Introduction

There are alarming indications that suicide incidences need immediate as well as effective measures specifically addressing reduction or minimization among adolescents as a considerable chunk of successful attempts, especially in the U.S., indicate a grave situation. Likewise, the influence of elderly actions reflected and magnified via interconnectivity and the new media allows suicide stories to travel faster and reaching a wider young audience, such as the trendiness of suicide in Japan.

Other considerations include people mobility and migration of peoples where children and adolescents have to migrate with their parents to a different place with a different culture, thereby incidence of indifference, animosity, and unfamiliarity increases the risk for adolescents and children. Lack of time for parental guidance and bonding due to economic pressure or long work hours also contribute to the already fragile family system.

This paper shall outline and explore risk factors, the connection of depression and its symptoms to suicide ideation, as well factors that contribute to suicide ideation among adolescents with emphasis on the role of the school, peers, family, and the school as a central support system.

Predictors of Treatment Response

Research-based psychotherapy is generally considered effective with clinically distressed children and adolescents (Weisz et al., 1995), but many youths fail to achieve clinical remission over the course of treatment and have been a concern to professionals. Studies point to several factors related to the youth, caregiver, and treatment context that contribute to sub-optimal treatment outcomes for clinically disturbed youths.

Brent et al. (1998) found that higher cognitive distortion and hopelessness, among other factors, cause the poor response to treatment for clinically depressed youth who received either cognitive behaviour therapy, family-based treatment, or supportive therapy. Initial problem severity, early-onset, family adversity such as low socioeconomic status, low social support and parental psychopathology, as well as older youth age, was also found by Southam-Gerow et al. (2001) as contributory factors in the failure to treat youth with anxiety disorders.

Reid and Hammond (2001) likewise established that youth with conduct disorder which is characterized by early-onset, serious aggressive behaviour, negative parenting, and family adversity, tend to be less responsive to cognitive behavioural treatments. Following is a study on the gap of treatment failure among teens with suicide tendencies:

Teen Suicide and Depression

The majority of suicide attempts and suicide deaths happen among teens with depression, with about 1% of all teens attempts suicide, and about 1% of those suicide attempts results in death, meaning about 1 in 10,000 teens dies from suicide. Adolescents who have depressive illnesses had higher suicidal thinking and behaviour as most teens who have depression think about suicide and between 15% and 30% of teens with serious depression who think about suicide go on to make a suicide attempt (Carter and Minirth, 1995).

Depression upon onset stays after a few hours or a few days, and while it lasts, it can seem too heavy to bear. Teens who are depressed or in an intense, sad mood that lingers almost all day, almost every day for 2 weeks or more, it may be a sign that the person has developed major depression, sometimes called clinical depression, which is beyond a passing depression — an illness in need of treatment. Serious depression is also called bipolar disorder, characterized by extreme low moods or major depression, as well as extremely high moods or manic episodes (Carter and Minirth, 1995).

Serious depression on both major depression and bipolar illness involves a long-lasting sad mood that does linger and a loss of pleasure in things teens enjoyed. It is also characterized by thoughts about death, negative thoughts about oneself, a sense of worthlessness, a sense of hopelessness that things could get better, low energy, and noticeable changes in appetite or sleep. Depression distorts a person’s viewpoint, making them focus on their failures and disappointments and exaggerate negative things. Depressed thinking can convince someone there is nothing to live for, and loss of pleasure that is part of depression can be further evidence that there is nothing good about the present. Likewise, hopelessness can make it seem like there will be nothing good in the future and that nothing can be done to change things for the better. Low energy can make every problem, even small ones seem like too much to handle (Carter and Minirth, 1995).

