Topic and Background

Medication errors are known to affect the quality and robustness of healthcare systems (NCCMERP, 2018). The National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention describes a medication error as ” any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while it is in the control of the health care professional, patient or consumer” (NCCMERP, 2018, para. 1). Comparatively, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2019) defines a medication error as “an act of commission or omission at any step along the pathway that begins when a clinician prescribes medication and ends when the patient actually receives the medication” (para. 1). Although there are varying descriptions of medication errors, the general understanding is that they often occur through unintentional acts of omission or commission by medical personnel that may cause harm to patients (Mostafaei et al., 2014). Indeed, most medication errors emerge from challenges associated with medical practice or healthcare products and systems (Alsaleh, Abahussain, Altabaa, Al-Bazzaz, & Almandil, 2018).

Medication errors significantly affect patients’ welfare. They could have vast effects on families and communities but at an individual level, they could cause disabilities and death. For example, Cousins (2018) documents a case where a 5-year-old died after being prescribed epilepsy medicine that was seven times higher than the required amount. There is also another case where a seven-month-old child died in the United Kingdom (UK) after doctors prescribed an anti-epilepsy dosage that was 12 times higher than the required amount (Cousins, 2018). The incident happened in east London and the healthcare practitioners who were responsible for the mistake were suspended and prevented from future administration of medicine (Cousins, 2018).

Nurses have also been singled out as perpetrators of the vice because Cousins (2018) reported an incident where a mother of four children died after receiving a dosage that was ten times higher than the required limit. The patient died from a heart attack in Birmingham after an inquest found out that the dosage given to her had excess potassium chloride (Cousins, 2018). The effects of such medication errors have also been reported among cancer patients because two people recently died from an overdose of medication given to them to combat the side effects of cancer medication (Cousins, 2018). The patients were given up to five times the required dosage (Cousins, 2018). A diabetic patient also died after nurses administered a dosage of insulin that was ten times higher than the required limit. The 80-year-old patient died only hours after receiving the medication (Cousins, 2018).

The American Society of Hospital Pharmacists suggests that the actual incidence of medication errors is unknown because different jurisdictions have varied views of the concept (Alsaleh et al., 2018). Similarly, the application of varied methodologies in the computation of medication errors and the use of different study populations to account for the same problem have also influenced how experts determine the incidence of medication errors (Abdel-Latif, 2016). These variations notwithstanding, some Indian-based researchers estimate that there is a 25% prevalence of medication errors in hospitals, while others suspect that it is about 15% (Patel, Desai, Shah, Patel, & Gandhi, 2016). Nonetheless, it is important to note that a significant percentage of medication errors are undetected because of underreporting by healthcare personnel and the apparent failure of some errors to affect patients’ lives (Jember, Hailu, Messele, Demeke, & Hassen, 2018).

Medication errors stem from weaknesses in healthcare systems but the sources of the problem are varied. For example, drug-to-drug interactions, which often occur when two types of medications are administered and one of them reduces the efficacy of another, is considered a source of medication errors (Assiri et al., 2018). In fact, statistics project that this type of problem accounts for between 6% and 30% of such mistakes (Assiri et al., 2018). Other causes of medication errors are self-medication and poor communication between healthcare practitioners and their patients (Farzi, Irajpour, Saghaei, & Ravaghi, 2017). Patients are also catalysts of medication errors when they demand different treatments for each type of symptom or complication they have (Assiri et al., 2018). Unethical drug promotions and inducements have also been linked with medication errors (Patel et al., 2016).

Medication errors commonly occur during the processes of prescribing, administering or dispensing medications. Although such errors are fewer compared to other types of medical cases, such as prescription medicine misuse, they could have serious financial, emotional and physical harm to affected people (Alsaidan, Portlock, Aljadhey, Shebl, & Franklin, 2018). According to Alsaleh et al. (2018), medication errors are ranked as the eighth leading causes of mortality in the United States (US). These errors are also said to cause between 44,000 and 98,000 deaths annually (Alsaleh et al., 2018). These deaths are often deemed preventable, but only 28% of adverse drug effects (ADE) are deemed as so. These adverse drug events are considered to be “injuries resulting from medical interventions related to a drug” (Alsaleh et al., 2018, p. 2). Relative to the above assertion, Freund et al. (2015) say that medication errors occur in about 10% of all visits to the emergency department in the US. In France, the rate is higher because it is estimated that medication errors occur in about 42% of emergency room visits (Freund et al., 2015). At the same time, 10% of these errors are estimated to cause ADE (Freund et al., 2015).

Independent reports show that medication errors cost about $42 billion (UBM, 2018). If these figures are statistically analysed relative to other financial indices in the healthcare sector, the UBM (2018) says that medication errors account for about 1% of the global healthcare spending. The incidence of medical errors is probably higher because many healthcare professionals fail to disclose their occurrence. For example, Hs and Rashid (2017) say that only 10% of medical professionals intend to disclose medical errors when they happen. This finding means that up to 90% of healthcare professionals are unwilling to disclose such errors, especially if they happen under their watch.

