Abstract

Studies indicate the attitude of health caregivers in dental care for people with disabilities to be positive. However, some negative attitude provides a strong barrier to the care and rehabilitation of individuals with disabilities and their integration into the community. This study identifies issues such as cultural values, religious factors, the traditional beliefs attached to the disabled, and educational issues to be some of the critical factors affecting the attitude of caregivers in dental care for people with disabilities in Saudi Arabia. However, scanty research has been done in the field of the attitude of caregivers for people with disabilities in Saudi Arabia. Therefore research into this field was conducted with the objective of determining the attitude of the caregivers mentioned above in the country of Saudi Arabia. The research constituted a questionnaire that was administered to patients with disabilities and healthcare professionals for dental care for people with disabilities. The attitude of caregivers was investigated in the research constituting a sample of 130 participants. The investigation consisted of evaluating the findings based on the Scale of Attitude towards Disabled Persons (STDP) in Saudi Arabia. An interaction with a wide selection of people with disabilities including disabled children and those with physical disabilities were included when conducting the research. The resulting data was analyzed using the spearman’s correlation coefficient, the Kruskal- Wallis coefficient, and descriptive statistics. Findings indicated that the participants indicated a mean score of 100+ 17 positive attitudes. On the other hand, health care professionals did not show any significant deviation from the noted value with a p<0.4. It was further determined that educational levels such as degrees did not vary to any significant extent the attitude of caregivers for the disabled noted at p<0.45. However, there was a significantly poor relationship based on the age of the health care service provider age and a poor score, both at r=0.03. It was therefore concluded that in Saudi Arabia, health care professionals had an inherently positive attitude in dental care for people with disabilities. It was further concluded that issues such as religion and culture, among others, had a strong influence in influencing the attitude of caregivers in dental care for people with disabilities.

Introduction

Dental caries is one of the infectious dental diseases that have been identified to prevail among the population of the disabled in Saudi Arabia. This is also true for people with disabilities such as neurodevelopmental cases, physically deformed, among others. It is true that health care professionals in Saudi Arabia are faced with a number of challenges when working for the disabled in dental care. Such challenges are directly driven by the lack of disability-specific knowledge tailored to address specific dental needs for the disabled, the amount of discomfort that health care professionals experience when working with people with disabilities, and the extent or degree of misconceptions that are associated with people with disabilities, and other beliefs that may be associated with working for the disabled. Therefore, it is clear that the attitude of caregivers for dental care for people with disabilities is directly influenced by their interactions with the disabled and the feelings generated from the interactions. It is important to note that the behavior and attitude of health care professionals towards people with disabilities significantly influence how the disabled feel about themselves. Their attitude may not be overly hostile, but negative attitudes have been identified to cause dental care for the disabled to be ineffective. It has been shown that when a health care professional shows a positive attitude towards a patient with disabilities, the patient’s motivation increases, and the likelihood for a quick recovery is experienced. The widely conducted research has revealed that people with disabilities experience negative treatment from society particularly due to the misconceptions attached to their disabilities. These disabilities towards the disabled are expressed in different ways. They end up inhibiting the patient from attaining their full potentials in their activities. However, other findings indicate that health care professionals exhibit positive attitudes towards the disabled in society. These findings indicate that issues such as age, educational level of the health care provider, cultural beliefs and aspects, clinical experience of the health caregiver, and the site where the practice is conducted have a strong correlation to the attitude of the caregiver to the disabled in the field of dentistry. However, there is a strong debate about the attitude of caregivers from different communities. It is therefore important for each community to conduct thorough research on the attitude of caregivers from their community as analytical data from one community may not reflect the attitude of caregivers in dental care from another community.

Literature review

Andrews notes that true professionalism is characterized by a complete willingness to provide high-quality services to the patient irrespective of the medical condition of the patient [9]. However, providing dental health care for disabled persons requires the dental health care provider’s keenness and positive attitude in providing such services to the disabled. A number of researches have been conducted into the study of the attitude of caregivers in dental care for the disabled in different countries conducted with varying outcomes as discussed in the following review of the literature. Andrews notes that one such study was conducted in New Zealand [8]. Abbott and Wallace found out that dental care for the disabled was severely limited due to the misconceptions that health professionals had towards these patients [1]. Alto confirms that the research done on the attitude of caregivers in dental health care provisions was conducted by classifying the disabled into two categories [6]. In their observation, Aiken, Buchan, Sochalski, Nichols, Powell confirm that one such group consisted of the disabled associated with developmental origin, and another group that group whose disability was acquired later in life [2]. The first category consisted of a group whose disability consisted of mentally retarded patients and those acquired during the developmental stage. Alexeev notes that on the other hand, the next group consisted of patients whose acquired disabilities resulted from trauma and other natural causes [5].

