Introduction

There is a range of contributing factors that increase the likelihood of obesity development in adults (National Institutes of Health, 2019). In general, such factors include physical activity, energy consumption, and macronutrient intake. As alcohol not only influences the total energy consumed by an individual but also has an impact on the metabolic pathways, which may change fact storage and oxidation. Therefore, it is imperative to conduct a systematic review of research on the connections between obesity and alcohol intake to explore evidence that points to the existence of the problem.

Background of the Problem

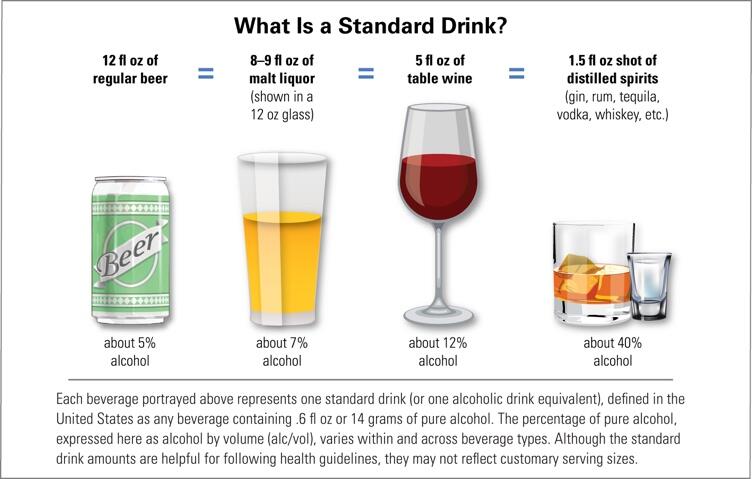

Prior to delving into studies on the topic, it is essential to explore the notion of a standard drink and what it means for consumption and health. According to the report by the National Institutes of Health (2019), the amount of liquid in a glass, bottle, or can does not match how much liquor a person drinks because of different alcohol contents. Within the US regulations, one alcoholic drink equivalent contains approximately fourteen grams of pure alcohol (see Figure 1). This amount can be found in 1.5 ounces of distilled spirits (40% alcohol), 5 ounces of wine (12% alcohol), and 12 ounces of generic beer (5% alcohol) (National Institutes of Health 2019). Therefore, taking into consideration the amounts of alcohol contained in one regular drink is essential to further the understanding of links between consumption and obesity.

Within the framework of public health, alcohol represents a preventable behavioural risk factor that contributes to health deterioration. According to the report by Boccia, Villari, and Ricciardi (2015), approximately 2.3 people die from the excessive use of alcohol. More than a half “of these deaths occur from NDCs, including cancers, CVD and liver cirrhosis” (Boccia et al. 2015, p. 25). Importantly, the per capita consumption of alcohol among adults is higher in developed countries with greater wealth distribution, which is essential to consider when exploring studies on the topic.

While alcohol consumption represents a behavioural risk factor to health decline, overweight and obesity refer to metabolic risk factors. Based on Boccia et al.’s (2015) report, at least 2.8 million people die annually from being obese or overweight. It is explained by the influence of increased BMI on blood pressure, certain cancers, heart disease, and diabetes (Boccia et al. 2015). It is notable that in the past, obesity and overweight were considered issues relevant only for high-income countries. However, today, they are on the rise in both low- and middle-income regions, and in urban settings specifically.

As mentioned in the same report, throughout 2011, more than forty million children aged 5 and lower were overweight, with the two-thirds of them living in developing countries (Boccia et al. 2015). This presents a significant healthcare challenge to prevent obesity not only among adults but among children whose well-being can be significantly compromised by increasing weight.

Conflicting Evidence

Beyond adding energy to meals, alcohol has shown to encourage the intake of food. The research conducted by Traversy and Chaput (2015) represents a vital addition to the study of obesity and alcohol use in regards to the updated information on the issues. Through synthesising evidence from multiple research, the scholars concluded that heavy drinking had been associated with weight gain. For example, alcohol promotes adiposity that increases weight gain. Energy attained through alcohol consumption adds to energy from other sources, which increases its density (Traversy & Chaput 2015).

