Executive Summary

In Saudi Arabia, health outreach programs have emerged as the most effective ways for bridging some of the health gaps that exist in the prevention and management of non-communicable diseases. Particularly, their importance in the management of cancer has surpassed other groups of diseases because of the need for skilled professionals and advanced medical equipments to manage it. Many rural populations in the kingdom lack these resources. Therefore, referral hospitals in the kingdom have taken the initiative to address this challenge by introducing outreach programs to these communities. King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre (KFSHRC) is one such referral hospital. The aim of this paper is to find out the effectiveness of KFSHRC’s health outreach programs. Its objectives strive to understand the nature of these programs and estimate their benefits to Saudi Arabia.

Introduction

Limited access to health resources is a challenge that has not diminished in importance in the last decade (Hoffman 2012). Concisely, since the publication of the 2006 World Health Report, experts still report about the lack of skilled personnel, brain drain, unequal distribution of resources, shortage of health workers and such problems in most developed and developing societies (World Health Organization 2011). These problems have consistently affected the quality and access to health care services around the world (Hoffman 2012). Beyond the generalizations that often accompany debates to solve such problems, it is important to understand that different countries have their unique health challenges. Since there is a need for developing customized solutions to solve them, no proposal should be undermined. This fact stems from the need to explore a wide selection of alternatives for improving the access to health services and increase the quality of care given to patients. Particularly, this need is dire for populations that live in marginalized areas because they lack access to preventive, treatment and diagnostic services (World Health Organization 2011). Here, Meade and Menard (2007) emphasize the need for developing sustainable alternatives because they need to contribute to increased job satisfaction and retention of health workers.

Managing non-communicable diseases, such as cancer, has become difficult for underserved communities because of the above-mentioned problems. People who suffer from this condition also suffer from high mortality and morbidity rates because of the poor access to diagnostic services, early screening services, and palliative care (Hoffman 2012). Different health systems have unique solutions to address this problem. However, health outreach programs have stood out as effective tools for improving cancer education and expanding screening services for community members that lack direct access to these health services. This observation is true for most Middle East countries. To explain the purpose of health outreach programs, Meade and Menard (2007) say, “They assist communities, cancer centers, and hospitals reach mutually beneficial goals that would otherwise not be achievable for promoting accessible and equitable cancer care for at-risk and hard-to-reach groups” (p. 71).

In Saudi Arabia, health outreach programs have emerged as the most effective ways for bridging some of the health gaps that exist in the prevention and management of non-communicable diseases. Particularly, their importance in the management of cancer has surpassed other groups of diseases because of the need for skilled professionals and advanced medical equipments to manage it (Mohamud 2015). Many rural populations in the kingdom lack these resources. Therefore, referral hospitals in the kingdom have taken the initiative to address this challenge by introducing outreach programs to these communities (Mohamud 2015). King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre (2013) (KFSHRC) is one such referral hospital.

Established in 1975, KFSHRC is a leading referral hospital in Saudi Arabia with branches in Jeddah and offices in other parts of the kingdom. Its vision statement is to be “a world-leading institution of excellence and innovation in health care” (King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre 2013, p. 1). According to the institution’s website, its mission statement reads, “King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre provides the highest level of specialized healthcare in an integrated educational and research setting” (King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre 2013, p. 1). Some of the key values driving the institution include patient focus, integrity, quality, compassion, and teamwork. The institution has 18 departments that pledge to uphold these values (King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre 2013). Home to more than 11,000 employees who hail from more than 60 nationalities, KFSHRC sits on 920,000 square meters. Its bed capacity is more than 900 (King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre 2013).

The hospital is a leading oncology center in Saudi Arabia because up to 30% of cancer patients receive treatment at this facility (Helen Ziegler and Associates 2015). In fact, the facility treats up to 70% of patients who suffer from certain cancers in the kingdom (Helen Ziegler and Associates 2015). For example, it treats up to 70% of pediatric care patients (Saudi Health Council 2014). In 2013, the hospital’s records showed that its doctors had treated more than 70,000 cancer cases (King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre 2013). Considering it is a member of major international health care groups, the facility has carved a name for itself as a leading center for excellence in oncology, not only in the kingdom, but also in the wider Middle East region (Mohamud 2015). Besides being a leading oncology center, the health facility is also a known health facility, for sensitive surgeries, such as organ transplants and cardiac surgeries (Helen Ziegler and Associates 2015). Experts also say it is a leading center for treating genetic diseases (Helen Ziegler and Associates 2015). Most of the health services offered by the facility are concentrated in its Riyadh facility. This concentration leaves most of the people who cannot gain access to this location severely underserved.

Research Problem

Decades of research have seen the translation of academic knowledge in public health practice to reduce the frequency and incidence of cancer (World Health Organization 2011). However, the benefits of such progress have not permeated through all cadres of society. Ethnic, racial, regional, and socioeconomic differences have mainly defined how human populations benefit from such developments (Baird & Wright 2006). Although medical research has increased cancer survival rates, it is difficult to ignore the health gaps that have consistently defined cancer outcomes in different societies. For example, people who live in rural areas, or remote parts of a country, tend to suffer from inadequate access to health care facilities. Therefore, they have higher health care needs than those who live in urban areas. While some of them may have access to primary care facilities, most of them do not have access to secondary, or tertiary, health care services because of the possible lack of skilled professionals and the lack of specialized health equipments (among other factors) (Baird & Wright 2006). To bridge such health delivery gaps, it is important to use acceptable and beneficial cancer interventions and health communication channels to improve the health infrastructure in rural communities. America, for example, uses the Healthy People 2020 objectives to guide its cancer management efforts (World Health Organization 2011). Most of such interventions strive to address the unequal burden of cancer across different communities. In Saudi Arabia, KFSHRC has taken a leadership role in bridging this health gap through its outreach programs, which strive to increase access to specialist services for communities that cannot access them. However, the efficacy and impact of these programs are unknown. This paper seeks to fill this research gap.

Purpose Statement

The purpose of this paper is to assess the impact of outreach programs in the health care delivery of King Faisal Specialist Hospital. Although these outreach programs should address several health issues, this paper mainly focuses on their impact in addressing cancer as a significant health issue in the kingdom.

Research Aim

- To find out the impact of outreach programs on the health care delivery of KFSHRC

Research Objectives

- To find out the types of Health Outreach Programs undertaken by KFSHRC

- To estimate the benefit of KFSHRC’s health outreach programs

Literature Review

In this literature review, we analyze what other researchers have written about the research issue. This chapter contains information surrounding the demand for oncology and tertiary health services in Saudi Arabia, the economic burden of cancer in Saudi Arabia, and the role of primary care in cancer prevention and control. Although the literature discusses these issues in different contexts, this chapter primarily focuses on their application and relation to KFSHRC’s health outreach programs.

