Abstract

Medical errors caused by a breakdown in communication among hospital employees are one of the leading forms of error in the healthcare industry. The Joint Commission (TJC) found that more than 70% of all sentinel events occurred due to a breakdown in communication among healthcare workers. In 2014 approximately 63% in the first six months had involved handoff miscommunication among health care providers that occurred during transitions of care from one provider to another, which eventually were shown to cause preventable adverse events for their patients (TJC, 2017). A communication tool called Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation (SBAR) has been established to help with improving communication and thus decreasing

incidences of medication errors within hospitals. The project seeks to implement the SBAR communication tool at Crozer Chester Medical Center (CCMC) in the Shock Trauma Unit and to evaluate its effectiveness using the clinical evaluation tool (CEX). Data was collected before and after the implementation of SBAR by observing nurses using the CEX tool and counting the number of medication errors recorded in the event reporting system (ERS). There was a statistically significant difference in the CEX handoff data before the intervention as compared to pre SBAR implementation.

Standardization of an effective handoff process between providers is crucial to help reduce and eliminate the risk of errors during the transfer and continuity of care. This quality improvement project attempted to standardize handoff communication between nursing staff in the STU. Standardized communication during the end-of-shift handoff became a requirement in that year’s National Patient Safety Goals and beyond. Utilization of a standardized hand off communication tool is a publicized practical approach in decreasing communication.

Introduction

On our planet, communication is fundamental to accomplishing something. A lack of communication usually creates disarray, as has always been witnessed in the healthcare sector, and among many other industries as well. Consistency in communication is helpful in encouraging collaboration, thereby reducing, or preventing errors (Rayner & Wadhwa, 2020). The continuing surge of errors has resulted in many U.S. healthcare providers coming together for the purpose of providing coordinated and seamless patient care. Medication errors have been a leading cause of death, and the cost of these errors has exceeded approximately $43 billion worldwide (Padula & Steinberg, 2021).

The situation, background, assessment, and recommendation (SBAR) tool is a technique that many in the healthcare sector have considered helpful in solving handoff communication problems. The technique is effective in bridging the gap witnessed among healthcare practitioners (Abbasi, 2020). The SBAR is a communication briefing model that has proven to be effective in the enhancement of handoff communication (Castelino et al., 2015).

The Shock Trauma Unit (STU) of the CCMC needed further improvement to reduce many of the medical errors that have been reported over the past six months. In some instances, medication errors go without being reported in the system. The purpose of this quality project was to evaluate the impact standardization of Situation, Background, Assessment and Recommendation (SBAR) intervention hand on the incidence of medication errors within a health care setting.

Problem Description

To foster continuity of care and provide safe patient care, the handoff between healthcare providers is one of the critical factors. The handing off of information has been recognized as a vulnerable step that many health practitioners fail to complete effectively. As such, this demonstrates the importance of effective communication when administering treatment. According to the Joint Commission, approximately 1,000 cases of care discontinuity occurred in 2018 due to a lack of proper handoff guidelines. In these cases, communication was the fundamental cause of more than 70% of the severe medical errors reported (Campbell & Dontje, 2019). Medication errors, delays in discharges because of uncertainty in the transfer of patients to critical care, inaccurate patient plans, and repetitive tests, among other factors, have been the consequences of failed communication during the handoff.

The Shock Trauma Unit (STU) of Crozer Chester Medical Center (CCMC) has experienced medication errors in the past. According to the national data and benchmark, the rate is greater than expected in such a small unit. Previously, there have been more than three reported medication errors in one month, and the management of the hospital has sought actions that will mitigate this problem (Hasan et al., 2017).

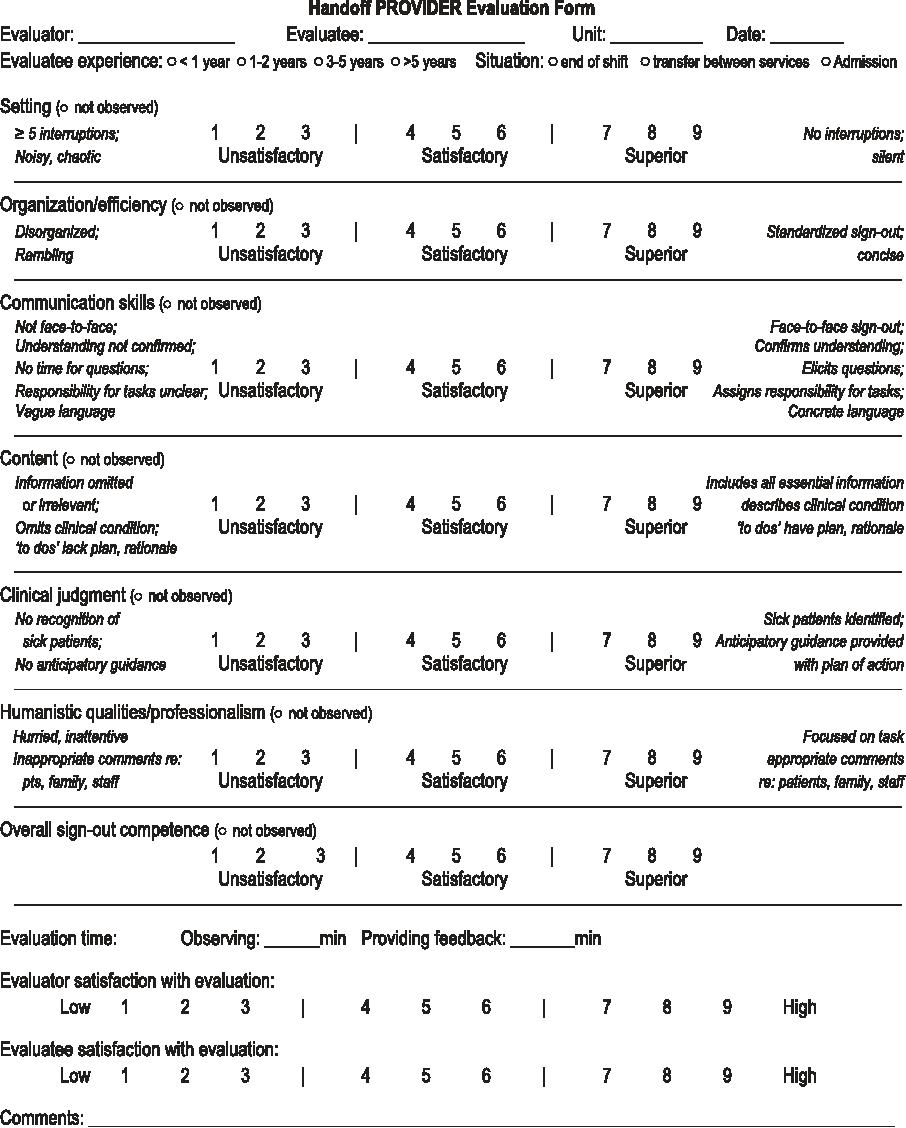

The project focuses on the implementation of SBAR and its evaluation by using the CEX tool on the STU to reduce medication errors. The evaluation will be helpful to the hospital’s management in terms of reducing errors and patient harm associated with handoff communication. The CEX tool consists of six domains and one overall assessment: setting, organization/efficiency, communication skills, content, clinical judgment, patient-focused, and overall sign-out quality. Each domain from the CEX tool was assigned a score from one-nine; one-three was satisfactory, four-six was acceptable, and seven-nine was superior (Hasan et al., 2017). Written permission to utilize the published Handoff CEX was obtained and granted by the tool developer Dr. Horwitz. This tool can effectively provide a clear, concise handoff to all healthcare providers or receiving team members, provide effective communications with all team members, and explore the role transition of the nurse-to-nurse report.

Rationale

Communication competence has been described as “the awareness and appropriate interpretation of the communications patterns in each situation and the aptitude to use the knowledge” (Purtell, Cullinan & Canary, 2019, p. 9). Studies have shown that nearly 100,000 lives are lost yearly in the U.S. due to preventable medical errors (Fleiszer et al., 2015). Medical errors taking place in a STU are often serious, and the cause of many of these numerous errors stems from handoff communication problems (Fleiszer et al., 2015). Studies have also suggested that if healthcare quality is to improve, then communication between the providers of healthcare services must also be enhanced (Fleiszer et al., 2015). There is often a breakdown in communication either during the patient care handoff, when a patient is transferred, or when the individuals responsible for patient care change because of a schedule modification or acuity. Due to these handoff communication problems, the project purpose was to implement and evaluate the effectiveness of SBAR using pre and post CEX implementation scores

The use of warm handoff was shown to improve communication among the staff at the transfer and at the end of the shift (Britton, Hodshon & Chaudhry, 2019). The implementation also highlighted specific barriers to the handoff related to hospital structure and clinician workload (Britton, Hodshon & Chaudhry, 2019). Addressing these underlying matters will be critical in ensuring the continued participation and support for efforts that foster direct communication among clinicians from different institutions (Britton, Hodshon & Chaudhry, 2019).

