Abstract

With an average annual growth rate of 11.1 percent from 1970 until 2006, the pharma market is one of the fastest-growing markets in the world, reaching more than US$400 billion in sales in 2003 (PhRMA, 2004). The industry is now going through a major consolidation stage where direct product innovation strongly relies on existing products. Two categories of innovation lead to organic revenue: incremental innovations in the form of drug enhancements (such as drug adherence, medication combination, etc.) and radical innovations in the form of new drugs. This paper will focus on incremental innovations and drug adherence in particular. While drug adherence is a long-term concern of the pharmaceutical industry, I attempt to the hypothesis that strategic alliances formed by firms not only lead to increased drug compliance rates but also in a long run, lead to improved overall national health.

Introduction

Success in the pharmaceutical industry depends on a leadership centered on the following management practices (Needleman, 2001): (1) selecting excellent targets for drug discovery, (2) focusing limited resources to enhance speed, (3) breaking down barriers amongst R&D activities, and (4) managing product lifecycles effectively.

The returns can, of course, be immense when a pharmaceutical company is first to market with a patented, breakthrough drug. One need recall only the example of Pfizer’s Viagra or the biggest American and European combines currently racing to develop a vaccine for Type AH1N1 influenza (‘swine flu’). It stands to reason, therefore, that the major US and European pharmaceutical companies invested more than $40 billion in R&D in 2003. However, the odds are long. R&D processes can last up to 13 years, only one of 5,000 product-ideas is approved for commercial sale (Pelz, 1976), and only one out of 10,000 substances becomes a marketable product (Volker, 2001).

This paper will mainly focus on managing the product life cycle and discuss the institutional forces within the pharmaceutical industry for delivering better care and incremental growth. These two factors are related because patients stand a better chance of attaining a complete cure if they comply fully with a prescribed drug regimen. And from the pharmaceutical company’s point of view, a higher incidence of adherence sustains unit volume throughout all stages of the product life cycle.

Adherence to (or compliance with) a medication regimen is generally defined as the extent to which patients take medications as prescribed by their health care providers. The word “adherence” is preferred by many health care providers, because “compliance” suggests that the patient is passively following the doctor’s orders and that the treatment plan is not based on a therapeutic alliance or contract established between patients and physicians. In business terms, adherence to a course of treatment has favorable effects on incremental organic revenue, strategic long-term revenue, and cost synergies.

Adherence interventions have been developed recently that target ambivalence toward medication through behavioral strategies. But such interventions are not in widespread use in standard practice. From the national health point of view, the non-adherence to drug therapy causes 6 percent to 10 percent of all hospital admissions and costs $50 billion annually in avoidable healthcare costs, according to a national health statistics WellMed (2001). “US patients who fail to take their medications as prescribed represent a staggering economic and social cost” (PharmacoEconomics; 2006, p15). Thus, non-adherence to medications is associated with high rates of relapse and re-hospitalization.

There is a dearth of prior literature revolving on strategic analysis of drug adherence. Therefore, the need exists to analyze causes of non-adherence as a key influence on revenue fluctuations in firms, whether or not they form strategic alliances and at any stage before or subsequent to forging alliances. By forming strategic alliances, firms can potentially access social, technical, and commercial resources that normally require years of operating experience to acquire.

Effective alliances provide access to more diverse information and capabilities. Market access is a key capability when it comes to drug marketing and direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising. Hence, access is a critical commercial asset that firms may obtain via alliance. Thus, this research will emphasize the main causes of the non-adherence in view of all aspects affecting revenue.

This paper will proceed in the following manner. First, the relevant literature on drug adherence and strategic alliances will be reviewed. Then, arguments will be presented to advance the presented hypotheses, and the methodology to empirically test the hypotheses will be conveyed. The fourth section will report on the results of the meta-analysis and econometric analyses. The last section will discuss the theoretical and applied implications of this study, as well as highlight limitations and avenues of future research.

Literature review

Overview from a Marketing and Customer Perspective

As pointed out below in section IV-A. “Study Variables and Measures of Adherence”, there is any number of external and modifying influences that impinge on drug adherence. Notwithstanding the fact that the product under study, Lipitor (atorvastatin calcium), is meant to prolong the life expectancy of patients with frank hyperlipidemia, there is any number of substitute products. Lipitor may be the single best-selling brand in the industry and, at last, count, boasted a 42% market share in the cholesterol-lowering product class. But that is more a tribute to the marketing prowess of Pfizer than to breakthrough R & D (Simons, 2003). After all, statins (as the therapeutic class is termed) were first approved by the FDA for commercialization a full ten years before Lipitor went to market. The first statin, mevastatin, was identified in the early 1970s. Clearly, physicians have a choice. So does the highly educated ‘baby boomer’ generation, now in middle age or close to retirement and now paying the price for a carefree lifestyle and eating habits.

Furthermore, many researchers have proposed a service and customer relationship management (CRM) view of the physician-patient relationship (see, for example, Lim and Varkey, 2005). This is particularly true of chronic disorders like hyperlipidemia, for which lifetime management and care is the norm.

Hence, this study proposes to employ the frameworks of self-determination and customer relationship management from mainstream marketing to better understand the dynamics of drug adherence.

Self-determination theory recently drew attention because of the disappointing and even contradictory outcomes of promotions in service marketing. The a priori impact ought to have been direct and positive since consumer marketing has long believed that service factors (e.g. reminders via email and other channels) and economic bonuses (price offs, premiums) should trigger customer loyalty if competitive activities, pricing, and retaliation are held constant.

