Problem Description

Long-term care (LTC) in the United States (U.S.) is one of the growing areas of healthcare that requires the focused attention of policymakers, care providers, and patients. LTC facilities provide quality care and offer necessary medical and psychological assistance to those with chronic diseases and the inability to care for themselves independently. The delivery of such care is costly, especially when patients need to be transferred to the hospital for acute healthcare events, which could have been handled in LTC.

In the U.S., LTC facilities such as nursing homes are regulated and monitored by a combination of both state and federal authorities. The state regulating body is the Department of Health (D.O.H.) and the federal regulating body is the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (C.M.S.). According to the U.S. Government Publishing Office, nursing homes should contact a patient’s provider once a month at a minimum, and providers are required to report any changes in a patient’s healthcare status (“Code of Federal Regulations: Section 483.70,” 2018). Federal guidelines state that patients in LTC facilities must be seen by a provider (physician, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant) within 30 days from the date of admission and then every 30 days for the first 90 days (Code of Federal Regulations: Section 483.70,” 2018). Furthermore, the guidelines mandate that after 90 days, the patient must be seen at a minimum of every 30-60 days with 10 days of slippage from the due date. At this time, the plan of care must also be reviewed with nursing staff and signed by the provider at a minimum every 2 months (The 2018 Florida Statutes, 2018). This infrequent communication between staff caring daily for those in LTC and infrequent provider visits causes delays in timely and proper recognition of issues, adjustment of the treatment plan, and hospitalizations that can be avoided. Levinson (2013) emphasizes that nursing homes transferred one out of four Medicare patients to hospitals in 2011, which cost Medicare 14.3 billion dollars. The identified problem affects not only patients but also their families and healthcare spending increases. The evidence shows that patients receiving LTC services are more likely to develop concomitant diseases and die. Additional issues and problems in LTC have made things worse, increasing the number of hospitalizations. These problems include staffing concerns, low reimbursement levels, and a lack of insurance coverage.

Background

According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (C.D.C.) Vitals and Health Statics reports, across the U.S. there are approximately 15,600 Nursing Homes of whom have 1.7 million licensed beds and as of 2015, there are 1.3 million nursing home patients

(Harris-Kojetin et al., 2019). The advances in health promotion and disease treatment achieved in the 21st century have led to longer lifespans. The population of baby boomers is becoming older, while their children tend to live far from their parents. As reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013), 20 percent of the population will be composed of older adults age 65 and over by 2030, and there will be 72 million older adults in the U.S. by 2038. In this growing older population, another problem associated with LTC issues is the key mortality and morbidity causes among these patients – the growth in chronic and comorbid diseases. Cardiovascular issues, diabetes, and mental disorders are common conditions in elderly patients who are hospitalized in general, while choking, falls, and suicidal intentions are the most common reasons for hospitalizations directly from LTC settings (Ibrahim et al., 2017). All these patient transfers to the emergency department and subsequent hospitalizations could be reduced by the use of skilled professionals working in LTC. In particular, advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) work is valued in such areas as by supporting the clinical staff (e.g., certified nursing assistant, licensed practical nurses, and registered nurses) close monitoring of patients with the timely assessment, development, and adjustment of care plans, and collaborative management provision (Donald et al., 2013).

Significance to Nursing

The contribution of APRNs is one of the effective interventions to address the identified problem. However, the last review of the scholarly literature on the given topic was conducted in 2010, which determines the need to update knowledge existing in this field (Donald et al., 2013). Therefore, a systematic review on the role of APRNs in reducing hospitalizations from LTC settings and impacting other aspects of the problem such as patient/family satisfaction, and lowering healthcare costs was conducted. The paramount goal of this review is to learn any progress and failures that are documented pertaining to APRNs in LTC by the selected articles from 2011 to 2019. In particular, it is critical to understand how APRNs impact patient outcomes with regard to patients in the LTC setting. From this review, an effective model using APRNs in LTC will be developed to improve patient outcomes. The review will add to the literature by extending and updating relevant information that can be used in future research. At the same time, nursing will also benefit as the new intervention will be studied, and practitioners, as well as care facilities, will receive the opportunity to adopt it in practice.

The objective of the Review

The purpose of this systematic review is to review studies from medical databases, select the pertinent ones using eligibility criteria, and assess their findings in the context of the role of APRNs in LTC. The key Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcomes (PICO) question is formulated as follows: are advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) effective in treating patients in long-term care (LTC) settings? Several sub-questions were developed to structure the systematic review and include

- Research question 1. What is the role of APRNs in reducing hospitalizations of patients in LTC?

