones by Persson et al. (2015) and Lin et al. focused on early food and water intake to stimulate bowel activity. The majority of the studies advocated for early ambulance and mobility, which might have also contributed to the reduced LOS in ERAS patients.

Key Findings

Speaking of the complications after surgery, one should state that bowel function recovery and fewer readmissions were the key indicators of ERAS’ advantageous impact. The secondary goal of determining the financial effect of the given intervention was also completed: it is found that in one of the studies it was decreased, and the patients of the other study detected in significant growth in costs, but the variance in billed charges was reduced. The studies under investigation did not show conclusive results regarding LOS after ERAS implementation.

Clinical Outcomes

As the analysis has shown, ERAS implementation tended to lead to improved clinical outcomes. LOS remained the same or was slightly shorter as compared to traditional post-operative treatment. Two studies demonstrated faster bowel function recovery after surgery (Lin et al., 2018; Chipollini et al., 2017). Two out of five studies implied lower complication rates for ERAS patients (Persson et al., 2015; Palumbo et al., 2018).

LOS

The findings of the articles presented in the above table vary, showing different results: two of five studies report that LOS did not change essentially (Lin et al., 2018; Persson et al., 2015), while others emphasize that the intervention groups reduced their stay at the hospital for approximately three days. Thus, one may say that the current evidence is not exactly conclusive, and the issue needs further investigation.

Gynecology

Sample

Both studies had relatively large samples – a total of 267 participants recruited for the one by Bergstrom et al. (2018) and 376 for the one by Boitano et al. (2018). While the study by Boitano et al. (2018) examined ERAS and non-ERAS patients with the ratio of 1:1, in the study by Bergstrom et al. (2018), non-ERAS participants were somewhat overrepresented (60%). The authors did not mention the gender ratio of their samples; however, the first study provided the mean age (51.7 and 55.2 for control and intervention groups respectively).

Setting

Both Bergstrom et al. (2018) and Boitano et al. (2018) conducted their studies in a clinical setting within one institution, namely, gynecological and post-operative departments of the chosen medical facilities. Given the retrospective design of both studies, historical patients that constituted the control group were investigated using accessible data from medical records. The study findings relied on objective data rather than subjective reports from patients.

Research Design

Both studies employed retrospective control trial design without randomization, which is a major flaw as it does not allow to render the findings precisely inferential. Bergstrom et al. (2018) noted that the study methodology suffered from the lack of consensus on appropriate ERAS practices and interventions. In particular, ERAS guidelines had yet to be comprehensively translated into surgical practices, especially in regards to gynecology.

Interventions

The study by Bergstrom et al. (2018) included all phases of ERAS intervention: preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative measures. The research piece by Boitano et al. (2018), on the other hand, only focused on ERAS implementation post-operation. Bergstrom et al. (2018) mentioned that they had to additionally comply with the US guidelines for treating gynecological cancer patients. Therefore, they were obliged to monitor their participants for perioperative thromboembolism.

Key Findings

The studies revealed positive and neutral outcomes in patients who underwent ERAS interventions. The average LOS did not vary significantly among patients in the intervention and control groups. However, ERAS participants in the study by Boitano et al. (2018) reported milder ileus – nausea, and vomiting after surgery. Bergstrom et al. (2018) note that ERAS patients needed less narcotic analgesia due to the chosen treatment method.

Clinical Outcomes

No difference was noted between the control and intervention groups regarding LOS, 30-day readmissions, and complications associated with the postoperative period, which is also reflected by de Groot et al. (2018). Nevertheless, the positive point refers to the reduced use of narcotics to relieve patients’ pain, and venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis was received by many patients as a preventative measure. It should be stressed that not all patients received quality and safe VTE education, which identified the necessity to introduce audit measures for continuous control and monitoring. Since patients with PD tend to have thoracic epidural analgesia (TEA), this should be taken into account while implementing ERAS protocols. In general, the gynecologic literature seems to be quite limited to discussing ERAS, while the compliance of the available studies is not often considered (Lambaudie et al., 2017). Morbidity and mortality rates remained similar to control groups compared to intervention cohorts.