Growing Demand for Oncology and Tertiary Health Services

Since the discovery of oil, Saudi Arabia has made tremendous progress in different aspects of its social and economic development. It has made such progress in the health care sector because the World Health Organization (2011) has ranked it at number 26 in W.H.O’s global rankings of countries with the best health care services (Mohamud 2015). However, the disease burden created by an increase in non-communicable diseases has put a tremendous pressure on the country’s health care system (Saudi Health Council 2014). Cancer is one of these diseases and is a serious health problem in Saudi Arabia. Globally, there are 11 million new cancer cases diagnosed annually (Mohamud 2015). Experts estimate that this number could increase to 15 million in 2020 (Mohamud 2015). This increase is sustainable on the back of a rapidly ageing population in both developing and developed countries (Baird & Wright, 2006). Similarly, the increased prevalence of unhealthy lifestyle habits, such as drinking and smoking, will worsen this trend (Baird & Wright 2006).

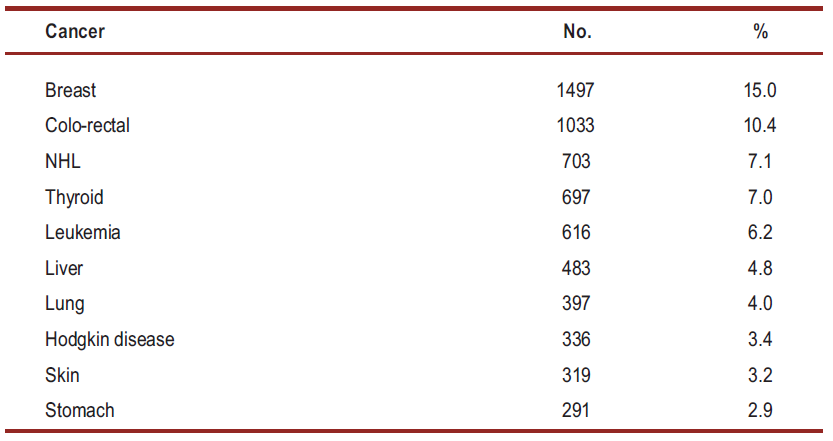

Saudi Arabia is not immune to this trend because the Saudi Cancer Registry says there are more than 13,706 new cases of cancer annually (Sebai 2014). KFSHRC diagnoses most of these cases. In 2011, it diagnosed 2,527 cases of cancer (King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre 2013). This figure represents 23% of all cancer cases reported by the Saudi Cancer registry (this registry contains reports of all cancer cases in the kingdom) (Saudi Health Council 2014). Health experts estimate that new cancer diagnoses should rise to 30,000 cases in the next 15 years (Mohamud 2015). The number of cancer cases among women is more than the number of cases that involve men because health reports show that the incidence of cancer among women is 4% higher than in men (Sebai 2014). The ratio is 92:100 (Saudi Health Council 2014). Recent estimates show that there were 10,320 cases of cancer among Saudi citizens, while the cases among non-citizens are 3,265 (Saudi Health Council 2014). There are even fewer cases among people of unknown nationalities. The age-specific incidence rate of the disease increases as people age. This is true for both men and women (Saudi Health Council 2014). After 64 years, men suffer the highest risk of developing cancer. In Saudi Arabia, men have a median age of diagnosis of 58 years, while women have a median age of diagnosis of 51 years (Mohamud 2015). The Eastern Region of Saudi Arabia has the highest number of cancer cases, followed by Riyadh, Tabuk, Qassim, and Makkah regions (Saudi Health Council 2014). The ten most common types of cancer in Saudi Arabia are breast, colorectal, NHL, thyroid, leukemia, liver, lung, Hodgkin disease, skin cancer and stomach cancers (Saudi Health Council 2014). The table below shows the incidence of these cancers in the Saudi population

Breast cancer is the most common type of cancer among women. Comparatively, colorectal cancer is the most common types of cancer in men (Sebai 2014). Compared to other parts of the world, colorectal cancer is common among young (Sebai 2014). The same is true for Saudi Arabia because health researchers say doctors commonly diagnose this disease among Saudis who are aged 30 years and above (Saudi Health Council 2014). Therefore, people who are within the age bracket of 30-74 suffer the highest risk of developing this type of cancer. In women, breast cancer is the most common type of cancer for all age groups. The most common endocrine malignancy for this gender is thyroid cancer (Mohamud 2015). However, its occurrence varies across ethnic and geographic divisions. Thyroid cancer is the second common type of cancer among Saudi females and the third leading type of cancer among men (Mohamud 2015). Comparatively, children often suffer from leukemia and Hodgkin’s disease. Lung cancer is the most common type of cancer for the elderly (especially among men who are aged 45 years and beyond) (Saudi Health Council 2014). Liver cancer is more common among Saudi men who are older than 75 years (Mohamud 2015). It is the leading type of cancer in this age group. However, as the age decreases, it decreases in frequency. The incidence of genitor-urinary cancer in Saudi Arabia is 9.2% (Saudi Health Council 2014). Although its incidence increases in age, Saudi men are five times more likely to develop it, compared to their female counterparts (Saudi Health Council 2014). Bladder, prostate, kidney, and testicular cancers are mostly common among this gender (Saudi Health Council 2014).

The rate of cervical cancer is lower in Saudi Arabia than other Middle Eastern states and the world. While some observers attribute this phenomenon to cultural influences (low risk of transmission through multiple sexual partners), others attribute it to underreporting (Mohamud 2015). Nonetheless, there are 152 cases of cervical cancer reported annually (Mohamud 2015). About one-third of this population dies from the disease. However, as the population ages, experts predict a dramatic surge in cervical cancer cases (Sebai 2014). Indeed, by 2025, they estimate that the number of new cases would probably double, while the number of deaths would increase to 117 people (Sebai 2014). Although cervical cancer is preventable, doctors diagnose most of the cases in Saudi Arabia when they are in advanced stages. This is largely due to the lack of screening services. Skin cancer is also a common type of cancer in the kingdom. However, its incidence is higher among people who are aged over 60 years (Mohamud 2015). Most of the people who suffer from this condition had a barcal cell carcinoma and aquamous cell carcinoma diagnosis (Mohamud 2015). Some of them also had a Kaposi Carcinoma diagnosis (Mohamud 2015). Melanoma is a rare neoplasm associated with skin cancer, but its incidence in Saudi Arabia is lower than other parts of the world (Sebai 2014). Oral cancer is also another rare type of cancer in Saudi Arabia. However, regional boundaries define its frequency. For example, it is common in Jizan and Najran (women are mostly affected) (Saudi Health Council 2014).

The increased disease burden caused by a surge in the number of the above-mentioned cancers has had a toll on Saudi Arabia’s health infrastructure. The country’s inadequate health infrastructure is partly responsible for this problem. For example, the lack of adequate cancer screening facilities has contributed to the number of advanced stage diagnoses (Younge et al. 1997). Furthermore, some places that have screening services suffer from the ineffectiveness of the same services (Knaul 2012). A related problem is the kingdom’s poor record of cancer prevention. For example, health experts say it has a poor record of preventing breast cancer (Helen Ziegler and Associates 2015). Furthermore, at different levels of care, there are significant gaps between knowledge and practice.