Medication errors could cause adverse events but when they are intercepted earlier, they have little potential for harm (Rishoej, Almarsdóttir, Thybo, Hallas, & Juel, 2018). Medication events that cause harm are either preventable or non-preventable. A report prepared by Cousins (2018) investigated these types of medication errors and established that prescription and dispensing errors were the most commonly reported. Relative to this discussion, it was also established that one out of 20 incidents of medical errors was medication-related, while 1/550 incidents reviewed had a serious implication on patient safety (Cousins, 2018). Similarly, out of 1 billion medical errors analysed in 2012, 1.8 million of them were medication-related and had serious implications on patient safety (Cousins, 2018). Prescription errors are most common because they affect 7% of medication orders and 2% of patient days (Cousins, 2018). In addition, 50% of hospital admissions are linked to this problem (Cousins, 2018). This study explores how to improve medication errors in a Kuwaiti government hospital through training and vigilance. The section below reviews what other researchers have said about this topic.

Review of Literature

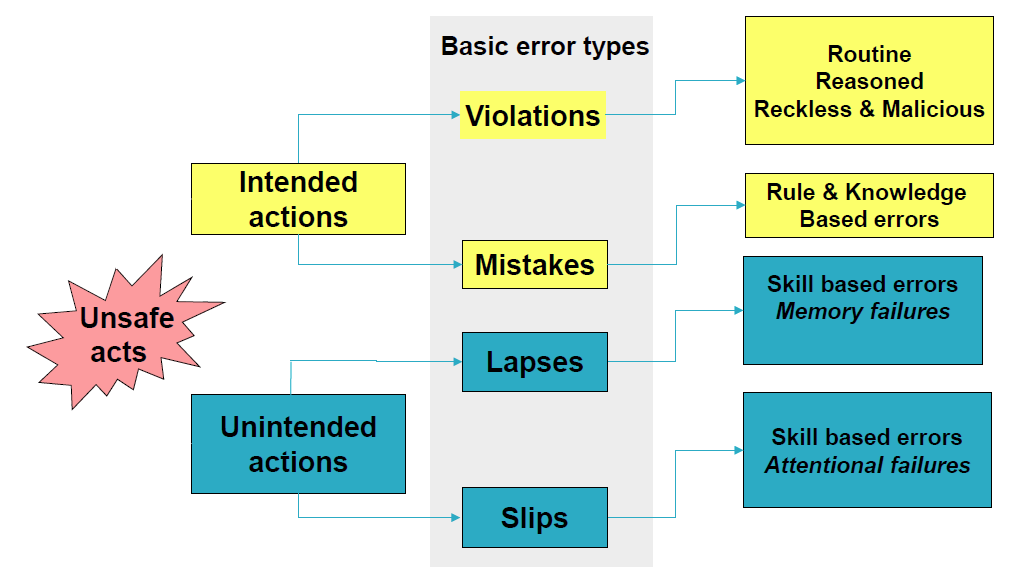

The occurrence of medication errors has been associated with human factors, such as the lack of vigilance and laziness (Yousef & Yousef, 2017). Figure 1 below shows that human error can lead to either intended or unintended actions, which cause medication errors (Cousins, 2018). Intended actions include basic error types such as violations and mistakes, while unintended actions often amount to slips and lapses in judgement, which lead to the improper administration of medicine (Cousins, 2018). Lapses commonly lead to skill-based errors or memory failures, while slip-ups are associated with skill-based errors that stem from the failure of healthcare professionals to be attentive in their work (Chalasani, Ramesh, & Gurumurthy, 2018). Comparatively, violations are linked to routine reasons and actions, which are often associated with reckless and malicious behaviours of healthcare service professionals (Cousins, 2018). Comparatively, mistakes lead to rule and knowledge-based errors. Figure 1 below depicts the broader linkages among these types of errors.

The occurrence of medication errors has been linked to several operational models. One of them is the Swiss cheese model, which suggests that some medication errors are products of active failures, while others occur because of latent conditions in the healthcare environment (Cousins, 2018). This analogy draws strong similarities with the views of researchers who argue that most medication errors are products of human factors and systemic weaknesses in the provision of healthcare services (Yousef & Yousef, 2017).

Medical Error Reporting

The importance of medication error reporting is at the core of efforts to curb the vice because it is only through accurate statistics that stakeholders can effectively address the problem. In a study that investigated the importance of medication error reporting in improving the quality of care, it was reported that most medical errors (38%) occur during the prescription stage (Elden & Ismail, 2015). The second major cause of medical errors was the administration of medicine because about 20.9% of medical errors occur during this stage (Elden & Ismail, 2015). Out of all these mistakes, 45% affected patients and only 1.4% of them were harmless (Elden & Ismail, 2015). To address these medical issues, Elden and Ismail (2015) suggested that healthcare administrators need to employ a ward-based clinical pharmacist to detect medication errors. The researchers also highlighted the need to re-evaluate systemic errors to decrease the susceptibility of organisations to these errors (Elden & Ismail, 2015). These findings were developed after the researchers conducted their investigation in a 177-bed capacity healthcare facility (Elden & Ismail, 2015).

The unwillingness of medical professionals to disclose medical errors has been identified as an impediment to the effective management of the problem because it is not possible to act on them when their existence is not acknowledged in the first place. Consequently, researchers have proposed that an environment of transparency should be nurtured in healthcare organisations to curb this practice. For example, a study by Johnson, Adkinson, and Chung (2014) which evaluated the occurrence of medication errors among pharmacists acknowledged that many of them are unwilling to disclose such errors because of the fear of looking incompetent. Consequently, they proposed that a culture of transparency should be created to prevent the practice (Johnson et al., 2014). The researchers also pointed out the need to train healthcare professionals about the management of medication errors by providing them with a guide that stipulates how to do so (Johnson et al., 2014). They also believe that this recommendation would promote ethically responsible medical care practices (Johnson et al., 2014).