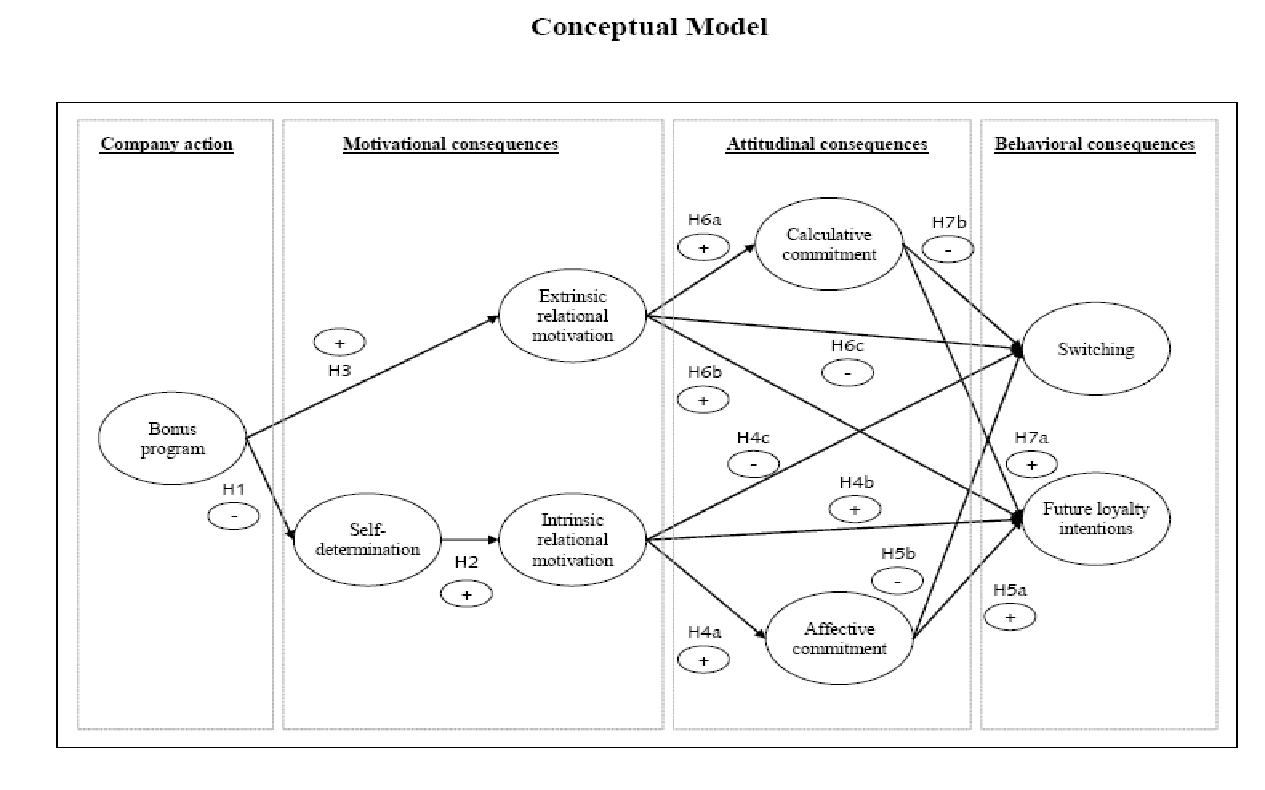

Very recently, however, Dholakia (2006) fell back on self-determination theory to explain contradictory outcomes of longitudinal studies on customer loyalty. It was his contention that self-determination operated on consumers to make them perceive that promotions and other ‘extraneous factors were ‘too controlling’ and therefore deserved to be resisted. Since that bit of insight offered no proof in point of quantified changes in customers’ self-determination after exposure to extrinsic factors and was not rigorous enough to account for alternative explanations related to customer self-selection and brand loyalty, Hennig-Thurau and Paul (2006) manipulated the independent variable in a laboratory setting. The outcome was a more complete model-based firmly on self-determination theory (see Figure 1 overleaf) and suggesting the operation of intervening variables such as motivational and attitudinal consequences.

Thence, the research team drew the implication that incentives like an economic bonus program reduce intrinsic relational motivation because of the adverse effect on self-determination. In turn, this degrades future loyalty intentions and increases switching rates. By raising consumer extrinsic relational motivation and calculative commitment, secondly, incentive programs have the same effect on loyalty and switching.

The second framework proposed is that of service marketing. This is a reminder that the physician-patient transaction is less a commercial transaction than a package of benefits that the patient purchases. The ultimate effect of interest is a physical count of pills (and other dose types) but it is also a proxy for altruistic good sense and loyalty to the service offered by the physician.

As a product class, statins have achieved rapid penetration and may therefore be already in the early maturity stage of the product life cycle. Since statins have comparable effects (generics are already available) and, in consumer terms, impose little by way of switching costs beyond relative price, marketing theory suggests that service quality becomes the paramount influential variable on customer loyalty.

In mainstream consumer goods, the literature is replete with repeated confirmation of the relationship between achieving high service quality, on one hand, and the entire spectrum of business performance variables: loyalty, word-of-mouth endorsement, customer satisfaction, price-inelastic behavior, volume turnover, and market share accomplishment.

There is a great body of customer relationship management tools to optimize the patient-health service provider. Over time, the relationship proves to be dynamic, a “moving target.” First of all, consumer wants to evolve. This is partly due to the fact that patients grow more ‘expert’ in respect of the clinic or primary care unit they repeatedly transact with and the market context as well. With greater familiarity comes rising norms of service and greater awareness about therapeutic alternatives.

Thirdly, the relationship between patient and physician-centered service organization grows in scope and complexity (Reimartz and Kumar, 2003). Confidence in the efficacy of care expands. Referrals result in relatives and friends ‘buying into’ the service, too. Familiarity with the patient then helps the primary care unit offer ancillary, revenue-producing services such as reminder services or metered dispensers. With a greater flow of benefits comes enhanced loyalty to the clinic and, presumably, the statin brand prescribed. In short, there are no more barriers to switching from the service and its associated therapeutics (Jones, Mothersbaugh and Beatty, 2002).

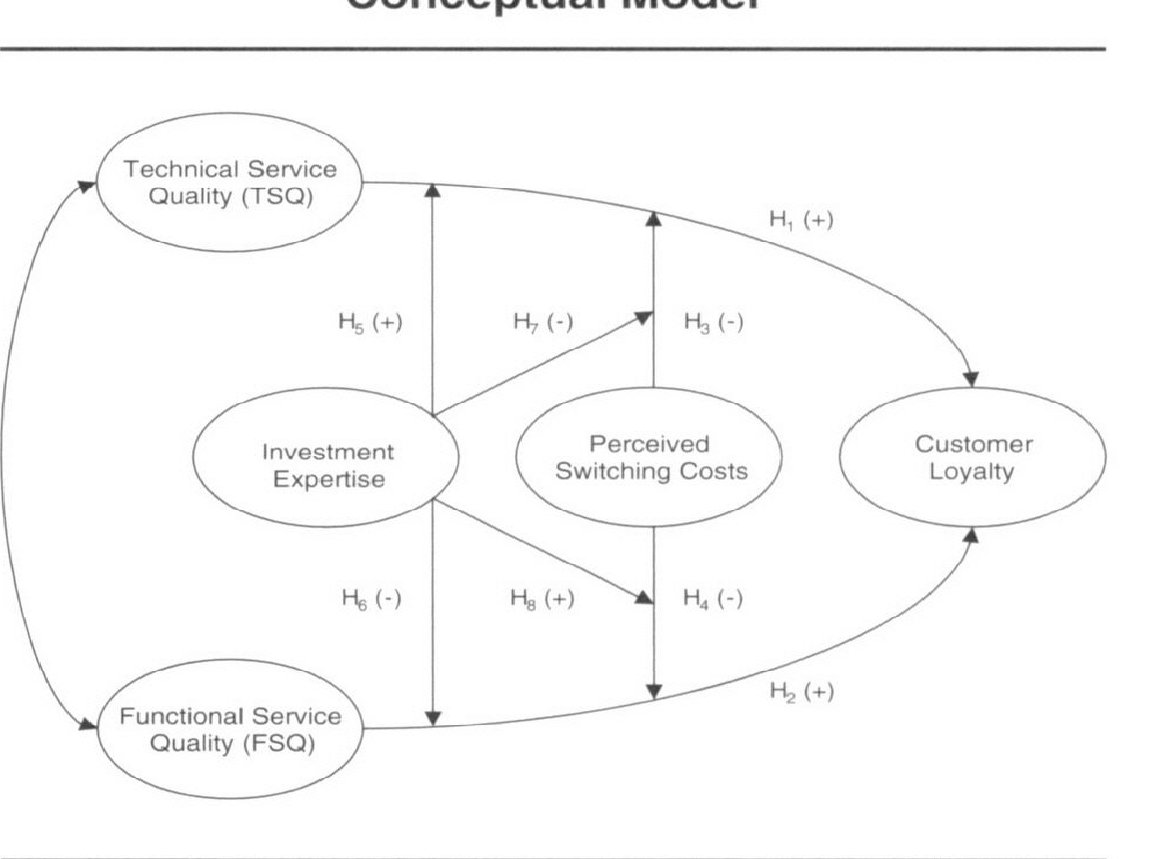

Accordingly, Bell, Auh, and Smalley (2005) conceptualized the model in Figure 2 below that posits a change in perceptions of service quality with growing patient sophistication and the number of switching barriers. More important, this theoretical model assumes that service can be disaggregated into technical and functional quality components; both, in any case, impact patient loyalty to physicians and brands.

