Decision making is the process of developing an answer to a particular problem. The dichotomy of individual and group decision making is paramount for nursing due to the fact that professional choices directly influence people’s wellbeing and life (7. Shaban, 2015). Administering the wrong dosage of a drug could lead to lethal outcomes, which stresses the importance of this issue. The problematic nature of decision making is imbued with the nature of the individual process of forming a solution that is subject to bias and discrepancy and team dynamics that often involve frictions and arguing over treatment (1. Banning, 2008).

There is also an array of internal and external factors that impede or boost decision making in nursing practice, which makes the research in this sphere vital. Historically, decision making was outside of the nurses’ area of expertise, as the profession was considered auxiliary to other medical specialists.

According to Shaban (2015), presently, the nursing profession has developed an exceptional capacity for making standalone decisions and influencing the development of a compromise within a group. Given such role advancement, it is critical that major instruments and factors of decision making are reviewed and continually updated.

Yet, given the variety of models, there persists a certain ambiguity in the literature about where group decision making is more effective than individual frameworks such as O’Neill’s clinical decision making model. In light of the above, the aim of this paper is to review the modern and historical views of scholars on decision making in the nursing sphere in the context of the individual-group dichotomy and find implications for present and future practice. The objectives of the current research are as follows:

- Identify the main constituents of O’Neill’s clinical decision making model;

- Research factors influencing group decision making model;

- Compare and contrast O’Neill’s clinical decision making model and group decision making in terms of effectiveness;

- Draw conclusions and implications.

Background

The process of making a decision in nursing has fallen under the scope of scholarly research in the last several decades. The core constituents of this cognitive process are that results in selecting appropriate actions for a given problem include five elements (10. Tiffen, Corbridge, & Slimmer, 2014). Among those elements are the identification of a problem, alternatives, information evaluation and processing, and decision implementation and evaluation of consequences.

In various occasions, the basic decision making process may be subject to the influence of a variety of factors that facilitated the emergence of variations in understanding and guiding this process. The core goal of such scientific effort was the enhancement of quality of an ultimate choice (10. Tiffen et al., 2014). Many researchers agree that the emerged models of decision making in nursing are impractical in one way or another and require certain adjustments to both suits the needs of time and advancing technology.

In light of this, certain frameworks gained increased attention as well as criticism (10. Tiffen et al., 2014). Among them are clinical decision making model authored by O’Neill and group decision making theory, which is an accumulative set of practices formed naturally and independently documented and discussed by several researchers. The scientific debate persists in relation to whether individual models such as O’Neil’s could outcompete group model in consideration of all their advantages and disadvantages (1. Banning, 2008).

Literature Review

Clinical decision making evolved under the influence of the shift in the nursing profession that allowed these professionals to advance their role in hospitals and provide quality of care in a new dimension. Previously, the administration of drugs and the evaluation of a patient’s disease progression was majorly a job of physicians (10. Tiffen et al., 2014). Nursing personnel was preoccupied with tasks connected to monitoring and maintenance of order in the wards, providing for the sanitary needs of hospital clients and establishing communication between doctors and patients. Since that time, the role of a nurse in both in-patient and outpatient settings changed dramatically.

The progression of theoretical findings of Nightingale, Orem, Neuman, and other honored nurses established the academic basis for nursing activity (2. Johansen & O’Brien, 2016). Along with it came the sophistication of the profession and standards of conduct that revealed the increased capacity for making educated decisions as a support for physicians’ activities.

Furthermore, scholars and practitioners recognized the importance of nurses as decision makers. Their pivotal role in diagnosis and treatment fostered the development of theoretical models that could enhance their capacity for delivering high-quality service to patients (2. Johansen & O’Brien, 2016). There emerged a variety of individual decision making theories the merit of which seems to revolve around its practicality and simplicity that allows nurses to streamline the process of decision making. One of the more recent models is clinical decision making model developed by O’Neil (1. Banning, 2008). He and his colleagues based this model on the research conducted on graduate students in nursing schools across the U.S. in the late 1990s – 2000s.