A UAE-based study on medication errors investigated the link between the need to report medical errors and their severity. After sampling the views of 106 respondents, it was established that physician training on medical errors needs to start during medical school and not on the job (Zaghloul, Rahman, & Abou, 2016). Notably, the researchers observed that this strategy would reduce apprehension among physicians, which leads to the occurrence of medication errors (Zaghloul et al., 2016). They also suggested that such a strategy would help them to better disclose mistakes made in the process of dispensing medicine (Zaghloul et al., 2016).

Concerning the issue of reporting, Kang, Park, Oh and Lee (2017) say that the most important item to report is “near misses.” These mistakes refer to the potential for medication errors to occur. The researchers obtained their data after surveying 245 pharmacists (Kang et al., 2017). The respondents were asked to explain near misses they may have had during the process of drug dispensing, making prescriptions or during administration. The researchers found out that there were about five near misses reported every month (Kang et al., 2017). Most of them stemmed from the process of prescribing medicine. Consequently, the researchers proposed that health facilities should have proper reporting structures to enable pharmacists to report their mistakes (Kang et al., 2017). Nonetheless, they recognised that the lack of harm in the occurrence of some medication errors deterred pharmacists from reporting the errors (Kang et al., 2017).

Researchers have linked the failure to report the occurrence of medication errors with the attitudes and beliefs held by healthcare practitioners about such mistakes. For example, a Finnish study authored by Nevalainen, Kuikka, and Pitkälä (2014) showed that younger and older medical professionals have different perceptions of medication errors because younger professionals were more cognizant of this challenge compared to their older counterparts. In other words, younger professionals were more fearful of committing such mistakes and reported them if they happened (Nevalainen et al., 2014). The experience of medical practitioners was also identified as a moderating variable to the occurrence of medication errors because more experienced professionals were less likely to commit such mistakes compared to younger professionals (Nevalainen et al., 2014). For example, the study found that older and more experienced medical professionals were more likely to apologise for committing an error compared to their younger counterparts (Nevalainen et al., 2014). Older professionals were also reported to have a higher tolerance for uncertainty compared to practitioners who had fewer experiences (Nevalainen et al., 2014). Therefore, it was deduced that experience helped younger professionals to cope with medication errors. Therefore, Nevalainen et al. (2014) emphasised the need to look for ways to empower professionals to manage these errors by influencing their coping strategies. Data used to come up with these findings were obtained through self-reported questionnaires, which were answered by 165 medical professionals (Nevalainen et al., 2014).

Causes of Medical Errors

Another area of discussion that has been explored by researchers is the cause of medical errors. For example, Tawfik et al. (2018) explored the role of physician burnout, wellbeing, and work structures in the occurrence of medication errors and found out that 77% of such mistakes were attributed to physician burnout (Tawfik et al., 2018). Generally, the findings pointed out that physician burn out and a safety culture all shared a relationship with medication errors (independently). These insights were obtained after sampling the views of 6,695 pharmacists through a population-based survey (Tawfik et al., 2018).

A different study authored by Kalmbach, Arnedt, Song, Guille, and Sen (2017) pointed out that poor quality sleep among medical professionals was linked to the occurrence of medication errors. Long working hours, mood swings and work performance were also associated with the occurrence of such errors (Kalmbach et al., 2017). These findings were developed after sampling the views of 1,215 medical interns (Kalmbach et al., 2017). The respondents also said that within the first few months of internship, they were more susceptible to depression, especially based on poor sleep patterns (Kalmbach et al., 2017). Elevated risks of medication errors were also reported among health practitioners who slept less than 6 hours or those who worked more than 70 hours (Kalmbach et al., 2017). Overall, the study pointed out that sleep disturbance and its associated irregularities contributed to a heightened risk of medication errors.

A different study authored by Trockel et al. (2017) sampled the views of 250 resident and practising physicians regarding medication errors and their relation with burnout and professional fulfilment and established that both variables increased the risk of such mistakes. Comparatively, general statistics about physician burnout suggest that up to 50% of physicians are fatigued (Tawfik et al., 2018). In fact, excessive fatigue is estimated to affect up to 45% of these professionals (Tawfik et al., 2018). These statistics explain why the suicide rate among them is between three to five times higher than in the general population (Tawfik et al., 2018).

Although several studies highlighted above have mentioned the role of physician burnouts, fatigue and lack of adequate sleep as catalysts of medication errors, a study by Mankaka, Waeber and Gachoud (2014) suggests that the characteristics of health practitioners could also affect their risk of occurring. The role of gender in determining the occurrence of such mistakes has also been highlighted, but the results have been conflicting. Nonetheless, the researchers explain that part of the reason why most medical practitioners fail to disclose medical errors is the negative experiences they have after doing so (Mankaka et al., 2014). This view is linked with poor coping mechanisms because most of them are unable to effectively manage the repercussions of committing an error. At the same time, the researchers noted that there is a sexist attitude among many male physicians who make female colleagues fearful of reporting medication errors (Mankaka et al., 2014). These findings were developed after investigating the views of 57 female residents working in a Swiss University Hospital (Mankaka et al., 2014).