Demographics

Inglis, Rolls, and Kristy see the demographic distribution of the patients with disabilities as being identified to have a strong relationship with the attitude of caregivers for dental care [33]. The research indicated that socio-economic status strongly influenced the attitude since the dental health care provider could not modify the specific treatment necessary for a specific case. Analytically, the management of the patient was important in determining the quality of services delivered to the patient according to the protocols of health care services. Hojat, Gonnella, Nasca, Fields, Cicchetti, Lo Scalzo, et al not that some of the issues that influenced the attitude of the caregivers in dental or oral health care services provisions included the following as discussed below [32].

Pretreatment assessment

Adequate assessment of the condition of the patient at the time of the first visits was critical in determining specific treatment for the disabled person. Thus, contact with the disabled patient was noted to play a critical role in gathering information about the patient. Clear information regarding the patient’s history could be provided by the caregiver of the disabled. Different patients exhibited different tolerance levels when interacting with the dental healthcare provider. In addition to that, other patients had difficulties in communicating and performing other physical activities specific to the treatment.

Patient communication

Arthur, Sohng, Noh, and Kim note that another area of interest in the research was effective communication strategies to the patient [10]. A critical assessment of the patient’s mental status was identified to be critical in establishing a relationship with the patient that could positively influence the attitude of the caregiver. Atkinson argues that some of the patients could not communicate verbally, adding to the challenges of the caregiver in delivering the right information to the dentist [11]. Effective communication may be impaired due to the impairment or disability of the patient.

Behavioral change

Bosworth notes that studies conducted on factors that influenced the attitude of caregivers in dental health care provisions showed a close relation to the behavioral change of the patient [23]. It has been determined that the dentist has to discuss in detail strategies of managing the behavior of the patient when offering dental care services. Sometimes patients with mental retardations are scheduled earlier in the day directly impacting the attitude of the caregiver as such patients at times may prove difficult to handle. Cotroneo, Grunzweig, and Hollingsworth propel the argument further by noting that handling such cases is prone to becoming difficult as such patients may not be conversant with the procedures involved in the process of dental care [31]. Further still, time may be spent in calming down a mentally retarded individual translating to influencing the behavior of the healthcare provider. Brady and Arabi note that sometimes, the movement of the dentist may influence the behavior of the dentist while providing medical appropriate dental care for the mentally disabled may alter the behavior of the patient, having a final impact on the health care provider [24]. Sometimes patients may come with cerebral palsy directly influencing the motor skills of the patient. Brathwaite expresses the understanding that these patients exhibit uncontrolled movements making it more difficult for the health care provider in dental health care provisions to complete offering the necessary dental care services [25]. In addition to that, cardiovascular anomalies that result from medical conditions such as heart murmurs have been identified to have a strong influence on the complications that may arise in the process of providing services to the patient. Other medical conditions that influence the attitude of caregivers are the behavior exhibited by the patient in the process of receiving medical care. These include seizures that are easily controllable using anticonvulsant medications. The frequency of the seizures has a strong correlation to the attitude of the caregiver in dental health care provisions. Al-Abdulwahab and Al-Gain emphasize that during oral care, seizures may occur inhibiting the ability of the dentist to perform specific medical care on the patient [4]. The medical care professional may develop a lasting attitude towards the patient that may overall have a reciprocal effect on the services provided by the healthcare professional. Certain risks such as the risk of aspirations may influence the final outcome of the treatment of the patient as argued by Brink [26].

Bronner confirms that the above study was done with a total of 1273 participants specifically caregivers for the disabled [27]. However, a small number of caregivers participated in this study. The sample size led the researchers to exclude male caregivers in the study. In addition to that, demographic considerations played a critical role in the study. Caregivers formed 3.8 percent of the sample with n=48. Those who did not use English as their primary language constituted 5.4 percent with a sample size of 69 participants, and the sample size for Asians was 9 forming a paltry 0.7 percent of the total sample included in the study. In the research, demographic characteristics and behaviors were tabulated accordingly as illustrated below. Aiken, Buchan, Sochalski, Nichols, and Powell note that the percentage distribution of caregivers within the mean and median of the caregivers was 60 percent of the total population involved in the study [2]. In addition to that, it was estimated that these caregivers had a high school education and above. The population sample was characterized by disabled infants whose mean was in the range of 18 with a median distribution of 15.

Jabbour, in the study, argues that the literacy level was identified to show a normal distribution [34]. Typically, a normal distribution is an important tool in evaluating distributions in statistics. A number of measured quantities have been shown to follow a normal distribution. Bond and Jones note that it also provides useful estimations for statistical measures such as the poison distribution and the binomial approximations [22]. The normal distribution depends heavily on the distribution of a normal continuous variable between the two limits of infinity (negative and positive infinity). To Brush, Sochalski, and Berger, the distribution when making statistical calculations relies on the standard deviation of the distribution and the mean of the distribution [28]. Normally, the distribution provides the variance of the statistic whose curve is characterized by a bell shape, symmetry about the mean, with the maximum value at the apex of the curve, and a total area under the curve being equivalent to one. Different sets of values are used in the calculations based on random samples that are collected for analytical purposes. A number of estimates can be conducted based on the normal curve. These include confidence intervals for the mean of a population, interval estimates, unbiased estimations of population parameters, estimations of the sample populations, and other statistical measures in Burnard and Naiyapatana observations [30].