Economic Burden of Cancer

Global cancer statistics reveal that European men and sub-Saharan women bear the greatest economic burden of cancer (Mohamud 2015). Breast, Colorectal, lung and prostate cancers have the greatest economic effects on families by virtue of being the most common types of cancers in the world (Knaul 2012). In fact, different estimates project their economic burden to be between 18% and 50% of all cancer costs (Mohamud 2015). Saudi Arabia is the largest economy in the Middle East and the 24th biggest economy in the world (Helen Ziegler and Associates 2015). As shown in the first chapter of this paper, the Saudi Arabian government has invested many resources in the country’s health system. From this commitment, the number of resources allocated to this sector has improved consistently over the years. The World Bank says Saudi Arabia’s spending in this sector represents 4.3% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Helen Ziegler and Associates 2015). The share of GDP contributions from the public health sector is 2.7%, while that of the private sector is 1.6% (Mohamud 2015). The health expenditure of the Saudi government to the country’s health industry is SR 91.2 billion (Mohamud 2015). This amount is equivalent to $24.35 billion. In 2011, this amount represented a 16% increase in state expenditure in the health sector, compared to 2010 (Mohamud 2015). Health experts project that the state’s expenditure in this sector will steadily increase to SR117 billion in 2017 (Helen Ziegler and Associates 2015). They say so because they believe many Middle East countries will experience a significant rise in the demand for health care services in the next few years (Helen Ziegler and Associates 2015). This trend could see the total health care spending by these governments reach $60 billion (Mohamud 2015).

Although the rate of cancer in Saudi Arabia is lower than its Middle East neighbors and other western nations, Baird and Wright (2006) say the country needs to prepare itself to address the health needs that are emerging from increased cancer cases stemming from the country’s growth and its increasingly ageing population. There is little doubt that this trend would lead to a strain on the country’s health infrastructure (World Health Organization 2011). KFSHRC has taken up this challenge through its health outreach programs, which strive to provide such services to patients who live in remote parts of the country. They have also strived to maintain a high quality of health care service as they do so (King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre 2013). This strategy has seen the hospital set up many small and large cancer centers in different parts of the country. The government has also invested many resources in training physicians to work in the oncology department (Saudi Health Council 2014). It has also licensed several governmental and non-governmental agencies to undertake responsibilities bordering on cancer control (Saudi Health Council 2014). Their responsibilities have mostly centered on screening and early detection programs. Nonetheless, as this paper has shown, most of the cancer diagnosis cases in the kingdom have happened when the disease has progressed to advanced stages (Mohamud 2015). This situation adds to the country’s strain and economic burden of cancer. The fact is that limited resources to mange cancer and the presence of economic, social and political constraints in Saudi Arabia make it difficult for the country to fight the disease (Mohamud 2015). This problem is bigger in the public sector, as opposed to the private sector. In the kingdom, most of the resources allocated for managing cancer go to the provision of tertiary health care services without a clear balance of its distribution in different aspects of cancer management, such as prevention, early detection and palliative care (Saudi Health Council 2014). Nonetheless, there is a continuing increase in health expenditures allocated to pharmaceutical spending and the purchase of medical equipment (Saudi Health Council 2014). For example, there has been a 13% increase in pharmaceutical spending from 2011 to 2012 and an increase of expenditure to purchase equipment from SR 5.54 billion to SR 6.53 billion within the same period (Mohamud 2015). These figures show that Saudi Arabia spends a lot of money in managing non-communicable diseases. Therefore, the economic burden of the disease continues to weigh on the government and its citizens.

Role of Primary Care in Cancer Prevention and Control

The 1978 Alma-Ata declaration considered primary health care a significant milestone in the achievement of health outcomes (Mohamud 2015). Primary care plays a critical role in health promotion and in the promotion of health education. Its importance in these functions comes from the fact that primary care is the first point of contact between patients and health care service providers (Baird & Wright 2006). Most health practitioners believe that most people hold the most power in realizing the success of this relationship because they are the protectors of their health and at the same time, the source of resources to make the health system work (Rose 2013). After the adoption of the Alma-Ata declaration, the Saudi government decided to use primary care as a key health strategy. This is why in the 80s, the government decided to include primary care health facilities as part of the national health care network (Mohamud 2015). The purpose of doing so was to allow people to live healthy, safe, and independent lives. Nonetheless, the success of primary care services has always depended on the monitoring and improvement efforts of the government. Its success has also depended on the successful allocation of adequate resources, the acceptance of primary care by the Saudi community and the extensive use of health education approaches (Rose 2013). The implementation of health insurance policies and the training of primary health care givers could also improve the success of primary health care services (Rose 2013). These efforts could help all stakeholders cope with current methods of health care service provision.

Gorin (2013) says, among the most successful ways of managing cancer cases is to shift its management paradigm to be more focused on primary care, as opposed to tertiary care. He believes this approach would increase the efficacy of screening efforts and increase cases early detection (Gorin 2013). He also believes this approach would improve survival rates and improve responses to the needs of patients who receive palliative care (Gorin 2013). Family physicians could play an important role in making these suggestions work because their effectiveness in health promotion and their success in encouraging their patients to go for cancer screening programs is uncontested (Rose 2013). They also have a good record of making follow-ups after their patients receive cancer management services (Rose 2013). Avoiding unhealthy lifestyle habits and managing obesity are some of the current proposals made by health practitioners to reduce the risk factors of the diseases in the primary care setting. The improvement action on primary care services have mostly focused on eliminating barriers to health care service delivery and the promotion of universal health care coverage (Helen Ziegler and Associates 2015). Quality health care services often align with the core values and principles surrounding primary care (Mohamud 2015). Health care disparities are bound to undermine efforts to use primary care as an effective tool for managing cancer. Similarly, they are likely to undermine the need for an integrated management of primary care in the cancer management strategy of Saudi Arabia. Such disparities are bound to negatively affect the health of populations and create unnecessary costs in the provision of health care services (Mohamud 2015).

Rose (2013) says primary health care has shown tremendous success in controlling communicable diseases through vaccinations and immunizations. She argues that the same record does not exist in the prevention of non-communicable diseases, such as cancer (Rose 2013). However, other researchers believe there is a lack of empirical evidence to support this fact (Meade & Menard 2007). Owing to this discrepancy, Mohamud (2015) reviewed more than 30 articles published in 2006 to evaluate the quality of primary health care services in Saudi Arabia and found out that they had a poor performance in chronic disease management. Similarly, he established that they had poor scores in health education and referral systems (Mohamud 2015). Several factors emerged as the main reasons for these poor scores. They include “management and organizational factors, poor implementation of evidence-based practice, inadequate professional development, misuse of referrals to secondary care, and different organizational cultures” (Mohamud 2015, p. 58). Gorin (2013) says since health care service providers are the main sources of human capital in primary care settings, any shortage would reflect in poor quality health care services. This outcome would also manifest in the poor implementation of early detection efforts and the poor control of the risk factors that cause cancer (Gorin 2013). Employee satisfaction is a critical part of this equation because Mohamud (2015) says it plays a critical part in the preservation of skilled health care personnel that would make health care services work.