- Research question 2. How does the integration of APRNs in LTC care affect patient and family satisfaction levels?

- Research question 3. What is the potential impact of APRNs in LTC with regard to decreasing financial burden?

- Research question 4. Are there any other improvements associated with the efforts of APRNs in LTC?

Methods

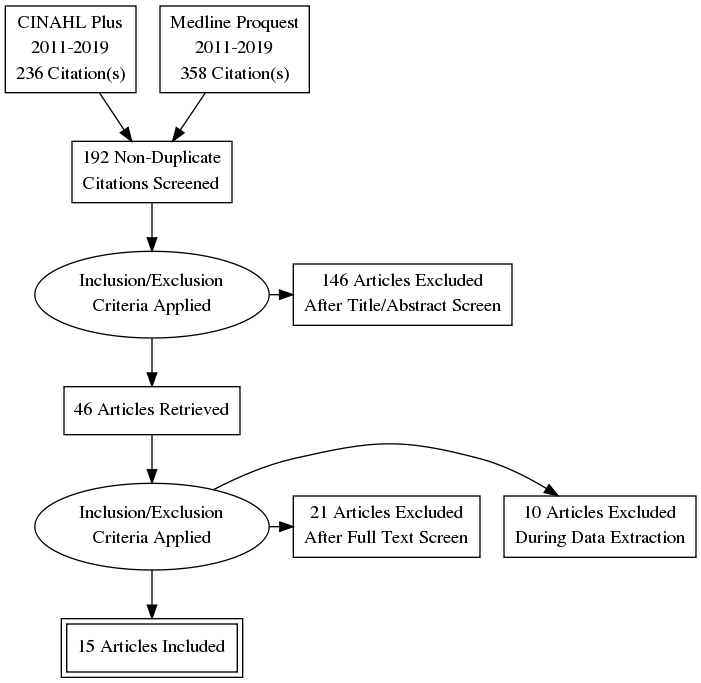

Databases such as CINAHL and Medline ProQuest were accessed via the Florida International University (FIU) online library portal to search for articles of interest. The following keywords were used: advanced practice registered nurse, nurse practitioner, APRN, nursing home, assisted living, residential care, long-term care, LTC, a lack of care, hospitalization, inappropriate care, poor care, and cost. These keywords were combined differently to collect a broad range of articles and select the most pertinent studies for the systematic review. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram was used as a screening strategy and study selection (Figure 1). Of 594 articles found in CINAHL Plus and MEDLINE ProQuest, 192 were chosen as a result of the elimination of duplicates. After the title and abstract screening, 146 articles were excluded and 15 met all inclusion and exclusion criteria. RefWorks ProQuest, an online program, was used to organize the findings and assist with keeping track of the study articles.

For this systematic review, three inclusion criteria were articulated in order to ensure the selection of the most appropriate studies. First, the English language was chosen as the only acceptable one: since all the articles were published in this language, all of them were included. Second, the publication date was considered, namely, the articles published from January 1, 2011, to March 6, 2019, were pinpointed as meeting this requirement. The publication in CINAHL Plus or MEDLINE ProQuest was the third criteria to be included in the review. The exclusion point was the failure to correspond to the main topic and the PICO question as a result of the title and abstract examination.

In order to appraise the articles and evaluate their quality, the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Research Evidence Appraisal Tool was utilized. Five evidence levels were regarded while determining the data quality, and each of the articles was assigned one of the following marks: high quality, good quality, or major flaws / low quality (Holly, Salmond, & Saimbert, 2011). The template offered by Johns Hopkins University was used to appraise the selected studies. Moran, Burson, and Conrad (2016) state that “the method used to organize the literature should be logical for the reader and allow for an easy retrieval” (p. 120). In this connection, data abstraction was performed by the researcher with respect to the identified problem and questions to be answered. The qualitative (narrative) analysis of the studies was employed as the method to reveal and investigate their key points and outcomes.

The results of the relevant studies were summarized and interpreted to be placed in the context of the target problem. The systematic comparison of the articles allowed for the detection of common themes and integrating them to address the PICO question. The data items included 15 articles with their abstracts, full-texts, as well as appendices. The data synthesis also involves the assessment of limitations, opportunities, and future research prospects.

