Practice Issue

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, bipolar disorder mostly occurs in adulthood; however, children can be affected, too (“Bipolar disorder,” 2016). The disorder was previously known as manic-depressive illness; it is characterized by shifts in mood and emotional condition: people with bipolar disorder experience elated energized states during some periods and experience depressive and anxious states during other periods. It is assessed that the lifetime prevalence of all the types of the disorder combined amounts to two to four percent of the general population (Suttajit, Srisurapanont, Maneeton, & Maneeton, 2014). The disorder is not fully understood from the perspectives of etiology and pathophysiology, and treatment strategies and approaches vary in a wide range; however, an important part of treatment in many cases is the administration of medication aimed at improving patients’ psychological condition during depressive episodes. It is important because suicidal thoughts, along with lowered activity levels, memory and concentration problems, and insomnia, are among typical signs of a depressive episode in people with bipolar disorder.

Medication-related aspects of treating bipolar disorder are rather complicated because it may take years for a patient to find the combination of medications that will address the symptoms effectively in the patient’s individual case (Geddes & Miklowitz, 2013). Types of medications normally used in treatment include antidepressants, atypical antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers (Correll, Detraux, De Lepeleire, & De Hert, 2015). Atypical antipsychotics have been extensively used to treat psychiatric conditions; particularly, quetiapine was initially introduced in the context of searching for effective medications for schizophrenia (Suttajit et al., 2014). However, various studies had stressed the need to estimate the effects of this medication—used either as monotherapy or in combination with other medications—on people with bipolar disorder. Later, it was confirmed that quetiapine can be effective, and it was recommended as part of treating bipolar depressive conditions; however, not all the populations have been examined in this context. Specifically, the effect of reducing bipolar symptoms among children and adolescents has not been sufficiently analyzed. Although it has been observed that the medication can be effective for this population, and there is a low rate of adverse consequences, some authors, including Masi et al. (2015), claimed that the current knowledge about the risks associated with the use of quetiapine among children and adolescents, such as weight gain, is rather poor.

PICOT Question and Components

The PICOT question is formulated as follows: In children and adolescents aged 6-18, does the atypical pharmacological treatment with the use of quetiapine reduce bipolar 1 symptoms compared to the results of standardized pharmacological treatment, such as lithium or combination therapy, within 12 months? The specific PICOT components are presented below.

Population (P): Children and adolescents aged 6-18.

Intervention (I): Atypical pharmacological treatment of quetiapine monotherapy.

Comparison (C): Standard pharmacological treatment, such as lithium or combination therapies.

Outcome (O): Reduce bipolar 1 symptoms.

Timeframe (T): Within 12 months.

It should be noted that the type of bipolar disorder considered in the outcome component—bipolar 1—is characterized by explicit manic episodes that last for more than seven days or by symptoms associated with manic conditions that require professional care (“Bipolar disorder,” 2016). In patients with bipolar 1, depressive symptoms occur, too, and normally last for more than fourteen days.

Description of the Search

In the process of searching for relevant academic literature, keywords were used. In the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) database, the following combination was inputted in the search bar: “quetiapine” AND “children” AND “bipolar.” The use of quotation marks allowed ensuring that those articles will be found in which the exact forms of the three words are used. The use of the capitalized conjunction AND allowed ensuring that the articles displayed among search results will contain all three keywords. Initially, 13 articles were found; however, there was also the requirement to use recent sources (published within the last five years), which is why a limiter was used to display only those articles that were published during the indicated period. When the limiter was clicked, only four articles remained in the search results.

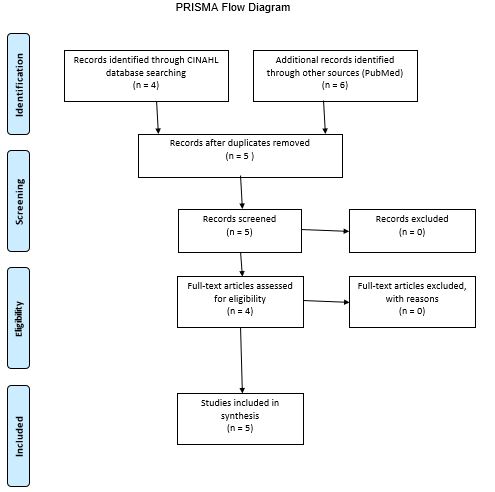

A similar process was adopted for the search process on the PubMed database website: same keywords and the five years publication date. A difference was that, for the PubMed database, it was also necessary to apply the limiter that allowed only those articles the full text of which was available for free. The further process of selecting materials from both databases is structurally presented in a PRISMA diagram (see Appendix A). A particularly important stage was the selection of articles that can be used to address the issue of interest (see PICOT Question and Components). First of all, some articles could be ruled out after reading the title; however, it was necessary for some of the found articles to read abstracts or take a look at certain sections in the body to identify information that can be used in addressing the PICOT question. When the selection process was completed, the selected articles were analyzed, and the result of the analysis is presented in an evidence review table (see Appendix B).

References

Bipolar disorder. (2016). Web.

Correll, C. U., Detraux, J., De Lepeleire, J., & De Hert, M. (2015). Effects of antipsychotics, antidepressants and mood stabilizers on risk for physical diseases in people with schizophrenia, depression and bipolar disorder. World Psychiatry, 14(2), 119-136.

Findling, R. L., Pathak, S., Earley, W. R., Liu, S., & DelBello, M. P. (2014). Efficacy and safety of extended-release quetiapine fumarate in youth with bipolar depression: An 8 week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 24(6), 325-335.

Geddes, J. R., & Miklowitz, D. J. (2013). Treatment of bipolar disorder. The Lancet, 381(9878), 1672-1682.

Habibi, N., Dodangi, N., & Nazeri, A. (2017). Comparison of the effect of lithium plus quetiapine with lithium plus risperidone in children and adolescents with bipolar I disorder: A randomized clinical trial. Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 31(1), 90-95.

Maneeton, B., Putthisri, S., Maneeton, N., Woottiluk, P., Suttajit, S., Charnsil, C., & Srisurapanont, M. (2017). Quetiapine monotherapy versus placebo in the treatment of children and adolescents with bipolar depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 13(1), 1023-1032.

Masi, G., Milone, A., Veltri, S., Iuliano, R., Pfanner, C., & Pisano, S. (2015). Use of quetiapine in children and adolescents. Pediatric Drugs, 17(2), 125-140.

Masi, G., Pisano, S., Pfanner, C., Milone, A., & Manfredi, A. (2013). Quetiapine monotherapy in adolescents with bipolar disorder comorbid with conduct disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 23(8), 568-571.

Suttajit, S., Srisurapanont, M., Maneeton, N., & Maneeton, B. (2014). Quetiapine for acute bipolar depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Design, Development and Therapy, 8(1), 827-838.

Appendix A