Multiple studies to evaluate the level of job satisfaction in Saudi Arabia showed that most skilled staff was dissatisfied with their jobs (World Health Organization 2011). The level of dissatisfaction was higher for practitioners working in rural areas. This dissatisfaction level had a direct and indirect effect on their motivation to provide quality health care services. Some of the key factors causing dissatisfaction levels included

“Unsuitable working hours/shifts, lack of facilities, inability to match work with family needs, inadequacy of family leave time, poor staffing, management and supervisory practices, lack of professional development opportunities, and inappropriate working environment in terms of the level of security, poor patient care supplies and equipment” (Mohamud 2015, p. 58).

A study conducted in one rural part of Saudi Arabia (Asir region) showed that this place lacked essential resources for managing non-communicable diseases (Mohamud 2015). Few health care professionals understood how to manage primary health care services using evidence-based practice. Al-Aimaie (a health researcher) conducted further studies in the Eastern Area of Saudi Arabia by assessing the attitudes of 409 physicians regarding evidence-based practice and found out that only 108 (39% of them) understood what “evidence-based practice” meant (Mohamud 2015). However, his overall findings revealed that the majority of them had positive attitudes towards it (Mohamud 2015). Baird and Wright (2006) say, having an effective referral strategy is an important requirement for the delivery of quality care in some of these rural areas. They also say it is an important requirement for the delivery of high quality, comprehensive and integrated health care services (Baird & Wright 2006). Different researchers have conducted several studies to evaluate the quality of these referral services in Saudi Arabia and found out that most of them were of poor quality (Mohamud 2015). Some of the factors that have caused this problem include “incomplete forms, unclear handwriting, poor medical skills, carelessness, insufficient space for history, lack of communication, and lack of feedback notes to the primary care centers” (Mohamud 2015, p. 58).

Summary

This literature review has shown that many rural populations suffer from inadequate access to early detection health services and cancer screening services. The lack of specialized equipment to provide specialized care also contributes to the high number of cancer deaths and late diagnosis cases in this demographic. KFSHRC has introduced several health outreach programs to address some of these problems, but few literatures have explained their impact on the community. Subsequent chapters of this paper strive to address this issue. The methodology chosen to undertake the study appears below.

Methodology

The aim of this paper is to explore the effectiveness and efficiency of the health outreach programs outlined by KFSHRC. It also strives to understand the nature of existing outreach programs and identify opportunities for improving their effectiveness. This chapter of the paper explains the methods used to conduct this study. It contains information about the research approach, research design, data collection methods, data analysis methods, and limitations of the study.

Research Approach

This paper has a mixed research design, which contains both qualitative and quantitative aspects of research (Creswell & Clark 2011). The interchange of these methods stem from the nature of the research question, which strives to investigate the cost-benefit analysis of KFSHRC’s health outreach programs. The qualitative element of the research question strives to explain the subjective factors of the outreach programs, while the quantitative element strives to highlight the figures and statistics surrounding the implementation of the outreach programs. For example, the cost savings accrued from implementing these programs emerge from this research design. However, the factors surrounding the efficacy of the programs appear in the quantitative section. Onwuegbuzie and Combs (2011) say there are five justifications for using the mixed methods research design. The first three justifications include triangulation (comparing qualitative with quantitative findings), complementation (using one analysis to expand or enhance the findings of another) and development (the findings of one analysis are used to inform data collected in another analysis) (Onwuegbuzie & Combs 2011; Hesse-Biber 2010). The last two methods include initiation (to highlight contradictions and paradoxes when formulating the research question) and expansion (the use of both qualitative and quantitative analyses to expand the research focus) (Onwuegbuzie & Combs 2011; Hesse-Biber 2010). The purpose of choosing the mixed method design was “development” because the quantitative data obtained informed the data collected in the qualitative assessment (Creswell & Clark 2011). The analysis is a qualitative dominant-mixed analysis because it emphasizes more on the qualitative aspect of the analysis as opposed to the quantitative aspect of it. Through a constructivist-poststructuralist-critical stance, the addition of the quantitative data helped to provide rich data. These factors outline the justification for using the mixed methods research approach.

Research Design

In this paper, we used the exploratory research design because few studies have investigated the impact of outreach programs on the health care delivery of KFSHRC. This research design helped us to gain insight and familiarity with the research topic and have a grounded picture of the research issue. Through the findings obtained from the design, it would be possible to investigate the reasons for the findings highlighted in this paper, in the future (Hair 2015). For example, this research design would allow future researchers to investigate why the outreach programs have the impacts outlined in this paper. The exploratory nature of the study also gave room to ask different types of questions, during the process of formulating the research questions, including questions that investigated the “what, why and how” of KFSHRC’s outreach programs.

Data Collection

We collected the evidence gathered in this paper from different sources of data, including a review of the program documentation and analysis of its related data.

Therefore, the findings of this paper stem from a secondary review of publications about KFSHRC’s outreach programs. These sources of information helped to estimate particular parameters of analysis. For example, the supplementary sources of information obtained from health reports provided a critical understanding of health outreach programs, but did not outline the explicit focus of the paper. We obtained program data from the health outreach programs undertaken since 2000. To understand the nature of these outreach programs, we also evaluated data from prior years. The data obtained through such sources of information reflected aggregate findings about hospital visits, planned outreach visits and the accurate figures and costs associated with the outreach programs. This program data included important details surrounding the following factors

- A schedule of agreed outreach activities including the budget and the actual level of funds

- A review of the actual number of consultations totaling the approved services offered in the health outreach programs. We collected the data from completed and successful outreach programs.

Data Analysis Methods

There are many types of data analysis methods in mixed methods research. They include “data transformation, typology development, extreme case analysis, and data consolidation” (Greene 2007, p. 146). In this paper, we used the data consolidation technique as the main type of data analysis method. It involves a joint review of both qualitative and quantitative data types to create a new typology for analysis in further studies, which does not lean on either side (Greene 2007). For purposes of this review, we analyzed both qualitative and quantitative data indiscriminately to come up with a holistic understanding of the impact of KFSHRC’s health outreach programs. The quantitative data helped to create a pattern of analysis, which was subject to further analysis through qualitative data assessments. In some instances, we had to transform the quantitative data into a narrative (qualitative) to have a broader understanding of emerging themes and patterns in the analysis.

Limitations of Study

The limitations of a study refer to factors that are beyond the control of the researcher. These factors place restrictions on the methodology chosen and the conclusions developed in the study. The main limitations of this study appear below

Lack of Available Data

Saudi Arabia is a relatively “closed” society. Although the sources of information used in this paper were useful in understanding the efficacy of existing outreach programs, their limited availability undermined the research. Conversely, it was difficult to affirm the credibility of the research information available. It was also difficult to find sufficient data regarding the health outreach programs undertaken by KFSHRC because of the lack of transparency in the Saudi Arabian health care system. This limitation made it difficult to establish trends and patterns when investigating the impact of these outreach programs.

Limited Prior Studies on the Topic

The availability of prior research studies on a topic makes it easy to write a literature review. Similarly, it helps researchers to understand the research topic under investigation. However, there were few research topics to use as background information in this study. Therefore, the limited number of prior studies limited the scope of information available to the researcher.