Picot Question

On the Shock Trauma Unit (P), will the use of a SBAR tool (I) by nurses during nurse handoffs improve communication (C) and decrease the incidence of medication errors and improve CEX scores compared to not using the SBAR tool (O) over a period of six weeks (T)?

Specific Aim

The purpose of this evidence-based practice (EBP) project was to enhance the quality and continuity of patient information that is being transferred during the end-of-shift handoff. The project focused on showing how the implementation of SBAR can be effective in solving problems that have been associated with handoff communication. Reductions of the number of medical errors and the CEX results are the determinants that will be helpful in ascertaining the effectiveness of the technique.

Search Strategy

There are many databases and extensive existing literature that examine preexisting methods to standardizing handoff communication, such as the Academic Search Premier, Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE) with Full Text; Health Source: Nursing Academic; ProQuest Nursing and Allied Health Source; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) complete; and the Cochrane Database of Systemic Review. Inclusion criteria included research studies addressing the PICOT question with a primary focus on high-quality, consistent, and patient-oriented clinical evidence utilized by John Hopkins Nursing. Search limits included the English language and publication dates within the last five years. Inclusion criteria included research studies that directly discussed the proposed theme, with a principal focus on extraordinary quality and reliable clinical evidence appraised with the John Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice: Evidence Level and Quality Guide. Search modes and limitation included the use of full text and scholarly articles written and/or translated in the English language and published within the past five years. Studies were excluded if they had no relevance to the quality project. Finally, references from the selected articles recognized additional studies for review. There were approximately 350 articles reviewed, and the author will use 50 articles for this quality improvement project.

EBP Model

The Evidence Based Practice (EBP) model is a problem-solving approach to the delivery of healthcare that integrates the best clinical evidence into practice. According to the John Hopkins Medicine Center for EBP model, the “JHNEBP model is a powerful problem-solving approach to clinical decision-making and is accompanied by user-friendly tools to guide individual or group use” (Dingle, 2019, p. 9). The literature distinguishes EBP as a process involving the examination and application of study findings or other reliable evidence that have been integrated with scientific theories in which nurses participate in order to make communication better (Dingle, 2019).

Available Knowledge

A variety of themes emerged during the literature review, including quality improvements, reduction of mortality and morbidity, improvement of efficiency, improvement of patient outcome, communication outcome, handoff, patient safety, and the application of SBAR in patient handoff. These themes will be explored in the sections below.

Quality Improvements

Communication between employees affects the provision of medical services and the quality of the hospital as a whole, but this facet of operations is often neglected. When transferring a patient from one medical professional to another, communication shortcomings can take different forms, including the transmission of incomplete information necessary for quality treatment, incorrect information, and incorrect perception of information (Fryman et al., 2017). Confirmation of the importance of improving the communication of medical staff is confirmed by the fact that their mistakes can directly affect the treatment of patients (Bjarnadottir et al., 2018). As a result of Funk et al.’s research, it was found that improving communication between employees contributes to improving the quality of services in medical institutions. Moreover, special tools have been created for doing so, such as SBAR, by using the CEX tool.

Funk et al. (2016) evaluated the significance of structured handovers in clinical care units through surveys of pre-quality and post-quality improvement approaches. The study affirmed that a structured handover worksheet facilitates satisfaction among healthcare providers and improves the communication of information during the handover (Dingle, 2019).

Various tools have been developed to improve the efficacy of bedside handoffs. Campbell and Dontje (2019) carried out a study to design, enact, and assess bedside handoffs’ effects on nursing shift changes in medical facilities’ emergency rooms. Since the health outcomes in emergency departments can be adversely affected by medical errors in unplanned handoff procedures, the study was aimed at developing a project to improve these practices (Campbell & Dontje, 2019). The researchers developed the situation, background, assessment, and recommendation (SBAR) tool to be used in communication during nurse handoffs.

Reduction of Mortality and Morbidity

As a result of the research, it was found out that misunderstandings between medical staff can adversely affect patients, leading to medical errors and even deaths. Consequently, numerous surveys and questionnaires of employees were conducted. Due to the importance of this problem, the U.S. Department of Defense has decided to introduce specific tools in order to improve communication and avoid medical errors (Padula & Steinberg, 2021). As a result, hospital staff have changed their attitude to this problem and have improved communication and the transfer of information.

Medical and surgical errors resulting from communication breakdowns during the transfer of care of patients are the major cause of deaths annually. Despite the requirements and recommendations previously discussed, many healthcare workers report having no systematic process for the handoff of care of patients (Canale, 2018). The Joint Commission and the U.S. Department of Defense Patient Safety Program (DoD PSP) were achieved through the implementation of a standardized handoff procedure communication in order to improve health outcomes (Canale, 2018). In particular, this study was geared towards implementing a standardized handoff in order to facilitate the continuity and quality of medical workers’ satisfaction, patients’ safety perceptions, and information transfer. In numerous healthcare systems, communication errors during handoffs have led to perioperative mortality and morbidity (Dingle, 2019). Poor communication accounts for more than 80% of medical errors (Canale, 2018). The study established how the quick and informal patient transfer by anesthesia provider’s increases miscommunication and error risks.

The study’s methodology involved selecting 20 Certified Registered Nurse Anesthesia (CRNAs) participants through a snowball sampling to generate Team Strategies to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (TeamSTEPPS) (Canale, 2018). After completing a post-intervention questionnaire, the results indicated that the TeamSTEPPS improved the continuity and quality of the healthcare workers’ satisfaction, patient safety perceptions, and information transfers.

Improvement of Efficacy

After introducing the SBAR tool to improve communication between employees, a study was conducted in order to calculate the improvements in the quantitative ratio (Li, et al., 2019). Moreover, it has been found that an enhanced communication strategy can save both resources and time (Blake, 2019). In addition to the introduction of special programs and tools, it was found during the work that staff in the STU also help to facilitate the work of hospital staff.

In recent times, one important handoff tool has been the Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation (SBAR). Castelino and Latha (2015) investigated the importance of the SBAR tool in improving the efficacy of nurse handoffs. To achieve the study’s objective, the researchers assessed 72 handoff events carried out by 72 nurses in both control and experimental groups and collected data via practice checklists, structured questionnaires, and demographic preforms.

The results indicated that the after-test knowledge scores rose from 3.47 to 7.72 following the implementation of the SBAR tools, indicating their effectiveness in improving handoff efficacy. There have been split opinions about the efficacy of minimized but precise handoff frameworks versus the specific formal types. Clanton et al. (2018) compared the impacts of underestimated but precise handoff strategies to a comprehensive standard handoff framework on patients’ health outcomes. Numerous healthcare facilities focus immense amounts of resources and time on handling patient handoffs.

The methodology involved stratifying the two experimental groups composed of 5,157 distinct patient-admissions. The study established the fact that there was no significant difference in the health outcomes of the two groups. However, the study found that a minimalistic handoff strategy can save both resources and time without adversely affecting patients’ health outcomes.

The efficacy of trainee handoffs has also drawn widespread attention in the healthcare community. Clanton et al. (2018) assessed the trainee experience, effectiveness, and utility related to the enactment of original, electronic, and standard handoff approaches. The study carried out a potential intervention assessment of trainee handoffs of sick persons going through intense oncology procedures. The research team assessed the pre-implementation data by tracking delinquencies, direct observation, and trainee surveys. The standardized electronic handoff equipment was designed in a REDCAP database and augmented via face-to-face interactions or direct communication. The statistical analyses were used in assessing the trainee workflow, communication errors, and handoff compliance during post-implementation.

The study results indicate that standardized electronic equipment integrated with uninterrupted communication for patients with high acuity can raise the efficiency, accuracy, and observation of trainee-to-trainee handoff communication.