LOS

The key benchmark of quality improvement in laparotomy surgery is LOS, which was not met by some of the studies. The study by Bergstrom et al. (2018) demonstrated no significant differences in LOS after ERAS was implemented. On the other hand, the research conducted by Boitano et al. (2018) revealed a significant decrease in LOS from 4.0 to 2.9 days. For the lack of studies on the subject, this evidence cannot be considered conclusive, and the association between ERAS use and LOS needs further research.

Colorectal

Sample

The number of patients recruited for the studies, varied greatly – from 78 to 1036. Admittedly, larger samples may account for greater research validity and render the findings inferential. The majority of the studies ensured a 1:1 ratio for cohorts enrolled in control and intervention groups, safe for the one by Zoog et al. (2018) where the sample was dominated by so-called historical patients.

Setting

The overwhelming majority of the studies examined patients in clinical settings. The only exception is the study by Martin et al. (2016) the front and center of which was SJMH administrative and clinical databases research, which did not imply any actual patient contact and examination. This type of setting did not allow the researchers to have much control over interventions.

Research Design

The majority of the studies mentioned employed retrospective comparative design that relied heavily on database research and post-factum observations. The only prospective study among those described is that by Geltzeiler et al. (2014) that included intervention, observation, and data analysis over the course of three years (2009, 2011, and 2012). While the studies varied in expected primary and secondary outcomes, the key criteria that the authors found significant were LOS, readmission rates, complication rates, and the prevalence of such morbid symptoms as ileus.

Interventions

First and foremost, ERAS implementation aimed at faster recovery and better care transition by means of conservative fluid management, early follow-ups, and early ambulance. Some of the studies such as the one by Zoog et al. (2018) set health promotion as one of its key objectives: the authors made sure that their patients understood the nature of procedures and the importance of self-management.

Key Findings

In some cases, ERAS proved to be economically efficient while traditional care costs were found to be more of a burden ($21,674 vs. $30,380) (Mosquera et al., 2016). In all six cases, the authors succeeded in reducing the average LOS – sometimes by as much as 50% (Geltzeiler et al., 2014). There is somewhat conflicting evidence concerning the effectiveness of ERAS in reducing readmission rates. For instance, a study by Martin et al. (2016) revealed that ERAS implementation contributed to higher readmission rates as opposed to those following traditional care application (14.6% vs. 8.7%).

Clinical Outcomes

The results reported by Fabrizio et al. (2017) demonstrate that the enhanced recovery pathways (ERPs) did not significantly reduce hospitalization rates. The positive impact of the intervention was associated with shorter hospitalization periods; however, the improved recovery was marked as noticeable with regard to site infections, while the cases of small bowel obstruction increased in number. Accordingly, it is possible to assume that the reproducibility of ERAS is sufficient to implement it in other local hospitals. However, one should state that for the minimally-invasive surgery, ERP pathways proved to be highly effective, yet colon cancer presents more risks to patient outcomes due to preoperative chemoradiation (Martin et al., 2016). Therefore, patients with rectal cancer should be assigned ERA with greater attention, and discharge criteria should be adjusted for them.

Another important area that was covered by many studies is patient and family satisfaction changes. The comparison of two cohort groups by Fabrizio et al. (2017) revealed no difference in the attitudes of those who received ERAS protocol and did not, yet patients exposed to readmission rated their experience lower than those who avoided repeated hospitalizations. More positive results are shown in the study by Miller et al. (2014), who found that patients from the traditional group experienced higher pain rates compared to the intervention group, which is characteristic of their comfort levels. The colorectal surgery and the subsequent ERAS implementations were associated with fewer days of staying at the hospital. In order to facilitate the recovery process, patients were often encouraged to stay on the day of operation and spent at least six hours out of bed during further days.