Findings

The aim of this paper is to find out the effectiveness of KFSHRC’s health outreach programs. Its objectives strive to understand the nature of these programs and estimate their benefits to the community. This chapter highlights the findings of this assessment by explaining the different types of health outreach programs in KFSHRC and estimating their financial benefits to the population. These insights help to understand their effectiveness. However, before delving into the details of this analysis, it is important to comprehend the importance of these programs.

Importance of Outreach Programs

The purpose of a health outreach program is to provide health services to communities, or people who would otherwise have not received the service by virtue of being unable to visit a health facility (Mufti 2007). Health outreach programs are important to Saudi Arabia because the kingdom has geographic and demographic challenges that predispose some of its population to health challenges that health care service providers cannot tackle through the conventional health care system. For example, there are only three developed cosmopolitan areas in Saudi Arabia (Riyadh, Jeddah, and Dammam-Al Khobar-Dhahran), which serve people living within a 2.2 million square kilometer radius (Mufti 2007). The sheer size of the country poses an infrastructure challenge to patients who may want to access quality health care services because Saudi Arabia’s size is almost similar to the geographic size of Italy, France and the United Kingdom (U.K) combined (Mufti 2007). The lack of specialized hospitals in remote parts of Saudi Arabia highlights the importance of having outreach programs in the kingdom. People who are unable to access health services through such programs receive treatments through referrals to some of the specialized hospitals in the kingdom, such as KFSHRC. The following table shows the demographic profile of residents of Saudi Arabia

Table 1: Demographic profile of Saudi Arabia

(Adapted from Ali-Rayes 2014)

Compounding some of the health infrastructural problems of Saudi Arabia is the heavy disease burden of con-communicable diseases. For example, Saudi Arabia has among the highest incidences of diabetes in the Middle East and in the world. Health estimates show that 27% of the population is diabetic and 25% of this demographic has a high probability of developing the disease (Ali-Rayes 2014). Relative to this problem, “Compounding the situation are the lifestyle diseases, changing disease pattern, ageing populations, rising health care costs, inequitable distribution of health care resources, medical skills, and access difficulties” (Ali-Rayes 2014: 1). KFSHRC tries to address some of these problems through its outreach programs. It has ten regional polyclinics, eight tele-ICU facilities, and five surgical locations (King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre 2013. A detailed understanding of the outreach programs in these facilities will appear in later sections of this paper.

Nature of KFSHRC’s Outreach Programs

A common characteristic of these outreach programs is the mobility of health personnel to reach vulnerable populations. The Health Outreach Services Department manages these programs. The role of this department is to provide mechanisms to improve care delivery through the information flow from KFSHRC to affiliate hospitals in the kingdom (King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre 2013). The goal of doing so is to avoid the physical and financial trouble associated with a visit to the hospital. The Health Outreach Services department has two main branches – Health Outreach Support and e-Health Services.

Health Outreach Support

The health outreach support branch plays different roles within the department that include training and education, implementation of national programs, facilitation of clinical visits, and facilitation of diagnostic visits (Ali-Rayes 2013). The facilitation of medical visits is a core function of the health outreach program (King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre 2013). It is the link between KFSHRC and other participating health institutions. Depending on the medical issue in question, these visits outline the medical, consultation, and technical solutions needed to manage a disease. These visits may manifest as consultation or diagnostic visits (Ali-Rayes 2013). Consultation visits often involve following up on previous visitations and arranging for patients to receive care in their localities. The patients may receive such care in specialized clinics operated by affiliated hospitals or partners (King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre 2013). Diagnostic visits should provide medical assessments for affiliated parties who may want to use some of the research facilities available at KFSHRC. In this way, they do not only have access to the hospital’s facilities, but also the hospital’s consultants and technicians.

Polyclinics are auxiliary centers established by KFSHRC to enhance patients’ referral systems. They also help to maintain high standards of quality care for patients, even if they do not go to the facilities (Ali-Rayes 2013). The hospital also established these facilities to minimize the traffic of patients in the outpatient service area, especially if the service they come to receive in the hospital is available in the health outreach regional polyclinics. Today, the hospital has 10 polyclinics around the kingdom that serve this purpose (King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre 2013). The scheduling process optimizes patient care, but efforts to promote these services are ongoing (King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre 2013). Still part of the hospital’s outreach program is the surgery program, which focuses on unifying and developing medical treatment and diagnostic facilities (Ali-Rayes 2013). These programs also promote service standardization for purposes of finding strategic solutions to the problems facing disease management. Several medical, health and training programs are products of this program. However, the training and education division is mostly concerned with encouraging medical staff to pursue technical extensive training in different departments of KFSHRC (Ali-Rayes 2013). Part of its role is coordinating and conducting symposia and workshops that act as educational zones.

Collectively, some of the services offered at these health outreach regional centers include patients’ referral services, national medical second opinion services, medication refills, blood transfer programs, appointments, patient discharge, and remedies for sudden medication run-outs (Ali-Rayes 2013). The success of the patient referral program depends on the application of information technology tools for its implementation. The Patients Acceptance Department manages all activities (administrative and medical) associated with this program. The department may accept or reject a patient with recommendations on available places for treatment. The national Medical Second opinion program involves the exchange of information and technical expertise concerning developed and modern ways of treatment (King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre 2013). This program acts as a foundation for the development of patient treatment programs in Saudi Arabia. Nonetheless, the medical refill program is among the most important programs of KFSHRC because it is crucial in safeguarding the efficacy of a patient’s treatment program (King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre 2013). Most patients who visit the facility receive medications that they are supposed to take at home because if they encounter medication run-outs or experience delays in taking these medications, they may suffer unnecessary physiological defects (Baird & Wright 2006). Therefore, the medication refill program strives to avoid such situations by sending medications to patients in a timely manner, with the patient’s name and information placed on the labeling (King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre 2013). The blood transfer program is also another service offered by KFSHRC at the request of its physicians. However, the patients who benefit from such services should have a medical number from the hospital (Ali-Rayes 2013). The sudden run-out of medication program is for patients who have lost or damaged their medication. Similarly, patients who have their medications changed may also benefit from this program. An ongoing appointment program is also essential to the functioning of the facility because it offers specialized services that are essential in planning for technical, administrative and medical functions of the institution. The hospital’s Case Management Department is responsible for the patient discharge program, which strives to improve the management of medical treatments in the facility (Ali-Rayes 2013). Patients benefit from this program by not experiencing delays in medical treatments or surgeries.

E-Health Services

In 1993, His Majesty King Fahad Bin Abdulaziz established the e-health services to increase collaboration between KFSHRC and American health and educational institutions (Rocha et al. 2015). Through the program, he also expected the hospital to collaborate with global health agencies, such as the World Health Organization (2011). KFSHRC has managed to expand this link by collaborating with global health agencies and other health facilities in the Middle East to provide quality health care services (Rocha et al. 2015). For example, through e-health platforms, KFSHRC has expanded its outreach program to Yemen and Bahrain. The same platform has also allowed KFSHRC to collaborate with 27 other hospitals in Saudi Arabia (King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre 2013). The e-health service operates via telemedicine and videoconferencing facilities. Management and coordination activities are important elements of the platform because they help in the dispensation of health care services. One key contribution of this program is the safeguard of high quality health standards for patients of KFSHRC.