In order to develop training recommendations for clinical handovers, some studies evaluated past literature. Clarke (2018) conducted a literature review to ascertain the history of healthcare handovers and their efficacy from surgical rooms to post-anesthesia care units (PACU) over the past decade. The assessed literature included in the review was categorized into primary research, theoretical, practice, and policy framework. The study also established that either information transferred in a handover is unclearly manifested or incomplete, or that medical personnel perceive a clinical handover as inconsistent, unstructured, and informal. The study concluded that there is a necessity to enacting educational and training measures that facilitate positive outcomes in a clinical handover, especially in a manner that promotes collaboration (Clark, 2018).

The SBAR tool influences decision-making initiatives in healthcare. Etemadifar (2020) investigated the impact of the SBAR-reliant patient safety emancipation initiative on clinical decisions in ICUs. The study involved a quasi-experiment carried out on 60 ICU nurses in Hajar and Ayatollah hospitals in 1998. The participants were randomly allocated to control and experimental groups of 30. The results indicated that the experimental ICU nurse group’s clinical decision-making efficacy improved from 69.1 to 80.8 after the intervention. In contrast, the scores of the control group improved only from 70.6 to 71.1 after the intervention. The research affirmed that implementing the SBAR strategy in nurse education programs improved their decision-making efficacy.

Improvement of Patient Outcomes

Maintaining clear and understandable verbal communication is essential to improving patient outcomes. The study found that SBAR is vital to facilitating the transfer of authority in the health sector (Liu et al., 2018). The results show that the integration of SBAR in medical institutions facilitates the assessment of knowledge on job satisfaction, communication, and functional relationships (Müller et al., 2018). In the course of the study, it was found that the inclusion of SBAR modeling with patient data transmission improves DNP student’s collaboration, communication, and information exchange, thereby contributing to positive outcomes for the patients.

Upholding clear and comprehensible verbal communication is essential for improving patient outcomes. Daniels et al. (2017) investigated opportunities for facilitating effective communication in labor and delivery rooms through simulations. The study assessed the prevalent verbal communication barriers in labor and delivery rooms, as well as effective strategies for eradicating these obstacles. According to Daniels et al. (2017), communication errors are critical proponents of adverse health results in the labor and delivery units (L&D). In the research study, medical practitioners in L&D units took part in three simulated clinical situations which were recorded and analyzed in order to locate repeated questions. The repetition frequency was also evaluated, and the results indicated that questions were repeated in 27 cases and were mainly concentrated on personnel, maternal clinical status, and historical data.

The SBAR Is vital in facilitating handoff procedures in healthcare. Dalky et al. (2020) evaluated the significance of SBAR in reducing handoff procedures in healthcare. The SBAR refers to a standardized handover instrument that is primarily utilized in nursing practice (Dalky et al., 2020) and facilitates positive outcomes in both healthcare quality and staff communication. The study aimed to assess SBAR implementation among nurses in Jordan’s ICUs.

The research evaluated 71 ICU nurses through a 43-item questionnaire (Dalky et al., 2020). The questionnaire assessed SBAR efficacy marked by job satisfaction levels, leadership, team communication, and general relationships. The results indicate that integrating SBAR in healthcare settings facilitates higher knowledge scores in job satisfaction, communication, and functional relationships.

Conover et al. (2020) investigated the effectiveness of the simulations of SBAR and patient handoffs for nursing students who have not yet acquired practice licenses. The study established the fact that including SBAR simulations with patient handoffs improves the students’ collaboration, communication, and information exchange, thereby facilitating positive patient outcomes.

Communication Outcomes

Communication is very crucial in nursing, where interventions such as treatment, rehabilitation, health promotion, prevention, education, and therapy communication play critical roles. Poor communication in healthcare facilities during handovers has been identified as a fundamental cause of medical errors (Ramasubbu, Stewart & Spiritoso, 2017). A 2016 study carried out on 10 hospitals found that receivers determined 37% of their handovers to be unsuccessful, while 21% of the handovers were unsuccessful for the senders. Another study exploring how miscommunication among healthcare providers can affect the safety of patients indicated that providers are consistently less likely to verbalize misconduct about the care provided by co-workers (Johnson et al., 2020).

More than 1,700 healthcare providers were surveyed about communication gaps that could impact a patient’s safety (Johnson, Carrington & Rainbow, 2020). The study found that approximately 10% of the healthcare providers directly confronted their colleagues about their concerns, and only one in five said that they have had seen harm come to patients due to handoff failures. Another recent study assessed the prevalence and characteristics of handoff incidents in hospitals and found unsatisfying results.

The review focused on handoff incidents that occurred over three years and found that 334 handoff incidents, such as administering the wrong medication or forgetting to give a patient medicine at a specific time, took place within the timeframe (Halt, 2020). The main reasons why these handoff incidents happened were because of a poor handoff and/or the absence of any handoff program.

Incorporating practical handoff tools in nursing units can help reduce medical errors. Deal (2020) carried out a study to integrate the ISHAPED handoff instrument into an operational nursing unit and to validate past handoff communication research. The study focused on filling gaps in the strategies for improving nurse-to-nurse communication during handoff processes. The study also evaluated how TeamSTEPPS communication initiatives help to facilitate job satisfaction among nurses communicating during shifts, as compared to present practices (Keating, McLeod-Sordjan & Lemp, 2021).

A shift report assessment was carried out for pre- and post-implementation data about the nurses’ ideologies about handoff communication. The study’s results indicate that using the TeamSTEPPS strategy to implement a bedside shift facilitated greater collaboration between patients and nurses (Deal, 2020). Integrating the ISHAPED handoff tool with the bedside shift report also enabled nurses to become more effective in caring for their patients due to thorough, high-quality, and consistent handoff information. The integration also facilitated efficient communication between night and day shift nurses, thus limiting healthcare-related errors (Deal, 2020). The goal is to always include patients in the ISHAPED nursing shift-to-shift handoff process at the bedside in order to avoid medical and medication errors and adding the additional layer of safety by allowing the patient to interconnect possible safety concerns (Deal, 2020).

The strength of effective handover processes lies primarily in communication efficacy. Miscommunication between nurses when carrying out patients is the main cause of medication errors (Streeter, 2017). Handoffs result in approximately 80% of grave medical care errors (Streeter, 2017). The qualitative research located distinct communication practices related to effective patient handoffs during a shift change. The research team gathered data from 286 nurse practitioners via online questionnaires, and the study’s results affirm that socio-emotional communication behaviors and information exchange practices, such as seeking, providing, and verifying information, are dominant in the best nursing handoffs.

Due to a greater diversity in the clinical setting, language barriers do exist, but these can be facilitated through bilingual training. (Pun, 2020) investigated practical training programs for handovers in bilingual health-care facilities. Accountability is vital in promoting higher quality during handovers because the design of handovers necessitates a systematic assessment of nurses’ actions (Esaka, 2020). The study also included administering a training program that was reliant on the CARE protocol to 50 nurses, followed by evaluating their practices and perceptions. The study results indicate that the training programs need to conform to an organized handover framework, promote effective communication with incoming nurses, and promote the perfection of transfer of functions by the outgoing medical practitioners.

Tracking documented and undocumented information can help to reduce medical errors. Patterson et al. (2019) aimed to identify the role of non-documentation communication in nursing handovers, the location of documented information, and the data content that was present in verbal reports. Translating approved handover reports from nurses in non-emergency scenarios to nurses in critical methods is a difficult task (Patterson et al., 2019).

This research study evaluated 20 reports on 27 patients from two different ICUs. The study established the fact that handover information is primarily documented in previous medical history, orders, lab results, nurse flowsheets, and administration records. The results indicate that typically undocumented information involves mentorship, coordination work, sharing clinical interpretations, and offering patient-focused services.

Effective communication, teamwork, and accountability each improve the success of patient handoffs. Lee et al. (2019) investigated how various aspects of patient safety culture relate to patient safety perceptions and clinical handoffs. The study assessed the statistical connections between transition practices and handoffs, patient safety, and patient safety culture. The study results indicate that appropriate accountability, responsibility, and correct information during a handoff are essential in facilitating positive patient safety perceptions (Noh & Lee, 2018). Communication and feedback on medical errors were positively attributed to the effective transfer of patient information. Finally, the frequency of events and teamwork in clinical units were positively associated with an effective handoff of responsibilities when swapping shifts (Hasan et al., 2017).