LOS

Along with hospitalization rates, LOS is one more significant factor that points to the success of the recovery-related intervention. The research by Mosquera et al. (2016) demonstrated an almost 30% difference after ERAS implementation (6.4 days vs. 9.2 days) whereas Geltzeiler et al. (2014) came to even more promising conclusions. In their case, following ERAS guidelines helped to reduce LOS almost in half – from 6.7 to 3.7 days.

Gastroenterology

Sample

Both studies succeeded in recruiting a significant number of participants – 180 and 397. Morgan et al. (2016) maintained a 1:1 men-to-women ratio to make sure that both genders are represented. Nevertheless, the traditional care patients (control group) accounted for 78% of the sample while ERAS patients – only 22%. This ratio may be explained by the retrospective design and the higher accessibility to past medical records.

Setting

In both cases, research took part in a clinical setting – in Carolinas Medical Center (Aviles et al., 2017) and South Carolina Medical University (Morgan et al., 2016). However, due to the retrospective study design, Morgan et al. (2016) also worked with RedCAP electronic databases. The access was provided as a part of the grant issued by the South Carolina Center for Translational Research.

Research Design

Both studies compared and contrasted two groups of patients – traditional care and ERAS – against each other in a controlled trial. However, the study by Aviles et al. (2017) employed a prospective design as its authors observed the phenomena in progress and could intervene at any point. The retrospective design of the study by Morgan et al. (2016) may be one of its downsides since researching databases gives one much less control over the process and consequently, the outcomes.

Interventions

Morgan et al. (2016) and Aviles et al. (2017) made sure to follow ERAS guidelines in their research. However, in the first case, every phase was a priority – preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative, while in the second case, perioperative care was the focus of researchers. Morgan et al. (2016) singled out two essential elements of care, which they used in their study: the restriction of IV fluid administration and preoperative carbohydrate loading to prevent insulin resistance during surgery.

Key Findings

The study by Aviles et al. (2017) proved that enhanced recovery for pancreatic cancer patients was possible through comprehensive ERAS implementation. However, as compared to standard care, ERAS did not show any advantages regarding LOS, readmission rates, and morbidity rates. The study by Morgan et al. (2016) demonstrated vastly different results. ERAS was found more efficient than standard care based on each and every criterion.

Clinical Outcomes

Evidence regarding the effectiveness of ERAS in patients undergoing gastric surgery is not consistent even though some similar outcomes can be noted, which is also supported by Yamada et al. (2014). In particular, the key goal of reducing hospital days was achieved in the course of safe implementation of ERAS guidelines in clinical settings. Since this data was not proved by one of the reviewed articles, further research should explore this issue in detail via experimental studies and mixed methods design.

Length of Stay

For Morgan et al. (2016), measuring LOS post-implementation was one of the secondary research objectives. Consequently, the authors did not find any significant differences in LOS between control and intervention groups. Aviles et al. (2017) came to somewhat different conclusions: their study showed that following ERAS guidelines accounted for a decrease in LOS from 9.2 to 7.4 days.

Real and Perceived Barriers to ERAS Implementation

According to Paton et al. (2014), one of the main obstacles on the way to ERAS implementation is the lack of practice standardization, which explains significant variations in current post-operative care. Today’s procedures often lag behind the most recent evidence, and health workers find it difficult to translate scientific findings into practice. Many features of ERAS protocols require an interdisciplinary team of motivated professionals with an internally driven accountability and ownership mindset. Since nurse depression, anxiety, and compassion fatigue are real, observable phenomena, one may assume that mental disorders and stress may prevent affected professionals from leading the change (Hegney et al., 2014). Lastly, rigid organizational structures may be a real barrier to ERAS implementation. ERAS protocols are not only relevant – they constantly change and expand, and many facilities are not ready to readjust.