Subsequently, this model was cited by, amongst others: Chiu and Chang (2006); Yan (2007); Yoo, Choi, Kim, Yang, and Jong (2009); Paul, Hennig-Thurau, Gremler, Gwinner, and Wiertz (2009); Dagger, Danaher, and Gibbs (2009); and, Berenguer-Contrí, Ruiz-Molina, and Gil-Saura (2009).

The Medical Viewpoint

No fewer than 2,049 articles on “patient compliance” were published in 2005, twice the number published 10 years earlier. Conditions associated with cardiovascular (CV) health are well-represented in adherence research, accounting for nearly 20% of adherence articles published in 2005.

Combining both the adherence and the innovation adoption literature provides a starting point for understanding how managers can systematically influence the drug compliance process over time. The literature review section will present the following reviews: Overall adherence fundamentals with essential and external causes, financial incentives, and effective lifestyle planning & T-36 as a direct impact to the adherence.

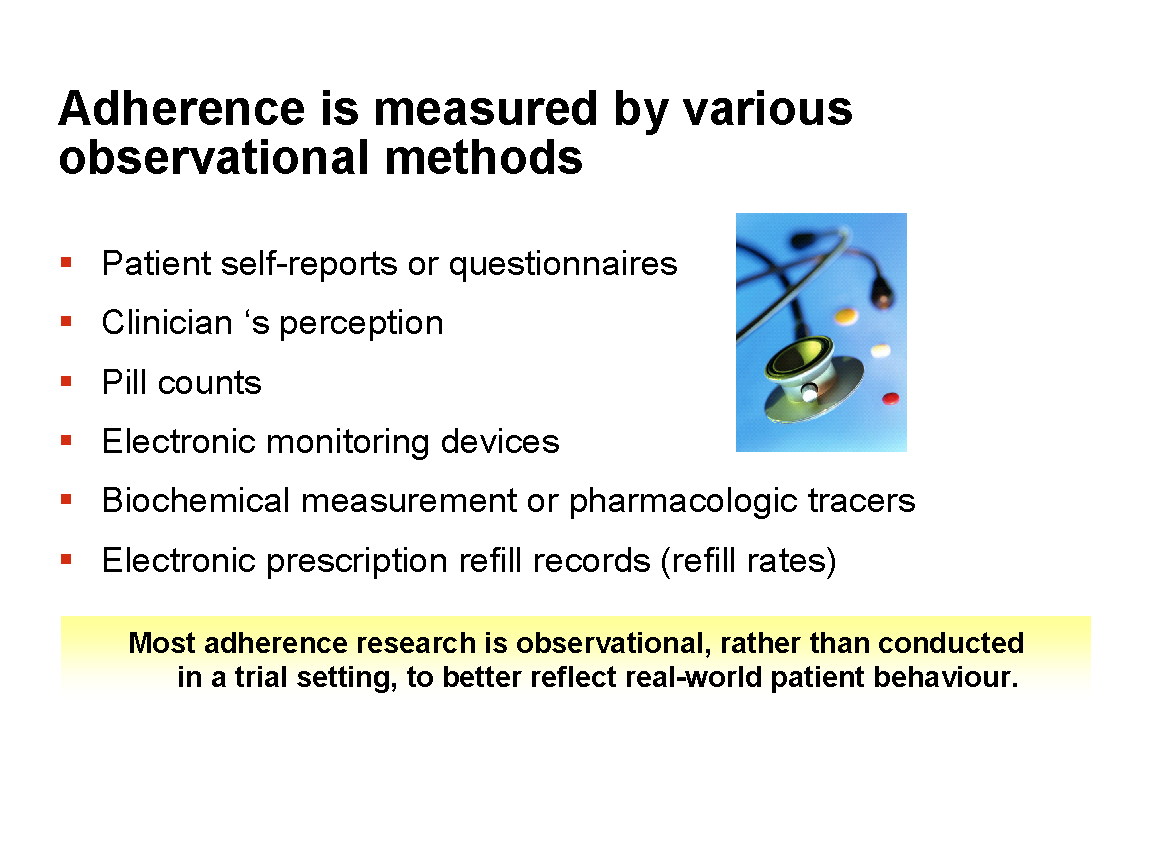

Adherence to medication is measured as a percentage of prescribed doses that were actually taken, over the course of a defined period of time. Doses that were taken/doses that were prescribed x 100 = adherence over an X-day period.

Persistence is the duration of treatment and is measured as the number of days from initiation to discontinuation. Measures of both adherence and persistence are obtained from:

- Patient self-reports or questionnaires;

- Clinician perception;

- Pill counts and liquid levels;

- Electronic monitoring devices;

- Biochemical measurement or pharmacologic tracers;

- Electronic prescription refill records (refill rates);

Few studies have examined drug costs and adherence in similar patient cohorts across countries. The proportion of patients reporting non-adherence because of cost ranged from 3 percent in Japan to 29 percent in the United States. Out-of-pocket spending was related to national pharmaceutical financing policies and predicted national non-adherence rates. However, inconsistencies in the relationship between patient costs and non-adherence suggested that other social or policy factors also matter (Hirth, 2006). A McKinsey study (2001) of people with hypertension revealed that nearly half of those diagnosed with the disease do not adhere to their drug therapies. If medical professionals and pharmaceutical companies better understand patient attitudes, they could save both lives and money. The study classified patients by their attitudes towards medicine in general and compared them to treatment adherence (Hopfield, 2006).

A study by Paez (1996) of pharmacy claims data revealed that enrollees in pre-deductible plans were much more likely than those with other coverage to discontinue medications, thus forcing a re-thinking of the benefits of direct to consumer health plans. Another research by Walker (2005) demonstrated that patients who were prescribed generic or preferred medications by their physicians were the most likely to adhere to their treatments. This study suggested that patients and physicians need to pay close attention to the formulary status of medications when prescribing to improve adherence.

One concedes that reading and interpretation errors also have a bearing on non-adherence. Significantly, Congress passing the law related to Electronic Medical Records coincided with the publication by a group of researchers lead by Dr. Kaufman (2006) of the results of their study demonstrating a significant reduction in medical errors and increased adherence when medications were prescribed electronically and thereby avoiding potential human error.

On dose frequency and dose interval, a study by Hughes (2006) demonstrated the importance of drug frequency administration: whether medicines that require less frequent administration are better than drugs that do require frequent administration. According to the author, drugs that are less frequently administered improve patient adherence, but medical practitioners and patients should focus more on the effectiveness of the drug and not on its cost.

Some studies suggest that many patients discontinue medication prematurely for reasons such as poor response, side effects, stigma, and miscommunication. Patients were also less likely to stop if they were older, married, had public or private insurance, or had made eight or more visits to a nonmedical therapist (Hodgkin, 2007). Thus far, the literature review has demonstrated the multifactorial nature of non-compliance with a course of medication.

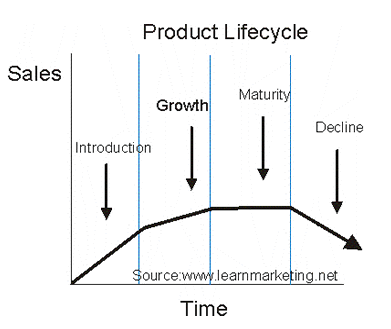

Effective Drug Life Cycle Planning and T-36

Consideration of where a formulation or drug brand is in the product life cycle (PLC) also influences the strategic relationship between drug adherence and product turnover in the medium or long term. PLC bears on the overall analysis of this study because the four major phases of the cycle provoke the involvement of many professional disciplines and requires many skills, tools and processes.