Food intake has shown to follow the consumption of alcohol due to the learned connections between eating and drinking. In addition, liquor intake was also linked to hormones associated with satiety. Apart from this, the increase in hunger through the contribution of alcohol intake could emerge through several central mechanisms. According to Traversy and Chaput (2015, p. 129), “the effects of alcohol on opioid, serotonergic, and GABAergic pathways in the brain all suggest the potential to increase appetite.” Nevertheless, despite the growing amount of evidence suggesting that the frequent intake of alcohol could predispose individuals to gain weight and reaching long-term obesity, there is also research that points otherwise.

First, Traversy and Chaput (2015) mentioned that alcohol intake could increase the expenditure or energy, most likely because of its significant thermogenic effect. Also, it has been suggested that the energy from the ingested alcohol is wasted because of the inefficiency in the hepatic microsomal ethanol-oxidizing system. This system is encouraged to work with the increased intake of alcohol, which contributes to rising induction due to chronic alcohol intake (Traversy & Chaput 2015). Although, the extent to which energy wasted from the consumption of regular drinking contributes to the prevention of weight gain is unclear. The research, thus, concludes that evidence for the relationships between the intake of alcohol and obesity is conflicting and is limited by important barriers that preclude

Beardsley (2014) analysed the likelihood of obesity occurrence as related to alcohol intake among adult university employees. Through conducting baseline visits with 700 participants with the median age of 51 years, it was possible to observe a significant negative correlation between the consumption of beer and body fat percentage (BF%) in women but not in men. The increased frequency of liquor intake was found to have a positive correlation with the waist-to-hip ratio in males. For women, the decline in median Body Mass Index (BMI) and BF% was linked to the increase in wine intake frequency (Beardsley 2014).

Therefore, the results of the study were somewhat surprising as it was expected to find stronger connections between alcohol intake and BMI increase. As shown in Beardsley’s (2014) research, a higher frequency of wine consumption was linked to lower body fat percentage. This points to the need to study the relationship between BMI and alcohol intake further as a range of factors may predict the possibility of obesity occurrence.

The study by Beulens, van Beers, Stolk, Schaafsma, and Hendriks (2012, p. 2) is notable to the current discussion. The researchers aimed to investigate the impact of average alcohol consumption on the distribution of fat distribution, sensitivity to insulin, and “adipose tissue secreted proteins among healthy middle-aged males with abdominal obesity” (Beulens et al 2012, p. 3). The randomised, controlled cross-over design trial involved thirty-four men aged between thirty-five and seventy years old with increased waist circumference. Over four weeks, the participants were asked to drink 450 millilitres of red wine (forty grams of alcohol) or non-alcoholic red wine.

At the end of the study, it was concluded that the moderate consumption of alcoholic beverages was not linked to variations in body weight and abdominal fat contents (Beulens et al. 2012). Despite the fact that the researchers observed a 10% increase in adiponectin, it was not linked to the changes in weight or fat distribution (Beulens et al. 2012). These results correlate with the study by Beardsley (2012) who also did not find a correlation between moderate consumption of alcohol and obesity.

Shelton and Knott (2014) explored the connections between alcohol-associated calorie intake and obesity and overweight. The quantitative research was meant to derive the adult intake of alcohol from volume of consumption and the type of drinks in the Health Survey for England. Using survey-adjusted logistic regression, the researchers could calculate the likelihood of obesity occurrence as related to alcohol consumption. For men, the mean intake of calories from alcohol was 27% of the recommended intake while for women, the percentage was 19% on their heaviest day of drinking (Shelton & Knott 2014).

Positive associations between alcohol-derived calories and obesity were found, which suggests that there is relevant data to show that there is a connection between the two variables. It is also notable that the study mentioned the differences in hazardous alcohol consumption in the US and the UK, pointing to the variability in drinking preferences and behaviours. This data is vital for considering the role of drinking culture as a predictor of alcohol use and its relation to obesity. In both countries, policymakers should consider regular consumers of alcohol. Thus, future research opportunities are associated with studying the connection between other conditions and alcohol-related calories.

Park, Park, and Hwang (2017) explored the problem of abdominal obesity as linked to alcohol consumption among middle-aged normal-weight adults. The researchers hypothesised that bodyweight could be associated with obesity-related health risks. The quantitative study implied cross-sectional research using complex sampling. Both men and women were included in the study, with data on alcohol drinking patterns assessed with the help of self-report questionnaires. Both males and females involved in the study had higher odds for developing abdominal obesity when their occasional quantity of consumed alcohol increased.