Role of Patient Safety Culture in the Occurrence of Medication Errors

Some research studies that have investigated medical errors in Kuwait have focused on the role of creating a patient safety culture to curb the problem. Alsaleh et al. (2018) define patient safety as “the freedom from accidental injuries during the course of medical care; activities to avoid, prevent, or correct adverse outcomes which may result from the delivery of healthcare” (p. 2). In line with studies that have focused on emphasising the role of a patient safety culture in minimising medication errors, a study by Alqattan, Cleland and Morrison (2018) highlighted the role of creating a strong patient safety culture to minimise medical errors. This recommendation was developed after evaluating the role of patient care in a secondary care setting (Alqattan et al., 2018). Information was obtained after sampling the views of 1,008 physicians who worked in Kuwaiti public hospitals (Alqattan et al., 2018).

Three tenets of the patient safety culture were identified to be the most important in reducing medication errors. They included the non-punitive response to medication errors, staffing and communication openness (Alqattan et al., 2018). Teamwork was also established as another key tenet of patient culture, which influenced the occurrence of such errors (Alqattan et al., 2018). Overall, Alqattan et al. (2018) pointed out that many Kuwaiti nationals had a low perception of a strong patient safety culture in their institutions. However, the same researchers pointed out that patient safety is subject to the demographic characteristics of the respondents sampled, including their countries of origin, education levels, professions and age groups (Alqattan et al., 2018).

Ghobashi, El-ragehy, Mosleh and Al-Doseri (2014) also explained the role of the patient safety culture in reducing medication errors because they pointed out that such a culture is instrumental in reducing human and systemic weaknesses in the provision of healthcare services. The researchers also argued that patient safety is critical to the improvement of patient safety (Ghobashi et al., 2014). These views were obtained after the researchers sampled the views of 369 employees of four Kuwaiti public hospitals (Ghobashi et al., 2014). The researchers’ data collection method was based on the descriptive design and 74.59% of the respondents returned the questionnaires (Ghobashi et al., 2014). Overall, according to the results of the study, patient safety in Kuwait was weak. Consequently, the researchers recommended the need to integrate a safety culture in organisational policies (Ghobashi et al., 2014). Particularly, they emphasised the need to review the bioethical component of medical errors to achieve this goal. At the same time, they suggested the need to review training procedures for health workers and emphasised the importance of creating a strong team attitude to support skilful organisational learning (Ghobashi et al., 2014).

The need to review safety cultures in hospitals (as a strategy of managing medication errors) has been supported by several global healthcare organisations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the National Patient Safety Foundation (NPSF) (Elmontsri, Almashrafi, Banarsee, & Majeed, 2017; Ali et al., 2018). Other global institutions that hold the same position include the Joint Commission International (JCI) and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) (Ali et al., 2018).

Proposed Remedies for Addressing Medication Errors

An Iran-based study authored by Freund et al. (2015) sought to investigate effective ways of addressing medication errors by examining whether systematic cross-checking by an emergency physician in a critical care environment would reduce their incidence. It was established that the incidence of such errors could decline if more physicians were assigned the responsibility of crosschecking medical operations across different care settings (Freund et al., 2015). Some observers have proposed the need to educate patients about medications as a strategy to minimise associated errors because many people are unaware of the implications or effects of such medicines on their bodies (Zaree, Nazari, Asghary, & Alinia, 2017). For example, patients should be educated about the colour and names of their drugs so that they report any anomalies if they occur. Educating them about the drugs they take should also enable them to understand what the medicines are meant to do and their possible side effects. Therefore, by educating patients about their treatments, they would better understand the need to alert their doctors about changes in the administration of their medication.

The World Health Organization (2016) advocates for a review of patient safety standards as one of the ways of managing medication errors. It presupposes that healthcare facilities need to adopt a wide range of actions that should involve performance improvements, and environmental safety risk awareness to address this problem (World Health Organization, 2016). Their recommendations also emphasise the safe use of medicine and the promotion of equipment safety as other techniques that should be employed to minimise incidents of medication errors.

A regional evaluation of healthcare systems in the European Union, which was aimed at reducing the incidents of medication errors, also recommended the need to enhance health system’s performance to protect patients from experiencing medication errors (Cousins, 2018). The European Commission proposed that member states should adopt this recommendation by preventing adverse events (Cousins, 2018). Nonetheless, the necessity to promote patient safety is highlighted not only as a technique for reducing the incidents of medication errors but also a fundamental principle of all healthcare systems. All 28-member states of the European Commission have also been encouraged to pay close attention to the need to establish a culture of patient safety and the need to strengthen evidence-based practices in the management of medication errors (Cousins, 2018). Improved monitoring and using advanced medical equipment and technology have also been proposed as possible strategies to mitigate the issue (Cousins, 2018).

In line with the above recommendations, proposals have also been made for the global healthcare sector to learn from other industries, which have a high safety standard, such as the airline, nuclear, and oil and gas sectors (Cousins, 2018). The use of common risk reduction measures and auditing are other solutions that medical practitioners have pursued in the past (Ayani et al., 2016). Broadly, Alsaleh et al. (2018) say that medical errors are preventable and pharmacists could curb 50% of the cases if they were more vigilant with their work. This proposal is also linked with recommendations made by other researchers, which suggest that pharmacists play a critical role in the improvement of patient safety and quality of care (Ayani et al., 2016).

Nonetheless, Alsaleh et al. (2018) say that a culture of safety is at the centre of efforts to improve the quality of care. The focus on a safety culture is not new to the research field because, as far back as 1999, the Institute of Medicine recommended that institutional cultures should be re-examined for purposes of advancing medical services (Alsaleh et al., 2018). Broadly, the safety culture represents the group and individual perceptions of medication errors based on their attitudes and values towards the problem.

