Mental and physical health forms the underpinning of a happy and fulfilling life. Equable access to high-quality healthcare services is indicative of high standards of living. Despite the US government’s best efforts to do away with inequalities in the healthcare system, disparities in accessibility and health outcomes regarding the treatment of African Americans have not been eradicated. Identifying the main factors that contribute to race being a strong social determinant of health is the first step toward establishing a more equitable healthcare system.

Members of African American communities might avoid seeking mental health counseling due to multitudinous factors, such as stigma, mistrust, religious and spiritual beliefs, affordability and accessibility, misdiagnosis, and feeling culturally misunderstood. However, research suggests that “attitude is a unique predictor” in whether professional help will be sought out, and it is heavily influenced by stigma (Fripp & Carlson, 2017, p. 80). As the research conducted by Fripp and Carlson (2017) indicates, African Americans who reported espousing heavier stigmatized views were less likely to seek professional psychological help. Stigma toward mental health disorders is prevalent among other racial and ethnic communities nationwide. Nevertheless, African Americans are significantly more inclined to experience the negative consequences of stigma because, pertaining to a racial minority, they frequently face other social adversities (Eylem et al., 2020). The compound effect of small injustices, inequalities, and everyday struggles shapes people’s attitudes that ultimately foster an inclination to forgo counseling.

Meanwhile, the willingness of African Americans to participate in mental health services is also conditioned by existing barriers to help-seeking. A study published in Children and Youth Services Review examined a number of factors related to the barriers among African American youth. The following themes were listed: “child-related factors; clinician and therapeutic factors; stigma; religion and spirituality; treatment affordability, availability, and accessibility; the school system; and social network” (Planey et al., 2019, p. 190). As it can be seen, the barriers that influence the decision to engage in or forgo mental health services pertain to different spheres of life and are of various scopes. On the other hand, Planey et al. (2019) also identified themes that served as facilitators. These included “child mental health concerns; caregivers’ experiences; supportive social network; positive therapeutic factors; religion and spirituality; referrals and mandates by parents and gatekeepers; and geographic region” (p. 190). Thus, the facilitating factors are just as diverse in nature as their counterparts. Analyzing the influence of facilitators on African Americans’ attitudes toward mental health services can provide useful insight that will help in dismantling the barriers.

Mental health is not unique in being overlooked as a result of bias, stigma, or mistrust. The latter, in particular, combined with perceived racism in healthcare and everyday racism, leads to delays in preventive screening among African American men, according to an article published in Behavioral Medicine (Powell et al., 2019). Concurrently, having to systematically face racism across virtually all domains of life might cultivate and reinforce medical mistrust. Furthermore, racism leads to “poor health outcomes and economic disadvantage among African Americans” (Taylor, 2019, para. 18). Studies indicate that lifelong discrimination aggravates the risks of developing health conditions, such as hypertension (Forde et al., 2020) and diabetes (Bacon et al., 2017). The former, in particular, can frequently lead to higher risks of heart failure, stroke, and peripheral artery disease. According to the American Heart Association, cardiovascular disease is a “primary cause of disparities in life expectancy between African Americans and whites” (Carnethon et al., 2017, p. e1). Thus, while limited healthcare access can be, in part, engendered by the racially prejudiced social environment, the deleterious effects of racism eat away at African Americans’ health, putting them in greater need of medical services.

On the other hand, when the need arises, and African Americans choose to seek professional medical help, its quality can be questionable. Cultural racism within the medical sphere cultivates bias and discrimination toward racial minorities. As a result, medical attention received by the members of African American communities is inferior in quality in comparison with that received by whites (Williams et al., 2019). Furthermore, some medical professionals can be misguided due to incomplete scientific evidence, which negatively influences the health care African Americans receive, examples of which include “poorer treatment across ages for acute, chronic and post-operative pain” (Tiako & Stanford, 2020, p. 2). Therefore, it can be concluded that racism both deters African Americans from participating in medical services and deters medical professionals from providing high-quality services to members of African American communities.