Product life cycle has to do with the life of a product in the market with respect to business/commercial costs and sales measures; whereas product life cycle management has more to do with managing descriptions and properties of a product through its development and useful life, mainly from a business/engineering point of view.

This longstanding analogy based on biological lifespan has had its adherents, during the post-World War II period when fast-moving consumer goods were predominant, media choices were narrower and consumers typically did not possess enough information to be very discriminating. More recently, PLC has had more than its fair share of detractors.

To say that a product has a life cycle is to assert four things: 1) that products have a limited life, 2) product sales pass through distinct stages, each posing different challenges, opportunities, and problems to the seller, 3) profits rise and fall at different stages of the product life cycle, and 4) products require different marketing, financial, manufacturing, purchasing, and human resource strategies in each life cycle stage. Box (1983) offered an interesting point of view that compliance is more critical at the introduction and growth stages of PLC rather than later once a brand has started to decline. There are two flaws in this reasoning. First of all, frontloading adherence-boosting product management does not take into account the fact that PLC can be extended again and again. Even if the product life cycle could not be resuscitated because the five-year protection from drug patents has just expired, secondly, drug adherence becomes even more vital at the maturity and decline stages were ‘harvesting’ to maximize profits is the logical product management strategy.

Nonetheless, the lesson is clear. In order for the concepts of adherence and following-up with customers to be effective, they have to be considered at almost every step mentioned above.

Hypotheses

The main objective of this research is to test the following hypotheses:

H1: As pharmaceutical firms form alliances, overall adherence to drugs increases and corporate revenue increases.

Null Hypothesis H1: The strategic alliance between Pfizer and Pharmacia signed in 2002 did not improve drug adherence or unit sales for Lipitor.

Business alliances may create the less confusing corporate structure with directly defined goals and responsibilities. The above hypothesis suggests multiple benefits of forming alliances: decreased operational cost, retention of the highly skilled workforce increased efficacy and effectiveness of completed tasks that can make a direct positive impact on overcoming barriers related to drug adherence and thus increasing corporate revenue.

Next, is review of potential essential and external causes associated with drug adherence:

Adherence Essential Causes: Adherence External Causes:

- Side-effects – Doctors

- Value of Drug – Hospitals

- Regimens – Pharmacy

- Dose – Regulators

- Formulation: IV vs. Tablet – Insurance / Payers – Cost

H2: Drug adherence due to essential cause is greater than drug adherence due to external causes.

The basis for Hypothesis 2 is that essential causes are less subject to change, where relevant objective information regarding drugs is presented in a scientific, statistical, and epidemiological fashion. It is axiomatic, after all, that environmental variables are less easily managed than essential causes. On the other hand, revenues from drug adherence due to the essential causes are less than revenues from drug adherence due to external causes because the latter are exogenous to the pharmaceutical company. Being so, they are the likelier sources of marginal income for the firm.

Methodology

Study Variables and Measures of Adherence

Adherence to medication regimens has been monitored since the time of Hippocrates when the effects of various potions were recorded with notations of whether the patient had taken them or not. Even today, patient self-reports can simply and effectively measure adherence (Dr. Osterberg and Dr. Baschke, 2005).

The use of clinical outcomes, available from retrospective reviews of medical and primary health care records, as an ‘effect’ of drug adherence, is itself confounded by many influential or intervening factors other than adherence to a medication regimen that can account for clinical outcome.

The most common method used to measure adherence, other than patient questioning, has been pill counts (i.e., counting the number of pills that remain in the patient’s medication bottles or vials). Rates of refilling prescriptions are an accurate measure of overall adherence in a closed pharmacy system (e.g., health maintenance organizations, the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care System, or countries with universal drug coverage), provided that the refills are measured at several points in time.

Electronic monitors capable of recording and stamping the time bottles when bottles are opened, dispensing drops (as in the case of glaucoma), or activating a canister (as in the case of asthma) on multiple occasions have also been used for approximately 30 years (Rudd, 1998).

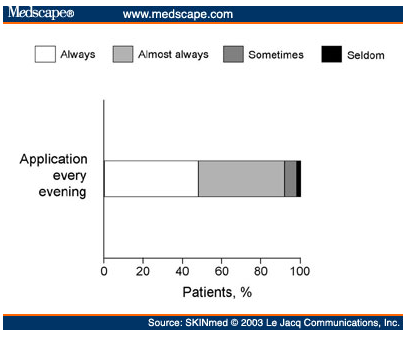

Figure 5 above reflects insights into patients’ behavior in taking medication, but they are still indirect methods of measuring adherence; they do not document whether the patient actually ingested the correct drug or correct dose (Spilker, 2001).

Other indirect measures combine the virtues of behavioral and quasi-observational data-gathering. In assessing the utility of email reminders to improve return rates of outpatients, for instance, Lim and Varkey (2005) at Erlanger Bledsoe and Mayo Clinic, respectively, refer to the widespread use of retrospective culling of clinic records and a plan to test more rigorously using a randomized controlled clinical trial method.

On the other hand, the cost of such direct measurement methods as electronic monitoring is not covered by insurance and thus these devices are not in routine use. However, this approach provides the most accurate and valuable data on adherence in difficult clinical situations, in clinical trials, and adherence research settings and has advanced our knowledge of medication-taking behavior (Urquhart, 2001).

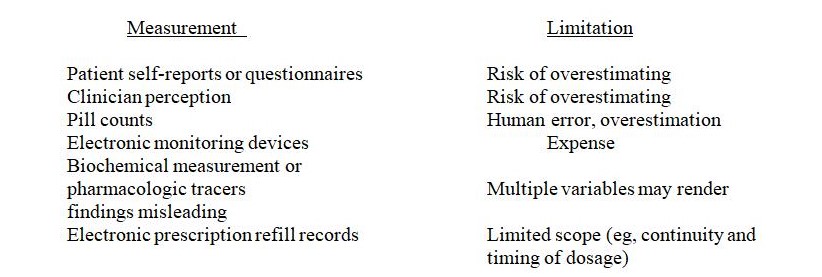

In summary, all above mentioned methods for measuring adherence have limitations:

Table 1: Definitions and Operationalizations of Variables

Dependent variable – drug adherence

Independent variables

Control variables

Confounding Variables

- Patient co-morbidities

- Rx Data:

- Patient Demographics

- Prescriptions (NDC code)

- Quantity Dispensed

- Days Supply

- Health Plan

Data Sources

Given the novelty of this investigation, the study will take a two-track approach. Quantitative rigor will be provided with statistical analysis of healthcare records in the International Medical Specialties (IMS) database. Owing to the exploratory stage of the research into the relationship between strategic alliances and drug adherence outcomes, the second approach will employ a summative meta-analysis.

The main data source that is utilized is IMS – the oldest healthcare informatics organization with a global reach in over 100 countries. The main advantage of IMS is its comprehensive access to healthcare system data: from the pharmaceutical and biotech industry to HMOs, researchers, physicians, government agencies, supply chain providers, financial services sector, etc. From a functional perspective, IMS Health Incorporated provides business intelligence reporting, prescription tracking reporting, and pharmaceutical audits, medical audits, prescription audits, hospital audits, and published audit reports, as well as analysis of anonymized prescription and/or medical records.