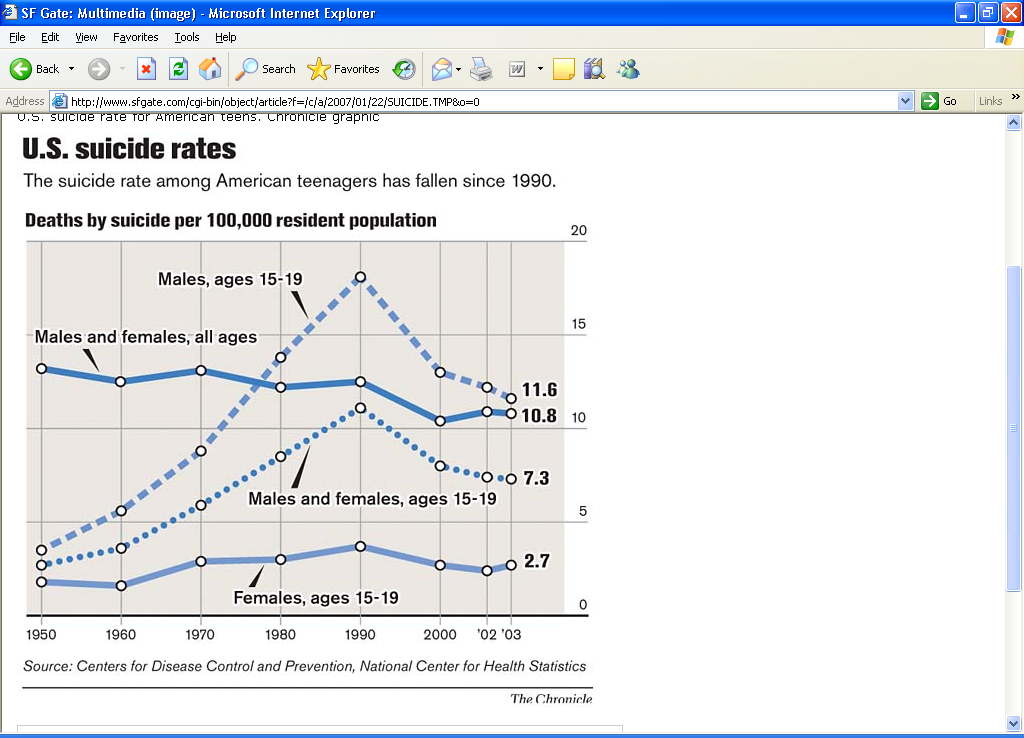

Teenage Suicide Overview

According to Fisher (2006), there are about 500,000 young people who attempt suicide each year and about 5,000 succeed. In the US alone, every two hours and 15 minutes, a person under age 25 years old completes a suicide making it the leading cause of death for young people between the age of 15 and the age of 19. Fisher (2006) underscored the approval and release of the Garrett Lee Smith Memorial Act authorizing $82 million to be used for screening, assessment and counselling for a period of three years aimed at reducing youth suicide. It is expected to help educators address the problem of adolescent suicide, but already, Fisher (2006) opined that unless classroom teachers and building administrators serve as an early warning system, the attempt would hardly work.

The Healthy Place (2007) proposed that due to shifts in the US population, by the year 2010, approximately 33% of the US population is expected to be Asian/Pacific Islander, African American, Native American, or of Hispanic origin. As such, higher levels of poverty and relatively lower levels of education among ethnic/racial minority groups may place some members of those groups at significant risk for mental health problems. This would imply that cultural and language barriers and lack of awareness by primary care physicians in identifying mental illness, especially for ethnic/racial minorities, would make it more difficult for some to access the US health care systems. Likewise, low rates of health care insurance among minorities are complicating factors aside from the serious gap between the need for mental health and substance abuse treatment and their accessibility or availability to minorities.

The serious implications of the above includes:

- “Primary care physicians are less likely to detect mental health problems, including depression, among African American and Hispanic patients than among whites.

- Women who are poor, on welfare, less educated, unemployed and from ethnic/racial minority populations are more likely to experience depression.

- Ethnic/racial minorities were less likely to receive treatment for depression in 1997. Of adults who received treatment, 16% were African American, 20% Hispanic, and 24% white.