The research study included a literacy level whose normal distribution was the square of X, a value of 2.0 with a degree of freedom equivalent to 2, and a probability greater than 0.5 was included in the research. The level of knowledge and education of the caregiver was also included in the study. The distribution level of the study showed a normal distribution expressed in the relation as (X2 = 72.1, df = 2, p < 0.05). The mean of the normal distribution was 4.8 and the standard deviation was found to be 1.0. A careful synthesis of the results indicated that two-thirds of the distribution showed a score of 5 or more. Analytically, it was shown that the level of education and knowledge significantly influenced the outcome of the results. Higher education levels indicated the attitude of the dental health care providers to be positively correlated as compared to lower levels of education. It was observed from the findings that higher literary scores occurred for higher education levels compared to lower education levels. Typically, the research was conducted with a number of participants coming from multiple racial backgrounds. Statistical findings indicated a spearman’s to be equivalent of 0.19 equivalents to 95 percent and a confidence interval of 0.13 equivalents of 0.24. A tabulation of the findings is illustrated below as mentioned elsewhere in the report.

From:

Analytically, the findings indicate that low literacy levels strongly influenced the adverse effects on the status of the attitude of the dental health service provider. The above model indicates the worse status of the attitude of dental healthcare caregivers for the disabled to be worse with lower levels of education than with higher levels of education. Below is a further illustration of the attitude of caregivers distributed over different centers. The centers were left anonymous for the purpose of privacy and the results were tabulated below.

The tabulation is descriptive of the behavior of different samples of caregivers for dental health services for the disabled.

From;

Brykezynska notes that Despite convenience samples having been used in the study, participants were selected from a low-income environment with 5 different sites involved in the study [29]. When the literacy level was high for this research, it was noted that the impact on the attitude of the caregiver was higher than when the level of education was low. Further still, low educational levels were strongly associated with health behaviors that were deleterious as per the argument of Bola, Driggers, Dunlap, and Ebersole [21].

Beeman’s further studies conducted to establish the attitude of caregiver’s attitude in dental care towards people with disabilities has been conducted in a number of other stations [15]. To Bentley, some of the findings are at variance with others on the position of healthcare givers’ attitudes towards people with disabilities [18]. An Australian study indicated that nursing students in the nursing fraternity showed a lot more positive attitudes towards people with mental disabilities in dental healthcare services than the general population. These findings were found to be significantly influenced by the level of education of the healthcare giver. Moreover, it was noted that other health care service providers and professionals showed a similar trend in behavior. Further analysis showed that educational strategies integrated into the realm of medical care professionals played a strong role in influencing the attitude of the Medicare personnel. In Australia, it was demonstrated that fresh students who had joined the medical profession and those leaving or graduating from training institutions showed positive attitudes towards people with disabilities. Nonetheless, on further analysis of other research findings on the attitude of caregivers in dental cares for people with disabilities, it was demonstrated by Baumann, Blobner, Binh, and Lan [14] that the attitude towards people with disabilities in dental healthcare provisions was lowest in the nursing faculty compared with other faculties. It was further demonstrated that fresh students had the lowest attitude upon entry into college followed by registered nurses and graduating nurses who showed a stronger attitude towards people with disabilities in dental healthcare services. Other researchers elsewhere have reported different findings. Bjerneld, Lindmark , Diskett, and Garrett argue that nurses showed a generally poor attitude towards people with disabilities and have concluded in their research that they need to educate nurses was critical about the physical needs of disabled people in dental healthcare service provisions [20].

Belcher notes that the variance in findings indicated a significant relationship between a professional’s practice and the attitude of the professional towards disabled people. One such research involved a sample of 250 participants in Texas, USA. 150 of these participants were rehabilitation nurses, 43 of the group were physical therapists, and 57 represented occupational therapists. When the results were tabulated and analytically evaluated, it was demonstrated from the study that occupational therapists had significantly overwhelming higher scores compared to the other two practices [16]. It was further illustrated in the study that age, the duration of exposure in a profession, the social settings, and educational levels had a strong influence in influencing the attitude of caregivers Lee [35].

Hypothesis

On a theoretical level, hypotheses have been formulated to determine the significance of the relationship between the level of education and the attitude of a caregiver towards a disabled person in dental healthcare medical provisions. One such hypothesis is here stated with its null counterpart. Assume that the number of educated people who indicate a positive attitude towards the disabled is X out of a sample of 20 participants. In addition to that, let it be assumed that the analysis is an independent event. Therefore, it is possible to model the variable X after a binomial distribution. Thus the relation or model can be expressed as follows: X—B (20, p).

Ho (Null hypothesis) – Educational level strongly influences the attitude of care in dental healthcare for the disabled.