The introduction of practical transfer tools in nursing departments has helped to reduce the number and frequency of medical errors. The study results show that the use of the TeamSTEPPS strategy to implement a bedside shift facilitated greater collaboration between patients and nurses (Streeter & Harrington, 2017). Integration also facilitated effective communication between night and day shift nurses, thereby limiting errors related to the provision of medical care. Thus, effective communication, teamwork, and accountability each help to increase the effectiveness of the patient transfer.

Handoff

Based on various findings, the study identified the ways in which transmissions occurring in high-impact settings could be replicated in the healthcare sector in order to improve patient safety (Francis, 2020). During the investigation, it became clear that researchers had observed the transfer process before introducing a standardized transfer worksheet. Thus, the transfer worksheet had to be redesigned considering the needs of the staff. Based on the literature review, educational and training measures aimed at cooperation have been shown to be necessary in order to promote positive results in transmission (Uhm, Ko & Kim, 2019). That is why communication is a cause of adverse health consequences in respective departments, leading to approximately 80% of serious medical errors.

A handoff refers to the transfer and acceptance of responsibility of caring for a patient, and this is achieved through effective communication (Hee at al., 2019). The handoff process usually occurs in real-time, during which a caregiver communicates information about the patient to another caregiver in order to ensure the patient’s continued care (The Joint Commission, 2017). The handoff is an essential aspect of patient care, and thus there is a need to improve it.

The handoff process is very crucial in a variety of settings. The number of medical errors that have been witnessed over time due to miscommunication has led several health-care institutions to conduct a concise handover process with essential information about every step (Patterson et al., 2019).

Observational data were collected for evidence of 21 handoff strategies. Based on the various findings, the study concluded that handoffs occurring in high-consequence settings could be replicated in the healthcare sector in order to improve patient safety (Allen, 2016). Since the survey conducted a similarity examination of the handoffs between four locations, the study failed to explore each strategy’s effectiveness as observed in the different settings and how they could be effective in the healthcare sector.

A study aiming to standardize handoffs and thus to improve patients’ safety and reduce end-of-shift overtime was conducted within four years. The study incorporated the use of the continuous performance improvement (CPI) methodology (Bereskie et al., 2017).

Continuous performance improvement is a methodology that is vital in facilitating the improvement of work methods, improving quality outcomes, standardizing work, and identifying waste (Smith, et al., 2018). Before the implementation of the standardized handoff worksheet, the researchers observed the handover process. The handoff worksheet thus had to be redesigned in order to accommodate the needs of the staff (Bereskie et al., 2017).

After the redesign, the standardized worksheet was implemented and data from the handoff process were collected. Incorporating the use of the continuous performance improvement (CPI) methodology is recommended (Bereskie et al., 2017).

The handoff worksheet had to be redesigned in order to accommodate the needs of the staff. After the redesign, the standardized worksheet was implemented and data from the handoff process were collected. Within a week of the implementation, 87% of the staff were following the standardized method, with 70% of the staff completing the handoff process within 30 minutes (Bereskie et al., 2017). The end of shift overtime was reduced, and the data collected indicated sustained improvements in safety checks as well.

The efficacy of trainee handoffs in healthcare has drawn widespread attention. Clarke et al. (2019) established the fact that standardized electronic equipment integrated with uninterrupted communication for patients with high acuity could raise the efficiency, accuracy, and observation of trainee-to-trainee handoffs. Through a literature review, Clarke (2019) concluded that there is a necessity to enact educational and training measures that focus on collaboration in order to facilitate positive outcomes in the handover. Pun et al. (2020) found that training programs must conform to an organized handover framework, promote effective communication with incoming nurses, and perfect the transfer of functions by outgoing medical practitioners.

The strength of effective handover processes lies in communication efficacy. According to Daniels et al. (2017), communication errors are proponents of adverse health outcomes in labor and delivery units, resulting in approximately 80% of serious medical errors. Streeter et al. (2017) affirmed that socio-emotional communication behaviors and information exchange practices such as seeking, providing, and verifying information were dominant in the best nursing handoffs. Patterson et al. (2019) found that handover information is primarily documented in previous medical history, orders, lab results, flowsheets, and administration records, while mentorship, coordination work, clinical interpretations, and patient-focused services have been forgotten. Lee et al. (2016) conducted a study and presented results that indicate that appropriate accountability, responsibility, and information handoff are essential in facilitating positive patient safety perceptions. In addition, communication and feedback on medical errors were positively attributed to the effective transfer of patient information.

Patient Safety

The Joint Commission has recognized that medication errors have been one of the top ten events affected by ineffective handoff communication trials (Canale, 2018). The author claims that ensuring patient safety is one of the most important goals of the healthcare sector (Abbasi, 2020). Paying careful attention to the phenomenon of professional communication skills can reduce the number of critical medical errors that take place. The author discusses the importance of implementing the SBAR by using the CEX tool, which has qualitatively improved the culture of patient safety and the responsibility of nursing staff. This study helped the authors of this work, as it contains results proving that the SBAR communication model is an effective means of improving safety culture. Hasan et al., in their article “Evaluating handoffs in the context of a communication framework” (2017, p. 27), write that the transfer of patient care services leads to increased opportunities for errors during this process. The authors of the article conducted a study that evaluated the process of transferring patients in the context of a specific communication system. This study identified assessment tools for the source, recipient, and observer to identify factors that might be affecting the transmission process.

The success of handoff communication in the clinical setting determines patients’ safety. Birmingham et al. (2015) carried out a qualitative study to assess surgical nurses’ perspectives regarding the processes that inhibit or facilitate patient safety during handoff and intra-shifts. According to Birmingham et al. (2015), viable handoff communication is essential to ensuring patient safety. In particular, the communication strategies implemented during intra-shift processes also influence the effectiveness of handoff procedures (Harris-Hines, 2020).

The study established that nurses’ outgoing capability in comprehending information intra-shift is vital for depicting the comprehensive health situation during handoffs and enabling smooth transitions. Furthermore, when incoming nurses understand the information conveyed during a handoff, all practitioners collectively understand each other, thus minimizing medical errors and facilitating patient safety (Harris-Hines, 2020). The demand for quality medical services has continued to grow globally, and has also surpassed the costs associated with them. Deloitte Global reported that 12.6% of the total global domestic product (GDP) is spent on healthcare (Melvey & Slovensky, 2017).

The study estimated that the share is expected to rise by 3.6% and reach around nine billion U.S. dollars by 2020. But even with these massive investments in the healthcare industry, a wide variety of studies have suggested that patient safety has not been adequately addressed (Ellis & Abbott, 2018). As such, this is a hot topic during all these various developments.

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada (ISMPC) advises healthcare facilities to accord the highest priority to patient safety (Hee et al., 2019). Any slight negligence in providing necessary attention can erode consumers’ trust in healthcare, thereby escalating medical costs, among many other unforeseen circumstances. The institute also advises healthcare facilities to accord the highest priority to patient safety (Hee et al., 2019). A patient’s life may be at risk due to medical errors that may arise from different quotas. Handoff communication is one of these quotas upon which medical errors can occur (Abbasi, 2020).

Nurses are always charged with the responsibility of providing care to patients (Bukoh & Siah, 2020). As such, it is thus always logical that as one ends his or her shift, he or she must brief colleagues on anything concerning the patient in order to be well conversant with what might be required in case anything happens.

Application of SBAR in Patient Handoff

Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation (SBAR) has consistently demonstrated its effectiveness in improving communication in various settings (Muller et al., 2018). The U.S. Navy developed SBAR to help with the standardization of critical and urgent communications in nuclear submarines (Jeong & Kim, 2020). SBAR’s use in the Navy setting was so significant that it gained a wide audience in the non-military environment as well (Nagammal et al., 2016). The implementation of SBAR in the healthcare environment was first achieved at Kaiser Permanente, Colorado (Allen, 2016). Since then, the technique has become synonymous with successful communication in the sector. Many organizations have found it to be a valuable method since its format captures crucial information and streamlines communication and is also valid for all sorts of inter-staff interactions as well (Achrekar et al., 2016). SBAR serves as a helpful tool that standardizes communication, enhances provider empowerment, and promotes patient ownership (Shahid & Thomas, 2018). This wide range of the available uses of SBAR has given the technique significant prominence in the healthcare sector, as well as other sectors such as transportation.

Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation (SBAR) is the chosen tool because it provides an excellent framework for communication. The system serves as an empowerment tool that offers opportunities to ask all kinds of questions, ensure that the relied information is understood, and formulate a care plan (Kilic et al., 2017). Handoff involves exchanging information and transferring responsibility and accountability and is also an excellent teaching opportunity.