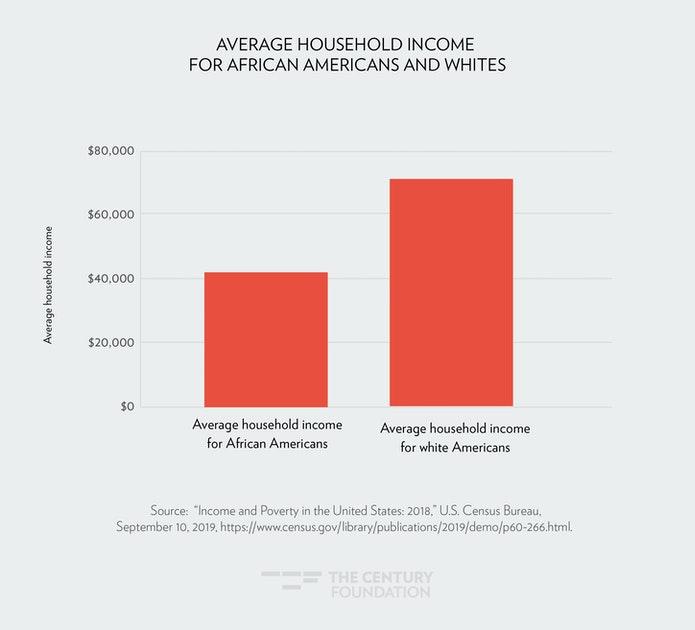

Other factors that might be either strengthened or single-handedly brought on by racism also contribute to the limited access to healthcare among African American communities. Accordingly, as is emphasized by Williams et al. (2019), structural racism continues to perpetuate residential segregation – despite it being illegal for over half a century – and has a significant negative impact on health. The main pathway by which segregation influences health is by being strongly correlated with socioeconomic status (SES). This, in turn, conditions having access to quality education, better job opportunities, and medical care, as well as lower or higher rates of poverty, crime, and violence in the neighborhood. Poor living conditions make it more challenging to engage in healthy habits and practices. Moreover, poor education often translates into lower income, which makes it difficult to break the cycle by moving to a wealthier neighborhood. Taylor (2019) also points out that residing in a certain geographic area can pose difficulties in accessing health care due to insufficiently developed transportation, and especially to people with limited incomes. Therefore, racism can negatively influence the SES, which is related to a number of other factors limiting access to healthcare.

Despite the undeniable negative effects of interpersonal, cultural, and structural racism on the accessibility of healthcare among African American communities, some communities suffer these effects significantly less than others. According to a study done by Shepherd et al. (2018), African Americans reported good access to medical services, overall satisfaction with healthcare providers, and low levels of racism or poor treatment. The study was conducted in a Mid-Western jurisdiction where the presence of racial minorities is comparatively low, which provided interesting insight. However, it was noted that some participants’ still reporting poor treatment was not to be overlooked. Meanwhile, research indicates that there is a need to study the issue through a different lens, examining intersectionalities to acquire a better understanding of the matter (Lewis & Van Dyke, 2018). However, in view of the disproportionately high mortality rates among African Americans due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the influence of racism on health outcomes is still starkly evident and needs addressing (Jean-Baptiste & Green, 2020). Thus, experiences of African Americans related to healthcare differ across the nation; however, racism remains a key factor in health outcomes.

Overall, there are numerous variables that result in limited access to healthcare among African American communities. While attitude and stigma toward mental health influence peoples’ decisions to seek counseling, other barriers, such as medical mistrust and racism in healthcare, are also present. Moreover, structural racism contributes to geographical segregation associated with other negative consequences, including poverty and limited access to quality education. Although some studies indicate general satisfaction and good access to medical care among certain African American communities, further research is required to improve the situation nationwide.

References

Bacon, K. L., Stuver, S. O., Cozier, Y. C., Palmer, J. R., Rosenberg, L., & Ruiz-Narváez, E. A. (2017). Perceived racism and incident diabetes in the Black Women’s Health Study. Diabetologia, 60(11), 2221-2225. Web.

Carnethon, M. R., Pu, J., Howard, G., Albert, M. A., Anderson, C. A., Bertoni, A. G., Mujahid, M. S., Palaniappan, L., Taylor, Jr. H. A., Willis, M., & Yancy, C. W. (2017). Cardiovascular health in African Americans: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 136(21), e1-e31.

Eylem, O., De Wit, L., Van Straten, A., Steubl, L., Melissourgaki, Z., Danışman, G. T., De Vries, R., Kerkhof, A.J., Bhui, K. & Cuijpers, P. (2020). Stigma for common mental disorders in racial minorities and majorities a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 20, 1-20. Web.

Forde, A. T., Sims, M., Muntner, P., Lewis, T., Onwuka, A., Moore, K., & Diez Roux, A. V. (2020). Discrimination and hypertension risk among African Americans in the Jackson heart study. Hypertension, 76(3), 715-723.

Fripp, J. A., & Carlson, R. G. (2017). Exploring the influence of attitude and stigma on participation of African American and Latino populations in mental health services. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 45(2), 80-94. Web.

Jean-Baptiste, C. O., & Green, T. (2020). Commentary on COVID-19 and African Americans. The numbers are just a tip of a bigger iceberg. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 2(1), 100070.

Lewis, T. T., & Van Dyke, M. E. (2018). Discrimination and the health of African Americans: The potential importance of intersectionalities. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(3), 176–182. Web.

Planey, A. M., Smith, S. M., Moore, S., & Walker, T. D. (2019). Barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking among African American youth and their families: A systematic review study. Children and Youth Services Review, 101, 190-200. Web.

Powell, W., Richmond, J., Mohottige, D., Yen, I., Joslyn, A., & Corbie-Smith, G. (2019). Medical mistrust, racism, and delays in preventive health screening among African-American men. Behavioral Medicine, 45(2), 102-117. Web.

Shepherd, S. M., Willis-Esqueda, C., Paradies, Y., Sivasubramaniam, D., Sherwood, J., & Brockie, T. (2018). Racial and cultural minority experiences and perceptions of health care provision in a mid-western region. International Journal for Equity in Health, 17(1), 1-10. Web.

Taylor, J. (2019). Racism, inequality, and health care for African Americans. The Century Foundation. Web.

The Century Foundation, December 19, 2019, Average household income for African Americans and whites.

Tiako, M. J. N., & Stanford, F. C. (2020). Race, racism and disparities in obesity rates in the US. Journal of Internal Medicine, 288(3), 363.

Williams, D. R., Lawrence, J. A., & Davis, B. A. (2019). Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annual Review of Public Health, 40, 105-125. Web.