Terms and Scope of Topic

Terms

- Adverse Drug Events (ADE) – An injury that a patient suffers because of a medication error

- Computerised systems – Use of information technology tools to undertake health functions

- US – United States

- UK – United Kingdom

Scope of Topic

The scope of this study is limited to Kuwait. Therefore, data that will be collected will be sourced from respondents who are in the country. The implication of this data collection method is that the information that will be gathered in the study will be exclusive to the medical practices adopted in the Middle East nation. The scope of this study will also be limited to public hospitals. In other words, information will only be sourced from respondents who work in Kuwaiti public health facilities. Therefore, the medical practices adopted in private hospitals in the country would have no bearing on the research findings.

Outline of Current Situation

The Kuwaiti human rights society has registered its concerns regarding the rising cases of medical errors in the country (ATK, 2018). They attribute the problem to medical negligence (ATK, 2018). In line with these concerns, the Criminal Evidence General Department, which is domiciled in the country’s interior ministry, reported that 450 incidences of medical errors are reported monthly (ATK, 2018). One such incident involved the discharging of a patient who had suffered internal bleeding from an accident by a Kuwaiti doctor who had ruled that internal bleeding had been contained. The patient died because of the error.

In a study to examine the culture of patient safety in Kuwaiti hospitals, Alsaleh et al. (2018) reported that patient safety was a priority in most of the hospitals sampled. The investigation was conducted after sampling the views of 255 community pharmacists working in Kuwaiti public hospitals (Alsaleh et al., 2018). The study also emphasised the need to understand the perspective of community pharmacists regarding a culture of safety in Kuwaiti hospitals because it is instrumental in reducing medication errors (Alsaleh et al., 2018). The study also highlighted the need to improve staffing requirements and reduce work pressures for medical personnel working in these Kuwaiti hospitals.

A different study authored by Ali, Ibrahem, Al Mudaf, Al Fadalah, Jamal and El-Jardali (2018) which investigated the impact of safety culture on medication errors in Kuwait also pointed out that this culture was integral in improving the quality of medical services in the country. Generally, a safety culture has been linked with the actions of hospitals to promote a culture of safety in the Middle East nation. Nonetheless, the management of medication errors in Kuwait has been linked with the need to use evidence-based methods when undertaking health tasks. For example, in a study authored by Buabbas, Alsaleh, Al-Shawaf, Abdullah, and Almajran (2018), pharmacists in Kuwait were encouraged to use evidence-based techniques and acquire up-to-date knowledge about their profession to reduce the risk of errors. The researchers notably drew attention to the need to change the attitudes of pharmacists regarding their jobs as a tool for reducing negligence (Buabbas et al., 2018). Qualitative and quantitative analytical techniques were used to assess the views of 176 pharmacists who worked in secondary and tertiary hospitals in Kuwait (Buabbas et al., 2018).

Evaluation of the Current Situation

Advantages

According to Abdullah (2015), one out of ten patients suffers the negative effects of medication errors. This statistic relates to developed countries, such as Germany and the UK but Kuwait is no different because a lot of attention has been directed at the administrative actions taken by health practitioners as a source of medication errors. A recent report authored by Abdullah (2015) showed that many victims of medication errors in Kuwait suffered physical pain, which manifested as kidney failure and disabilities. Part of the problem has been the systemic failures within Kuwaiti hospitals, which allow medical practitioners such as trainee doctors to conduct complex medical procedures. Therefore, several stakeholders in the Kuwaiti healthcare sector, including nurses and pharmacists, have identified medication errors as a systemic problem (Ali et al., 2018). Their discussions have led experts to recommend the need to train and educate nursing professionals about strategies to minimise them (Krzyzaniak & Bajorek, 2016). Generally, their proposals have been aimed at promoting medication management diligence as a tool for addressing this problem.

Advancements in information technology have been touted as a strategy for addressing this challenge (Hernandez et al., 2015). Particularly, the use of information technology tools in decision-making processes has been highlighted as a technique for reducing human errors that eventually lead to medication errors (Smith et al., 2015). Some associated systemic weaknesses of the healthcare system, such as the failure to act on information generated from laboratory tests, have also been touted as problems that could be addressed at source through information technology advancements (Nuckols et al., 2014). They affect the operations of different stakeholders in the healthcare sector, including patients, healthcare professionals, and institutions. These stakeholders have registered different effects from these medical errors. Therefore, there is no proper framework for implementing proposed strategies for minimising medication errors because of a divide between knowing what needs to be done and actually doing it. Based on this gap, it is important to conceptualise IT management systems as key components of a multifaceted strategy of preventing medical errors in Kuwaiti public hospitals.

The occurrence of medical errors is associated with the different operational practices adopted by healthcare organisations. Particularly, their data management strategies have a significant bearing on the occurrence of medical errors (Chiampas, Kim, & Badowski, 2015). For example, some healthcare facilities use software to prescribe medicine, while others use paper-based prescribing techniques (Nguyen, Nguyen, van den Heuvel, Haaijer-Ruskamp, & Taxis, 2015). Error detection is undertaken different by various organisations. However, common methods that are associated with it include chart reviews and software-enabled monitoring techniques. Traditional methods include observation, incident reporting and patient feedback (Bolandianbafghi, Salimi, Rassouli, Faraji, & Sarebanhassanabadi, 2017). Effective reporting has been touted as a common method for tackling medication errors because it acts as a trigger warning to alert medical practitioners to correct an anomaly before it has a significant effect on patients. Here, retroactive and proactive tools have been used in error detection. For example, different organisations have used audits as a retroactive tool of error detection and monitoring (Nguyen, Mosel, & Grzeskowiak, 2017). Nonetheless, it is important to consider auditing as an educational activity aimed at improving individual or team performance.