Facilitating Implementation of ERAS

A nurse can facilitate ERAS implementation and promote change at his or her medical facility. First and foremost, nurses should commit to lifelong learning and continuing education, which implies consulting reliable sources of information and being able to discern a bogus study from a valid one. By educating themselves, health practitioners may start questioning established practices at their facility and ponder new ways to improve patient outcomes. Another important change to be made is developing a teamwork mindset and a sense of responsibility for one’s actions. A team may use each member’s skills and expertise efficiently and allocate limited sources for the common good.

Generalizability of Conclusions

The existing evidence concerning the applicability and reliability of ERAS protocols seems quite promising. However, there is some conflicting data that does not allow for putting together a full picture. For instance, described studies show different outcomes regarding LOS with some revealing a reduction as significant 50% and the others concluding no statistical differences as compared to traditional care. Further, according to some studies, readmission rates did not improve after ERAS implementation. So far, it is possible to presume that ERAS seems to be an appropriate strategy to relieve postoperative symptoms such as ileus.

Gaps in Research and Limitations

The studies analyzed have demonstrated some significant limitations such as insufficient sample size and underrepresentation of certain demographic cohorts. Almost in all the studies, the participants belonged to the same age group (>50) and were racially and ethnically homogenous. Moreover, convenience sampling employed in every research piece under investigation did not account for statistical conclusions that could be truly inferential. Further, traditional care to which control groups were subject was not exactly specified. There is a likelihood that preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative care varied across the medical facilities involved.

Conclusions and Recommendations for Future Research

In summation, ERAS protocols seem to be a feasible alternative to standard pre-, intra-, and postoperative care. There is evidence that ERAS practices help mitigate postoperative symptoms, require less narcotic analgesia, and allow for faster recovery and ambulance. Future research should focus on expanding and diversifying study samples to include different demographic cohorts. It is also essential to clarify what ERAS guidelines should and should not include and how exactly they need to be adjusted depending on the field of application. This is especially relevant for fields such as gynecology and gastroenterology since there is very little evidence concerning ERAS implementation. Lastly, there is a need to make patient education part of ERAS implementation on site and study readmission rates given ongoing support and counseling.

Discussion

Summary of the Evidence

The included studies were scholarly articles retrieved from relevant medical databases and providing important knowledge regarding ERAS and patient recovery after abdomen surgery. The quality of the considered studies was regarded as sufficient to meet the inclusion criteria and offer valuable data to enrich the understanding of the topic. Some studies were excluded due to the unavailability of their full texts, background information, a focus on non-transabdominal surgeries, and non-U.S. context. Since the number of such operations tends to grow, this area presents an especial interest to surgeons and APRNs as those who are expected to lead change (Yamada et al., 2014). The improved care quality was identified as the key indicator of success in gastrointestinal, urologic, gynecologic, and colorectal therapy practices. The findings of this systematic review are consistent with Patel and Semerjian (2017), who emphasize the potential of ERAS protocols in reducing complications and LOS in the field of urology. Similar outcomes were noted for other mentioned areas, which provide the opportunity for care professionals to work more on improving patient outcomes.

The reduction of complications in the post-surgery and follow-up periods is specified by the literature as one of the most important benefits. The number of ileuses and the use of narcotic analgesia decreased significantly, which is especially evident in the articles that focused on colorectal and urologic surgeries. The studies exploring ERAS in the context of gynecology revealed little difference between control and intervention groups with regard to complications and readmissions, which can probably be explained by the insufficient experience of implementing ERAS pathways in this area of interest (Bergstrom et al., 2018). The reduction in patient care variation is another significant aspect that was expected to be explored in the course of the systemic review. Based on the results obtained by the included studies, one may claim that ERAS is advantageous in care variation decrease as it proposes clear and standardized practices, which can change depending on the area, yet overall guidelines are analogous. In particular, early nutrition, staying out of bed, vacuum methods of post-surgery recovery, patient education, and follow-up within 30 or 90 days compose the key prospects of ERAS.