- Ethnic/racial minorities were less likely to receive treatment for schizophrenia in 1997. Of adults who received treatment, 26% were African American, 39% were white” (Healthy Place, 2007)

In addition, Healthy Place (2007) proposed that risk factors for substance abuse are the same across cultures so that all people who fall into the following groups are at risk regardless of racial/ethnic subgroup. Ethnic/racial minorities are more likely to have such risk factors and may be at greater risk for substance abuse and addiction. For these growing groups of mobile peoples, risk factors include low family income, residence in the Western U.S., residence in metropolitan areas with populations greater than 1 million, tendency to use English rather than Spanish, lack of health insurance coverage; are unemployed, have not completed high school, have never been married, reside in households with fewer than two biological parents, have a relatively high prevalence of past-year use of cigarettes, alcohol, and illicit drugs (Healthy Place, 2007).

Brofenbrenner (1979) proposed that adolescent development is interlocked with their surroundings so that the lack of balance within this system causes ‘trouble’ to adolescents. Likewise, studies have always associated suicidal ideation among adolescents with their perception and interpretation of their surroundings and psychological states.

Henry et al. (1993), however, pointed out that there are several psychological risk factors in adolescent suicide, such as:

- hopelessness

- depressive symptoms

- feelings of worthlessness

- family and extra-familial subsystems.

Specifically, under the last family and extra-familial subsystems, issues may include parental death, poor parental care, high parental expectation, poor family communication, poor academic achievement, and break-up with a boyfriend or a girlfriend.

For studies in other countries that include North America (Huff, 1999), England (Hollis, 1996), European countries (Tomori et al., 2001) and Asian countries (Ho et al., 1999), parent-child conflict was the main stress contributor to suicidal ideation and attempt. Other studies conducted in the Netherlands (Verkuyten & Thijs, 2002), Australia (Bond et al., 2001) and America (Rigby & Slee, 1999) found peer victimization such as acts of teasing, name-calling and fighting as another stress that affected adolescents’ social self-esteem, school satisfaction, depressive symptoms, anxiety and suicidal ideation. In some studies, however, academic pressure was a source of stress leading to suicidal behaviours among adolescents in the USA (Shagle & Barber, 1995), Japan (Iga, 1981), Korea (Juon et al., 1994) and Mainland China (Greenberger et al., 2000). Consequently, these interpersonal conflicts with family members, friends and academic stress are the main factors in adolescent suicidal ideation. This made Apter (1982), and Zweig et al. (2002) emphasize the need to understand the adolescents’ concerns as well as meeting their needs and building up their surrounding support systems. The human ecological perspective needs to strengthen the protective functions of the family, peers and school, such as enhancing good family relationships, feeling close to parents, feeling liked by friends and feeling connected to the school to prevent adolescent suicide.

Support Systems

Family – in the family system, cohesion is built in the sense of caring, warmth, protection and support (Cox, 1999), which is a significant factor that offsets stress and reduces the development of depression (Reinherz et al., 1989) as well as suicidal behaviours (Rubenstein et al., 1989). Emphasis is on parental support fund to be an effective protective factor against the negative effects of developmental stress on adolescent depression and suicidal ideation.

In a study conducted by Sun and Hui (2007, p 304) under the severe suicidal ideation group, all subject adolescents revealed having frequent conflicts with their parents or guardians who had unrealistic expectations of their academic achievements and severely criticized their poor performance. They admit to not feeling valued I their family, displaying a sense of helplessness and hopelessness. Irrational and fierce scolding usually led to suicidal attempts as a way of coping. Overall, it was found that family support and understanding is very important for adolescents who have suicidal ideation.

Peers – Friends are potential resources as adolescents have the tendency to seek peer support in times of trouble or even suicidal thoughts (Bee-Gates et al., 1996). Likewise, peer support also serves as a protective factor moderating the negative effect of family stress on adolescents’ depression and anxiety (Ohannessian et al., 1994) so that failure to obtain both parental and peer support contribute to feelings of worthlessness, hopelessness, depressive symptoms, and subsequent suicidal ideation (Harter et al., 1992). It was then established that family and peers were effective buffering systems for adolescents in stressful situations leading to positive management of stress (Herman-Stahl et al., 1996).