Information technology tools have become more commonly accepted instruments for detecting medication errors compared to other paper-based solutions used in the past. The use of software to curb medical errors is the first step toward the improvement of patient safety. For example, the computerised physician order entry technique has been used to prevent medication errors with a high rate of success (Cho, Park, Choi, Hwang, & Bates, 2014). The same is true for automated dispensing cabinets and bedside barcoding tools because both techniques have similarly reported a high rate of success in reducing medical errors (Nguyen et al., 2017). Stated differently, these IT-based techniques could potentially yield cost savings of up to 88 billion in ten years (Nguyen et al., 2017). At the same time, it has been established that hospitals, which use the above-mentioned techniques to reduce medical errors, have reported lower mortality rates and fewer complications (Cho et al., 2014). The benefits associated with software-based tools of information processing have been linked with increased capabilities of IT-based tools to improve access to information and establish links or patterns with these pieces of information (Cho et al., 2014).

The technological trend underlying the management of medical errors is partly explained by Radley et al. (2014) who highlight the use of computerised provider order entry (CPOE) as a technique for managing medication errors. The research study points out that the CPOE could reduce the incidence of such errors by more than 45%. However, the current use of this technique has only yielded a reduction rate of about 12.5% (Radley et al., 2014). Although the minimisation of medication errors has been established using the CPOE, there is still contention regarding its ability to reduce the harm caused on patients (Radley et al., 2014).

Disadvantages

For a long time, the occurrence of human errors in complex medical systems has been a significant topic of contention for many researchers (Gorgich, Barfroshan, Ghoreishi, & Yaghoobi, 2015). The concern mostly stems from the fact that system failures in complex and sensitive systems could have far-reaching implications on human life. This is why any systematic failure in an airline is often treated with urgency. In the healthcare, sector, the attention on human errors has not been as swift because such errors often affect one person at a time. Nonetheless, the first documented cases of human error occurred in the 1990s and although to err is human, there has been considerable attention directed to the need to minimise their occurrence (Ali et al., 2018). Different countries have addressed such concerns by committing themselves to improve the quality of their health services and inculcating a culture of patient safety in health facilities (Mekonnen, Alhawassi, McLachlan, & Brien, 2017). However, researchers still document several cases where patients are suffering in the hands of negligent medical personnel who prescribe wrong medicines or give wrong dosages to patients, thereby putting their lives in jeopardy (Magal et al., 2017).

Medications are important for the improvement of human health. Therefore, many healthcare facilities offer them. However, an increase in medication use could increase the vulnerability to harm. This problem is further compounded by the complexity of demographic variables such as the increase in the population of elderly patients who have complex medical needs. Additionally, the introduction of new medications increases the risk of harm that patients could endure in the hands of medical personnel (Carayon et al., 2014).

Most pieces of literature that have explored medication errors as a significant issue affecting the healthcare sector have discussed the problem from a hospital setting (Prakash et al., 2014). However, medication errors emerge from different types of clinical problems, which are not only confined within the hospital setting (Westbrook et al., 2015). The different cadres of information and the structure of medical services also have a significant role to play in the occurrence of such errors. This analogy means that the risks and solutions offered in the hospital setting may insufficiently address the problem (Newbould, Le Meur, Goedecke, & Kurz, 2017).

According to Ferracini et al. (2016), medical errors could affect patients in several ways. For example, patients have reported experiencing adverse drug reactions, low-efficiency levels associated with selected treatment methods, and suboptimal patient adherence to treatment regimens (Ferracini et al., 2016). Collectively, these negative outcomes cause a low quality of life for patients. Broadly, the same effects could have a negative effect on the economy and the healthcare system such as increased use of healthcare facilities and an increment in medical costs (Ferracini et al., 2016). In fact, in some jurisdictions, it has been reported that 6%-7% of medical errors are because of medication errors. Two-thirds of these cases are preventable (Ferracini et al., 2016). Elderly patients are especially vulnerable because of their complicated health status and polypharmacy.

Gap

As highlighted in this paper, medication errors are common problems linked with a poor safety culture (Janmano, Chaichanawirote, & Kongkaew, 2018). Particularly, there are many concerns in Middle East countries regarding the role played by a poor safety culture in causing medication errors. Most research studies, which have investigated this matter, have done so from a western perspective (Björkstén, Bergqvist, Andersén-Karlsson, Benson, & Ulfvarson, 2016). In other words, there is little information about the occurrence and management of medication errors among Middle Eastern countries and more specifically in Kuwait. More importantly, there are few studies, which have investigated medication errors among Kuwaiti public hospitals. This study seeks to fill this research gap by addressing medication errors in Kuwaiti government hospitals.