Hi (Alternative hypothesis) – Educational level has no influence on the attitude of caregivers in dental healthcare for the disabled.

If the null (Ho) hypothesis is true, the hypothetical value for p could be equivalent to 0.25. Therefore, the expression X—B (20, 0.25) could be correct.

Based on the above analysis, one tailed test could be used to provide an appropriate answer. This could include an upper-tail test.

The rejection criteria could be such that the value of x will be found lying in the critical region. Therefore, the expression could be as stated here, if p (X>x) <5% could lead to the rejection of the null hypothesis, taking x to be the test value of the problem. Assume that 7 participants agree that the level of education of the healthcare professional significantly influences the attitude of the healthcare provider attitude towards people with disabilities in dental care. It can be established from cumulative probability tables as tabulated here that, p (X>7) =1-p (X<6). It, therefore, follows that 1-0.7858=0.2141=21%.

Values for the normal distribution from cumulative tables

Theoretically, therefore, the test value for the value of x given as 7 is not in the critical region. Therefore, the adduced evidence is sufficient to reject the null hypothesis. Therefore, there is strong evidence from the study to conclude that educational level significantly influences the attitude of caregivers for the disabled in dental healthcare or oral healthcare services. It is important to note that the value of x used in the analysis is less than 7 that is 6 rather than the actual value which is 7. It is essentially necessarily so because the analysis is focused on finding out if the test value lies in the critical region to afford the right decision. Other tests can be two-tailed tests. However, the above hypothesis was analyzed on a single-tailed test.

1Bihari-Axelsson and Axelsson see the results, therefore, to indicate that there is a strong relationship between the educational level of the healthcare provider and the attitude such a professional could have towards a disabled person in dental healthcare services [19].

Method

In conducting the research, a number of methods were used in the process. Among them was the Scale of Attitudes towards Disabled Persons (SADP). The ATDP scale is widely used and relied upon due to extensive research that has been done on its reliability and accuracy of results. Different methods are used to establish the reliability of the scale. These include the split-half test, a measure of the covariance of the test samples or test items, parallel tests, and test-re-test means. In this research, the average value that inspired confidence in the researchers was determined to be equivalent to 0.8. In addition, it was identified to possess a Cronbach value of 0.795. In addition to that, the content of the research was validated against the literature review that had been conducted on the subject. An items analysis was done with a construct validity constituted measures for comparisons with other similar measures of attitude. In this study, a Form designated as Form B was issued to the respondents with 30 questions. The questionnaire was scaled using a six-point Linkert scale from which respondents could select appropriate options that ranged from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The respondents’ questionnaire had no neural response and they were required to select an option against the relevant statement. Respondents were tested to identify their attitude towards the disabled in providing dental healthcare by healthcare professionals. Responses could be high implying a positive attitude towards the disabled or person with a disability and a low value could indicate a negative attitude towards the disabled. In addition to that, there were no mean scores for the SADP scale.

The reach also aimed to establish the factors that influenced the attitude of caregivers in dental health provisions for people with disabilities. Factors such as age were incorporated into the study. The gender of the participant, the disability status of the respondent, the educational level of the respondent, and the interaction of the disabled were factors included in the study. Findings from the study, descriptive statistics of the study, statistical data, and the variance of the study were discussed below.

The study incorporated administering a total of 405 questionnaires to a similar number of respondents. However, in the study, it was noted that 269 questionnaires were tagged as usable. 55 percent of the proportion were female participants with a sample size of n=148. In the study, 45 percent of the respondents were male whose sample size was n=121. Participants were further categorized into specific age groups. A sample of 167 participants was in the age bracket varying between 18 and 47 years. However, 82 percent of the participants were in the age bracket of 18 and 23 years. The rest of the participants who formed 18 percent of the participating population were in the age bracket of 24 and 47 years. Participants were undergraduate students in the nursing discipline health care providers for people with disabilities who formed a total sample population of 180 individuals. The rest of the population was composed of disabled persons.

In the study, demographic variables were significantly influenced by gender with a p-value of 0.001. It was noted that female participants recorded the highest ATDP score of 119.4 while that for males was 111.6. The p-value for age was 0.203 and the p-value that served as a determinant of a participant’s specialization was 0.359. In addition to the findings, further analysis to evaluate the attitude of caregivers through their experience in interacting with people with disabilities in providing dental healthcare services included asking the dental health professional and caregivers to describe their experiences when interacting with the disabled. Their interactions were first rated on whether they had previous experience interacting with persons with disabilities through a yes/no option in the questionnaire. Results indicated that more than 85 percent of the respondents had previous experience interacting with people with disabilities. The study fell short of providing qualitative information about their interactions with disabled individuals. Participants, in the second phase of the study, were asked to provide information about the frequency of their interactions with people with disabilities. From the respondent’s data, it was realized that interactions on a weekly basis scored the highest mean closely followed by daily interactions. The highest number of participants recorded positive values in terms of their attitude towards people with disabilities in dental healthcare service provisions and a small number showed negative attitudes for a similar group of people.