Sun and Hui (2007, p 305) also reported that conflict with classmates or being victimized made the respondents felt worthless and depressed. They perceived that teasing could not be stopped or avoided and that they felt helpless. Turning to their friends in times of trouble or even when they have conflicts in their family gave the respondents a sense of worthiness, perceiving their friends as trustworthy, understanding and caring, decreasing suicidal tendencies.

School – Students’ sense of belonging or feeling of connection to the school as well as being valued by classmates and teachers are promising school variables that result in liking school, enjoying class, having a concern for others and having conflict-resolution skills (Soloman et al., 2000). This also leads to lower depressive symptoms, social rejection, peer victimization, delinquency and drug use. Colarossi & Eccles (2003) added that adolescents perceiving higher levels of teacher support, in addition to parental and peer support, reported having higher self-esteem and lower levels of depression, showing the vital role of teachers in promoting student’s sense of school belonging, student guidance and counselling. Sun and Hui (2007, p 308-309) added that in a study conducted in Hong Kong, they were able to establish that school guidance and counselling may have an important role in reducing adolescents’ suicidal risks, promote support in the adolescents’ families, school and peer systems and strengthen the adolescents’ resiliency.

While the study (Sun and Hui, 2007, p 309-310) also revealed that peer support was important at school, most of the adolescents did not consider their teachers as able to give them emotional support. They also believe that their relationship with their teachers was close enough to disclose personal problems. Likewise, they were not used to seeking emotional support from their teachers. Those who had a close relationship with their teachers found their teachers taking the initiative in taking care of them, willing to listen to them, and were able to understand their feelings as well as offer advice. They feel comfortable disclosing their problems and felt esteemed and supported after disclosure valuing their relationship with their teachers, especially when there were family problems. The teachers gave them a sense of belonging in the school (Sun and Hui, 2007).

Fisher (2006) suggested that everybody else involved, basically support group members from the family, peer and school must be:

- on the watch for the signs of adolescent suicide

- must know how to respond when the situation calls for it

- confront this epidemic

- provide space within schools for students to disclose their feelings to a trusted adult.

Prevention is always the most basic need for every potential suicide aimed by most people involved, basically those who are close to victims. Therefore, it is necessary to inform young people and their family members of the necessary precautionary signs to recognize suicidal tendencies. Signs of potential suicide are enumerated as follows:

- talking about committing suicide

- having trouble eating or sleeping

- drastic changes in behaviour

- withdrawal from friends or social activities

- giving away prized possessions

- had previous suicide attempts

- taking unnecessary risks

- preoccupation with death and dying

- lost interest in personal appearance

- increased use of drugs or alcohol (Fisher, 2006)

- violent, rebellious or running away behaviour

- marked personality change

- persistent boredom

- the decline in quality of school work

- frequent physical complaints that could be related to emotions such as stomach ache, headache or fatigue

- intolerance of praise or rewards

- complaints of being a bad person or being rotten inside

- verbal hints like “I won’t be a problem for you much longer

- becoming suddenly cheerful after a period of depression

- hallucinations, bizarre thoughts or other signs of psychosis (Lelchuk and Allday, 2007).

However, it is notable that although experts may provide these popular signs and may actually have conducted counselling to victims, other symptoms which parents and support group members may miss due to the subtlety are those cited by a self-confessed suicidal that includes:

- leading very normal lives

- depressed at times, but try to hide it from people and do not make it obvious they are hiding something

- obviously lack the presence of mind, sometimes

- stare at a distance

- sigh a lot

- difficulty in making them talk

- would rather listen to favourite music (Tadeja, 2007).