Results

Study Selection

The study appraisal process identified 236 articles in CINAHL and 358 articles in Medline. The duplicates were excluded, 192 potential studies were screened, and 146 articles were eliminated after the title and abstract screening. Twenty-one studies were further excluded after the screening of their full texts and 10 more excluded after data extraction. In total, this systematic review contains 15 articles, each of which discusses one or more aspects of the problems in the long-term care environment related to unnecessary hospitalizations, delays in care, patient and family satisfaction, and the effectiveness of APRNs in long-term care.

Study Characteristics

The included studies were appraised with regard to their research design, quality of data obtained, and participants in terms of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) appraisal method. All 15 studies were of high quality: the majority of them contain level II evidence. Also, the sample selection is clearly described in each of the studies, which allows concluding that the authors’ statements can be attributed to a certain category of patients in other settings. The general characteristics of the studies include the incorporating of APRNs roles in long-term care and the ways their functions affect patient outcomes.

Of 15 studies, 11 used a qualitative design, including Dwyer et al. (2017) (Donabedian’s process), Lee et al. (2016) (survey), Mullaney et al. (2017) (content analysis), Rantz et al. (2017a) (descriptive analysis), while Carter et al. (2016), Oliver et al. (2014), Ploeg et al. (2013), Popejoy et al. (2017) (qualitative descriptive design ), and Vogelsmeier et al. (2018) were review studies based on a grounded theory, and there were two case studies by Cole (2017) and Ono et al. (2015). A quantitative design was applied by Carter et al. (2016) (two-phase sequential mixed design), Lacny et al. (2016) (controlled before-after design), Rantz et al. (2017b) (prospective, single-group intervention design), and Rantz et al. (2018) (a 2-group comparison analysis). The most common sample selection method was the strategic focus on sites with APRNs. The majority of the studies have no demographic information about participants, mentioning only how many participated (e.g., number or percentage) (Lacny et al. (2016), Dwyer et al. (2017), Devereaux Melillo et al. (2015), Ono et al. (2015), Ploeg et al. (2013), Rantz et al. (2017a), and Rantz et al. (2017b). The rest of the studies were not associated with specific participants yet contribute to the review. The sampling method used in these studies was based on the inclusion of nursing homes that face reducing hospitalizations and those without any progress.

As for settings, 5 out of 15 studies focused on 16 nursing homes each (Popejoy et al. (2017), Rantz et al. (2017a), Rantz et al. (2017b), Rantz et al. (2018), Vogelsmeier et al. (2018). Ploeg et al. (2013) and Carter et al. (2016) involved 4 nursing homes each, while Ono et al. (2015), Mullaney et al. (2017), Dwyer et al. (2017), and Cole (2017) included one nursing home each. The nursing homes were in different countries: 4 in Canada, 1 in Japan, 1 in Australia, and the remainder were in the United States. The LTC environment with Medicare or Medicare and/or Medicaid recipients was targeted by Oliver et al. (2014), Lee et al. (2016). Lacny et al. (2016) and Devereaux Melillo et al. (2015) did not identify the number of settings, yet all of the studies focused on long-term care environments.

Of 15 studies, 2 used focus groups (Carter et al., 2016, Mullaney et al., 2017), 7 – interviews (Ploeg et al., 2013; Mullaney et al., 2017; Dwyer et al., 2017; Cole, 2017; Rantz et al., 2017b; Rantz et al., 2017a; and Rantz et al., 2018), and 3 – data extraction from charts and documents (Oliver et al., 2014; Ono et al., 2015; and Lacny et al., 2016). Medicare claims were utilized by Lee et al. (2016) and Devereaux Melillo et al. (2015), and electronic databases with extensive medical data related to the topic were used to collect information by Vogelsmeier et al. (2018). One study referred to a virtual learning management system that contained data about patients and procedures to collect data weekly (Popejoy et al., 2017).

In order to properly evaluate the quality of the studies, the Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Research Evidence Appraisal tool was applied. Four studies were marked as II, B due to their experimental design, consistent findings, and appropriate measurement methods (Appendix 1) (Rantz et al. (2017b), Rantz et al. (2017a), Oliver et al. (2014), and Devereaux Melillo et al. (2015). 6 studies received III, B grade, including Ploeg et al. (2013), Lee et al. (2016), Dwyer et al. (2017), Popejoy et al. (2017), Rantz et al. (2018), and Carter et al. (2016). Ono et al. (2015) (V, C), Oliver et al. (2014) (II, A), Mullaney et al. (2017) (I, B), Lacny et al. (2016) (II, C), and Cole (2017) (V, B) received different grades (Appendix 1). Case studies were regarded as less reliable studies, and mixed-method design research by Mullaney et al. (2017) was considered as high quality.