Findings from this study showed that participants from the medical profession with high professional qualifications showed higher positive values than those with low educational levels. In Bensoussan, Myers, and Carlton’s argument, findings from the study did not indicate the age variable to have any significant effect on the attitude of the caregivers towards the disabled persons [17]. The scores from the groups did not register significant differences to afford any biases in attitude towards people with disabilities in dental care. However, mixed results were identified for people in either category of the gender divide. The mean attitude score for females was higher than that for males. Analytically, therefore, the difference in the mean score for male participants with female participants was a critical point of discussion in order to effect positive attitude changes. While both participants in the gender divide could provide services for the disabled in dental healthcare provisions; an effective service delivery could yield more satisfactory and fulfilling results for people with disabilities. It is conclusive from the research that males are likely to serve better in administrative positions.

Austin, Champion, and Tzeng identify results yielded due to research conducted on the interactions of people with disabilities that yielded results to be interesting [12]. Quantitative data showed an overwhelming response in which 85 percent of respondents reportedly affirmed that they had at various points interacted with people with disabilities. On the other hand, qualitative data from the study did not yield valuable information that could be used to influence a decision. However, from the study, one could note that the number of responsibilities assigned to an individual interacting with people with disabilities in the realm of dental care had a strong influence on the attitude of the caregiver towards the person with disabilities. Bastien could further note that the frequency of interactions had a strong correlation with the behavior of the caregiver and professional oral health provider in dental care [13]. The higher the frequency of interactions, the higher the number of stressors and the greater the influence on the attitude of the health professional and caregiver in dental care provisions to the disabled.

Further analysis of the results indicated that more frequent exposures to the disabled by a health professional in dental care could enhance their attitude and maintain a positive attitude towards the disabled.

This review of the literature takes one to one of the other studies conducted to determine the attitude of healthcare givers towards the disabled in dental healthcare includes one that was conducted among students in the city of Jeddah in Saudi Arabia. This study focused on evaluating the behavioral attitudes of the group in relation to periodontal healthcare status for the disabled in Saudi Arabia.

Materials and Methods

In the study, a population of 258 participants was recruited. A multistage sampling technique was the sampling tool used in the process. The random sample was stratified targeted at achieving a level equivalent to 0.05. To ensure the results were well generalized, a target value whose power was 0.80 percent was used in the process. The sampling was only restricted to Saudi participants living in Jeddah. The required number of participants was selected through a stratified sampling technique. Two major levels of the study consisted of professional caregivers and professional healthcare professionals. In addition to that, the disabled participated in the research by filling in the questionnaires on a number of factors that affect them. Each stratum was proportionately represented in the study. The researcher ensured that sufficient representation was done on the population to ensure accuracy of results in the study targeting a cross-section of participants. The researcher further ensured that male and female participants were represented in the study. Of the representative sample, 49.2 consisted of male representatives and 50.8 percent of the participants were females. The attached questionnaire was administered to each of the participants. The questionnaire was administered to provide information about the age of the participants, gender, position of the caregiver in relation to the disabled, the health status of the participants whether disabled or not, respective ages, dental healthcare needs of the individuals under the care of a healthcare provider, dental insurance, specific dental healthcare needs, the frequency with which the dental patient visits a dental healthcare clinic, efficiency and response time to the patient with dental healthcare problems from a dental healthcare provider, distance traveled in accessing dental healthcare services, and to identify if the need for influenced their access to dental Medicare health provisions. The demographic description of professional dental healthcare providers and caregivers in the research was tabulated below. The distributions were influenced by their attitude towards the disabled with periodontal disease.

The distribution is as illustrated below.

Sample of tabulated results

The sample table with tabular results shows the distribution of the participants and their respective responses in their attitude towards dental medical care for people with disabilities. The results further inform the research about the significance of the results of the findings.

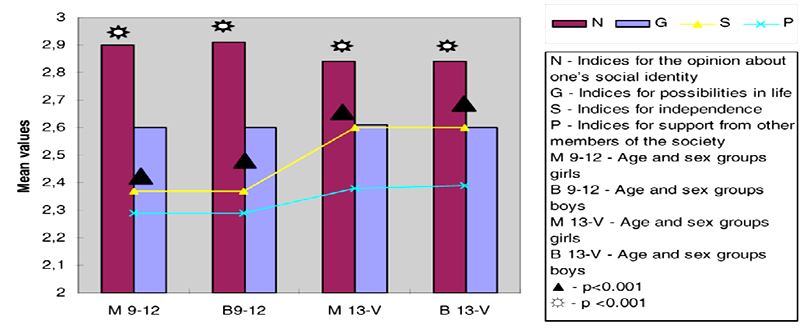

The research indicates that there were strong feelings of sympathy for the disabled, hence a strong feeling of self sympathy as illustrated below.

The disabled respondents did not feel a grain of fear at each other and the self-awareness index was strong among the disabled. In the research, suppressive social issues such as stigmatization tended to affect the disabled, particularly the children as illustrated above.