IMS data sets also include MIDAS, an online multinational integrated data analysis tool to assess and analyze global pharmaceutical information and trends in multiple markets; other portfolio optimization reports; and promotional audits and promotion management consulting, pricing and market access consulting, oncology analyzer, and consulting, and forecasting portfolio services. Thus, the overall purpose of utilizing IMS sources is to identify key variables related to this research that can lead to the improvement of preventive medicine outcomes for the population in general. In general, secondary research and statistical analysis on IMS data, therefore, paves the way for strategic decisions that can have positive clinical and financial implications.

Sample Selection from the IMS Database

As the US healthcare is moving from acute medical management to preventive medicine to model both clinical and financial outcomes, I have opted to confine my study sample to the following categories:

- Focus on chronic diseases: the reason for doing so is based on Department of Health 2007 statistics stating that 70% of healthcare dollar resources are spent on the management of chronic conditions

- Since medications under the group of “statins” are prescribed to treat chronic conditions, Lipitor was chosen to represent this medications group from clinical efficacy data (American Cardiology Association , 2006)

Proprietary brand data will be evaluated for the purpose of compatible drug formulary analysis.

The following dependent variables are reviewed:

- medication refill rate

- revenue generation

Statistical Analysis

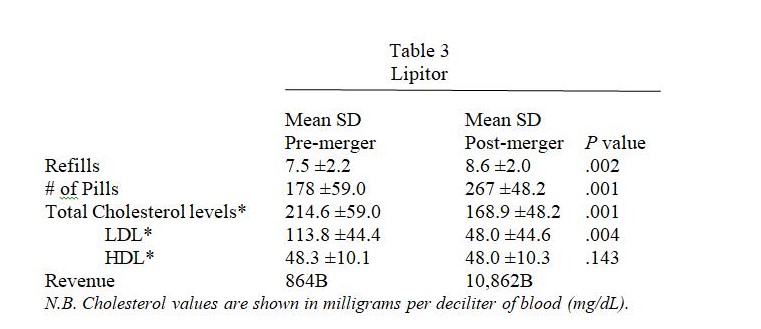

The merger in 2002 between Pfizer and Pharmacia provides the backdrop for a pre-and post-analysis of brand performance in the IMS database. Pfizer – best-known perhaps for its impotence drug Viagra and a listed company the shares of which have been part of the Dow Jones Industrial Average since April 8, 2004 – had by then already acquired another world-beater in the cholesterol-lowering brand Lipitor on buying out Warner-Lambert two years previously.

Pharmacia itself was a comparatively obscure end result of three mergers. Starting life as Searle in 1888, G.D. Searle was acquired by Monsanto nearly a century later. Separately, Upjohn and Pharmacia merged in 1995 to become Pharmacia & Upjohn. The company name was streamlined to Pharmacia when the combine snapped up Monsanto in April 2000, spun off the agricultural chemical operations, and retained G.D. Searle.

The benchmark brand in this analysis, Lipitor (atorvastatin calcium) Cholesterol-Lowering Medication, was synthesized in 1987 by Warner-Lambert and brought to market in 1998 (Simons, 2003, p. 1). Lipitor is a vital criterion in this study because it is not only the number one brand of Pfizer (after the 2000 acquisition of Warner-Lambert) but also the single best-selling drug in the industry globally (Van Arum, 2009, p. 1).

Statistical Analysis was performed using SAS version 9.12. The statistical method for comparison of pre-merger compliance was by two-tailed t-test. Sample size came to a total of 1676 patients of Lipitor pre-merger in 1997 and 5611 customers in 2004. The mean age of both groups was 58.4 years. The overall population was approximately 18.3% male, but males represented 32.8% of the age cohort above 67 years.

Summative Meta-Analysis

This sub-set of statistics acknowledges the sparse nature of precisely relevant literature by seeking to combine findings of even a handful that employed hypotheses comparable to those in the present study. Such utility harks back to the first implementation of the approach by Karl Pearson in 1904, an effort to overcome the limitations of conceptually rich but limited-sample related research. In present-day scholarly research, meta-analysis is frequently deployed in epidemiology and evidence-based medicine but not with any great frequency in market research, management, and organizational theory.

Meta-analysis typically embarks on an exhaustive search of multiple journal databases to extract, first, those that precisely match the current investigation of drug adherence effects from strategic alliances of pharmaceutical companies; if the core results are too sparse, a second set is generated that loosens the relevance criterion to sales or market share gains arising from strategic alliances within any consumer product category characterized by moderate to high repeat usage rates. At whatever level of relevance the canvass of related research operates, what is key is that the meta-analysis finds or converts to a common, quantitative criterion variable that will facilitate combined statistical operations. Otherwise, the best that can be hoped for is to report average effects sizes for comparable market and consumer variables (Glass, McGaw, and Smith, 1981; Hunter and Schmidt, 1990; Higgins and Green, 2008).

The studies shall need to share a common operationalization of a dependent variable (DV) or an effect size similar to drug regimen adherence that is the focus of this present research. Descriptive or summative treatment is the less-rigorous, first stage of meta-analysis. At this level, one calculates for average effects sizes. Should the DV be precisely equal across several studies, modified meta-regression might even be possible in a second, subsequent stage. As in the logistic regression done on the IMS two-sample data, statistical meta-analysis controls for influential or intervening variables, the study characteristics this time.

Findings

Quantitative Analysis

The likelihood of 80% or more persistence with lipid-lowering therapy was estimated from odds ratios calculated through unconditional logistic regression using the SAS procedure. Confidence intervals for the estimated odds ratios and significance tests for differences from the null value were calculated using the estimated standard errors. Potential determinants of persistence in the regression model included age, sex, presence of markers, number of filled prescriptions, etc. Two-tailed p values less than.05 were considered significant. While comparing two groups, the higher compliance was observed in a post-merger group, the lower one was observed in pre – on -pre-merger study group; even after controlling for individual patient characteristics.

Baseline differences between the intervention and control groups with respect to age, sex, statin purchaser, pre-merger, and post-merger were assessed with adjustment of the standard errors for the intercorrelations of matched patients using multiple linear regression models for continuous variables and logistic regression for categorical variables. The unadjusted relationship of the group on the change in statins compliance was assessed using multivariate linear regression with adjustment for the intercorrelations of matched patients. The analysis was performed by removing patients with co-insurances and intervention patients who switched from branded to generic forms of other cholesterol-lowering drug classes.