As the decision making became a more and more topical issue among scholars, there arose the question of assessment of previous work and proposition of the most effective model (2. Johansen & O’Brien, 2016). The debate about this issue gave rise to the categorization of existing models, and there emerged normative, descriptive, and prescriptive categories of frameworks. Descriptive ones detail the process of decision making as is, without an attempt to enhance it (7. Shaban, 2015).

Such was Simon’s decision making model that consisted of three integral parts such as intelligence, design, and choice. Normative models attempted to envision and foster the pattern under which the ideal decision could be made. Lastly, prescriptive modes documented the methods of producing decisions that could be implemented in real-life situations without exaggerated emphasis on the perfect conditions. The normative models focus on what should be done and how professionals should operate daily, which provides the ground to assume that such theories push nurses towards excellence in patient service (7. Shaban, 2015). The drawback is that they do not account for real situation and cannot be implemented anywhere because ideal situations are rarely present in hospitals.

O’Neil’s Clinical Decision Making

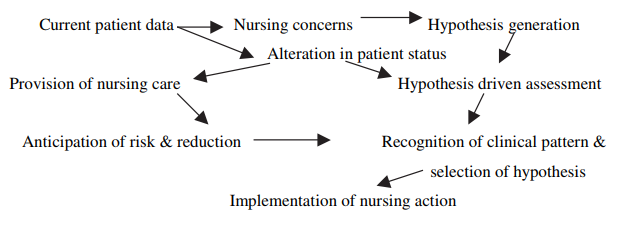

The core assumption under the prescriptive theories is that every decision-maker can make errors and human thought processing could be biased. In light of this, the key proposition was to assume the development of a proper theory that was based on enhancing field experiences of nurses engaged in decision making. With that consideration in mind, O’Neil proposed his theory of clinical decision making the foundational premise of which was the recurrent process of assessment of evaluation of patient’s condition in real time and constant mental processing of the incoming information. There are several key components of the model that could be seen in figure 1.

As seen from the figure, the cycle of data consideration and acting upon assessment is a continuous process. Among the pillars of the model that adds value to its status as a prominent model in the clinical setting is the fact that computer assistance is used in guiding decisions made by a human nurse. The electronic health records and other tools that simplify the access to information about the patient and produce new flows of data are both employed to enhance the baseline, real-time, and post-intervention knowledge to ensure the decisions delivered are top quality (6. Musen, Middleton, & Greenes, 2014).

Another merit of the model is the ranking of risks and conditions, which, according to specialists, contributes to the development of risk-aversive behaviors (1. Banning, 2008). Another advantage is that the model considers using standard nursing action protocols that both ensures the compliance of nurses with practical guidelines and increases the usability of the protocol in actual hospitals.

Hypothesizing is another vital aspect of the model that provides nurses with the opportunity to make educated guesses based on the information gathered through the means of information technology (1. Banning, 2008). One of the most significant strengths of this method is the time economy, which in certain settings such as ICU could be a critical factor (9. Staveski et al., 2014). In addition to that, the model also considers professional and social context by having the nurse assess a variety of factors.

This model also has certain drawbacks, among which scientists find the limited scientific basis. Thus, O’Neil and his colleagues notice that the small scale of the research could undermine the potency of the method in certain clinical settings as the sample did not allow for extensive generalization of the results. In addition, the framework seems to over-reliant on the nurse persona while demonstrating complete neutrality in terms of other participants of the treatment process such as family or colleagues, or physicians. The neglecting of the mediating role of all personnel in decision making is one of the critical negative factors that do not allow to call the model the best available.

Group Decision Making

The latter and the fact that the model gives little consideration to the external factors (labor laws, workload, administration) and internal dynamics in the unit, group models of decision making were proposed. Indeed the acquisition of a certain idea such as collective decision making contributes to de-biasing the process of making quality decisions. Emphasis on the team effort in care delivery is also a recent invention as multi-professional teams rarely included nurses before (2. Burkett, 2016).