Risk of Bias Within and Across Studies

There are five main points that can pose the risk of bias, which should be taken into account while interpreting the results of this systematic review (Table 1). The limited sample size, study sites, and restricted data are the biases that limit the generalizability of the outcomes. There are 2 studies with a high risk for the sample size factor, and 2 more studies present an unclear risk. Two studies have the unclear risk for bias due to patient selection. Two studies are marked as having high risk due to study sites. Limited data bias refers to insufficient and ambiguous data found across and within the obtained studies (3 studies). Due to bias, the outcomes obtained from the reviewed studies should be interpreted with caution. Two studies have a high risk of confirmation bias, and 2 other studies are defined as having uncertain risk.

Table 1. Risk of bias assessment based on Quadas tool

The results obtained from the literature analysis are grouped according to themes identified in the studies. These themes centered around the key topic pertaining to the effectiveness of APRNs in LTC. These themes include the impact on hospitalizations or hospital transfers, quality of care, family and patient satisfaction, and healthcare costs.

Hospitalizations

The evaluation of the structural and outcome dimensions of APRNs demonstrates that they respond to early symptoms of patients and intervene accordingly to avoid unwanted hospitalizations. In two studies by Rantz et al. (2017a, 2017b), the presence of an APRN in the LTC reduced hospitalizations by 40% in one study and 30% in another one; in addition, emergency department (ED) visits were reduced by 57% in one of the studies and 54% in another, considering that it is a part of the 30% study. According to Oliver et al. (2014), the range of hospitalizations reduced from 25.9 to 18.1 per 1000 persons a year, when an APRN was working at LTC facility. Reductions in hospitalizations were attributed to increased communication. Mulaney et al. (2017) reported a decrease in unwanted hospitalizations by 25% due to setting proper care goals and implementing advanced practices by APRNs, such as staff and patient education on care quality improvement as well as pre-and post-operative procedures. It is also noted that the more frequently the APRN communicates with families the lower the incidence of hospitalizations. Out of 87 participants, only 10 patients accounted for 14 hospitalizations, while the remaining 77 had no readmissions.

Work in the hospital avoidance service is regarded by Dwyer et al. (2017) as the one that is flexible and dynamic compared to traditional older adult care that is still practiced in many clinics across the US. Qualitative studies found that APRNs fill an important role (Dwyer et al., 2017; Lacny et al., 2016; Oliver, Pennington, Revelle, & Rantz, 2014) in reducing hospitalizations. Dwyer et al. (2017) and Lacny et al. (2016) provide descriptive findings that support the potential of APRNs to decrease hospital transfers. These researchers determined that the decreases occurred by upskilling staff, introducing collaborative care plans, and communication and relationship building with patients improves care quality.

The positive impact of advanced nursing planning may also be noted with regard to mortality risk assessments (MRAs), where patient and family discussions play a significant role (Mullaney et al., 2017). In case a patient was classified as at risk of developing complications, the meetings with care providers were more frequent to explain potential health deterioration and comorbidity and identify elimination strategies, which reduced hospitalizations (Lacny et al., 2016; Rantz et al., 2018). Two of the studies specifically evaluated the decrease in hospital stays based on experiments (Lacny et al., 2016; Mullaney et al., 2017), while two others selected the observation of the already existing settings (Oliver et al., 2014; Ploeg et al., 2013). These studies found that the difference in hospitalizations largely depends on the number of patient health discussions: the more meetings, the fewer hospital admissions.

Another area that should be uncovered in the context of APRNs operating in the LTC setting is the barriers existing in this field. These barriers include limited or reduced practice which reduces one or more elements of APRN practice, this varies by state. States that approved the authority of APRNs to provide full practice have lower hospitalization levels compared to states that have limited practice scopes (Oliver et al., 2014). The health outcomes of Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries were more stable in cases where they were referred to an APRN instead of the primary care physician or registered nurse. No percentages are reported in these studies. Ono et al. (2015), Devereaux Melillo et al. (2015), and Mullaney et al. (2017) found that the collaboration of physicians with the APRNs reduces the number of hospitalizations, which is caused by better daily care management offered to the patients of various care facilities.