Educators as Members of the Support System

Fisher (2007) proposed that disclosure is possible through conversations with peers and adults, in their writing, and as earlier posted, in their behaviour. The response is most crucial as teachers or educators may serve as “the early warning system that alerts the social and health services system to a youth in need” (p 10). It has been noted that since most adolescent students do not know their school nurse, social worker or psychologist very well, “the teacher is often the person whom they reveal their problems so that despite lack of training or support, the teacher becomes the broker of services for youths at risk of suicide,” (p 10). It is to be noted that at the adolescence stage, students already have an idea about “off-limits” topics in school, although they will discuss and write about these things, including topics on death and suicide-related ones, when these are given permission. Fisher (2006) enumerated ways where educators may subtly encourage openness of students:

- “You can say it.” Ensure students can discuss delicate issues through access and provision of books and information exploring these topics in the school or classroom library. A teacher may also directly share or give a specific book to the student to indicate that “you can talk with me about this” (p 11)

- More directly. Fisher (2006) cited the Hoover High School in San Diego, California, where teachers read aloud Paul Fleischman’s book Whirligig about a teen who attended a party, rejected, got drunk and attempted suicide while driving.

- Let the students know they are supported. While this may be a forbidden topic, it has come to appoint that students become aware these are real issues with support systems available.

One discouraging observation presented by Fisher was, “Certainly students’ anxieties, and worries enter into the classroom discourse in a variety of ways and on a regular basis. As teachers, we can try to avoid these situations of disclosure by avoiding any personal conversations with students, either in writing or in discussions,” which is very contrary to the more positive approach of Fisher’s noted teacher Marti Singer who said, “Once we have read a paper, there is a contract between the person and us… We need to respect the student’s possible anxiety in telling the story at all… we need to ascertain that the writer needs and what our role is to be – advice-giver, classifier, info-giver, listener, facilitator, friend”.

According to Fisher (2006), educators and administrators must approach the symptoms known to them professionally by recognizing the pain while offering help and professional assistance and asking the person what he or she would expect others to do. The educators must become comfortable responding to students, and those who have lost someone to suicide must be encouraged to write about their thoughts, emotions, reactions and experiences as writing allow educators to identify students at risk at the same time serving as therapeutic to students.

The American Psychiatric Association Alliance (APAA) have used writing intervention to identify students at risk of suicide using an essay project titled “When Not To Keep a Secret” developed in response to fears in school violence which has been identified to discrimination-based suicides among teens (Fisher, 2006). The idea was to provide students with an opportunity to air and come out in the open about their secrets, enabling them to reflect on their experiences, breaking a confidence, and trusting an adult. The project was focused on school violence but surprisingly, 90% of the essays submitted focus on suicide. The partnership with the Yellow Ribbon campaign provided guest speakers, training, online advice, a hotline, request-for-help cards, and information across the country.

Fisher (2006) encouraged educators to confront the issue of adolescent suicide directly, avoid blaming neither the victim nor his or her parents, provide students with an opportunity to seek and receive the help they need as they negotiate the trials, tribulations and triumphs of adolescence.

In addition, Sun and Hui (2007) proposed the implications for school guidance and counselling in reducing adolescents’ suicidal risks, promoting support in the adolescents’ families, school and peer systems, as well as strengthening the adolescents’ resiliency confirming Apter’s (1982) developmental and preventive ideas with regards to troubled adolescents and the troubled interlocking systems. They suggested the need to create a guidance-oriented and caring school environment, counsellors and teachers who can take an active role in developing and inviting school community by building up close, mutually respectful, accepting, caring and supportive relationships in the school setting. The school can promote harmonious teacher-student relationships, strengthen teacher and peer support systems, and reduce peer victimization. These will lead to promoting students’ sense of school belonging and enabling schools to act as a support system for students from dysfunctional families, offset stress and gain support.

Likewise, the findings (Sun and Hui, 2007, p 310) revealed that teachers need to equip themselves with certain qualities to act as potential emotional supporters for their students by building up a friendly and reliable rapport with their students. The teachers’ initiative is considered a key in inviting students to approach them when they are in trouble. School counsellors can equip teachers with pertinent knowledge and skills such as active listening and empathy as they interact with their students. Likewise, timely referral to the school counselling team (of the trained school counsellor, social workers and psychologists) must be given to students who appear to be in trouble.