Yet, with the advancement of a nurses’ role, the necessity of collective decision making patters emerged. By type, the model appears to be prescriptive as well as it accounts for the biased nature of human decision making (2. Burkett, 2016). In a sense, it is developed to address the critical failures of the individual models such as the confirmation bias, over-reliance on individual decisions and absence of referencing.

Among the critical positive features of the framework is the ability of a group to make decisions that are based on a wider coverage of possible theories (7. Shaban, 2015). If a single individual may only account for a limited number of considerations and is prone to missing critical details, a team of several professionals is more reliable in considering all possible factors influencing the patients’ conditions (7. Shaban, 2015).

Another mediating factor of group decision making model is the fact that participation in the process results in more satisfaction from the result. Indeed the collective effort seems to be eliciting an increased positive response from nurses as compared to decisions made individually (8. Sharma et al., 2016). The possible implications are that choices made as a part of a group are perceived as more meaningful due to the subjective perception of decision weight.

Notwithstanding, the model also has certain drawbacks. One of the most significant is the neglect of personal input, which undermines the proneness of certain individuals to contribute to the process of decision making (7. Shaban, 2015). Poor control for the mechanisms of reward as well as the decreased sense of one’s impact could indeed influence the perceived and actual quality effect from group decision making. In group decision making, it is also difficult to find an individual responsible for concrete contributions which, to a certain extent, hinders the potential for the measurement and assessment of decisions (2. Burkett, 2016).

Model Comparison

Sufficient attention was also paid to a comparison of the models. Thus, scientists discern that it is the setting that influences the adoption and most effective use of one or another decision making paradigm. Thus, in ICUs where the decisions are often made collectively, a team effort is emphasized which predicts the leaning towards group decision making. O’Neil’s model, however, performed better in teaching students the practical basics of the profession.

Interns who adopted this model of decision making reported better confidence in the choices they made, which was also supported by the positive patient outcomes. While there is certain evidence in favor of both models as prominent tools for choice making, there seems to be no evidence on their stable performance across all possible settings. This finding suggests that the diversity of hospital experiences and scope of nursing practice does not allow for universal solutions and encourages the use of tailored approaches.

To this fact also speaks the variety of existing models, each of which was developed by professionals with different backgrounds and practical skills. Thus there is no definitive answer to the question of where or not individual decision making paradigms can outperform individual ones. Certain strong evidence suggests that collective decision making and participation of multiple professionals with a diverse background in the process of treatment is positively associated with the quality of patient outcomes (Shaban, 2015; Sharma et al., 2016).

Yet, it does not directly disprove the fallacy of O’Neil’s approach to making decisions as it was not tested against it in the intern education setting. Indirectly, however, team interactions were reported to elicit positive responses among new nurses who developed confidence in their decisions and elicited lower levels of stress working in a team of professionals (3. Gaesawahong, 2015). On the other hand, nurses that had to start practicing with no group support were prone to more errors and elevated perceived pressure levels (8. Sharma et al., 2016).

One may assume that the biaseness of the results may violate the reliability of such assumptions because measurement of decision confidence, as well as quality and patient outcomes, is related to the collective effort of a team as a whole. Thus, the differences in methodological procedures may indeed undermine the confidence in the comparison results. Yet, if one assumes patient outcomes as the core indicator of the strength of decision making approach, then the bias towards effort recognition could be avoided.

Research shows that the performance of teams in relation to satisfying the needs of patients and increasing their health indicators was better than in single-professional settings. While such evidence might strongly contribute to the team-based approach to decision making as a better and more effective one, there is also a discrepancy in such method (8. Sharma et al., 2016). Kennedy et al. (2015) suggest that the effectiveness of team effort does not fully account for 100% of the influence on health outcomes in patients.

Decision making model may constitute only a small fraction of the influence and other factors such as level of expertize, time allocated to patient care, equipment used, base conditions, and other elements of treatment process may have also interfered with the measurement. Therefore, it appears that no definitive conclusion can yet be reached on the superior effectiveness of either decision making paradigm.

