This white paper explores the use of information technology for quality improvement in the primary health care setting. Accustomed to addressing the needs of the health industry, which is the audience for this paper, we developed the findings from a targeted review of published reports and expert analysis. Comprehensively, we learned three lessons regarding the use of health information technology for quality improvements. The first one was the importance of leadership in implementing health information technology. The second one was the realization that most health stakeholders would realize the immense benefits of information technology when they understand their contributions to quality improvements. The third lesson we learned was the need to have a dedicated quality improvement team that would collaborate with other members of the organization to improve the use of health information technology in the primary care setting. The third lesson we learned was the importance of using health information technology to inspire quality improvements in the organization. These lessons are important for clinicians, facilitators and practice leaders in the health sector because they are instrumental in promoting quality improvements in the primary care setting.

Introduction

For a long time, people have used information technology in different economic sectors. The quest to make a profit and improve operational processes has particularly seen an increase of its adoption in for-profit economic sectors. Its use in the health care sector has not matched up to its popularity in other aspects of political, social, or economic development. Consequently, the research on the adoption of information technology tools in the health care practice is relatively new, all over the place, and partially underdeveloped. This is true for the United States (US) health care system, which has been dogged by many problems stemming from the stagnancy of health care quality (for certain segments of the sector), lack of adequate access to health care services for all populations, and inefficiencies in the delivery of service, just to mention a few.

Based on the aforementioned problems, revitalizing the primary health care system could emerge as a solution to addressing some of these health care problems. Doing so could require the effective implementation of health information technology. Health information technology simply refers to the use, or adoption, of information technology tools in the health care practice (Werder, 2015). Broadly, this concept refers to the use of computerized systems to support health functions (Werder, 2015). Generally, health stakeholders have adopted this concept within the framework of securing the exchange of health information among the relevant parties (Agency for Health Care Research and Quality, 2014). Research evidence on the same issue has shown that the adoption of information technology tools, such as the use of electronic health records (EHR), in the health practice is the most promising tool for improving the quality of health care services.

Additionally, in the context of this paper, quality improvements involve using data and feedback in the service delivery process, monitoring/tracking or assessing the quality of service delivery for a specified time, and making changes in the service delivery process to improve health care quality. In this paper, we also generally use the concept of primary care to refer to the provision of health care at a basic level. Stated differently, this is the type of health care given by health practitioners at the first point of contact with a patient. It may often lead to continued care in the end.

Based on the works of Lyons and Luginsland (2014), in this white paper, we identify specific health IT tools for improving quality improvements, describe factors that promote primary care practices and outline the unique requirements that health stakeholders should consider to enjoy the benefits of health information technology in improving quality outcomes in the primary care setting. Following these objectives, this paper points out that health information technology could eliminate the inefficiencies of health care service delivery and promote improved quality in primary care delivery. To come up with this finding, we interviewed two health practitioners and sought the insights of ten nationally recognized IT experts who specialize in the adoption and use of health information technology in the same sector. We also gathered insights and recommendations from previously published work, such as journals, books, and credible online websites. Our findings of the previous approaches in the use of health information technology for quality improvements in the primary care setting appear below.

Previous Approaches

In the past few years, medical policies have often supported the adoption of health information technology in the health care practice. For example, in 2009, the Federal Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act provided incentives to health care service providers to use health information technology to improve service delivery in the practice (Mathematica Policy Research, 2015). The American Recovery and Investment Act provides the framework to do so.

Legal efforts to improve the use of information technology tools in the health care practice have mostly focused on tracking and reporting on the performance of different health care facilities regarding their quality improvement processes. Some of these tools have been useful in e-prescribing processes and in the implementation of decision support processes. For example, in 2014, the Medicare and Medicaid programs allocated more than $19 billion to offer incentives to health stakeholders to adopt health information technology (Mathematica Policy Research, 2015). The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act 2010 also emphasized the role of incorporating health informatics tools in its strategic plan to encourage health stakeholders to improve their quality initiatives (Werder, 2015). The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology has also joined the fray and established more than 62 regional centers to support different stakeholders who may want to implement information technology in their institutions (Mathematica Policy Research, 2015). Their work has focused on improving the quality of health care services in underserved communities. Some of these health agencies have also provided incentives to health care service providers by providing them with grants. For example, between 2004 and 2010, the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (2014) gave more than $300 million in grants to different community stakeholders who wanted to understand how to implement health information technology in their practice.