The success of handoff communication in the clinical setting determines patient safety. Birmingham et al. (2015) conducted a qualitative study that established that viable handoff communication is essential. The study shows that the outgoing and incoming nurses’ capabilities to comprehend information intra-shift is vital for depicting the health situation during the handoff, minimizing medical errors, and enhancing patient safety. Bukoh et al. (2020) found that a standardized and structured handover such as SBAR reduces mortality rates, minimizes hospital stay, suppresses fall rates, and enhances emergency responses. The study outcomes also ascertained that structured handover frameworks mitigate hard handovers in order to avoid documentation challenges, information inaccuracy, and data omission (Bukoh et al., 2020; Harris-Hines, 2020). Funk et al. (2016) affirmed that a structured handover worksheet like SBAR facilitates patient satisfaction and improves communication during the handover.

Various tools have been developed to improve the efficacy of bedside handoff. Campbell and Dontje (2019) created the SBAR tool utilized in handoff communication in order to reduce missing patient data that might be present in pre-intervention practices. Castelino and Latha (2015) found that SBAR improved after-test knowledge scores from 3.47 to 7.72. Dalky et al. (2020) showed that integrating SBAR in healthcare settings facilitates knowledge scores in job satisfaction, communication, and general relationships. Conover et al. (2020) also confirmed that including SBAR simulations with patient handoff improves student collaboration, communication, and information exchange, thus facilitating positive patient outcomes. Etemadifar’s (2020) findings indicate that an experimental ICU nurse group’s clinical decision-making efficacy improved from 69.1 to 80.8 after SBAR intervention. Contrastingly, the control group’s scores only improved from 70.6 to 71.1 after the intervention, thus affirming that implementing the SBAR strategy in nurse education programs improves their decision-making efficacy.

Canale (2018) developed standardized handoffs for sedated patients in order to facilitate the continuity and quality of medical workers’ satisfaction, patient safety perceptions, and information transfer. Handoff communication errors lead to perioperative mortality and morbidity and account for over 80% of medical errors (Dingle, 2019; Canale, 2018). While Clanton et al. (2016) found no significant difference in health outcomes between minimized yet precise handoff frameworks and specific formal types, a minimalistic handoff strategy can save resources without adversely affecting health outcomes. Deal’s (2020) study results indicate that utilizing the TeamSTEPPS strategy to implement bedside shift facilitated greater collaboration between patients and nurses.

Integrating the SHAPED handoff tool with the bedside shift report enabled nurses to become more effective in caring for their patients due to thorough, high-quality, and consistent handoff information (Esaka, 2020). The integration also facilitated efficient communication between night- and day-shift nurses, thus minimizing healthcare-related errors.

Use of the CEX Tool

The standardized tool known as the CEX was developed based on the mini-CEX. The tool consisted of seven domains scored on a 1-9 scale (Kurdi & Hungund, 2021). Nursing educators observed shift-to-shift handoff reports among nurses and evaluated both the provider and recipient of the report. Nurses participating in the report also simultaneously evaluated each other as part of their handoff (Horwitz, et al, 2013). The situation, background, assessment, and recommendation (SBAR) tool is considered to be one of the ways in which handoff communication problems can be solved while also helping to improve healthcare services (Jasemi, Ahangarzadeh, Hemmati & Parizad, 2019). Handoff reports have often been shown to improve communication during the shift report (Britton, Hodshon & Chaudry, 2019).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the literature review reveals the importance of the handoff process in safeguarding patient safety (Lloyd, D’Errico & Bristol, 2016). The existing literature reveals critical information concerning the benefits of implementing a standardized SBAR tool for the handoff process. Since several studies focus on physician and nurse handoffs, much analysis is still needed regarding nurse-to-nurse handoffs and how they can be affected using the SBAR technique. As such, the project was focused on implementing SBAR to improve nurse-to-nurse handoff communications.

Methodology

Context

The Crozer Chester Medical Center, which is the largest employer in Delaware County, PA, provides a friendly work environment that promotes professional growth and also provides enrichment opportunities for its employees. The healthcare institution is in Chester, Pennsylvania, and is based on an academic health system that drives medical advances through clinical innovations, pioneering research, and world-class education (Hernandez, 2020). This organization has an ethical and professional responsibility to offer the best and highest-quality patient care. The emergency department of this institution serves over 40,000 patients annually, and the institution has over 300 licensed beds. The Crozer Chester Medical Center (CCMC) is a teaching facility well-known for producing gifted teachers and innovative researchers. The CCMC is proud to offer over 30 specialties and provides varying complexities that serve over a million patients each year (Nuuyoma & Makhene, 2020). The patient care code provides high-level guidance regarding every employee’s expectation for collaborative work, financial record maintenance, and quality in all healthcare systems for ongoing and comprehensive feedback from stakeholders. This quality improvement project will be completed as a voluntary commitment of the DNP candidate.

The DNP quality improvement project occurred in the Shock Trauma unit, which has eight beds. The nursing staff in the department participated in the quality improvement initiative because this opportunity took place within their working hours. There are 20 nursing staff who work full-time on this unit, as well as another 10 registered nurses who work whenever there is a staffing need. The length of patient stay in this unit is approximately 4-10 days. These patients are critically ill and have numerous co-morbidities.

Study of Intervention

This quality project identified and measured a clinical safety problem related to handoff communication in patients directly admitted to the STU. The evidence-based quality improvement initiative occurred over three steps. The first step took place prior to the implementation of the SBAR framework. During this step, preexisting handoff practices were observed and documented using the CEX tool over a six-week period. The number of reported medication errors was also collected during this step. In the second step, the DNP candidate provided the staff with a 30-minute in-service education session about the use of the SBAR tool during shift handoffs. The DNP leader provided time to discuss scenarios to demonstrate the SBAR framework in practice, to ask questions, and to assess the nursing staff’s general level of understanding.

During the third and final step of the project, the DNP student observed the STU nursing staff performing an end-of-shift handoff using the SBAR tool. Once again, the CEX tool was used to document the process. In addition, the number of reported medication errors was collected during this step over a six-week period.

Data Analysis Procedures

The clinical question in this project aimed to understand the impact of the SBAR tool intervention on the quality of nurse-to-nurse shift handoff communication and on the frequency of medication errors using a 30-day pretest-posttest design (Kacena, 2020).

A paired t-test was completed as the project examined the independent factor (SBAR) among nursing participants and its impact on the frequency of medication errors, as well as pre- and post-SBAR implementation CEX tool results.

The mean value of the dependent variable for pre- and post-test scores were obtained, along with the standard deviation and standard error. The p-value is also presented. If the p-value is less than.05, then we can conclude that there is a statistically significant difference. If the p-value is greater than.05, it can imply that there is no statistically significant difference (Ross & Wilson, 2017). The project’s design also evaluated the same group and examined the handoff pre- and post-SBAR implementation using the CEX tool (Cullen et al., 2017). The DNP project leader was able to evaluate the communications among staff during the end-of-shift report and compare the different years of clinical experience and level of the education of the nurses involved. The results evaluated the same cohort and examined the handoff pre- and post-SBAR implementation during all shifts (day, evening, and night).

Budget

This project was completed via the voluntary commitment of the DNP student’s time. There were no expenses or income associated with this project. The intervention was integrated into daily routines, and the process of improving handoff communication among the nursing staff on the Shock Trauma unit did not require a formal budget outside of the unit’s operating budget because it was conducted during the staff’s working hours.

Ethical Consideration

Approval for this evidence-based quality project was obtained from the clinical director of the Shock Trauma Unit, as well as Wilmington University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). All project data will be maintained in a secured and locked location within the facility. The DNP project leader will be the only person who can access the key to the locked filing cabinet where the documents will be stored, and all electronic documentation will be kept in a password-protected file. This quality project does not involve any video or audio recording during the data collection process.