The researcher further incorporated measures to improve the precision and reliability of the results. One critical measure was subjecting the measurement scale to a rigorous psychometric analysis by Abbott and Wallace [1].

In the survey, the spearman coefficient in the scaling of the results was identified to lie between 0.18 and 0.85 of the correlation. The alpha coefficients were identified to lie between 0.88 and 0.91. A principal factor analysis was done which yielded three subscales. The reliability coefficients of the subscales varied between 0.55 and 0.73 that consisted of three subscales which included pessimism-hopelessness, optimism-human rights, and behavior-misconceptions.

Results

A statistical difference was noted between both genders in their attitude towards the disabled in dental healthcare provisions. A significant difference was noted also among participants with different educational levels of the participants and their physical orientations. Further findings indicated a correlation coefficient due to spearman registering a value of 0.03 and 0.003 respectively. A number of respondents did not respond as required, but for the respondents who responded appropriately, they were identified to register a mean age of 32.4±6.4 while their respective experiences and interaction with the disabled in dental healthcare provisions were in the range of 8.0± 2.2 years. In addition to that, their attitudes with respect to their education levels were evaluated. A mean score of 100±17 was noted. In the study, a mean difference was noted between the female and male participants. The insignificance of the difference was noted to be (p<0.08) on a chi-square test with attitudes varying between 97±6.4 and (105±2.6) for both males and females respectively.

Further research based on the three subscales included pessimism-hopelessness, optimism-human rights, and behavior-misconceptions particularly for the caregivers showed varied results. The sample population of the caregivers was equivalent to 41 and the sample population of the dental nurses was equivalent to 122. The results are tabulated below.

Discussion of Results

The literature review by several researchers revealed that statistical findings in the same field showed the coefficient of correlation of spearman to be equivalent to 0.19 equivalents to 95 percent and a confidence interval of 0.13 equivalents to 0.24. The findings indicate a strong relationship between the literacy level of the medical profession and the attitude towards people with disabilities in dental healthcare provisions. Low literacy levels strongly influenced the adverse effects on the status of the attitude of the dental health service provider. The above model indicates the worse status of the attitude of dental healthcare caregivers for the disabled to be worse with lower levels of education than with higher levels of education as is noted by Aiken, Clarke, Sloane, Sochalski, Busse, and Clarke H, et al [3].

In addition to that, findings from the study did not indicate the age variable to have any significant effect on the attitude of the caregivers towards disabled persons. There were no significant differences between the groups in the scores about positive or negative attitudes towards the disabled in dental care. From the study, one could note that the number of responsibilities assigned to an individual interacting with people with disabilities in the realm of dental care had a strong influence on the attitude of the caregiver towards the person with disabilities. It was further noted that the frequency of interactions had a strong correlation with the behavior of the caregiver and professional oral health provider in dental care.

The study further revealed that in Saudi Arabia, professional healthcare providers’ attitude towards dental care for people with disabilities was positive. Partly, that was influenced by the educational level of the service providers and the cultural and religious values of the population in general. In addition to that, the attitude of caregivers in dental care towards the disabled showed a significant relationship with knowledge. The more the Medicare professionals were educated in dental care for the disabled, the more positive the attitude of the caregiver and the medical professional was towards the person with disabilities. The results demonstrate that people including healthcare professionals develop personal attitudes towards the disabled based on the frequency of their interactions with disabled people needing dental healthcare services. Individual experiences with the disabled, the age of the participants, and general knowledge of the caregivers also influenced the attitude of caregivers and their sympathy towards the caregivers. In addition to that, those who had had no prior experience in dental care for the disabled indicated negative attitudes towards the group. Healthcare providers and other medical professionals who did not interact frequently with people with disabilities were more likely to develop stereotypically negative attitudes in dental care for people with disabilities in Saudi Arabia.

It was noted from the research that physicians who participated in the research showed a more positive attitude towards people with disabilities in dental care for the disabled than nurses. This was partly attributed to a wider extent of knowledge the physicians had compared to nurses. Nurses recorded a greater percentage of misconceptions about dental care for the disabled coupled with a high percentage of pessimism about the disabled in dental care compared with caregivers for people with disabilities. This was thought to be partly attributed to the frustrations nurses experienced due to limited medical facilities in offering dental care for people with disabilities. Inadequate rehabilitation facilities were conjured to be one of the reasons for the attitude of nurses in the dental healthcare fraternity.