Despite the increased support from health agencies and government stakeholders regarding the adoption of health information tools in their practice, most of these systems remain relatively underused or inefficiently used by health care practitioners. Conversely, they have failed to achieve their true objectives. Part of the problem stems from the resistance to use information technology tools in primary care (Langley & Beasley, 2007). In other words, the adoption of this concept is relatively new in this aspect of health care delivery. The result is the inability of new IT users to integrate information technology tools in quality improvement processes. Some practitioners also do not understand that the use of information technology tools does not automatically translate to the improvement of quality in primary care (Langley & Beasley, 2007). Others fear the cost of adopting and implementing health information technologies because most of the costs of doing so are recurring. The diagram below affirms this argument by showing that 69% of the cost of implementing health information technology is recurring.

Based on the above pie chart, the percentage of recurring costs is high because of licensing fees, support fees and maintenance fees (in terms of hardware updates, employee training, and such-like costs) (Mathematica Policy Research, 2015). The opportunity cost may suffice through the process of accounting for productivity loss during implementation, while one-off costs may arise because of implementation and training processes. These factors combined, it is pertinent for health stakeholders to carefully consider the resources required in implementing health information technology; whether they have these resources, and, more importantly, how these resources would contribute to quality improvements in their organizations. Indeed, the use of health information technology requires thoughtful analysis and purposeful thinking to improve the standards of health care delivery.

Additionally, health care facilities may need to hire specialized practitioners to integrate such skills in their practice. They may also need to be smart about their resource allocation standards, all which would entail incremental costs in service delivery practices through more training that is vigorous, increased capital inputs and more time required in primary care delivery (Langley & Beasley, 2007). Finally, some health stakeholders do not understand that although they stand to benefit from the adoption of health information technology, most of the costs associated with the same are mostly borne by the primary care practice. Additionally, people who are not in the primary care practice, such as financiers and patients, enjoy much of the benefits accrued from the adoption of health information technology (Langley & Beasley, 2007). Although these barriers exist, some primary care facilities have devised ways of benefitting from the adoption of health information technology in their practice.

New Findings

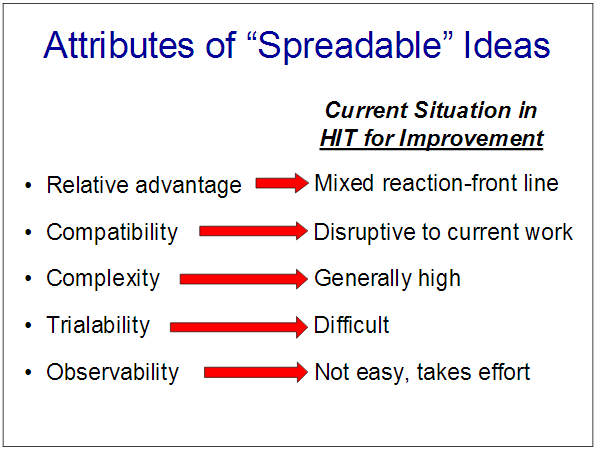

Although few people who could dispute the potential benefits of health information technology on quality improvements in the primary care setting, most of the organizations which have failed to enjoy the benefits of health information technology have failed to understand what it takes to benefit from these tools. Our research revealed that most of them gave up when they encountered objections, or resistance, during adoption. Five main attributes – relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, and observability sum these objections. Our expert findings revealed that most people are scared of these objections, although health information technology rarely exhibits these attributes. Our literature review also affirmed the same findings, as highlighted in the table below which sums up these objections as a detailed description of HIT for improvement.