However, weight and waist circumference did not increase among those adults who consumed fewer than two drinks per week. Importantly, males who consumed alcohol every day in large quantities had higher odds of having abdominal obesity (Kase, Piers, Schaumberg, Forman & Butryn 2016). In both sexes, the rate of alcohol use was not associated to abdominal obesity in adults of normal weight. These findings suggest that the amount of liquor consumed influenced the increase in waist circumference, thus impacting health risks related to obesity. This calls for the need to control alcohol drinking habits to lower the odds of adults developing abdominal obesity.

Chao, Wadden, Tronieri, and Berkowitz (2018) examined the role of managing alcohol intake when implementing lifestyle interventions among overweight or obese patients as well as those diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. It was found that the consumption of alcohol was not associated with weight loss at year one for participants of the intensive lifestyle intervention. On the contrary, those who abstained from consuming alcohol lost 5.1% ± 0.3% of their initial weight at year 4 of the intervention (Chao et al. 2018). Heavy drinkers who consumed alcohol consistently could only lose 2.4% ± 1.3% of their weight (Chao et al. 2018).

Participants of the intensive lifestyle intervention who did not consume alcohol during the program lost 1.6% ± 0.5% more weight compared to individuals who drank alcoholic beverages at any time throughout the intervention. These findings show that decreasing the consumption of alcohol could play an essential role in weight management among obese and diabetic individuals.

Biological Effects

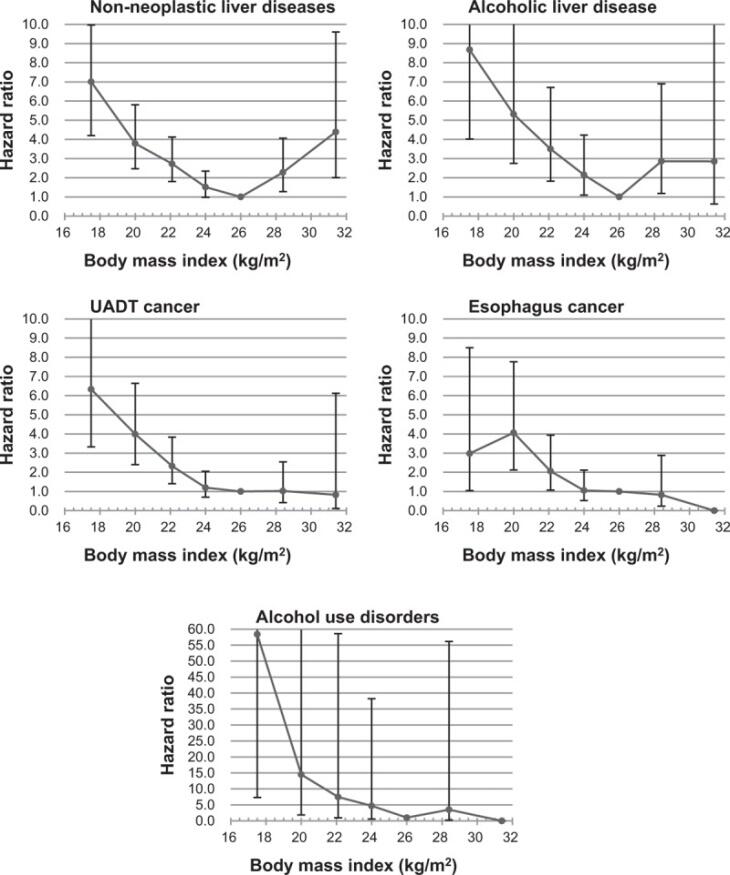

From the perspective of biological implications of alcohol consumption and increased body mass index, it is imperative to consider the study by Yi, Hong, Ti, and Ohrr (2016). The researchers investigated the impact of the two variables on mortality from liver diseases and cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract. Between 2004 and 2010, 107,335 men with the mean age of 58.8 years took part in a postal survey. Data collected from the questionnaires was connected to national morality records. After the adjustment for confounders, hazard ratios for cause-specific deaths were measured (see Figure 2).