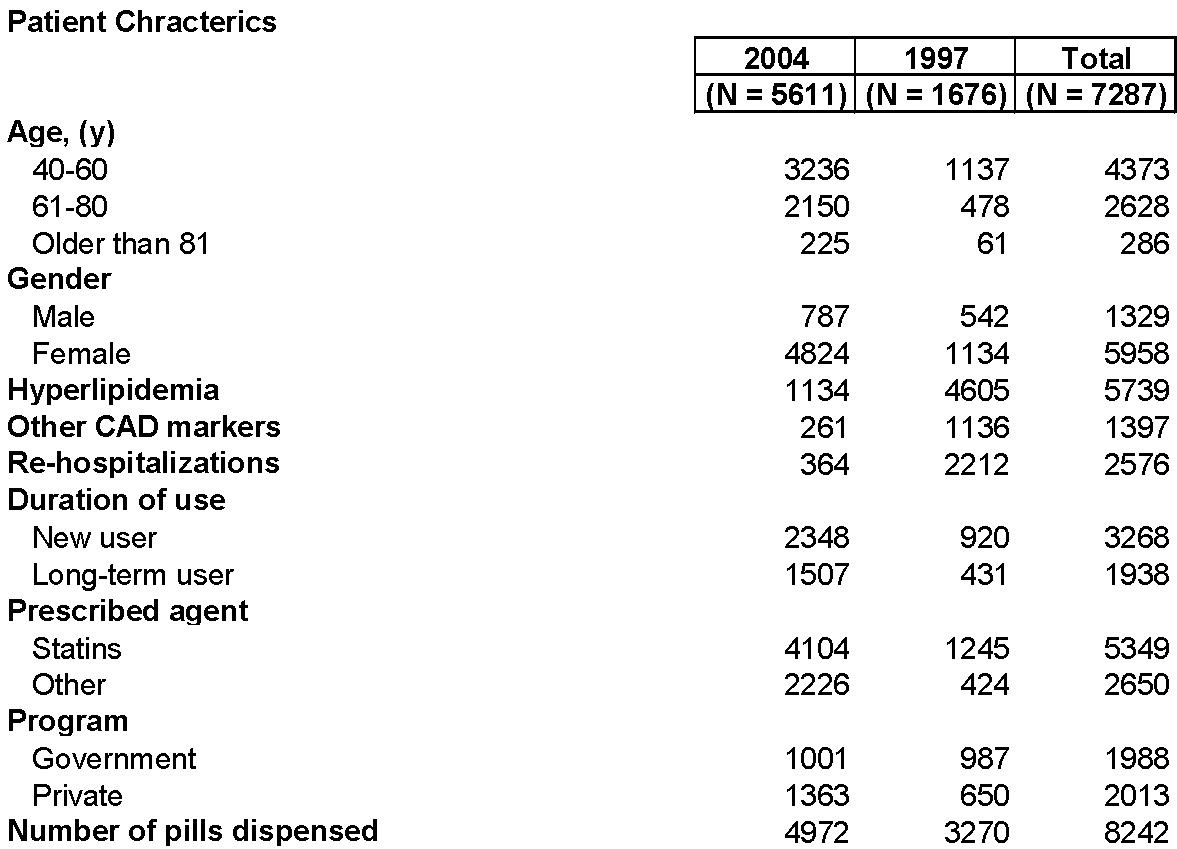

Table 1 presents the demographics of patient characteristics pre and post-merger.

Table 1: Еhe demographics of patient characteristics pre and post-merger

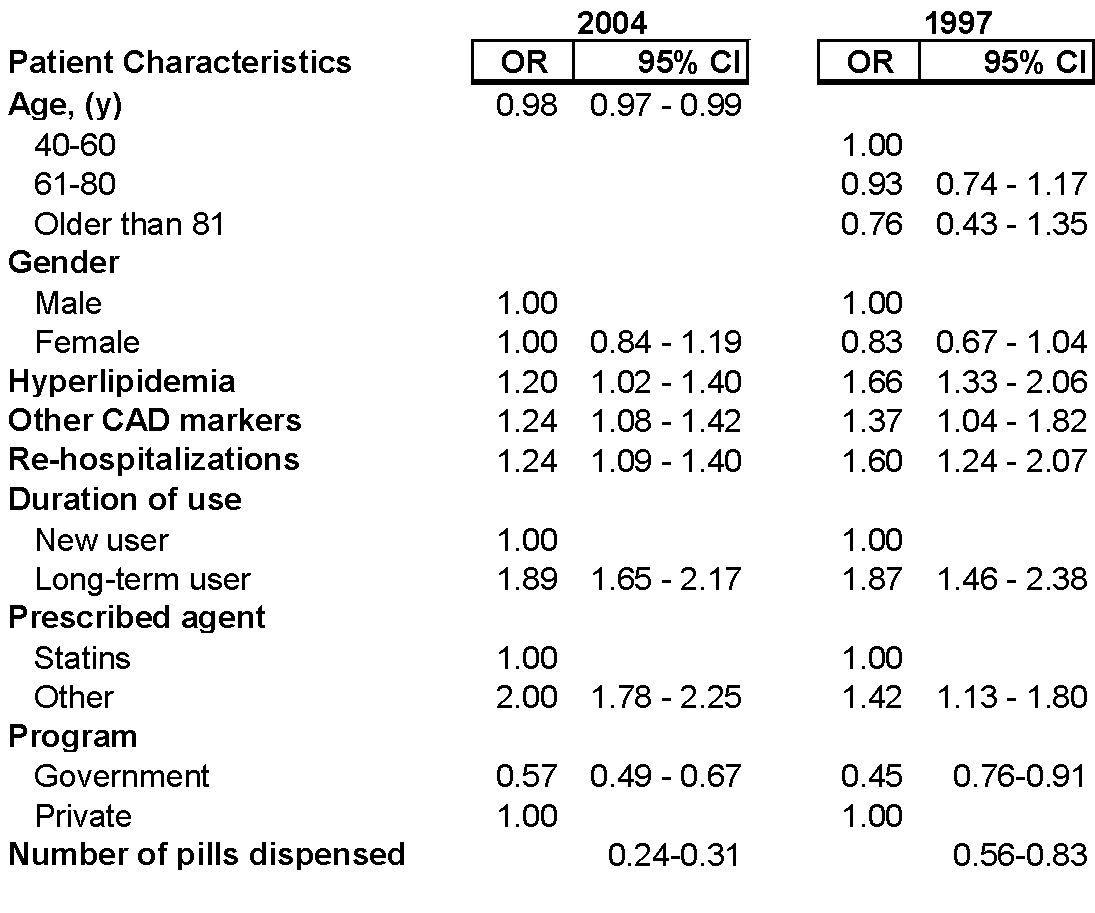

Table 2 below show uneven outcomes. On the positive side of things, female patients evince somewhat the better adherence compared to baseline, as did those who were prescribed some other drug class besides statins to manage elevated cholesterol levels. For some reason, patients seen at public primary care institutions demonstrated better adherence compared to the baseline seven years previously. This leads one to hypothesize on the operation of (unmeasured) socio-economic factors, access to second medical opinion and the like.

Table 2: Relationship Between Patient Characteristic and High Persistence

OR indicates odds ratio; CI is confidence interval; CAD is coronary artery disease

On the other hand, compliance seems to have eroded when the total drug regimen and patient characteristics are analyzed. The total number of pills dispensed apparently dropped over time. As well, adherence declined for patients with coronary artery disease and hyperlipidemia, the latter being precisely the condition for which statins are prescribed. Finally, there is a negative relationship between adherence and the number of confinements. Odds are that poorer average intake of statins over time for those who had been admitted to hospital at least once from 1997 to 2004 reflects nothing much more ominous than being shifted to other drug classes for a stroke or associated, life-threatening conditions such as cardiovascular disease.

Concerning the performance of Lipitor itself from the pre- to post-merger benchmarks, the IMS projections based on retail audits suggest a drastic 92% drop in dollar volume (although one concedes that the dollar values projected from uneven sample sizes are distinctly unreal), notwithstanding the fact that mean number of refills shrank just 13% over the seven-year period whilst tablet consumption fell by a third.

The measurable, long-term consequence of poorer Lipitor performance is that average values for total cholesterol level crossed over to “borderline high” (American Heart Association, 2009) whilst low-density lipoprotein (LDL, commonly termed “bad” cholesterol) was borderline high amongst patients seen for hyperlipidemia.

Meta-Analysis of Relevant Literature

A search of the non-medical literature for common effects measures of the relationship between strategic alliances and drug adherence did not prove fruitful at all. As may be seen for a two-study ‘meta-analysis’ in the subsequent pages, the criterion measures were as diverse as percentile rank for adherence, a ‘linear’ (i.e., ratio-type variable) medication possession ratio, and success in earning regulatory approval operationalized as an enhanced capacity for meeting FDA standards for product quality and patient safety.