The adoption of e-health has elevated Saudi Arabia to be among the leading countries in the adoption of the latest technological and communication services in the health sector (Rocha et al. 2015). Some of the services and achievements of this program include the establishment of a collaborative center with the W.H.O, the establishment of the hospital’s national e-health network, which links more than 20 regional hospitals, establishment of tele-education and telemedicine facilities, establishment of 27 remote regional clinics, establishment of e-services – Web, and the introduction of telemedicine services (Ali-Rayes 2013). The telemedicine services include patient consultations, tele-echo services (used to relay cardiology echo findings from affiliated hospitals to KFSHRC), tele-radiology services (this service is currently available at King Khalid Hospital, Tabuk, only), and tele-ICU services (Ali-Rayes 2013). The tele-ICU facilities use video-audio tools to link critical care doctors and their assistants to ICU facilities (Rocha et al. 2015). They mostly benefit doctors who are in rural areas. Some of the greatest successes associated with this technological platform are the reduction of waiting times and the increase of bed use in hospital facilities (Rocha et al. 2015). Similarly, it has helped to improve the quality of services offered in rural hospitals by providing elevated training facilities. Reports of improved patient outcomes are also true because this facility allows nurses and doctors to monitor their patients 24/7. The table below shows the current structure of KFSHRC’s e-health network.

Table 2: KFSHRC’s e-health network

Key

- Operational

f – Future plan

(Adapted from Ali-Rayes 2014)

Collectively, the outreach programs of KFSHRC have helped to improve the health outcomes of rural populations. Findings that estimate their financial savings appear below

Financial Savings of the Outreach Programs

Health experts in the Saudi Arabian health sector say medical outreach programs minimize the financial burden of health care by allowing patients to access quality health care in their localities (Mohamud 2015; Gorin 2013). These financial savings do not only accrue to the families involved, but also for the Saudi ministry of health through a decline in the use of health resources. Already, this paper has shown that KFSHRC’s outreach programs are in different parts of the country. King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre (2013) classifies these programs in three groups – polyclinics, tele-ICUs and national surgical programs. The map below shows their different locations in Saudi Arabia

This section of the paper demonstrates the cost savings generated by these programs.

Regional Polyclinics

Regional polyclinics are instrumental in reducing the financial burden of patients who may be required to visit referral hospitals for routine checkups (King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre 2013). Reducing the pressure on ambulatory care clinics is part of the goal of establishing these remote health centers (Ali-Rayes 2014). KFSHRC does so by assigning family medicine consultants and staff nurses to these facilities (King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre 2013). Part of the responsibility of these practitioners is to assess a patient and refer them to the regional polyclinics (Bergeron 2013). Once assigned to these clinics, a patient is supposed to follow the plan outlined in the referral note by attending these regional polyclinics. They offer different services to patients, including blood transfers, medication refills, and second opinion advices (King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre 2013). The existing technical infrastructure of these facilities taps into the health database of KFSHRC to provide such services. According to Ali-Rayes (2014), regional polyclinics have helped save SR 4,671,936 in transport and service delay costs. The cost breakdown of regional polyclinics appears in the table below

Table 3: Cost breakdown of regional polyclinics

(Adapted from Ali-Rayes 2014)

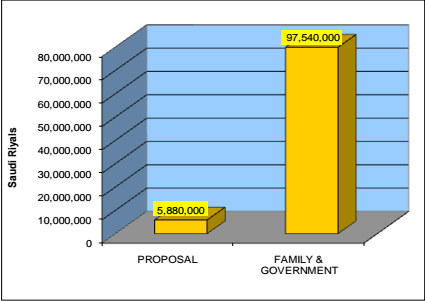

Current calculations that have evaluated the current cost savings associated with KFSHRC’s polyclinics estimate significant future savings for both patients and the government. To illustrate these cost savings, Ali-Rayes (2014) deduced that if 29,400 patients visit KFSHRC annually, they would most likely need more than 50,000 tickets (if a family member accompanies a patient). Since a ticket price to KFSHRC would cost SR 600, the total transport cost for the patient would be more than SR 35,000,000 (for patients and their family members). Based on the complexity of hospital services, such patients would spend a lot of time in the hospital because of the complex patient scheduling processes. Ordinarily, a patient could spend up to three nights in the city before a doctor attends to them (Ali-Rayes 2014). The total accommodation cost would be SR 24,660,000. The total cost for food and companionship could cost an extra SR 17,000,000. Consequently, the total cost of visiting KFSHRC in Riyadh could be in excess of SR 97 million (based on the assumption that 29,400 patients would visit the facility).

Polyclinics could significantly reduce this cost by reducing waiting times. This way, patients would spend less time in service delays. Their expenses would similarly decline (Bergeron 2013). As many people seek medical services at these polyclinics, the patients who seek ambulatory services would similarly decline (Bergeron 2013). The overall long-term effect would be an increase in appointment slots for new patients at KFSHRC and the indirect reduction of health care costs for the government (including the families of the patients). Pundits have also demonstrated that such health outreach programs could also improve health care access without compromising the quality of services offered (Ali-Rayes 2014). The cost comparison of this proposal appears below

Tele-ICU

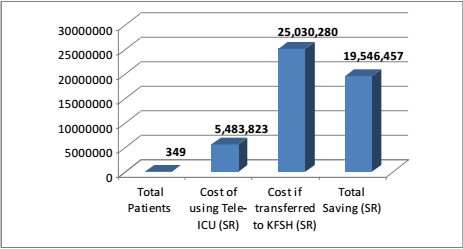

Tele-ICU is a video-conferencing facility that allows doctors and nurses to attend to patients who need remote critical care. It is part of the health outreach services offered by KFSHRC (King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre 2013). Using advanced hardware and software tools, this platform allows doctors in remote locations to gain access to professional medical opinions in their places of work, without travelling to KFSHRC. Researchers who have investigated this health outreach program have found that it improves patient outcomes and increases financial savings from transport costs (Ali-Rayes 2014). Nonetheless, the biggest limitation of this outreach program is its availability in areas that are within the e-health network only. The table below represents the costs needed to run the e-health network in the past three years.

Table 4: Cost of running e-Health Network

(Adapted from Ali-Rayes 2014)

The 2010 tele-ICU report appears below

The above diagram shows that the cost of transferring a patient to KFSHRC towers over the cost of operating the tele-ICUs more than five times. This analysis shows there is significant cost savings associated with the use of tele-ICU facilities.