Importance of Research

This study is intended to raise awareness in Kuwait about the need to minimise medication errors and identify the strategies to adopt in accomplishing this goal. Overall, this study will help to inculcate a culture of safety in Kuwaiti public hospitals. This statement should be conceived within the greater understanding that the Kuwaiti government has tried to improve its healthcare systems to provide care to its citizens when they are unwell and to help them stay healthy. This study’s findings will be integral in creating a safe primary care environment for Kuwaiti citizens because primary care is at the centre of the country’s integrated people-centred healthcare system.

Creating a safe primary care environment in Kuwait will also support the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, which are predicated on the promotion of healthy lifestyles and the improvement of community wellbeing (World Health Organization, 2016). Indeed, by reducing medication errors, the primary care environment would become safer. The promotion of a protected primary care environment is paramount to the accomplishment of WHO’s sustainability goals because a majority of healthcare services are provided in this environment (World Health Organization, 2016). Furthermore, the magnitude and nature of harm in the primary care environment could have far-reaching implications if not effectively addressed (Agu et al., 2014). Therefore, the need to reduce harm in this environment is unparalleled. Adopting this strategy would reduce the incidence of avoidable hospitalisations that occur because of medication errors. The incidences of disability and death that are associated with such mistakes could also decline when the problem is effectively tackled.

Lastly, the findings of this research could also be useful in informing country-level strategies for improving systems that influence patient safety and the occurrence of medication errors in Kuwait (Weant, Bailey, & Baker, 2014). Such proposals would be specific to Kuwaiti public hospitals, meaning that they would provide a basis for comparing the country’s performance with those of other jurisdictions to find out better ways of minimising medication errors. The expected outcomes for this study are listed below.

Expected Outcome/ Anticipated Benefits

It is anticipated that the study will develop:

- National no-name-no-blame quality management reporting system to record medication errors and near messes nationally

- National training programme on the use of the developed system and the importance of capturing all errors to feedback into the training system as a lesson learned.

- Compare the number of medication errors incidence before and after in six hospitals as a pilot before producing a report to the department of health for consideration to roll in other government hospitals.

Research Problem

Some researchers have proposed that the reduction of the amount of medication errors in healthcare facilities depends on the willingness of healthcare practitioners to learn from their mistakes (Elmontsri et al., 2017). In other words, the minimisation of medication errors depends on their effective reporting and the need to learn from them. This is why accidents, near misses, and adverse events are often recorded and evaluated to minimise their probability of occurring again (Mohanty et al., 2018). In Kuwait, the same process is adopted but most aspects of the country’s healthcare system are still reliant on traditional benchmarks for reviewing medication errors, such as establishing mortality committees and manually scrutinising cases (Ali et al., 2018). However, these techniques are no longer feasible or reliable because the country’s healthcare system has become more sophisticated.

In addition, many Kuwaiti hospitals have inconsistencies in treatment chart reviews, which also add to medication errors. Furthermore, it is difficult to have a consistent treatment chart if there is no assigned pharmacist in the ward (most Kuwaiti hospitals do not have an assigned treatment pharmacist) (Nanji, Patel, Shaikh, Seger, & Bates, 2016). The use of paper-based outpatient discharge prescriptions in such healthcare facilities is also another cause of medication errors because it is associated with legibility issues, which could cause prescription errors (Ernawati, Lee, & Hughes, 2014). At the same time, medication review is rarely done in Kuwaiti hospitals. Reconciliation on admission is also poorly undertaken, thereby contributing to the occurrence of medication errors. Research studies that have focused on the human resource component of medication errors also suggest that a poor ratio between nurses, doctors, patients, and pharmacists in Kuwait have also contributed to such mistakes because it leads to capacity constraints in the dispensation of healthcare services (Krzyzaniak & Bajorek, 2016).

The use of paper-based methods for dispensing medicine has been criticised for its lack of efficiency in promoting a safe patient safety culture because of its vulnerability to human errors. Consequently, experts have proposed the use of information technology tools for pharmaceutical assessment. Different jurisdictions have adopted this technique based on their unique capabilities. In Kuwait, the use of information technology tools to minimise the incidence of medication errors has also been embraced but resource limitations have made it difficult to effectively use such technologies across all public hospitals. For example, some healthcare facilities lack adequate funds to purchase customised software to support such functions. Therefore, they have to rely on generic IT-based tools to carry out this function but doing so has made it difficult to address local needs associated with the administration of medication. This outcome makes it difficult for such healthcare facilities to undertake their duties, especially because different hospitals use different electronic prescription programs. Therefore, it is important for healthcare administrators to develop software that appeals to their local needs.

The lack of technical skills to use Information technology tools in dispensing medicine has also prevented local hospitals from using electronic prescriptions. This problem is necessitated by the fact that the adoption of some information technology techniques requires advanced knowledge to operate them. The lack of an information technology department in many public hospitals has also complicated the problem because it has made it difficult to maintain such systems in the event that they break down. Therefore, it is common to find healthcare administrators refraining from using such systems because of the lack of capacity to maintain them. Lastly, ineffective organisational cultures also impede some healthcare personnel from adopting IT-based tools to manage medication errors. This limitation stems from the fact that, traditionally, most healthcare functions have been based on manual assessment procedures. The lack of proper training has also made some healthcare personnel hesitant to use IT-based tools because there is no cultural support to aid its adoption.