Results

Participants

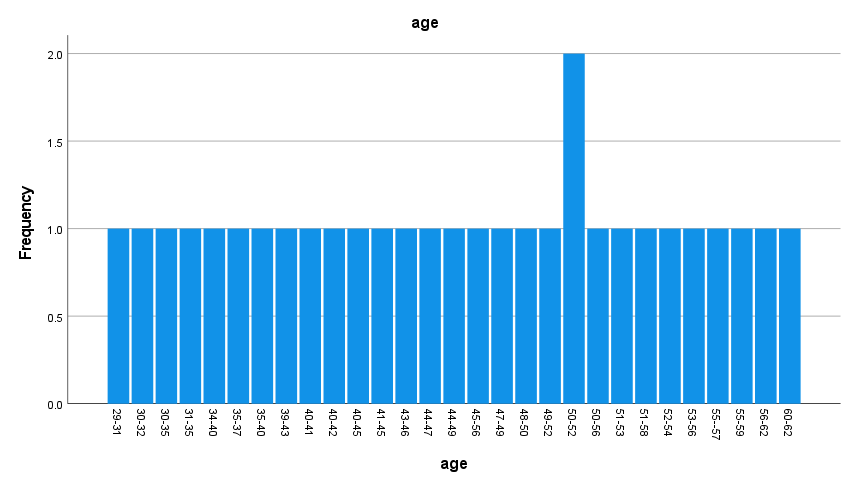

There were 30 participants in the study, and 150 handoffs were observed (20 for the 3-11 morning shift, 70 for days from 7a-7p, and 60 for the night shift from 7p-7a). There were four male participants (13.3%) and 26 female participants (86.7%). There were 14 European Americans (46.7%) and eight African Americans (26.7%), with three Hispanics (10%) and five other races (16.7%). Twenty-seven participants had a BSN (90%) while one participant had a diploma (3.3%), and two participants were master’s degree prepared (6.7%). There were two participants between 50 and 52 years old (6.7%).

The nursing population in the United States includes a makeup of 10.2% Hispanic or Latino; 7.8% Black or African American; 5.2% Asian;.7% two or more races; 0.6% Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander; and 0.3% American Indian or Alaskan Native.

There are more than 9% male nurses in the United States (Carson-Newman University, 2021). Forty-one and seven-tenths of nurses in the United States have a BSN (Vaishnavi & Kuechler, 2021).

The percentage of men in the study is larger than the national average. The percentage of European Americans in the study is higher than the national average. The percentage of nurses with a BSN is larger than national averages.

Table 1a: Frequency Distribution – Gender and Race

Table 1b: Frequency Distribution –Age

Results

A paired-samples t-test was performed to examine the PICOT question. The paired samples t-test is most appropriate for determining the mean value of the dependent variable for pre- and post-test scores. Thus, the paired samples t-test is most suitable for examining whether using the SBAR tool by nurses during the nurse handoff improves communication and decreases the incidence of medication errors compared to not using the SBAR tool over a period of six weeks. Missing data were replaced with zeros. The results of pre- and post-CEX tool scores are presented below. Individual CEX tool category scores will be presented in the following sections.

Setting

The results are presented for pre- and post-setting. Pre-setting CEX scores had a mean of 6.23 and a standard deviation of 1.00. Post-setting CEX scores had a mean of 8.57 and a standard deviation of 0.50. There was a statistically significant improvement in CEX scores using the SBAR tool from 6.23 ± 1.10 m to 8.57 ± 0.50 m (t (29) =-11.06, p<.05, 95% CI, -2.76, -1.90). Thus, the use of the SBAR tool by nurses during the nurse handoff improved setting CEX tool scores compared to not using the SBAR tool over a period of six weeks.

Table 2: Paired Samples Statistics

Organization/Efficiency

The results are presented for pre-organization/efficiency and post-organization/efficiency CEX tool scores. Pre-organization/efficiency has a mean of 5.77 and a standard deviation of 0.97, while post-organization/efficiency has a mean of 8.60 and a standard deviation of 0.56. There was a statistically significant improvement in organization/efficiency following the use of the SBAR tool from 5.77 ± 0.97 to 8.60 ± 0.56 (t (29) =-14.73, p<.05, 95% CI, -3.22, -2.44). Thus, the use of the SBAR tool by nurses during the nurse handoff improved organization/efficiency CEX scores compared to not using the SBAR tool over a period of six weeks.

Table 3: Paired Samples Statistics

Communication Skills

The results are presented for pre-communication skills and post-communication skills CEX tool scores. Pre-communication skills have a mean of 6.43 and a standard deviation of 0.77, while post-communication skills have a mean of 8.53 and a standard deviation of 0.57. There was a statistically significant improvement in communication skills following using the SBAR tool from 6.43 ± 0.77 to 8.53 ± 0.57 (t (29) =-11.98, p<.05, 95% CI, -2.45, -1.74). Thus, the use of the SBAR tool by nurses during the nurse handoff improved communication skills CEX tool scores compared to not using the SBAR tool over a period of six weeks.

Table 4: Paired Samples Statistics

Content

The results are presented for pre-content and post-content CEX tool scores. Pre-content has a mean of 5.70 and a standard deviation of 1.17, while post-content has a mean of 8.60 and a standard deviation of 0.56. There was a statistically significant improvement in content CEX tool scores following the use of the SBAR tool from 5.70 ± 1.17 to 8.60 ± 0.56 (t (29) =-14.12, p<.05, 95% CI, -3.32, -2.48). Thus, the use of the SBAR tool by nurses during the nurse handoff improved content CEX tool scores compared to not using the SBAR tool over a period of six weeks.

Table 5: Paired Samples Statistics

Clinical Judgment

The results are presented for pre-clinical judgment and post-clinical judgment CEX tool scores. Pre-clinical judgment has a mean of 5.67 and a standard deviation of 0.66, while post-clinical judgment has a mean of 8.77 and a standard deviation of 0.43. There was a statistically significant improvement in clinical judgment scores following the use of the SBAR tool from 5.67 ± 0.66 to 8.77 ± 0.43 (t (29) =-22.37, p<.05, 95% CI, -3.38, -2.81). Thus, the use of the SBAR tool by nurses during nurse handoff improved clinical judgment CEX tool scores compared to not using the SBAR tool over a period of six weeks.

Table 6: Paired Samples Statistics

Humanistic Quality/Professionalism

The results are presented for pre-humanistic quality/professionalism and post- humanistic quality/professionalism CEX tool scores. Pre-humanistic quality/professionalism has a mean of 6.80 and a standard deviation of 1.21, while post-humanistic quality/professionalism has a mean of 8.73 and a standard deviation of 0.45. There was a statistically significant improvement in humanistic qualities/professionalism following the use of the SBAR tool from 6.80 ± 1.21 to 8.73 ± 0.45 (t (29) =-8.42, p<.05, 95% CI, -2.40, -1.46). Thus, the use of the SBAR tool by nurses during the nurse handoff improved humanistic qualities/professionalism CEX scores compared to not using the SBAR tool over a period of six weeks.

Table 7: Paired Samples Statistics

Overall Sign-out Competence

The results are presented for pre-overall sign-out competence and post-overall sign-out competence CEX tool scores. Pre-overall sign-out competence has a mean of 6.73 and a standard deviation of 0.74, while post-overall sign-out competence has a mean of 8.73 and a standard deviation of 0.45. There was a statistically significant improvement in overall sign-out competence following the use of the SBAR tool from 6.73 ± 0.74 to 8.73 ± 0.45 (t (29) =-14.78, p<.05, 95% CI, -2.27, -1.72). Thus, the use of the SBAR tool by nurses during the nurse handoff improved overall sign-out competence CEX scores compared to not using the SBAR tool over a period of six weeks.

Table 8: Paired Samples Statistics

Medication Errors

The results are presented for pre-medication errors and post-medication errors. Before using the SBAR tool, there were three pre-medication errors. After using the SBAR tool, there was zero post-medication error. There was a significant decrease in the incidence of medication errors following the use of the SBAR tool. Thus, the use of the SBAR tool by nurses during the nurse handoff decreased the incidence of medication errors compared to not using the SBAR tool over a period of six weeks.

Table 9: Paired Samples Statistics

Figure 2 visually depict the pre- and post-SBAR results. “Setting” presented a mean increase of 2.34 points. “Organization/efficiency” presented a mean increase of 2.83 points. The “communication” score increased by 2.1 points. The “content” score increased by 2.9 points. The “clinical judgement” score increased by 3.1 points. “Humanistic qualities/professionalism” presented a mean increase of 1.93 points. “Overall sign-out competence” presented a mean increase of 2 points.

Interpretation

This project results revealed nurses’ use of the SBAR tool during nurse handoffs improved communication and decreased the incidence of medication errors. “Setting” presented a mean increase of 2.34 points. “Organization/efficiency” presented a mean increase of 2.83 points. The “communication” score increased by 2.1 points. The “content” score increased by 2.9 points. The “clinical judgement” score increased by 3.1 points. “Humanistic qualities/professionalism” presented a mean increase of 1.93 points. “Overall sign-out competence” presented a mean increase of 2 points.