Patient and Family Satisfaction

APRN presence in LTC is associated with increased patient and family satisfaction. The results obtained by Carter et al. (2016) are representative of the link between the work of APRNs and improved access of patients to primary care. A secondary analysis of 143 respondents showed that affordability, accessibility, accommodation, and acceptability are the main criteria of satisfaction. In particular, patients, their families, and nurses pinpointed the positive impact of APRNs due to their presence in LTC, which is reported by 1 study but not measured numerically (Carter et al., 2016).

Cole (2017) also found that a full-time interaction of APRNs with the staff leads to greater patient satisfaction, which is caused by better collaboration between interdisciplinary team members and communication with patients. This study used a case study method and exemplifies a patient who was admitted to the nursing home at the age of 93 and died at 98 surrounded by 24-hour care and staff that was well-aware of her needs. Similar findings are also noted by Ploeg et al. (2013), who emphasized the role of interdisciplinary cooperation in LTC. The sample consisted of 35 patients and their families who were surveyed, and the findings demonstrated that the joint efforts between patients, families, and NPs allowed for the provision of education to patients and their families, thus increasing their awareness of potential adverse health issues. This increased awareness allowed for earlier detection of problems in order to avoid them.

Healthcare Costs

Reduced healthcare costs are another important aspect that is targeted by this systematic review. Cole (2017) and Rantz, Birtley, Flesner, Crecelius, and Murray (2017a) measured billing, budgetary considerations, and reimbursement associated with medical costs. These researchers found that in LTC settings, APRNs have the opportunity to provide benefits associated with cost-saving, which markedly increased patient and family satisfaction levels. However, not all of the included studies revealed similar results, the author’s analysis shows that costs of emergency transfers may slightly increase, as shown by the point estimates of the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio. It may be caused by the uncertainty in the distribution of costs and effects in the nurse practitioner- family physician (NP-FP) model, which Lacny et al. (2016) aligned with the impossibility of making definite conclusions about the effectiveness of APRNs in the LTC. The researchers noted that such an outcome cannot be merely linked to the role APRNs perform since it is the responsibility of a team of care providers when it comes to hospitalizations and treatment. Based on 1322 subject observations that were aimed to understand how the primary care practice model affects patients in the LTC, Devereaux Melillo et al. (2015) stated that further research should investigate a larger sample and conditions to answer the question of the effectiveness of APRNs in the LTC setting.

In nursing homes, the collaboration of APRNs and physicians is considered to be beneficial in terms of reducing care costs. One of the appraised studies by Lee et al. (2016) can be identified as supporting the general evidence on the economic efficiency of such joint services, which is expressed in greater visits and costs of patients managed by MDs only, and these results that demonstrate that the collaboration with APRNs reduces costs are also discussed by Mullaney et al. (2017). A limitation of these studies, however, is that costs were not specifically measured statistically. On the contrary, according to Ono et al. (2015), multivariate analysis shows that the inclusion of APRNs promotes a lower frequency of patient hospitalizations due to preventative strategies: they reduced from 45.8% before the APRN intervention to 30.1% after APRN intervention. Lacny et al. (2016) focused on analyzing the cost-effectiveness of implementing APRNs in care practice. Based on the controlled before-after design, the author revealed 26% and 21% cost-effectiveness in internal and external family physician-only control groups in the study accordingly (Lacny et al., 2016). The cost-effectiveness was defined as the comparison of implementing APRNs to both of the mentioned conditions that mean outpatient and inpatient settings. In turn, Dwyer et al. (2017) who focus on this dimension of care stress that public policy should encourage the APRNs and assist them with developing their skills and knowledge as their work is cost-effective and positive to patient health status.

Quality of Care

Among other results achieved by APRNs providing their services in long-term care facilities include better assessment, faster recovery, and more integrated treatment. The effectiveness of APRNs in patient assessment is a finding in the study by Popejoy et al. (2017), which is also closely associated with ill patient management and a more focused treatment approach. All 16 nursing homes involved in this qualitative descriptive study reported improvements in discussing care comfort and limiting some unnecessary services when APRNs were part of the care. Most importantly, nutrition, hydration, mobility, and communication were noted as the factors that supported the success of advanced practices, as stated in one study using the Missouri Quality Initiative (MOQI) (Rantz et al., 2017b). In many reviewed studies, whole access care is declared to be paramount to ensure that care professionals can use their authority and knowledge to the full extent. The availability of APRNs on a daily basis promotes patients to have quicker recovery as well as the opportunity to reach them in an almost instantaneous manner.