Behavioral misconceptions were also strongly correlated to age. Even though some studies do not find such a relation to influencing the attitude of caregivers, yet other studies indicate significance in the relationships. Interesting findings elsewhere indicated that younger healthcare providers and medical professionals showed positive attitudes compared with older professionals. The assumption for these findings was that younger professionals may have been educated on healthcare for the disabled more than older professionals. In Saudi Arabia, the working experience did not show any significant relationship or influence on attitude by the health professionals towards the disabled in dental healthcare. In addition to that, the participants in this study could be assumed to have reached the ultimate plateau about a positive towards the disabled. While in the literature review, some researchers found a significant relationship between gender and attitude towards the disabled in dental healthcare provisions, in Saudi Arabia there was no significant difference in attitude due to the gender of the participants towards the disabled. It, therefore, could be concluded that gender did not show any significant effect attitude of the medical professionals towards the disabled in dental healthcare services. Therefore, the positive attitude by the caregivers and medical professionals could be a critical element in contributing towards treating or handling people with disabilities in dental care warmly while genuinely accepting them and establishing cordial relationships with them while handling them. Nonetheless, the research was affected by a number of limitations. Among these limitations was the ability to gather qualitative data that could be of value in influencing the outcome of the results. In addition to that, some noise variables were not factored into the analysis of the final results, hence interfering with the actual findings of the study. It was further noted that referral manuals were not used in the study, the needs of the disabled were not targeted in the study, and time was limited for the study. There were no measures to establish any evidence of comorbidity where the relationship between conditions that led to the disability of an individual and the clinical management of the patient with a disability could be managed. Secondary conditions were not factored in the research that could influence medical care for the disabled such as isolation was not critically evacuated in the research design. Other critical data such as economic conditions of the disabled could not be established with absolute certainty to guarantee they’re being factored into the research. Third-party support for the disabled was complicated with a myriad of paperwork that offered little or no support at all in influencing the attitude of the caregiver and the health professional positively.

Recommendations

To improve the attitude of caregivers towards dental care of people with disability in Saudi Arabia, a number of recommendations were arrived at based on the just concluded research. The need to improve self-awareness among the healthcare community and caregivers is important in enhancing the relationship between the client or the disabled person and the healthcare provider. In addition to that, dental healthcare professionals need to be furnished with the dental history of the disabled patient, hygiene beliefs of the dental disabled patient, and the prevailing oral health of the disabled person. Further recommendations target nurses and dental healthcare personnel. They need to use standardized methods which have gone through validity tests to ensure results obtained from patent assessments are reliable to enhance relationships positively. Some of the tools recommended for use in assessing the oral health of the disabled patient include those that are used to validate long term care in a onetime trial, validation tolls in oncology patients, residential care settings, and the World Health scale for grading in clinical trials for patients with disabilities when being offered dental healthcare services. Other recommendations included caregivers encouraging positive attitudes between the disabled while enhancing their relationship with a similar group of disabled persons. Caregivers should be trained on the risk of exposures these disabled persons are subjected to and methods of endeavoring to overcome them. There should e the provision of continuing education to the caregiver, the nurses, the healthcare professionals’ dental healthcare providers on the importance of positive attitudes with the disabled and the need to for good oral health and positive relationships. Given the significance of the attitude of the oral health practitioners towards dental care of people with disabilities, its worth developing programs to increase the intensity in educating stakeholders in dental healthcare for the disabled to enhance and improve their relationships further with positive results.

Conclusion

The need to positively enhance the attitude of healthcare givers in dental care for people with disabilities in Saudi Arabia is a critical task in the healthcare discipline. Disabled persons share similar feelings with other people. Moreover, they are disadvantaged due to their medical conditions, but the full feelings of humanity prevail. A strong association between the literacy levels of the caregivers and the attitude scores indicates without doubt the need for caregivers for the disabled to be taken for further training on the need to develop positive attitudes towards the persons under their care. In addition to that, the resulting data analyzed using the spearman’s correlation coefficient, the Kruskal- Wallis coefficient, and descriptive statistics showed that more work has to be done in educating both the caregiver and the disabled in matters of attitude towards each other. That is based on findings that indicated that the participants registered a mean score of 100+ 17 positive attitudes. On the other hand, health care professionals did not show any significant deviation from the noted value with a p<0.4. It was further determined that educational levels such as degrees did not vary to any significant extent the attitude of caregivers for the disabled noted at p<0.45. However, there was a significantly poor relationship based on the age of the health care service provider age and a poor score, both at r=0.03. It was therefore concluded that in Saudi Arabia, health care professionals had an inherently positive attitude in dental care for people with disabilities. It was further concluded that issues such as religion and culture, among others, had a strong influence in influencing the attitude of caregivers in dental care for people with disabilities. In the light of the above findings, it is important for the healthcare authorities to take education to all demographic distributions that are tailored to address issues of age and attitude towards those with disabilities in dental care.

References

- Abbott P, Wallace C.Talking about health and well-being in post-Soviet Ukraine and Russia. Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics, 23(2), 181-202; 2007.

- Aiken LH, Buchan J, Sochalski J, Nichols B, Powell M. Trends in international nurse migration: The world’s wealthy countries must be aware of how the “pull” of nurses from developing countries affects global health. Health Affairs, 23(3), 69-77; 2004.

- Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski JA, Busse R, Clarke H, et al. Nurses’ report on hospital care in five countries. Health Affairs, 20(3), 43-53; 2001.