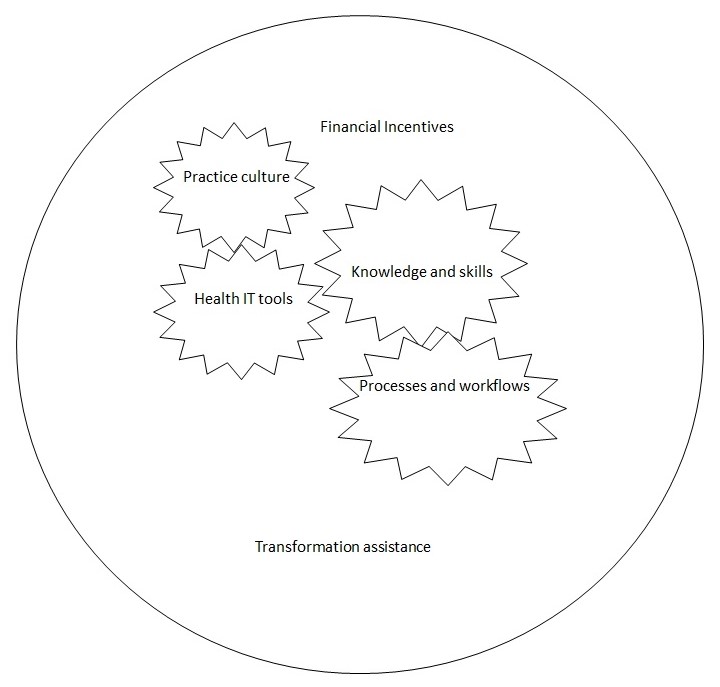

Our literature review and expert analysis also revealed that integrating health information technology in the primary care practice requires the setting up of four key pillars of implementation – none of which can stand alone.

One pillar is a strong cultural commitment to use information technology tools to improve quality improvements in the primary care setting. The second pillar involves developing and using high-functioning information technology tools to facilitate the tracking, analysis and monitoring of health data. The third pillar involves having a strong clinical team that appreciates health information technology and that knows how to use such technology for quality improvement. Finally, the last pillar of our analysis involved setting up practice flows and workflow processes that incorporated the effective use of information technology. The diagram below highlights these core pillars of health information technology and their integration framework for quality improvements in the primary care setting.

Having a culture that appreciates the importance of health information technology comes from having a strong health leadership structure in the organization. Leaders could be lead physicians, medical directors, or people with authority. The point is that they should be in a position to hold other people accountable for their actions. An organization that has effectively built a culture of health IT would not only use the technology for one project, but make sure that its use prevails through continuous projects as well.

The above-mentioned health IT tools could refer to different technologies, such as electronic health registers, registries, decision support systems, and health information exchange (among others) (Mathematica Policy Research, 2015). These tools are important in tracking and measuring information with the goal of improving efficiency in the health structure and improving patient health outcomes. Knowledge and skills are also important in extracting and analyzing information for the proper execution of quality improvement initiatives. Such skills and knowledge are important in redesigning workflow processes to include quality improvement activities. The practice processes and workflows are beneficial in providing feedback to clinicians and helping them identify areas that need further improvement, or focus. Finally, financial incentives are important in the implementation of health information technology because they help to offset the cost of clinician training and staff time spent on quality improvement initiatives.

Conclusion

To recap, in this paper, we conducted a targeted analysis of how health information technology could be beneficial to the provision of primary care in America. From this research, we identified different publications that focused on primary care and the improvement of health care quality in the primary care setting. Additionally, we convened a technical panel of ten nationally recognized experts who have tremendous knowledge in primary care service delivery. This technical panel offered immense knowledge on the use of health information technology for quality improvements in the clinical care setting. Our findings showed that information technology tools could offer immense benefits to quality improvements in primary care. However, our targeted review of published reports and expert analysis highlighted important lessons we need to adhere to when implementing health information technology in quality improvements.

The first lesson we learned was the importance of leadership in implementing health information technology. The second lesson learned is that true transformation in the health sector would only occur if people understand the real benefits of health information technology in quality improvements. The third lesson we learned was the need to have a dedicated quality improvement team that would collaborate with other members of the organization to make use of health information technology to improve quality of care in the primary setting. The third lesson we learned was the importance of using health IT to inspire quality improvements in the organization. These lessons are important for clinicians, facilitators and practice leaders because they are instrumental in promoting quality improvements in the primary care setting.

References

Agency for Health Care Research and Quality. (2014). Future directions for the national healthcare quality and disparities reports. Web.

Langley, J., & Beasley, C. (2007). Health information technology for improving quality of care in primary care settings. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Lyons, J., & Luginsland, J. (2014). White papers and beyond: reflections from former grants officers. The industrial-organizational psychologist, 52(2), 129-135.

Mathematica Policy Research. (2015). Using health information technology to support quality improvement in primary care. Princeton, NJ: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Werder, M. (2015). Health information technology: A key ingredient of the patient experience. Patient experience journal, 2(1), 143-147.