Some of the studies from the systematic review place an emphasis on comparing the potential contribution of APRNs and physicians to understand how to improve current practices in LTC facilities. The review of Medicare beneficiaries’ information found that no difference existed between APRNs and physicians when ADL performance deficits were analyzed. The analysis revealed transfer (15.3% for MD versus 15.1% for APRN), self-dressing (9.1% versus 10.6%), and independent eating (31.4% versus 36.9%). Such a formulation is used by the author, who aimed to compare the effectiveness of the mentioned specialists in terms of various aspects. Both of these care providers assessed patient demographics and ADL deficits and managed other staff members, which shows their common responsibilities (Devereaux Melillo et al., 2015).

Discussion

Summary of the Evidence

The studies included in this systematic review proved to be valuable and thought-provoking to integrate the evidence and contribute to the theory of nursing practice. The majority of the studies contained appropriate sample selection, methodology, and well-organized presentations of the results and discussions. The logical flow as well as the identification of potential biases, limitation, and importance to practice were also specified by the studies.

The outcomes of this systematic review allow answering the stated PICO question along with the identified sub-questions. This review demonstrated that APRNs are effective in reducing hospitalizations and costs and improving quality of care and patient and family satisfaction in LTC settings. These findings are supported in the literature, in particular, by some of the reviewed studies (Donald et al., 2013; Moran, et al., 2016). The key indicator that is representative of APRN effectiveness is the reduced rates of hospitalizations. The patients who are referred to APRNs have reduced chances of being transferred to the emergency department (Deraas, Berntsen, Jones, Førde, & Sund, 2014). The reduction in hospitalizations and transfers is mainly attributed to advanced practice nurses early and more comprehensive consideration of clients’ signs and symptoms which results in the initiation of early interventions. The key idea noted in the mentioned studies is that the mechanism of referring patients directly to the APRN is proved to be advantageous for decreasing unnecessary hospitalizations. APRNs with good and advanced skills are likely to facilitate the challenging care environment, both to patients and nurses who may encounter complicated care related and ethical situations.

The additional benefit provided by the work of these APRNs is the potential to decrease the current financial burden experienced by a lot of patients, especially those of older age. APRN care in other environments such as hospitals and primary care offices has been associated with reduction in healthcare costs overall. These reductions are attributed to increased attention to patient needs, leading to less complications and comorbidities (Levinson, 2013). The implementation of APRNs into LTC facilities reduces unnecessary hospitalizations and interventions, thus preserving patient savings (Rantz et al., 2018). APRN care, in one study, was associated with slight increase in costs, which was probably caused by the emergency department services and , therefore, not truly of reflection of APRN care. Nevertheless, the suggestion was made by the researchers that APRNs reduce care costs based on a conducting a more comprehensive patient evaluation and prescription of necessary treatment only. There is a lack of studies comparing APRN care to other levels of healthcare providers (e.g., physicians, physician assistants) in LTC.

APRN care in LTC is associated with increased family and patient satisfaction. Quality of care is improved due to faster recovery improved and timely patient assessment and development of treatment plans. Other studies demonstrate that APRNs’ are beneficial not only in LTC but also in such facilities as hospitals and in primary care environments. Dobbins (2016) notes that with the complexity of care that tends to increase due to aging and disease prevalence, the positive impact of APRNs increases. The current fragmented healthcare system presents challenges, and ARPNs working in collaborative practice across teams can significantly improve the fragmentation. The efforts of APRNs are relevant to the needs of older adult population. The Transitional Care Model (TCM), which focuses on patient and family health improvement by enhancing care, is one of the most feasible tools to change the existing environments via interdisciplinary cooperation (Hirschman et al., 2015). APRNs should take more initiative to explore ways in which to improve services via adopting advance care planning and paying attention to patient preferences and feedback.

Patient and family satisfaction is another dimension of the given problem that was also supported in a number of the studies, both qualitative and quantitative. The closer interaction with patients and their families allowed creating trust and openness, which were used by care professionals as the tool to better learn patients’ needs and preferences (Donald et al., 2013). Since the study by Carter et al. (2016) discussed the concept of access via five dimensions, such as affordability, acceptability, availability, accessibility, and accommodation, the data can be regarded comprehensive and reliable. At the same time, the collaboration between the care team was regarded as one more essential point of increasing patient satisfaction. In general, patients value APRNs listening skills, openness, and honesty in interaction. It should be emphasized that patient satisfaction is subjective, depending on individual experience, expectations, and needs.