The findings of the study suggest that high consumption of alcohol was linked to the increased mortality for approximately 70% of mortality associated with non-neoplastic liver disease, around 60% for cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract, and nearly 70% for deaths from alcohol use disorder (Yi et al. 2016). Importantly, the combined impact of low BMI and high consumption of alcohol was between 2.25 and 3.29-fold higher compared to the additive impact of each factor for liquor-associated conditions (Yi et al. 2016). High BMI, on the other hand, contributed to the deaths from non-neoplastic liver disease.

Miller et al. (2018) explored the influence of alcohol consumption and obesity on breast cancer development among middle-aged women. The quantitative study analysed population data on breast cancer incidence, the consumption of alcohol, psychological distress, and obesity. It is notable that ecological relationships were identified as related to breast cancer and alcohol consumption. Strong correlations were found between stress factors and alcohol use as well as between obesity and stress.

BMI showed to be higher in instances relative to controls associated with life history. Therefore, case-control findings imply that lifetime BMI among women can be a notable risk factor when considering the prevalence of obesity before forty years of age (Miller et al. 2018). Psychological stress is an essential contributor to increased alcohol consumption and obesity but not to the incidence of cancer and was differently associated with smoking and alcohol (Marks 2018).

These findings are essential for illustrating the importance of reducing alcohol consumption and normalising BMI among women before they turn 40 to reduce breast cancer risks. Similar to Yi et al. (2018) who underlined the need to reduce alcohol consumption and BMI to manage cancer occurrence in the population, Miller et al. (2018) came to the same conclusion. This suggests that the biological effects of obesity and increased alcohol consumption adversely influence the population’s health.

Another article that is important to consider in the current discussion was done by Sookoian and Pirola (2016) who investigated the extent to which moderate alcohol consumption (MAC) was safe in overweight and obese individuals. The scholars note that there were conflicting findings as to the impact of the average consumption of alcohol drinks being either detrimental or beneficial. For example, through analysing quantitative evidence from multiple studies, Sookoian and Pirola (2016) could conclude that MAC could have a favourable effect on liver fat accumulation.

However, the extent to which regular consumption of alcohol can become harmful or beneficial remains unclear. Importantly, the issue was found to be associated with sex, which suggested that sexual dimorphism played a significant role in predicting whether MAC would either positively or adversely influencing liver health (Sookoian & Pirola 2016). Nevertheless, the researchers underlined the issue that the effects of MAC on overall health outcomes could be highly scrutinised. Data on alcohol assessment and patterns of drinking could be significantly limited qualitatively, especially in studies involving populations. Therefore, it remains unclear as to how safe can moderate alcohol consumption may be in overweight and obese people.

Burton and Sheron (2018, p. 987) asserted that no level of alcohol consumption could improve health regardless of consumption rates and patterns. The researchers conducted a “systematic analysis from the 2016 Global Burden of Disease, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study that involved 195 countries and territories.” The burden of alcohol consumption was particularly relevant among individuals aged between 15 and 49, for whom alcohol was the leading cost of disability-adjusted life-years. Evidence collected for the stated showed the magnitude of harm that alcohol produces, with the prevalence increasingly emerging (Burton & Sheron 2018).

Therefore, the research by Burton and Sheron (2018) suggested that alcohol represents a significant global health problem. Any decrease in health-associated risks is being outweighed by the range of adverse implications of consuming alcohol, including cancer. The authors also pointed to the need to reduce alcohol-associated harms through price regulation and taxation as well as the physical availability of alcoholic beverages for the population. For the UK, the outlook on controlling alcohol consumption with the help of progressive, evidence-based strategies already enacted in Scotland as well as similar measures planned for Wales and Northern Ireland, with England acting as the placebo control.

Latino-Martel et al. (2016) examined the likelihood of cancer development as related to the consumption of alcohol, increased weight, and the lack of physical activity. Data was collected from more than a hundred meta-analyses, interventional trials, and pooled analyses to find connections between cancer and various nutritional patterns, including alcohol consumption. Based on the evidence categorised as probable or convincing, nutritional factors were differentiated into two types (Latino-Martel et al. 2016).

On the one hand, contributors increasing the risk of cancer occurrence included alcohol, obesity and overweight, the consistent consumption of red and processed meats, salt, and beta-carotene supplements. On the other hand, factors lowering the likelihood of cancer development include increased physical activity, healthy eating of fruits and vegetables, dairy products, and fibre.