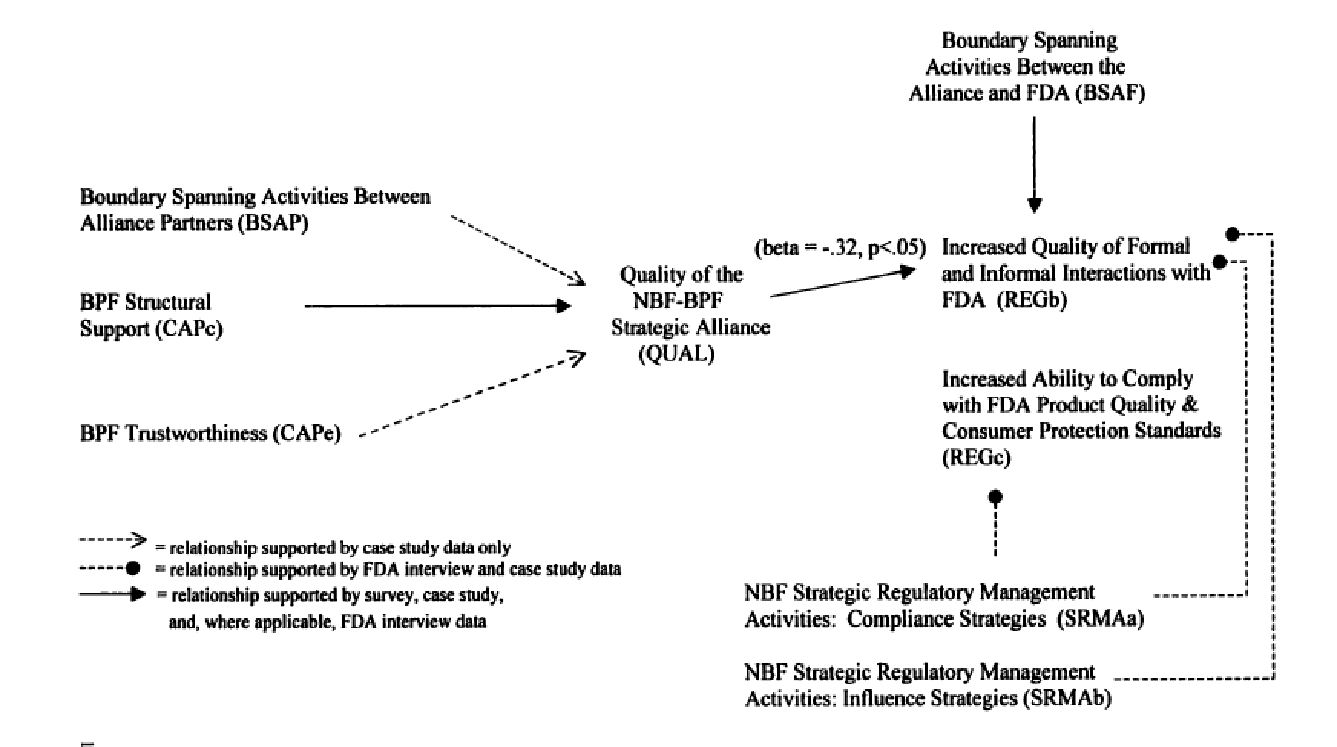

Doshi (2000) explores the utility of strategic alliances in shortening time-to-market, specifically success rates in obtaining approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for commercialization. The author proceeds from the framework of organizational collaboration theory – specifically that bearing on networked instead of merged organizations – and examines the utility of two principal criterion variables: the separate capabilities of each partner and motivation to collaborate. Other variables hypothesized as modifying or contributing to the desired outcome of regulatory approval were: the quality of the alliance, ‘boundary-spanning activities, strategic management of the regulatory process, and quality of both formal and informal interactions.

Data-gathering took the form of measuring the criterion variables on a universe of biotechnology firms that had been in operation long enough to forge alliances. The data was then subjected to multiple regression and factor analysis. As well, insights and diagnostics were derived from exploratory qualitative research that took the form of case studies and depth interviews with regulatory officials.

Ultimately, Doshi finds that three organizational variables were more important in attaining the intermediate outcome of higher quality collaboration. These are ‘boundary-spanning activities, structural support, and level of mutual trust (see the model in Figure 6 overleaf). Another intermediate and critical result, better quality of formal and informal interaction with the FDA, was in turn positively associated with boundary-spanning activities between the FDA and the partners acting in concert. And strategic management of regulatory compliance was strongly linked with success in complying with product quality and safety standards of the FDA.

Nowhere in the body of theory assessed nor in the exploratory research leading up to main model-building task does the author uncover the possibility of linking the fact of a strategic alliance to drug adherence or proxies such as unit growth and market share.

Focusing on patient-intrinsic variables, Yoon (2008) investigates hypertension patients directly but limits the ambit of the analysis to consumption rate and cost. Prior research had already established that affordability – as expressed in higher cost-sharing for patients with copayment or coinsurance arrangements – has a significant and inverse relationship with drug adherence rates. This required, as a first step, that subjects in the study be dichotomized into ‘low’ or ‘high utilisers’ of antihypertensive drugs.

The author attested to have broken new ground by testing for the interaction between cost-sharing and consumption rate and applying econometric methods to account for overlooked variables in the course of a short-term longitudinal analysis.

Employing quantile regression as the analysis method, Yoon found that for low-adherence patients as a group (those at the 10th percentile), having to pay more than $5 per unit under an existing copayment or coinsurance plan was associated with medication possession ratio (MPR) adherence scores eight or nine points lower than the comparable percentile of patients who paid less. The interactive effect diminished with higher adherence percentiles and in fact, vanished close to the upper limit of adherence percentiles. Overall, nonetheless, Yoon conceded that adherence to a prescribed regimen of vastatin and adjuvant antihypertensive drugs (e.g. diuretics) was high for a sample of working-age patients.

Descriptive and profile analysis suggest that the barriers to adherence are principally intrinsic. At low adherence percentiles, patients were beset by lower-income, poorer education, and suffered other disorders (as indicated by having to take multiple drugs). percentiles of adherence. As well, calculation of the two-stage least squares model showed that there were grounds for concern owing to a higher incidence of co-morbidities amongst low-adherence hypertensive patients. This is a barrier and health concern that the author prefers to mitigate by attacking the symptom of cost. Inevitably, such a skew towards socialized health care management veers toward intervention in copayment and insurance plans, government subsidies, or putting public and political pressure on pharmaceutical companies to reduce margins across the board. Yoon would clearly rather not face up to jobs generation or motivating the maximum number of working-age adults to seek work, albeit both steps are difficult to undertake in the middle of a recession with no end in sight.

DISCUSSION (work in progress)

Patients’ adherence to medications has been an issue facing healthcare professionals for more than 30 years. Many factors play a role in adherence rates such as dosing frequency, adverse effects, duration of therapy, pill burden, etc. Because there is no immediate, recognizable benefits from taking medications, such as statins, patients may be less likely to adhere to their medications than would patients with conditions that have clear symptoms.

Improving adherence to medications may also minimize the financial burden of health-related spending. In 2002, the management of dyslipidemia (as an example of chronic disease) accounted for $30 billion in direct costs and $12 billion in indirect costs of the US healthcare budget. (Sokol, 2005)

The research indicates that there does not seem to be one specific intervention that significantly improves adherence to medications. In fact, one study by Gibson (2006) suggests that issue of adherence is a multifaceted problem and a patient-specific approach may be the optimal method.