There was a statistically significant improvement in setting CEX scores after the use of the SBAR tool. Thus, the use of the SBAR tool by nurses during the nurse handoff improved setting CEX tool scores. There was a statistically significant improvement in organization/efficiency following the use of the SBAR tool. Thus, the use of the SBAR tool by nurses during the nurse handoff improved organization/efficiency CEX scores. There was a statistically significant improvement in communication skills following the SBAR tool. Thus, the use of the SBAR tool by nurses during the nurse handoff improved communication skills CEX tool scores.

There was a statistically significant improvement in content CEX tool scores following the use of the SBAR tool. Thus, the use of the SBAR tool by nurses during the nurse handoff improved content CEX tool scores. There was a statistically significant improvement in clinical judgment scores following the use of the SBAR tool. Thus, the use of the SBAR tool by nurses during nurse handoff improved clinical judgment CEX tool scores.

There was a statistically significant improvement in humanistic qualities/professionalism following the use of the SBAR tool. Thus, the use of the SBAR tool by nurses during the nurse handoff improved humanistic qualities/professionalism CEX scores. There was a statistically significant improvement in overall sign-out competence following the use of the SBAR tool. Thus, the use of the SBAR tool by nurses during the nurse handoff improved overall sign-out competence CEX scores.

There were no medication errors reported during the time of SBAR implementation. Thus, the use of the SBAR tool by nurses during the nurse handoff decreased the incidence of medication errors. These findings supported the previous studies (Muller et al., 2018). Therefore, the results supported knowledge in the nursing discipline.

The project has had a significant social and practical impact on people and systems. The study’s findings can help people improve health care quality by decreasing errors and patient harm associated with handoff communication. The project’s findings can help systems strengthen the role of the DNP-prepared nurses by assisting them in conducting quality care and evidence-based research.

Limitations

In this study, there were a few limitations. The study included an auditor, and the providers were aware of it, affecting the authenticity of the handoff. It would have been advantageous to include two auditors. The Handoff CEX tool had a scoring system including nine points (e.g., 1, 2, 3=unsatisfactory, 4, 5, 6=satisfactory, 7, 8, 9=superior). It was hard to differentiate between the three selections. It would have been ideal to have revised the Handoff CEX tool, including three points (i.e., one=unsatisfactory, 2=satisfactory, 3=superior). Providers’ satisfaction was not measured even though they were satisfied with the improved process. It would have been advantageous to have measured providers’ satisfaction scores. Tell me more about the qualitative nature of your findings. What did the nurses have to say about the use of SBAR.

Implications for Advanced Nursing Practice

Numerous healthcare organizations have difficulty with realizing effective hand-off communication. The literature supports hand-off communication between nurses is necessary. However, nurses’ lack of attentiveness keeps them from adhering to this standard. Therefore, hospitals should implement a hand-off communication process using the SBAR tool to improve communication and patient outcomes and decrease medication errors. DNP prepared nurse leaders can improve hand-off communication processes by using the following TJC standards:

1. Showing leadership’s commitment to hand-offs.

-

- Enhance the health care organization’s approach to hand-offs.

- Provide resources to hand off quality improvement initiatives.

- Invest in training to maintain successful hand-off communication.

2. Standardizing vital content communicated by the sender during a hand-off

-

- Avoid using electronic or paper communications to create hand-offs.

- Use telephone or video conference to communicate.

- Communicate hand-off content in a timely way.

- Use disparate sources to synthesize information.

3. Conducting hand-off communication uninterruptedly and consisting of multidisciplinary team members.

-

- Use a compatible location and time for sign-outs.

- Share patient information by developing a workspace.

- Follow up by providing contact information.

- Share information with the patient and family simultaneously.

- Discuss, ask and answer questions using this time.

4. Standardizing training on how to conduct a successful hand-off.

-

- Enable staff to engage in training.

- Improve quality by placing coaches.

- Reward employees who successfully perform hand-offs.

5. Utilizing an electronic health record (EHR).

-

- Integrate an established standardized hand-off communication process into the EHR application.

- Provide vital information to enhance communications and feedback loops.

- Enable staff to access EHR.

6. Enhancing hand-off communication by monitoring the success of interventions.

-

- Ensure that team members’ use of hand-off methods is effective.

- Examine factors causing a poor hand-off and create solutions to them.

- Use data from adverse events with poor hand-offs as the basis for performance improvement.

7. Maintaining best practices in hand-offs and prioritizing high-quality hand-offs (TJC, 2017).

-

- Ensure reliable hand-offs.

- Use strong leadership and implement a program to enhance hand-off practices.

Tell me about how these concepts apply to your project.

Plan for Sustainability

One should use the SBAR tool to encourage communication and decrease the incidence of medication errors. An interdisciplinary team focusing on improved communication and the reduced incidence of medication errors will be organized to encourage the environment using the SBAR tool. Individuals interested in encouraging communication and decreasing the incidence of medication errors by using the SBAR tool will be gathered. Meetings and email correspondence attentive to communication and the incidence of medication errors will be required. Advantages, disadvantages, and any recommendations for enhancement will be discussed. Education will be continued, and all staff and their suggestions will be used to back up sustainability.

Organizational management approving the SBAR tool needs to be encouraged to support sustainability. Projects and the evidence supporting the SBAR tool should be disseminated to healthcare organization leaders. Clear communication with stakeholders should be done to support sustainability. In addition, stakeholder buy-in needs to be developed. Planning with clear objectives to improve communication and decrease the incidence of medication errors will be done to back up sustainability. A pilot initiative will be transferred into real practice. Communication will be extended to improve communication and decrease the incidence of medication errors.

Application of the AACN DNP Essential

Essential I: Scientific Underpinnings for Practice

The scientific underpinning concept for practice is the belief that the use of the SBAR tool by nurses during nurse handoffs improves communication and decreases the incidence of medication errors compared to not using the SBAR tool for six weeks. Using the SBAR tool should improve communication. Implementation of the SBAR tool was found to improve communication.

Essential II: Organizational and Systems Leadership for Quality Improvement and Systems Thinking

A new model of nurse handoff was developed to enhance productivity. Using the SBAR tool to improve communication and decrease the incidence of medication errors was a superior method supporting patient safety. A theory was successfully transitioned into practice by emphasizing the SBAR tool.

Essential III and IV: Clinical Scholarship and Analytical Methods for Evidence-Based Practice. Information Systems/Technology and Patient Care Technology for the Improvement and Transformation of Health Care

Analytical methods examining the impact of the SBAR tool were used to gather evidence for evidence-based practice. Comfort with the utilization of the CEX tool and SPSS was developed. The capability to collect and analyze data was developed.

Essential V: Health Care Policy for Advocacy in Health Care

This essential was applied to serve as a project expert to improve communication. The significant impact of the SBAR tool on communication was reviewed. In addition, the rationale for supporting the significant impact of the SBAR tool on communication was reviewed. Finally, questions and answers were available.

Essential VI: Interprofessional Collaboration for Improving Patient and Population Health Outcomes

Interprofessional collaboration with providers, DNP advisor, DNP mentor, and DNP chair was established. Efficient communication was used while developing interprofessional collaboration.

Essential VII: Clinical Prevention and Population Health for Improving the Nation’s Health

The project adheres to the seventh essential of the DNP Essential by benefits population’s health and improving clinical prevention through medical error reduction, which, in turn, increases the nation’s wellbeing and health. The project analyzes critical data from the target organization and synthesizes core concepts to develop and implement interventions through SBAR. The researcher examined the policies, analyzed data, presented the findings, and discussed the results.

Essential VIII: Advanced Nursing Practice

Participants were guided when they used the SBAR tool. A 30-minute in-service education session about the use of the SBAR tool was provided. Relationships were developed to support positive outcomes.

Conclusion

The Shock Trauma Unit helps patients cope with serious stress and provides psychological medical care. Unfortunately, medical errors caused by a disruption of communication between hospital staff are among the leading forms of errors in the healthcare sector. The use of the SBAR tool is designed to improve the effectiveness of communication between medical personnel to reduce the number of errors in taking medications.