National Surgical Program

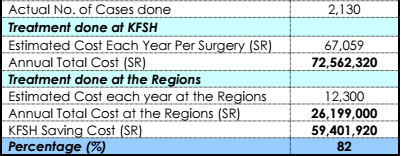

The purpose of introducing the national surgical program, by the KFSHRC, was to provide standard surgical care to patients who could not travel to Riyadh and seek the same services at the main facility (King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre 2013). As part of the outreach program, teams of surgeons travel to different parts of the country with necessary equipments and perform different types of surgeries. Most of them are usually perform sensitive surgeries, such as cardiac surgeries and cancer removal surgeries. Transplant surgeries are also commonly undertaken as part of these outreach programs. After completing these surgeries, the doctors often perform a postoperative round, still under the outreach program, to evaluate the progress of their patients (Ali-Rayes 2014). Annually, KFSHRC undertakes more than 1,000 surgeries under this program (King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre 2013). There are significant cost savings associated with such programs because within the last two years, the surgeries only cost SR 26,199,000 under the health outreach program, as opposed to SR 72,562,320 that they would have cost doctors performed the same surgeries at KFSHRC (Ali-Rayes 2014). The savings associated with the outreach program are therefore close to SR 60,000,000 (Ali-Rayes 2014). The table below shows the associated costs and expenses of undertaking this outreach program

Summary

Comprehensively, the findings shown in the above assessments show significant cost savings for KFSHRC’s health outreach programs. These savings spread across families, the ministry of health and the hospital. The three groups of health outreach programs (polyclinics, tele-ICUs and national surgical programs) also demonstrate the maintenance of health quality standards, even though KFSHRC may provide health services outside the main facility. Timeliness of delivery and the appropriateness of services provided in these outreach programs demonstrate this fact. These evidences show that future cost savings depend on the emphasis on expanding existing outreach programs and the willingness by both private and public authorities to allocate adequate resources to them.

Discussion

One of the objectives of this paper was to investigate the cost-effectiveness of the health outreach programs of KFSHRC. An abstract analysis of our study shows significant savings in medical costs, which are directly proportional to the length of the outreach program. However, this analysis depends on who is undertaking it because it would not always result in cost savings for everybody involved. For example, a health insurer would find it more expensive to pay for cancer screening services as opposed to its associated treatment (Mohamud 2015). The cost of insurance would be even higher if patients undertake frequent screening. Relative to this fact, such a health stakeholder would not fully support a health outreach program.

Nonetheless, regardless of the assumptions made in this paper, the health outreach programs highlighted in this paper demonstrate cost-effectiveness. It increases with the length of screening time because of the effect of discounting which occurs when patients incur costs at present and enjoy the benefits later. Although the findings obtained are sensitive to error rates, we should pay a close attention to the cost of these health outreach programs and their associated savings. For example, when outreach costs decrease because of the expansion of geographical outreach (economies of scale), the cost savings from the program are bound to increase twofold. If we simulate a minimum cost for a cervical cancer-screening program, we find significant changes in the cost-benefit analysis because the attractiveness of each level of the screening process increases threefold. Comprehensively, these findings highlight the evidences obtained from the quantitative analysis of the research questions. The subsection below shows some of the findings obtained from the qualitative aspect of the research.

Benefits of the Outreach Programs

Direct Benefits

The second and fourth chapters of this study have shown that the health outreach programs of KFSHRC offer immense benefits to rural residents and other people who cannot access health services in the hospital’s main facilities. The findings of this paper reveal that the health outreach programs run by KFSHRC are effective because of the cost-saving advantages associated with different interventions. Particularly, this paper has focused on highlighting the reduction of cancer risk factors as possible benefits of these programs. This finding reflects similar findings undertaken by health system research, which highlights the importance of promoting the effective and efficient use of resources to manage cancer cases (Tulchinsky & Varavikovam 2014). This function is important in determining how to allocate health resources in the health sector and how to meet current health needs. Health system research also highlights the neglect of primary care as an important aspect of cancer management cases, because, similar to the arguments advanced in this research, emphasis on hospital care at the expense of primary care is still a common problem in Saudi Arabia and other developing countries (Tulchinsky & Varavikovam 2014). In such countries, a high allocation of health resources goes to acute care at the expense of primary care, which could help in early detection of cancer or improving cancer-screening services. This imbalance partly explains the high mortality rates associated with cancer cases in Saudi Arabia.

The findings of this paper have also shown that KFSHRC’s outreach programs strive to eliminate delays in the access to health care services and promote the speedy delivery of health care to rural communities. People who live in these rural areas benefit from such programs because they gain access to health services that would have cost them a lot of money to access. Supported by a national policy from the state or federal government, the scope of such benefits could spread further than they already do. Relative to this fact, the World Health Organization (2011) says such outreach programs should not compete with established health workers and their facilities in urban areas because they cannot cover the geographical regions served by established facilities.

It also cautions that the level of health coverage may vary the type of care offered to these residents and their quality. Relative to this challenge, the health agency recommends the need to include doctors in outreach programs when they are located in urban centers because they rarely venture out of this space (World Health Organization 2011). Their increased rotation across different mobile clinics would spread their skills and make it easier for people to access specialized care.

Indirect Benefits

Some of the indirect benefits associated with KFSHRC’s outreach programs include capacity enhancements in rural-based health facilities and the indirect training of health personnel who work in these communities (Hoffman 2012). Such benefits are real because most of the health care professionals in rural areas suffer from professional isolation (Hoffman 2012). The World Health Organization (2011) believes that this problem is more profound in developing countries located in Sub-Saharan Africa and some parts of Asia because most of the population lives in rural areas. The trend towards urbanization in most of these countries would increasingly reduce the efficacy of health outreach programs. In this regard, it is important to bolster cooperation between health workers working in urban areas and those working in the rural areas.

Challenges of Outreach Services

Most of the outreach services undertaken by KFSHRC occur on a small scale. Their low levels of documentation also highlight some inherent challenges associated with their implementation because some people consider them acts of charity or part of the national health care delivery system (World Health Organization 2011). Therefore, most of the information available about such initiatives is scarce and descriptive. Part of the problem is the little attention paid to health communication which makes it difficult to understand the full scope of some of these outreach services including their impact on their community. Fully assessing outreach services, in terms of their health outcomes, is critical in developing efficient strategies for creating positive impacts from existing outreach programs.

Program sustainability is also another challenge associated with the implementation of KFSHRC’s outreach programs. The hospital has implemented some of its programs on uneven and irregular schedules, which are prone to cases of specialized doctors failing to visit (Ali-Rayes 2014). The lack of commitment at national and local levels undermines the potential efficacy of some of these programs. The World Health Organization (2011) suggests that this problem could be solved when these outreach programs are included as part of the national policy on health. This strategy would increase the commitment of health personnel towards making sure these programs work.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Many public health hospitals serve the Saudi Arabian health care system. However, most of them cannot cater to people who need tertiary health services. The numerous private hospitals in the country cannot do so either. This is why referral hospitals like KFSHRC are important, especially for patients who need critical care or palliative care facilities. The health outreach programs, outlined in this paper, supplement some of these services because they provide critical care services to rural populations. In light of the challenge that exists in catering to the health needs of cancer patients, the provision of critical care services should become part of the country’s primary care services. However, it would take a long time before such a change occurs because many Saudis consider such services as part of “western medicine” and not their authentic medical remedies. This is why health care stakeholders should match the existing culture with the rapidly changing nature of technology. The potential to do so lies in the involvement of many western-trained doctors, from Saudi Arabia, who stand a better chance of integrating Saudi culture in the existing health care system.