The merger between Pfizer and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals announced in January 2009 and approved by Wyeth shareholders on July 21, 2009, creates a present-day opportunity to assess how a strategic alliance bolsters adherence to a drug class. There are no competitive factors to consider in the atorvastatin calcium Cholesterol-Lowering Medication sub-segment since Pfizer enjoys patent protection until 2011. However, there is any number of branded and generic vastatins that physicians and patients can switch to.

For the present, the link between strategic alliances and drug adherence outcomes is far from clear. Pfizer has a long track record of acquiring other pharmaceutical companies, the more recent ones being Wyeth this year and Pharmacia in 2002. But it was the 2000 acquisition of Warner-Lambert that brought Lipitor within the brand stable of Pfizer.

The large body of theory on consumer behavior and drug adherence, as well as the empirical test of patient data from IMS records, affirm that the link between strategic alliance and adherence is complex.

Theoretical frameworks can include the efficiency demonstrated by biotechnology alliances, service quality to describe the entire context of physician-patient relations, and patient self-determination as a barrier to long-term drug compliance.

Owing partly to competitive pressure from other vastatin sub-segments, Lipitor usage and turnover appear to have declined. Adherence is only one explanation.

Intrinsic barriers to sustained use of Lipitor include, it would appear, socio-economic hindrances, the concealed strengths of public primary care units, co-morbidities like CAD, being on multiple drug regimens, and even the absence of physiologic feedback. With this last, we refer to hypertensive patients feeling nothing at all when the dose regimen and vastatin is efficacious.

On the basis solely of the data examined, one would have to accept null hypothesis 1 and conclude that the strategic alliance between Pfizer and Pharmacia in 2002 did not improve drug adherence or unit sales for Lipitor.

Meantime, this study must leave for some future effort the task of assembling all the aforementioned variables and estimating the strength of a network of intermediate outcomes and intervening variables.

LIMITATIONS

Such a broad and multi-disciplinary topic as adherence has some inherent difficulties, most prominently the inclusion and exclusion of particular studies. However, many of the studies excluded from the literature review were randomized controlled trials with, however, insufficient data. This particular research did not link the adherence measure with the health outcome in different patient populations. While it is presumed that increasing medication adherence improves health outcomes, many of the studies reviewed included did not provide such data. Another limitation of this research is the assumption that merger techniques and corporate resources are similar amongst all pharmaceutical companies.

Publication Bias – Publication bias is the selective publication of studies that demonstrate a particular outcome. Therefore, there is a possibility that only studies demonstrating a positive impact on adherence by a particular intervention may have been published, or studies showing a negative impact may never be published. If a publication bias occurs, it can affect the quality and process of the literature review.

References

- American Cardiology Association , 2006

- American Heart Association, Inc. 2009. Cholesterol levels: AHA recommendation. Web.

- Banger-Drowns, R. L. & Rudner, L. M. 1991. Meta-Analysis in Educational Research. ERIC Digest. 1991: 1.

- Bell, S. J., Auh, S. & Smalley, K. 2005. Customer relationship dynamics: Service quality and customer loyalty in the context of varying levels of customer expertise and switching costs. Academy of Marketing Science Journal; 2005; 33 (2): 169-192.

- Berenguer-Contrí, G., Ruiz-Molina, M.-E., & Gil-Saura, I. 2009. Relationship benefits and costs in retailing: A cross-industry comparison. Journal of Retail and Leisure Property, 8 (1), pp. 57-66.

- Breekveldt-Postma, et al. Value Health. 2006.

- Box, J. (1983)

- Chapman RH, et al. Arch Intern Med. 2005

- Chiu, G. & Chang, Y. 2006. A study of the impact of on-line game emotion value creation on players’ switching behavior [in Chinese]. In Khoo, C. and Singh, D. and Chaudhry, A.S., Eds. Proceedings A-LIEP 2006: Asia-Pacific Conference on Library & Information Education & Practice 2006, pages pp. 382-393, Singapore.

- Dagger, T.S., Danaher, P.J., & Gibbs, B.J. 2009. How often versus how long: The interplay of contact frequency and relationship duration in customer-reported service relationship strength. Journal of Service Research 11 (4): pp. 371-388

- Department of Health 2007

- Dezii CM. Managed Care. 2000

- Dholakia, U. M. 2006. How customer self-determination influences relational marketing outcomes: Evidence from longitudinal field studies. Journal of Marketing Research, 109-120.

- Doshi, A.K. 2000. Biopharmaceutical strategic alliances: Interorganizational dynamics and factors influencing FDA regulatory outcomes. Unpublished Dissertation: University of Southern California.

- Glass, G.V, McGaw, B., & Smith, M.L. 1981. Meta-analysis in social research. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Hennig-Thurau, T. & Paul, M. 2006. Can economic bonus programs jeopardize service relationships? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 31(3): 229-240.

- Higgins, J. P.T. & Green, S. (editors). 2008. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.1. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008.

- Hirth, 2006

- Hodgkin, 2007

- Hopfield, 2006

- Hughes (2006)

- Hunter, J.E., & Schmidt, F.L. 1990. Methods of meta-analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Jones, M. A., Mothersbaugh, D. I. & Beatty, S. E. 2002. Switching barriers and repurchase intentions in service. Journal of Retailing: 58-74.

- Lee JK, et al. JAMA. 2006

- Lim, L. S. MD, MPH & Varkey, P. MD, MPH. 2005. E-mail reminders: A novel method to reduce outpatient clinic nonattendance. The Internet Journal of Healthcare Administration. 3 (1): 1.

- McKinsey (2001)

- Needleman, 2001

- Dr. Osterberg and Dr. Baschke, 2005

- Paez (1996)

- Paul, M., Hennig-Thurau, T., Gremler, D.D., Gwinner, K.P., & Wiertz, C. 2009. Toward a theory of repeat purchase drivers for consumer services. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 37 (2): pp. 215-237

- Pelz, 1976

- PharmacoEconomics; 2006

- PhRMA, 2004

- Reimartz, W. J. & Kumar, V. 2003. The impact of customer relationship characteristics on profitable lifetime duration. Journal of Marketing, 67: 77-99.

- Rudd, 1998

- Simons, J. (2003). The $10 Billion Pill: Hold the fries, please. Lipitor, the cholesterol-lowering drug, has become the bestselling pharmaceutical in history. Here’s how Pfizer did it. FORTUNE Magazine. CNNMoney.com. Web.

- Spilker, 2001

- Urquhart, 2001

- Van Arum, P. (2009). Implications of the Pending Pfizer-Wyeth Mega Merger. PTSM: Pharmaceutical Technology Sourcing and Management. PharmTech.com.

- Vanderpoel DR, et al. Clin Ther. 2004

- Volker, 2001

- Walker (2005)

- WellMed (2001

- Yoon, J. 2008. Adherence to prescription drugs and adverse health events for patients with hypertension. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles.

- Yan, Z. 2007. Modeling for patient satisfaction and loyalty of aesthetic plastic surgery, and analysis of affecting factors. Unpublished Dissertation: Taiwan University.

- Yoo, J., Choi, J., Kim, S., Yang, J., & Jong, S. 2009. Factors affecting the switching intention of IPTV subscribers. Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology, ICACT 2, art. no. 4809575, pp. 966-968

- Yoon, J. 2008. Adherence to prescription drugs and adverse health events for patients with hypertension. Unpublished Dissertation: UCLA.