Implications for Advanced Practice Nursing

Not only are APRNs responsible for effective care but physicians, nurses and other team members are equally involved. Therefore, further research is required to explore the roles of team members and how best APRNs can be used on these teams and how to promote their cooperation under the supervision of APRNs. Griffin and McDevitt (2016) also emphasized the positive role of APRNs in the emergency care department in providing safe and high-quality services, which increases patient satisfaction. Thus, not only will this research impact LTC settings but also other environments will benefit from having APRNs.

Limitations

The generalizability of the findings of this systematic review is restricted by its limitations as well as those specified by the analyzed studies. The majority of the included studies investigated only one area of patient care quality improvement such as hospitalization decrease while omitting the associated factors such as morbidity and mortality rates. One of the overt limitations refers to excluding those patients who died during the studies and their inclusion may change the findings and conclusions. The second issue is the focus on a few studies (n=15) without taking into account more studies and a more extensive sample, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Ultimately, it should also be stated that a single reviewer selected and appraised these studies, while it is expected to be done by two independent researchers. These limitations create the prospects for further studies in the given field of interest. Such strong points of the studies as evidence collection and analysis as well as a variety of methods used contribute to enriching the literature.

The barriers such as restrictions in some states to the performance of APRNs or physician-related issues that are faced by APRNs in the course of assessing patients and assigning necessary interventions are the first gap. The second gap refers to a lack of studies that separate the impact of APRNs from that of the team. In many cases, it is not clear whether APRNs acted directly and independently or within a team. In addition, there is a need to conduct comparative studies looking at APRNs, physician Assistants., and physicians in the LTC.

The recommendations for further research are associated with exploring the impact of APRNs in LTC in the context of their performance, care dimensions, and patient perceptions. It is important to determine the views of patients and examine their attitudes, which can be utilized to adjust advanced services. A determination of which specific actions taken by APRNs lead to decrease hospitalizations and readmissions of older adult patients is necessary. Such studies should include the interaction with staff members and the impact on continuous care improvement and professional development. The studies exploring the economic impact of introducing APRNs in the LTC are also needed to ensure the cost-effectiveness of care services.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this review provides valuable insights into the role of APRNs in treating patients in LTC settings. The systematic review integrated the recent evidence on their effectiveness in reducing patient hospitalizations and costs from nursing homes. It is found that APRNs role involves increasing staff awareness of specific patient needs, providing education to enhance nurses’ skills, and managing all the procedures and processes in LTC settings. The patients who interacted with APRNs reported increased satisfaction, and their families also noted that the improved communication was beneficial. While there still needs to be further studies to evaluate cost-effectiveness most of the studies point to the potential for a reduction in healthcare costs.

References

Carter, N., Sangster-Gormley, E., Ploeg, J., Martin-Misener, R., Donald, F., Wickson-Griffiths, A.,… Schindel Martin, L. (2016). An assessment of how nurse practitioners create access to primary care in Canadian residential long-term care settings. Nursing Leadership (1910-622X), 29(2), 45-63.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). The state of aging and health in America 2013. Web.

Code of Federal Regulations: Section 483.70. (2018). Web.

Cole, M. S. (2017). Case study: Realizing the value of nurse practitioners in long-term care. Nursing Leadership, 30(4), 39-44. doi:10.12927/cjnl.2017.25450

Deraas, T. S., Berntsen, G. R., Jones, A. P., Førde, O. H., & Sund, E. R. (2014). Associations between primary healthcare and unplanned medical admissions in Norway: A multilevel analysis of the entire elderly population. BMJ Open, 4(4), e004293.

Devereaux Melillo, K., Remington, R., Abdallah, L., Gautam, R., Lee, A. J., Van Etten, D., & Gore, R. J. (2015). Comparison of nurse practitioner and physician practice models in nursing facilities. Annals of Long Term Care, 23(12), 19-24.

Dobbins, E. H. (2016). Improving end-of-life care: Recommendations from the IOM. The Nurse Practitioner, 41(9), 26-34.

Donald, F., Martin‐Misener, R., Carter, N., Donald, E. E., Kaasalainen, S., Wickson‐Griffiths, A.,… DiCenso, A. (2013). A systematic review of the effectiveness of advanced practice nurses in long‐term care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(10), 2148-2161.

Dwyer, T., Alison, A., Dolene, D., Darren, D., Craswell, A., Rossi, D., & Holzberger, D. (2017). Evaluation of an aged care nurse practitioner service: Quality of care within a residential aged care facility hospital avoidance service. BMC Health Services Research, 17, 1-11.