- Al-Abdulwahab SS, Al-Gain SI, Attitudes of Saudi Arabian health care professionals towards people with physical disabilities. Asian Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal, 14(1), 63-70; 2003.

- Alexeev V. Thinking in the old way and trying to live in the new. Journal of Management in Medicine, 13(4-5), 339-345; 1999.

- Alto WA. Emergency health services in rural Vietnam. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 16(4), 422-424; 1998.

- Anders RL, Kanai-Pak M.Karoshi: Death from overwork… a nursing problem in Japan? Nursing & Health Care, 13(4), 186-191; 1992.

- Andrews MM. Educational preparation for international nursing. Journal of Professional Nursing, 4(6), 430-435; 1988.

- Andrews MM.Cultural perspectives on nursing in the 21st century. Journal of Professional Nursing, 8(1), 7-15; 1992.

- Arthur D, Sohng KY, Noh CH, Kim S.The professional self concept Of Korean hospital nurses. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 35(3), 155-162; 1998.

- Atkinson S. Political cultures, health systems and health policy. Social Science and Medicine, 55(1), 113-124; 2002.

- Austin J K, Champion VL, Tzeng OCS. Crosscultural comparison on Nursing image.Journal of International Nursing Studies, 22(3), 231-239;1985.

- Bastien JW. Community health workers in Bolivia: Adapting to traditional roles in the Andean community.Social Science and Medicine, 30(3), 281-287; 1990

- Baumann LC, Blobner D, Binh T, Lan PT. A training program for diabetes care in Vietnam. Diabetes Educator, 32(2), 189-194; 2006.

- Beeman P. Nursing education, practice and professional identity: A transcultural course in England. Journal of Nursing Education, 30(2), 63-67; 1991.

- Belcher D. Profiles. A long way from home: Two American RNs begin Humanitarian work in Sudan. American Journal of Nursing, 105(1), 110-111; 2005.

- Bensoussan A., Myers SP, Carlton AL. Risk associated with the practice of traditional Chinese medicine: An Australian study. Archives of Family Medicine, 9 (10), 1071-1078; 2000.

- Bentley C. Primary health care in Northwestern Somalia: A case study. Social Science and Medicine, 28(10), 1019-1030; 1989.

- Bihari-Axelsson S. Axelsson R. The role and effects of sanatoriums and Health resorts in the Russian Federation. Health Policy, 59(1), 25-36; 2002.

- Bjerneld M, Lindmark G, Diskett, P, Garrett MJ. Perceptions of work in humanitarian assistance: Interviews with returning Swedish health Professionals.Disaster Management & Response, 2(4), 101-108; 2004.

- Bola TV, Driggers K, Dunlap C, Ebersole M.Foreign-educated nurses: Stranger in a strange land? Nursing Management, 34(7), 39; 2003.

- Bond ML, Jones ME. Short-term cultural immersion in Mexico.Nursing and Health Care, 15(5), 248-253; 1994.

- Bosworth TL. International partnerships to promote quality care: Faculty groundwork, student projects, and outcomes. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 37(1), 32-38; 2006.

- Brady H. Arabi Y. The challenge of a multicultural environment for critical care nursing in Saudi Arabia. Middle East Journal of Anesthesiology, 18(3), 541-550; 2005.

- Brathwaite D. Mentoring relationships while conducting international research. Journal of Multicultural Nursing & Health, 8(1), 36-41; 2002.

- Brink P.J.Taking a student into the field. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 12(1), 7-8; 1990.

- Bronner M. Bridges of barriers to success: The nature of international student experiences in nursing. Journal of Nursing Education, 21(7), 38-41; 1982.

- Brush BL, Sochalski J, Berger AM. Imported care: Recruiting foreign nurses to U. S. health care facilities. Health Affairs, 23(3), 78-87; 2004.

- Brykezynska G. Nurse education in Poland. Senior Nurse, 12(1), 21-24; 1992.

- Burnard P. Naiyapatana W. Culture and communication in Thai nursing: A report of an ethnographic study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 41(7), 755-76; 2004.

- Cotroneo M, Grunzweig W, Hollingsworth A. All real living is meeting: The task of international education in a nursing curriculum. Journal of Nursing Education, 25(9), 384-386; 1986.

- Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Nasca TJ, Fields SK, Cicchetti A. Lo Scalzo A, et al. Comparisons of American, Israeli, Italian and Mexican physicians and nurses on the total and factor scores of the Jefferson Scale of Attitudes toward physician-nurse collaborative relationships. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 40(4), 427-435; 2003

- Inglis, A., Rolls, C., & Kristy, S. (1998). The impact of participation in a study abroad Programme on students’ conceptual understanding of community health nursing in a developing country. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 28(4), 911-917.

- Jabbour S. Health and development in the Arab world: Which way forward? British Medical Journal, 326(7399), 1141-1143; 2003.

- Lee N. Learning from abroad: The benefits for nursing. Journal of Nursing Management, 5(6), 359-365; 1997.