The school, in addition, may utilize a student support system by organizing peer helper programs and help students build up social support networks, designing multiple social skills training programs, enhancing peer relationships and developing a caring relationship within the school (Sun and Hui, 2007, p. 309).

Since the family is a valuable factor in the support system as well as in the formation of suicidal ideations, the school should provide a venue for hosting family relationship enrichment programs. This will help equip students and their parents with effective communication and conflict-resolution skills. Parent education programs may focus on encouraging parents to show an interest and patience in listening to their children, to attend to their feelings and underlying psychological needs, as well as give corresponding guidance and support. In addition, counsellors may also help parents appreciate their children as to who they are and what they could be, as against judging their children on their academic achievement. This aims to build an understanding and to care home environment (Sun and Hui, 2007, p. 309).

Since students tend to think that suicide is a way to cope with distress, the school’s role must empower adolescents’ personal strength through systematic school-based social and emotional learning programs for positive youth development. These may focus on teaching students to appropriate coping skills, positive thinking, stress and emotional management and self-efficacy to handle life events. The school must highlight active help-seeking as one of the effective coping strategies and encourage students to take the initiative in seeking help in times of need (Sun and Hui, 2007, p. 310).

Conclusion

As already mentioned elsewhere, the school has become the ground for adolescents due to limited family time presented by economic as well as highly-emphasized individuality among adults. It is therefore very important that middle schools must deal with children and adolescent behavioural problems, most specifically suicide, depression, and other behaviour issues.

While family matters seem to be an obstacle that the school cannot interfere with, as mentioned earlier, programs aided and supported by the government must be emphasized among families and parents in order to gain maximum support. Schools must take advantage of the government initiatives to address problems such as family skills orientation and support programs, minimize internal school conflict among students by banning bullying, promote social integration among students, especially those who belong to minority groups, as well as advocate a friendlier relationship between teachers and students.

Likewise, it is much needed that while writing and opening up of pent-up emotions and problems are very positive as indicated in programs and school group initiatives, confidentiality, as well as strategic handling of student cases of depression, bullying, and inter-related factors, be carefully considered.

References

- American Association of Suicidology (2005). “Youth Suicide Fact Sheet.” From Suicidology.org

- Apter, S.J. (1982). Troubled Children / Troubled Systems. Pergamon Press.

- Bee-Gates, D., Howard-Pitney, B., LaFriomboise, T. and Rowe, W. (1996). “Help-seeking behavior of native American Indian high school students.” Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 27 (5), 495-499.

- Bond, L., Carlin, J.B., Thomas, L., Rubin, K. and Patton, G. (2001). “Does bullying cause emotional problems? A prospective study of young teenagers.” British Medical Journal 323 (7311), pp. 480-484.

- Brent, D.A., Perper, J.A., Goldstein, C.E.. Kolko, D.J., Allan, M.J., Allman, C.J., & Zelenak, J.P. (1998). “Risk factors for adolescent suicide: a comparison of adolescent suicide victims with suicide inpatients.” Archives of General Psychiatry 45, pp. 581-588.

- Brofenbrenner, U. (1979). The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Harvard University Press.

- Carter, Les and Frank Minirth (1995) The Freedom from Depression Workbook. Thomas Nelson.

- Colarossi, L.G. & Eccles, J.S. (2003). “Differential effects of support providers on adolescents’ mental health.” Social Work Research 27 (1), 19-30.

- Cox, M. J. (1999). Coflict and Cohesion in Families. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Fisher, Douglas. (2006). “Helping Teenagers Get Through the Worst: Suicide.” Phi Delta Kappan 87, June, pp. 784-86.

- Greenberger, E., Chen, C., Tally, S.R., & Dong, Q. (2000). “Family, peer, and individual correlates of depressive symptomatology among U.S. and Chinese adolescents.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 68 (2), pp. 209-219.

- Healthy Place (2007). “Depression in Racial / Ethnic Minorities”.

- Herman-Stahl, M. Stemmler, M., & Petersen, A.C. (1996). “Approach and avoidant coping: implications for adolescent mental health.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 24 (6), pp. 649-665.