Results and Conclusion

The literature review revealed that decision making is a complex and multifaceted issue which is still topical and debated. The changing nature of the role of a nurse in the 21st century promoted the emergence of multiple frameworks that inform, idealize or describe their decision making (7. Shaban, 2015). Thus, one of the most usable types of decision making frameworks is prescriptive as it allows for a fact of erroneous nature of the human cognitive process and therefore more closely reflects the hospitals’ reality.

The research data on using O’Neil’s clinical decision making paradigm seems to be limited (1. Banning, 2008). While it was indeed based on clinical data, the settings in which it was tested remains limited, which undermines its positions as core decision making practice beyond educative purposes.

In contrast, a group decision making model was supported by stronger evidence that suggests significant positive effects on the patient outcomes. The limitation on the existing evidence is that it to a certain extent, fails to accurately measure the degree of influence of decision making paradigm rather than team effort in general (6. Musen et al., 2014). Thus, the question of separating team dynamics from decision making and measuring it against clinical decision making paradigm remains to be answered. What is more, it appears that the adoption of a concrete paradigm is heavily influenced by the setting and purpose of the unit.

Thus, in team-oriented ICUs, the usage of group decision making was more prevalent while in out-patient settings, clinical decision making was preferred (9. Staveski et al., 2014). These finding also suggest that further comparative analysis need to be produced in order to uncover more definitive information on whether or not group decision making is more effective than clinical decision making tool.

The implications of the findings for nursing practice include the careful consideration of the settings in which one chooses to practice before settling with a particular decision making paradigm. Yet, the knowledge of both would significantly boost one’s employment opportunities as professional versatility increases. Another key takeaway is that the elimination of one’s bias, and the value of the availability of colleagues expertize can greatly decrease the chance of misconduct, which emphasizes the role of team effort in nursing practice.

The application of the results to the current nursing practice is possible in the form of raised awareness of the strengths and limitations of personal choice of decision making framework and the value of fluidity in making sense of patient data. All in all, O’Neil’s and group paradigms of decision making are critical for the nursing profession and present a vast field for further comparative analysis.

References

- Banning, M. (2008). A review of clinical decision making: Models and current research. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17(2), 187-195.

- Burkett, L. (2016). Collaborative decision making: Empowering nurse leaders. Nursing Management, 47(9), 7-10.

- Gaesawahong, R. (2015). A review of nurses’ turnover rate: Does increased income solve the problem of nurses leaving regular jobs. The Bangkok Medical Journal, 9. Web.

- Johansen, M. L., & O’Brien, J. L. (2016). Decision making in nursing practice: A concept analysis. Nursing Forum, 51(1), 40-48.

- Kennedy, C., O’Reilly, P., Fealy, G., Casey, M., Brady, A.-M., McNamara, M., … Hegarty, J. (2015). Comparative analysis of nursing and midwifery regulatory and professional bodies’ scope of practice and associated decision making frameworks: A discussion paper. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(8), 1797-1811.

- Musen, M. A., Middleton, B., & Greenes, R. A. (2014). Clinical decision-support systems. In E. H. Shortliffe & J. J. Cimino (Eds.), Biomedical informatics: Computer applications in health care and biomedicine (pp. 643–674). New York, NY: Springler.

- Shaban, R. (2015). Theories of clinical judgment and decision-making: A review of the theoretical literature. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine, 3(1), 1-12.

- Sharma, V., Stranieri, A., Burstein, F., Warren, J., Daly, S., Patterson, L., … Wolff, A. (2016). Group decision making in health care: A case study of multidisciplinary meetings. Journal of Decision Systems, 25(1), 476-485.

- Staveski, S. L., Lincoln, P. A., Fineman, L. D., Asaro, L. A., Wypij, D., & Curley, M. A. Q. (2014). Nurse decision making regarding the use of analgesics and sedatives in the pediatric cardiac ICU. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 15(8), 691-702.

- Tiffen, J., Corbridge, S. J., & Slimmer, L. (2014). Enhancing clinical decision making: Development of a contiguous definition and conceptual framework. Journal of Professional Nursing, 30(5), 399-405.