The optimized perioperative patient management integrates the possibility of a combination of elements of ERAS philosophy and the options available in each specific clinic. It is considered that informing patients about all stages of treatment and discussing the perioperative period and features of the postoperative period are the central elements of ERAS effectiveness. Consistent with other available articles, this systematic review results suggest that full and timely pain relief, which is achieved by setting an epidural catheter for prolonged intra- and postoperative analgesia, is of paramount importance (Koo et al., 2013).

In the view of the analyzed studies, the expansion of the role of APRNs can be regarded as a feasible and reliable way to improve staff awareness of ERAS. One should also state that Bergstrom et al. (2018) discusses the main barrier to the successful adoption of ERAS, such as the compliance of staff to new care principles. Similar ideas are expressed by other articles that attempt to determine the challenges related to this method utilization (Birken et al., 2015; Hurley et al., 2016). In this connection, it seems significant to identify the potential contribution of APRNs as the primary promoters of change. Koo et al. (2013) emphasize that their focus on practice regulation, education, and workforce distribution are essential for organizing, implementing, and monitoring ERAS protocols.

By leveraging the role of APRNs, it is possible to achieve greater compliance with new pathways and ensure that the current indicators of LOS, readmissions, and complications would be lowered. At the same time, collaboration among the members of the interdisciplinary team is specified as the paramount premise of effective ERAS provision before, during, and after surgery. The analysis of ERAS costs was another secondary goal of this systematic review, and it was found that it is not associated with significantly higher charges for patients or hospital spending. Even though some studies reported an increase in costs, the overall variation of patient charges remained or was reduced. The alternative explanation of the results, namely, their heterogeneity in some cases, was presumably caused by their varying directions, clinical settings, and methods used to collect and interpret data.

This systematic review reveals some literature gaps that should be examined in future research. First of all, it is critical to conduct studies that would adopt a comprehensive approach to studying ERAS as a recovery intervention for patients having abdomen surgery. In particular, the current articles tend to focus on one or two aspects such as LOS, while there is a need to pay attention to more issues within one study, including patient perceptions, comfort, site infection, et cetera. The follow-up is one more area that is underrepresented in the current body of the academic literature.

Limitations

The limited sample size of 15 articles restrict the generalizability of results. Since no information from national databases or large reports was included, it is not possible to generalize data to larger extents. Nevertheless, the outcomes identified provide valuable insights into the experience of adopting ERAS in clinical settings. One of the key limitations that can be listed with regard to the studies reviewed in this paper is the emphasis of many studies on a single care success factor. Also, the relatively small sample may be regarded as an issue that limits the generalization of results.

Conclusions

To conclude, this systematic literature review attempted to integrate the literature on the impact of ERAS on patients undergoing one of the following abdomen surgeries: colorectal, gastrointestinal, urological, and gynecological. The majority of the studies are focused on either colorectal or urological health issues since these areas were initially offered as the ones that are appropriate to utilize ERAS. The two other spheres also tend to be focused on ERAS pathways as the opportunity to enhance care quality and reduce patient care variation. It was revealed that the given multimodal perioperative care treatment program allows reducing LOS, readmissions, and complications without adverse changes in morbidity, mortality, and patient charges. The systematic review also identified that the efforts of APRNs and cooperation between interprofessional care providers are critical to effectively implementing ERAS protocols.

Further research is necessary to examine broader opportunities for using ERAS in clinical settings from different perspectives. It is needed to comprehend how to improve its positive impact and accomplish better patient outcomes. The potential benefits of ERAS should be explored in a comprehensive manner to reveal any links between them and also adjust some practices if required. In addition, the barriers to the adoption of ERAS should be analyzed in order to design the strategies to address them, thus making the perioperative practices more relevant to the needs of patients. The perceptions of patients as well as the compliance of their education to ERAS protocols should be evaluated as well since little attention is paid to their views and factors that enhance faster recovery, such as family support.

References

Aviles, C., Hockenberry, M., Dionisios Vrochides, M. D., Iannitti, D., Cochran, A., Tezber, K. … Desamero, J. (2017). Perioperative care implementation: Evidence-based practice for patients with pancreaticoduodenectomy using the enhanced recovery after surgery guidelines. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 21(4), 466-472.