- Ho, B.K.W., Hong, C., & Heok, K.E. (1999). “Suicidal behavior among young people in Singapore.” General Hospital Psychiatry 21, pp. 128-133

- Hollis, C. (1996). “Depression, family environment, and adolescent suicidal behavior.” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35 (5), pp. 622-630.

- Huey, S.J., Henggeler, S.W., Rowland, M. D., Halliday-Boykins, C.A., Cunningham, P.B., & Pickerel, S.G. (2005). “Predictors of treatment Response for Suicidal Youth Referred for Emergency Psychiatric Hospitalization.” Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 34 (3), pp. 582-589.

- Huff, C.O. (1999). “Source, recency and degree of stress in adolescence and suicide ideation.” Adolescence 34 (133), pp. 81-89.

- Iga, M. (1981). “Suicide of Japanese youth.” Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 11, pp. 17-30.

- Juon, H.S., Nam, J.J. & Ensminger, M.E. (1994). “Epidemiology of suicidal behavior among Korean adolescents.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines 35 (4), pp. 663-676.

- Lelchuk, Irene and Erin Allday (2007). “Parents reflect, schools mobilize to curb suicide: High-achieving teens often don’t exhibit typical warning signs.” SF Gate.

- Ohannessian, C.M., Lerner, R.M., Lerner, J.V., & von Eye, A. (1994). “A longitudinal study of perceived family adjustment and emotional adjustment in early adolescence.” Journal of Early Adolescence 14 (3), pp. 371-390.

- Reinherz, H.Z., Stewart-Berghauer, G., Pakiz, B., Frost, A.K., Moeykens, B.A., & Holmes, W.M. (1989). The relationship of early risk and current mediators to depressive symptomatology in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of child and Adolescent Psychiatry 28, pp. 924-947.

- Rigby, K. & Slee, P. (1999). “Suicidal ideation among adolescent school children, involvement in bully-victim problems, and perceived social support.” Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 29, pp. 119-130.

- Rubenstein, J.L., Heeren, T., Housman, D., Rubin, C. & Stechler, G. (1989). Suicidal behavior in ‘normal’ adolescents: risk and protective factors.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 59 (1) pp. 59-71.

- Shagle, S.C. & Barber, B.K. (1995). “A social-ecological analysis of adolescent suicidal ideation.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 65 (1) pp. 114-124.

- Solomon, D., Battistich, V., Watson, M., & Lewis, C. (2000). “A six-district study of educational change: direct and mediated effects of child development project.” School Psychology of Education 4, pp. 3-51.

- Southam-Gerow, M., Kendall, P.C., & Weersing, V.R. (2001). “Examining outcome variability: Correlates of treatment response in a child and adolescent anxiety clinic.” Journal of Clinical Shild Psychology 30, pp. 422-436.

- Sun, Rachel and Hui, Eadaoin (2007). “Building social support for adolescents with suicidal ideation: implications for school guidance and counselling.” British Journal of guidance and Counselling 35 (3), pp. 299-316.

- Tadeja, M. (2007). “Suicidal, Part Two: Signs the Experts DO NOT KNOW” Gypsy. Web.

- Tomori M., Kienhorst, C.W.M., de Wilde, E.J., & van den Bout, J. (2001). “Suicidal behavior and family factors among Dutch and Slovenian high school students: a comparison.” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 104, pp. 198-203.

- Verkuyten, M., & Thijs, J. (2002). “School satisfaction of elementary school children: the role of performance, peer relations, ethnicity and gender.” Social Indicators Research 59, pp. 203-228

- Weisz, J.R., Weiss, B., Han, S., Granger, D.A., & Morton, T. (1995). “Effects of psychotherapy with children and adolescents revisited: A meta-analysis of treatment outcome studies.” Psychological Bulletin 117, pp. 450-468.

- Zweig, J.M., Phillips, S.D., & lindberg, L.D. (2002). “Predicting adolescent profiles of risk: looking beyond demographics.” Journal of Adolescent Health 31, pp. 343-353.