Nonetheless, the cancer fight in Saudi Arabia does not end within the boundaries of hospitals. Making a difference in this fight involves offering cancer screening and early detection services to the people. In such initiatives, the hospital should inform people about the causes of cancer, its potential risk factors, and the steps they could take to minimize their potential exposure. In this regard, hospitals should provide residents with information about healthy behaviors and lifestyle factors that could play a role in the minimization of cancer risks among the population. Similarly, health practitioners should help to test people and help them receive palliative care. KFSHRC’s outreach programs have exemplified these benefits because they have educated the public about cancer management and prevention. They have also raised the level of awareness about existing health services to manage it. In this regard, they have had a positive impact on Saudi Arabia.

Future for Growth and Improvement

Stakeholder Involvement

Different factors could influence the growth and impact of KFSHRC’s health outreach programs. Particularly, support from political bodies, and economic agencies are crucial to the success of such programs if they should have a greater impact than they already have (Mufti 2007). Social issues, environmental issues, and technological advancements are also likely to influence this trend (World Health Organization 2011). For example, the adoption of new technological applications on the e-health platform depends on the cooperation of all stakeholders, including patients, physicians, nurses, regulatory bodies, telecommunication societies, and medical societies.

Public-Private Partnerships

Part of the problem facing the Saudi Arabian health care system is the lack of enough tertiary health care facilities. The demand for such health services outstrips the country’s capability to offer them (Mohamud 2015). This is why KFSHRC is struggling to keep up with the demand for such services by introducing health outreach programs in rural communities. To alleviate this problem, the country needs to invest more in expanding its health infrastructure to keep up with this demand. Primarily, this strategy involves building more hospitals. In the long term, the state could upgrade existing health facilities and equip them with modern facilities to manage current health challenges. Already, some stakeholders in both government and private circles are thinking about this strategy. Charity organizations have been on the forefront in embracing this strategy because in August 2015, the Eman Charity Organization for Cancer announced that it would collaborate with the Saudi Ministry of Finance to construct a medical complex that would provide free cancer screening services (Alawi 2015). The project should take three years before people can access its services and it “will be located on Jeddah-Madinah highway. It will have three towers with a total area of 5,000 square meters. The total cost of the project is SR147 million: SR50 million for the first phase and SR97 for the second” (Alawi 2015, p. 3). Key hallmarks of the project will be the inclusion of state-of-the-art technology for cancer diagnosis and screening services. The facility would also include several units for daily treatment of patients who suffer from most types of cancers (Alawi 2015). The announcement of this project and its expected short completion time is testament to the potential that exists in addressing the problem of an insufficient supply of referral facilities if private and public health agencies collaborate to improve the country’s health infrastructure.

Increased Education and Awareness

This paper partly shows that part of the reason for the high incidence of cancer in Saudi Arabia is the failure of the health system to bridge the gap between knowledge and practice at different levels. To address this challenge, health stakeholders should put greater focus on promoting cancer education at community levels. The purpose of doing so is to change people’s attitudes towards screening and to eliminate the misconceptions about the disease and its associated risk factors. This recommendation stems from studies that have shown that the emphasis on prevention could greatly reduce the incidence of certain types of cancers, such as breast and cervical cancers (Mohamud 2015; Gorin 2013). However, there should be a quality primary care system, free from economic and cultural barriers, for this strategy to work. There should also be an effective referral system for basic surgical and radiotherapy treatments. Most of these proposals would not work if there were no government support, in terms of policy and resource support, to ensure the health services provided are of high standards. Such support will be important in integrating the fragmented provision of care for non-communicable diseases through proper planning, implementation and monitoring of different health systems. However, the provision of quality care in the primary care setting largely depends on the availability of skilled personnel. They also need to have good supervision and dependable structures to refer patients to tertiary care if there is a need to do so. However, the primary care setting would not meet the needs of people suffering from non-communicable diseases if they do not have the resources to do so. For example, they need to have adequate medication and technological resources to offer palliative care and other health care services that may be appropriate for patients. Relative to these factors, it is important to focus on the provision of a universal care model for improving patient-centered primary care to provide quality health care for people who suffer from these diseases. The development of future strategic plans for the management of non-communicable diseases, such as cancer, is similarly important in supporting these efforts because it would improve early detection efforts and cancer control. Indeed, the role of the primary care setting in screening high-risk patients is critical to the improvement of cancer screening and prevention efforts (Mohamud 2015; Gorin 2013). In this regard, health agencies should focus on investing in the primary health care setting as the first point of contact between patients and the health care system because this is the most important place where health practitioners could effectively undertake cancer screening. Collectively, the implementation of these recommendations should improve the positive impact that KFSHRC’s health outreach programs already have.

References

Alawi, I 2015, Saudi medical complex to offer free treatment for cancer patients. Web.

Ali-Rayes, A 2013, Health Outreach Services Department. Web.

Ali-Rayes, A 2014, Helath Outreach in Saudi Arabia: Case Study. Web.

Baird, G & Wright, N 2006, ‘Poor access to care: rural health deprivation’, Br J Gen Pract, vol. 56, no. 529, pp. 567–568.

Bergeron, B 2013, Developing a Data Warehouse for the Healthcare Enterprise: Lessons from the Trenches, HIMSS, New York.

Creswell, J & Clark, V 2011, Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, SAGE, London.

Gorin, S 2013, Prevention Practice in Primary Care, OUP USA, New York.

Greene, J 2007, Mixed Methods in Social Inquiry, John Wiley & Sons, London.

Hair, J 2015, Essentials of Business Research Methods, M.E. Sharpe, New York.

Helen Ziegler and Associates 2015, King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre, Riyadh. Web.

Hesse-Biber, S 2010, Mixed Methods Research: Merging Theory with Practice, Guilford Press, New York.

Hoffman, B 2012, Health Care for Some: Rights and Rationing in the United States Since 1930, University of Chicago Press, Illinois.

King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre 2013, Our Hospitals. Web.

Knaul, F 2012, Closing the Cancer Divide, Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Meade, C & Menard, J 2007, ‘Impacting Health Disparities Through Community Outreach: Utilizing the CLEAN Look (Culture, Literacy, Education, Assessment, and Networking)’, Cancer Control Journal, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 70-77.

Mohamud, S 2015, Transforming Public Health in Developing Nations, IGI Global, New York.

Mufti, M 2007, Healthcare Development Strategies in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Springer Science & Business Media, New York.

Onwuegbuzie, A & Combs, J 2011, ‘Data Analysis in Mixed Research: A Primer’, International Journal of Education, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 1-25.

Rocha, A, Correia, A, Costanzo, S & Reis, L 2015, New Contributions in Information Systems and Technologies, Springer, New York.

Rose, M 2013, Oncology in Primary Care, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, London.

Saudi Health Council 2014, Cancer Incidence Report Saudi Arabia. Web.

Sebai, Z 2014, Health in Saudi Arabia, Partridge Publishing, Singapore.

Tulchinsky, T & Varavikovam, E 2014, The New Public Health, Academic Press, New York.

World Health Organization 2011, Increasing Access to Health Workers in Rural and remote Areas. Web.

Younge, D, Moreau, P, Ezzat, A & Gray, A 1997, ‘Communicating with cancer patients in Saudi Arabia’, Ann N Y Acad Sci, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 309-16.