Bergstrom, J. E., Scott, M. E., Alimi, Y., Yen, T. T., Hobson, D., Machado, K. K.,… Levinson, K. (2018). Narcotics reduction, quality and safety in gynecologic oncology surgery in the first year of enhanced recovery after surgery protocol implementation. Gynecologic Oncology, 149(3), 554-559.

Birken, S. A., DiMartino, L. D., Kirk, M. A., Lee, S. Y. D., McClelland, M., & Albert, N. M. (2015). Elaborating on theory with middle managers’ experience implementing healthcare innovations in practice. Implementation Science, 11(1), 2-7.

Boitano, T. K., Smith, H. J., Rushton, T., Johnston, M. C., Lawson, P., Leath III, C. A.,… Straughn Jr, J. M. (2018). Impact of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol on gastrointestinal function in gynecologic oncology patients undergoing laparotomy. Gynecologic Oncology, 151(2), 282-286.

Chipollini, J., Tang, D. H., Hussein, K., Patel, S. Y., Garcia-Getting, R. E., Pow-Sang, J. M.,… Poch, M. A. (2017). Does implementing an enhanced recovery after surgery protocol increase hospital charges? Comparisons from a radical cystectomy program at a specialty cancer center. Urology, 105, 108-112.

de Groot, J. J., Maessen, J. M., Dejong, C. H., Winkens, B., Kruitwagen, R. F., Slangen, B. F.,… all the members of the study group. (2018). Interdepartmental spread of innovations: A multicentre study of the enhanced recovery after surgery programme. World Journal of Surgery, 42(8), 2348-2355.

Debas, H. T., Donkor, P., Gawande, A., Jamison, D. T., Kruk, M. E., & Mock, C. N. (2015). Essential surgery: Disease control priorities (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Fabrizio, A. C., Grant, M. C., Siddiqui, Z., Alimi, Y., Gearhart, S. L., Wu, C.,… Wick, E. C. (2017). Is enhanced recovery enough for reducing 30-d readmissions after surgery? Journal of Surgical Research, 217, 45-53.

Geltzeiler, C. B., Rotramel, A., Wilson, C., Deng, L., Whiteford, M. H., & Frankhouse, J. (2014). Prospective study of colorectal enhanced recovery after surgery in a community hospital. JAMA Surgery, 149(9), 955-961.

Hegney, D. G., Craigie, M., Hemsworth, D., Osseiran‐Moisson, R., Aoun, S., Francis, K., & Drury, V. (2014). Compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, anxiety, depression and stress in registered nurses in Australia: Study 1 results. Journal of Nursing Management, 22(4), 506-518.

Holly, C., Salmond, S., & Saimbert, M. (2016). Comprehensive systematic review for advanced practice nursing (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Hurley, M. P., Schoemaker, L., Morton, J. M., Wren, S. M., Vogt, W. B., Watanabe, S., … & Bhattacharya, J. (2016). Geographical variation in surgical outcomes and costs between the United States and Japan. American Journal of Managed Care, 22(9), 600-607.

Koo, V., Brace, H., Shahzad, A., & Lynn, N. (2013). The challenges of implementing enhanced recovery programme in urology. International Journal of Urological Nursing, 7(2), 106-110.

Kronick, R. (2016). AHRQ’s role in improving quality, safety, and health system performance. Public Health Reports, 131(2), 229-232.

Lambaudie, E., De Nonneville, A., Brun, C., Laplane, C., Duong, L. N. G., Boher, J. M.,… Houvenaeghel, G. (2017). Enhanced recovery after surgery program in gynaecologic oncological surgery in a minimally invasive techniques expert center. BMC Surgery, 17(1), 136-145.

Lin, T., Li, K., Liu, H., Xue, X., Xu, N., Wei, Y.,… Tong, S. (2018). Enhanced recovery after surgery for radical cystectomy with ileal urinary diversion: A multi-institutional, randomized, controlled trial from the Chinese bladder cancer consortium. World Journal of Urology, 36(1), 41-50.