Summary

To conclude the systematic review of literature, it must be mentioned that evidence pointing to the connections between alcohol consumption and obesity is conflicting. Some scholars found that the use of alcohol could lead to the accumulation of fat and increased obesity occurrence. However, others showed that the associations between the two variables are insignificant, which meant that they could not be connected without further research. The key takeaway from the analysis is that future studies on the topic is needed to reveal more evidence regarding the contribution of alcohol consumption to obesity.

Nevertheless, a conclusion can be made that both alcohol consumption and obesity occurrence contribute negatively to the health outcomes of the population. This points to the need to dedicate legislative and regulatory efforts to address the problem of excessive alcohol use while also encouraging a healthy lifestyle through positive dietary and exercise choices (Leasure, Neighbors, Henderson & Young 2015). Full randomised controlled trials represent an opportunity for future studies on the topic for testing the effectiveness of interventions targeted at reducing alcohol use to influence the decrease in obesity occurrence. Urgently, the population requires many interventions to take the consumption of alcoholic beverages under control to guarantee positive health outcomes among individuals.

Reference List

Beardsley, J 2014, The relationship between alcohol intake and body fat percentage in adult university employees. Web.

Beulens, J, van Beers, R, Stolk, R, Schaafsma, G & Hendriks, H 2012, ‘The effect of moderate alcohol consumption on fat distribution and adipocytokines’, Obesity, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

Boccia, S & Ricciardi, W 2015, A systematic review of key issues in public health, Springer, New York.

Burton, R & Sheron, N 2018, ‘No level of alcohol consumption improves health’, The Lancet, vol. 392, no. 10152, pp. 987-988.

Chao, A, Wadden, T, Tronieri, J & Berkowitz, R 2018, ‘Alcohol intake and weight loss during intensive lifestyle intervention for adults with overweight or obesity and diabetes’, Obesity, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 678-681.

Kase, C, Piers, A, Schaumberg, K, Forman, E & Butryn, M 2016, ‘The relationship of alcohol use to weight loss in the context of behavioral weight loss treatment’, Appetite, vol. 99, pp. 105-111.

Latino-Martel, P, Cottet, V, Druesne-Pecollo, N, Pierre, F, Touiallaud, M, Touvier, M, Vasson, M-P, Deschasaux, M, Le Merdy, J, Barrandon, E & Ancellin, R 2016, ‘Alcoholic beverages, obesity, physical activity and other nutritional facts, and cancer risk: a review of the evidence’, Critical Reviews in Oncology/Haematology, vol. 99, pp. 308-323.

Leasure, J, Neighbors, C, Henderson, C & Young, C 2015, ‘exercise and alcohol consumption: what we know, what we need to know, and why it is important’, Frontiers in Psychiatry, vol. 6, pp. 156.

Marks, R 2018, ‘Obesity, depression, and alcohol linkages among women’, Advances in Obesity Weight Management & Control, vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 246-249.

Miller, E, Wilson, C, Chapman, J, Flight, I, Nguyen, A-M, Fletcher, C & Ramsey, I 2018, ‘Connecting the dots between breast cancer, obesity and alcohol consumption in middle-aged women: ecological and case control studies’, BMC Public Health, vol. 18, no. 460, pp. 1-14.

National Institutes of Health 2019, What is a standard drink? Web.

Park, K-Y, Park, H-K & Hwang, H-S 2017, ‘Relationship between abdominal obesity and alcohol drinking pattern in normal-weight, middle-aged adults: the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2008-2013’, Public Health Nutrition, vol. 20, no. 12, pp. 2192-2200.

Shelton, N & Knott, C 2014, ‘Association between alcohol calorie intake and overweight and obesity in English adults’, American Journal of Public Health, vol. 104, no. 4, pp. 629-631.

Sookoian, S & Pirola, C 2016, ‘How safe is moderate alcohol consumption in overweight and obese individuals?’ Gastroenterology, vol. 150, no. 8, pp. 1698-1703.

Traversy, G. & Chaput, J 2015, Alcohol consumption and obesity: an update’, Current Obesity Reports, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 122-130.

Yi, S, Hong, J, Yi, J & Ohrr, H 2016, ‘Impact of alcohol consumption and body mass index on mortality from non-neoplastic liver diseases, upper aerodigestive tract cancers, and alcohol use disorders in Korean older middle-aged men: prospective cohort study’, Medicine, vol. 95, no. 39, pp. 4876.