Strengthening the regular use of the SBAR tool and standardized communication is a useful link in improving patient treatment outcomes. Thus, the possibility of submitting this evidence-based quality improvement initiative and findings to a group of colleagues becomes a useful ingredient in the evolution of a safety culture. Considering the clear risks to patient safety related to the transfer of medical services, particularly in the conditions of the shock trauma department, the outcomes were clinically relevant and encouraging. It is advisable to anticipate that continued enhancements will improve the transmission of patient information and restore patient safety. The results of this project have shown that the use of the SBAR tool in the conditions of the STU significantly reduces the likelihood of an error in the process of taking medications. The project can be spread to other contexts by examining the impact of the SBAR tool on patient safety in other departments. The project can continue to advance the practice change across other contexts by examining the effects of the use of the SBAR tool on other department patient safety metrics. How and when and why?

References

Abbasi, M. (2020). The impact of SBAR communication model on observance of patient safety culture by nurses of the Emergency Department of Shahid Beheshti Hospital in Qom in 1396. Iranian Journal of Nursing Research, 15(1), 49-58.

Achrekar, M. S., Murthy, V., Kanan, S., Shetty, R., Nair, M., & Khattry, N. (2016). Introduction of situation, background, assessment, recommendation into nursing practice: A prospective study. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing, 3(1), 45-50. doi:10.4103/2347-5625.178171

Allen, B. (2016). Effective design, implementation and management of change in healthcare. Nursing Standard, 31(3).

Birmingham, P., Buffum, M. D., Blegen, M. A., & Lyndon, A. (2015). Handoffs and patient safety: grasping the story and painting a full picture. Western journal of nursing research, 37(11), 1458-1478.

Belli, P., & Jeurissen, P. (2020). Hospital Payment Systems. In Understanding Hospitals in Changing Health Systems (pp. 121-138). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

Bereskie, T. A. (2017). Drinking water management and governance in small drinking water systems: integrating continuous performance improvement and risk-based benchmarking (Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia).

Bernard, H. R. (2013). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Sage Publications, Inc.

Bjarnadottir M., Anderson D., Zia L., Rhoads K. Predicting Colorectal Cancer Mortality: Models to Facilitate Patient‐Physician Conversations and Inform Operational Decision Making. Production and Operations Management. 2018; 27(12):2162-83.

Blake, Tim, and Tayler Blake. “Improving therapeutic communication in nursing through simulation exercise.” Teaching and Learning in Nursing 14.4 (2019): 260-264.

Britton, M. C., Hodshon, B., & Chaudhry, S. I. (2019). Implementing a warm handoff between hospital and skilled nursing facility clinicians. Journal of Patient Safety, 15(3), 198-204.

Bukoh, M. X., & Siah, C. J. R. (2020). A systematic review on the structured handover interventions between nurses in improving patient safety outcomes. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(3), 744-755.

Campbell, D., & Dontje, K. (2019). Implementing bedside handoff in the emergency department: A practice improvement project. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 45(2), 149-154.

Canale, M. (2018). Implementation of a standardized handoff of anesthetized patients. American Association of Nurse Anesthetists Journal, 86(2), 137-145. Web.

Carson-Newman University (2021). By the numbers: Nursing statistics 2021. Web.

Castelino, F., & Latha, T. (2015). Effectiveness of protocol on situation, background, assessment, recommendation technique of communication among nurses during patients’ handoff in a tertiary care hospital. International Journal of Nursing Education, 7(1), 123-127. Web.

Clanton, J., Clark, M., Loggins, W., & Herron, R. (2018). Effective handoff communication. Vignettes in patient safety. London: IntechOpen, 2, 25-44.

Clarke, S., Clark-Burg, K., & Pavlos, E. (2018). Clinical handover of immediate post-operative patients: A literature review. Journal of Perioperative Nursing, 31(2), 29-35.

Conover, K. M. V. B., Cummings, D., & Walsh, J. A. Simulation patient handoff and SBAR for second-year prelicensure nursing students.

Cousins, D. H. (2021). Medication errors. In Paediatric clinical pharmacology (pp. 245-264). CRC Press.

Cullen, L., Hanrahan, K., Farrington, M., DeBerg, J., Tucker, S., & Kleiber, C. (2017). Evidence-based practice in action: Comprehensive strategies, tools, and tips from the University of Iowa hospitals and clinics. Sigma Theta Tau.

Dalky, H. F., Al-Jaradeen, R. S., & AbuAlRrub, R. F. (2020). Evaluation of the situation, background, assessment, and recommendation handover tool in improving communication and satisfaction among Jordanian nurses working in intensive care units. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 39(6), 339-347.

Daniel, L., Hristov, S., Lyu, X., Stove, A. G., Cherenkov, M., & Gashinova, M. (2017). Design and validation of a passive radar concept for ship detection using communication satellite signals. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems, 53(6), 3115-3134.

Deal, J. (2020). Nurse-to-nurse handoff communication using the TeamSTEPPS approach.

DeNisco, S. M. (2021). Advanced practice nursing: Essential knowledge for the profession (4th ed). Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC.

Dingle, I. (2019). Development and Evaluation of a Women’s Health Nurse Practitioner Directed End of Shift Handoff Tool to Standardize Obstetrical Provider Communication in an Academic Medical Center. [Publication No. 22618078]. [Doctoral dissertation]. Wilmington University (Delaware). ProQuest Dissertations Publishing

Dontje, Campbell, Denise, and Katherine. “Implementing bedside handoff in the emergency department: A practice improvement project.” Journal of Emergency Nursing 45.2 (2019): 149-154.

Ellis, P., & Abbott, J. (2018). Applying Lewin’s change model in the kidney care unit: movement. Journal of Kidney Care, 3(5), 331-333.

Esaka, A. R. (2020). Development and Evaluation of a Nurse Practitioner-Directed Transfer Process for Patients Admitted to an Observation Unit in an Academic Medical Center {Publication No. 28030774}. [Doctoral dissertation]. Wilmington University (Delaware). ProQuest Dissertations Publishing

Etemadifar, S., Sedighi, Z., Masoudi, R., & Sedehi, M. (2020). t care intensive the in making-decision clinical’nurses on gram-pro training safety patient based-SBAR of effect the of Evaluation. Journal of Clinical Nursing and Midwifery, 9(2).

Fleiszer, A. R., Semenic, S. E., Ritchie, J. A., Richer, M., & Denis, J. (2015). The sustainability of healthcare innovations: a concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(7), 1484-1498. Web.

Francis, N. (2020). Development and Evaluation of Nurse Practitioner-Directed Rooming Handoff Protocol in a Primary Care Practice. Wilmington University (Delaware).

Fryman, Craig, Carine Hamo, Siddharth Raghavan, and Nirvani Goolsarran. A quality improvement approach to standardization and sustainability of the hand-off process. BMJ Open Quality 6, no. 1 (2017): u222156-w8291.

Funk, E., Taicher, B., Thompson, J., Iannello, K., Morgan, B., & Hawks, S. (2016). Structured handover in the pediatric postanesthesia care unit. Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing, 31(1), 63-72.

Halt, S. L. (2020). Mindful Meditation through the Use of Headspace to Reduce Medication Errors in the Obstetrical Inpatient (Doctoral dissertation, Grand Canyon University).

Harris-Hines, N. (2020). Development and Evaluation of a Nurse Leader-Directed Nurse-To-Nurse Handoff for Patients Transitioning from the Emergency Department to an Inpatient Unit Within a Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Wilmington University (Delaware).

Hasan, H., Ali, F., Barker, P., Treat, R., Peschman, J., Mohorek, M., Redlich, P., Webb, T. (2017). Evaluating handoffs in the context of a communication framework. Surgery, 161(3), 861-868. Web.

Hee, O. C., Cheng, T. Y., Ping, L. L., Kowang, T. O., & Fei, G. C. (2019). Embracing Change Management Strategies in Bedside Shift Report (BSR): A Review. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 9(1).

Hernandez, J. (2020). Trenton, NJ 08625. To the State Health Planning Board of New Jersey: We write regarding hospital chain Prospect Medical Holdings’ pending change in ownership. Safety net hospital chain Prospect Medical Holdings operates seventeen hospitals in five states, including East Orange General Hospital in New Jersey. i. Cell, 925, 324-4091.

Horwitz, L. I., Dombroski, J., Murphy, T. E., Farnan, J. M., Johnson, J. K., & Arora, V. M. (2013). Validation of a handoff assessment tool: The Handoff CEX. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(9-10), 1477-1486.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement (2019). Surveys: Nurse and physician attitudes about communication and collaboration. Web.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement (2020). Tools. Web.