Ljungqvist, O., Scott, M., & Fearon, K. C. (2017). Enhanced recovery after surgery: A review. JAMA Surgery, 152(3), 292-298.

Martin, T. D., Lorenz, T., Ferraro, J., Chagin, K., Lampman, R. M., Emery, K. L.,… Vandewarker, J. F. (2016). Newly implemented enhanced recovery pathway positively impacts hospital length of stay. Surgical Endoscopy, 30(9), 4019-4028.

Miller, T. E., Thacker, J. K., White, W. D., Mantyh, C., Migaly, J., Jin, J.,… Moon, R. E. (2014). Reduced length of hospital stay in colorectal surgery after implementation of an enhanced recovery protocol. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 118(5), 1052-1061.

Morgan, K. A., Lancaster, W. P., Walters, M. L., Owczarski, S. M., Clark, C. A., McSwain, J. R., & Adams, D. B. (2016). Enhanced recovery after surgery protocols are valuable in pancreas surgery patients. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 222(4), 658-664.

Mosquera, C., Koutlas, N. J., & Fitzgerald, T. L. (2016). A single surgeon’s experience with enhanced recovery after surgery: An army of one. The American Surgeon, 82(7), 594-601.

Palumbo, V., Giannarini, G., Crestani, A., Rossanese, M., Calandriello, M., & Ficarra, V. (2018). Enhanced recovery after surgery pathway in patients undergoing open radical cystectomy is safe and accelerates bowel function recovery. Urology, 115, 125-132.

Patel, H. D., & Semerjian, A. (2017). Enhanced recovery after surgery protocols to reduce morbidity in the aging patient. European Urology Focus, 3(4-5), 313-315.

Paton, F., Chambers, D., Wilson, P., Eastwood, A., Craig, D., Fox, D.,… & McGinnes, E. (2014). Effectiveness and implementation of enhanced recovery after surgery programmes: A rapid evidence synthesis. BMJ Open, 4(7), e005015.

Pędziwiatr, M., Pisarska, M., Wierdak, M., Major, P., Rubinkiewicz, M., Kisielewski, M.,… Budzyński, A. (2015). The use of the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer – A comparative analysis of patients aged above 80 and below 55. Polish Journal of Surgery, 87(11), 565-572.

Persson, B., Carringer, M., Andrén, O., Andersson, S. O., Carlsson, J., & Ljungqvist, O. (2015). Initial experiences with the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS®) protocol in open radical cystectomy. Scandinavian Journal of Urology, 49(4), 302-307.

Semerjian, A., Milbar, N., Kates, M., Gorin, M. A., Patel, H. D., Chalfin, H. J.,… Robertson, L. (2018). Hospital charges and length of stay following radical cystectomy in the enhanced recovery after surgery era. Urology, 111, 86-91.

Tan W. S., Lamb, B. W., & Kelly, J. D. (2015). Complications of radical cystectomy and orthotopic reconstruction. Advances in Urology, 2015, 1-7.

Tevis, S. E. & Kennedy, G. D. (2016). Postoperative complications: Looking forward to a safer future. Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery, 29(3), 246-252.

Vukovic, N., & Dinic, L. (2018). Enhanced recovery after surgery protocols in major urologic surgery. Frontiers in Medicine, 5, 93-103.

Yamada, T., Hayashi, T., Aoyama, T., Shirai, J., Fujikawa, H., Cho, H.,… Fukushima, R. (2014). Feasibility of enhanced recovery after surgery in gastric surgery: A retrospective study. BMC Surgery, 14(1), 41-47.

Zoog, E., Simon, R., Stanley, J. D., Moore, R., Lorenzo-Rivero, S., Shepherd, B.,… Nelson, E. (2018). “Enhanced recovery” protocol compliance influences length of stay: Resolving barriers to implementation. The American Surgeon, 84(6), 801-807.