Evans, G. (2011). Factors influencing emergency hospital admissions from nursing and residential homes: Positive results from a practice‐based audit. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 17(6), 1045-1049.

Griffin, M., & McDevitt, J. (2016). An evaluation of the quality and patient satisfaction with an advanced nurse practitioner service in the emergency department. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 12(8), 553-559.

Harris-Kojetin, L., Sengupta, M., Lendon, J., Rome, V., Valverde, R., & Caffrey, C. (2019). Long-term Care Providers and Services Users in the United States, 2015–2016 (Vol. 43, Ser. 3) (United States, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). National Center for Health Statistics.

Hirschman, K. B., Shaid, E., McCauley, K., Pauly, M. V., & Naylor, M. D. (2015). Continuity of care: The transitional care model. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 20(3). Web.

Holly, C., Salmond, S., & Saimbert, M. (2011). Comprehensive systematic review for advanced practice nursing. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Ibrahim, J. E., Bugeja, L., Willoughby, M., Bevan, M., Kipsaina, C., Young, C., … Ranson, D. L. (2017). Premature deaths of nursing home residents: An epidemiological analysis. Medical Journal of Australia, 206(10), 442–447.

Lacny, S., Zarrabi, M., Martin ‐ Misener, R., Donald, F., Sketris, I., Murphy, A. L.,… Marshall, D. A. (2016). Cost-effectiveness of a nurse practitioner-family physician model of care in a nursing home: Controlled before and after study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(9), 2138-2152.

Lee, A. J., Gautam, R., Melillo, K. D., Abdallah, L. M., Remington, R., Van Etten, D., & Gore, R. (2016). A Medicare current beneficiary survey-based investigation of alternative primary care models in nursing homes. Research in Gerontological Nursing, 9(3), 115-122.

Levinson, D. R. (2013). Medicare nursing home resident hospitalization rates merit additional monitoring. Web.

Moran, K. J., Burson, R., & Conrad, D. (2016). The doctor of nursing practice scholarly project (2nd ed.). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Publishers.

Mullaney, S. E., Devereaux Melillo, K., Lee, A. J., MacArthur, R., Embuldeniya, G., Kirst, M.,… Wodchis, W. (2017). The association of nurse practitioners’ mortality risk assessments and advance care planning discussions on nursing home patients’ clinical outcomes. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Ubiquity Press.

Oliver, G. M., Pennington, L., Revelle, S., & Rantz, M. (2014). Impact of nurse practitioners on health outcomes of medicare and medicaid patients. Nursing Outlook, 62(6), 440-447.

Ono, M., Miyauchi, S., Edzuki, Y., Saiki, K., Fukuda, H., Tonai, M.,… Murashima, S. (2015). Japanese nurse practitioner practice and outcomes in a nursing home. International Nursing Review, 62(2), 275-279.

Ploeg, J., Kaasalainen, S., McAiney, C., Martin-Misener, R., Donald, F., Wickson-Griffiths, A.,… Taniguchi, A. (2013). Resident and family perceptions of the nurse practitioner role in long term care settings: A qualitative descriptive study. BMC Nursing, 12(1), 24-35.

Popejoy, L., Vogelsmeier, A., Galambos, C., Flesner, M., Alexander, G., Lueckenotte, A.,… Rantz, M. (2017). The APRN role in changing nursing home quality: The Missouri quality improvement initiative. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 32(3), 196-201.

Rantz, M. J., Birtley, N. M., Flesner, M., Crecelius, C., & Murray, C. (2017a). Call to action: APRNs in U.S. nursing homes to improve care and reduce costs. Nursing Outlook, 65(6), 689-696.

Rantz, M. J., Popejoy, L., Vogelsmeier, A., Galambos, C., Alexander, G., Flesner, M.,… Petroski, G. (2017b). Successfully reducing hospitalizations of nursing home residents: Results of the Missouri quality initiative. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 18(11), 960-966.

Rantz, M. J., Popejoy, L., Vogelsmeier, A., Galambos, C., Alexander, G., Flesner, M.,… Petroski, G. (2018). Impact of advanced practice registered nurses on quality measures: The Missouri quality initiative experience. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 19(6), 541-550.

The 2018 Florida Statutes, (2018). Chapter 400. Web.

Vogelsmeier, A., Popejoy, L., Crecelius, C., Orique, S., Alexander, G., & Rantz, M. (2018). APRN-conducted medication reviews for long-stay nursing home residents. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 19(1), 83-85.