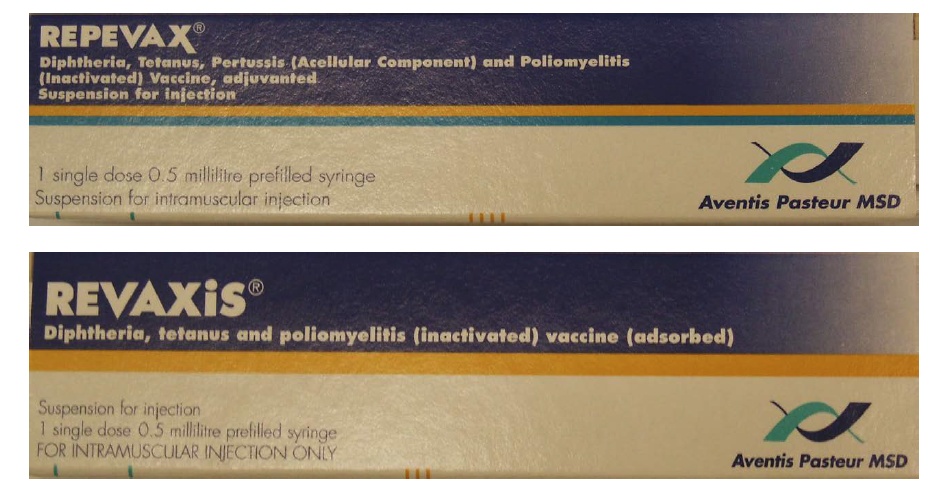

Some medication errors also occur because some medicines sound like or look like each other. Therefore, similarities in brand images cause confusion among healthcare practitioners who may prescribe the wrong drug to a patient. At the same time, it is difficult for a patient to detect such anomalies because of similarities in packaging and colour codes. Some pieces of literature have digressed from the model analysis and presuppose that medication errors occur because of error-prone naming, labelling and packaging. Figure 2 below shows how two types of medications look alike but require different prescriptions.

Based on the research problem identified in this section of the paper, the aim and objectives of this study are highlighted below.

Research Aims and Objectives

Aim

To determine the impact of training and clinical vigilance on medication errors in a government hospital in Kuwait.

Objectives

- To explore effective ways of reporting medication errors in Kuwaiti public hospitals

- To better integrate information technology tools in the management of medication errors in Kuwaiti public hospitals

- To explore the effectiveness of improved training practices on the reduction of medication errors

- To find out the extent that clinical vigilance could minimise medication errors in Kuwaiti public hospitals

Hypothesis

Recording medication errors in a no-name-no-blame system will provide insights on possible causes of medications errors, which will inform health professionals’ training programs to improve clinical vigilance and reduce the frequency of medication errors in Kuwaiti government hospitals.

Order of Information in the Thesis

The thesis will have five key chapters. The first one will be the introduction section, which will provide the background to the study and describe the key direction that will be followed in it. The second chapter will be the literature review section. In this part, a review of previous studies will be done to understand what other researchers have said about the research topic. In this section of the study, any relevant theories or models that could help to answer the research questions will also be highlighted. The third chapter of the paper will explain the methods used to answer the research questions. Some key parts of the methodology, which will be highlighted in the chapter, include the methods used for collecting data and the research design employed. The fourth chapter will review the information gathered from the respondents and relate it to the key research objectives to have a broader understanding of the research findings. The last section will highlight the main findings in the paper in the conclusion section.

Methodology and Title of Dissertation

Title

The title of the dissertation will be “Improving Medication Errors in the Kuwaiti Government Hospitals through Training and Clinical Vigilance.”

Methodology

Data will be collected using a mixed methodology. This research design contains qualitative and quantitative aspects of research, thereby accommodating the collection of two types of data. Data will be collected from three types of professions in the healthcare sector: doctors, nurses and pharmacists. Their views regarding the research topic will be collected using a semi-structured interview. There will be a minimum of 30 participants in the study because each respondent group (based on profession) will have ten respondents. The interviews will form the basis for the development of an online database prototype that will include all parties involved in the dispensation of medicine (storage, prescribing and administration). This prototype will be introduced to the employees of six government hospitals and their feedback assessed for purposes of product improvement. The feedback will also be used to develop a curriculum for educating the employees about how to minimise medication errors. The educational curriculum will then be introduced to the three groups of health practitioners (doctors, nurses and pharmacists). After using the curriculum, the professionals will be asked to give their views on it and the feedback will form the basis for making further improvements on it. These processes will aid in the development of a business case model, which will allow the researcher to design a framework for medication error reduction and submit it to the Ministry of Health in Kuwait for consideration.

Data collection. Information relating to the research will be primarily collected using interviews. Interviews are the selected model of data collection because they are the most preferred mode of collecting information in qualitative studies. The interviews will be open-ended, meaning that the respondents are supposed to develop their answers to the research questions. The interviews will be categorised into different sections. The first one will review the respondents’ demographic information, such as age, educational background and gender. This part of data collection will also include details relating to the professional positions held by the research participants in their respective positions and the duration they have worked in these departments to have a fair assessment of their experience of medication errors. The knowledge held by the research participants regarding medication errors will be assessed in the second section of the interview. Here, the research participants will outline whether they have witnessed or taken part in the occurrence of a medication error. The last part of the interview will probe the respondents’ views regarding potential solutions that could be adopted to manage medication errors.

Recruitment and sampling strategy. This study will sample the views of doctors, pharmacists and nurses who work for a Kuwaiti public hospital. All the research respondents must have at least two years of work experience. The justification for stipulating this work experience is to have respondents who are knowledgeable about medication errors and the importance of safe practices to patient safety. In sum, 90 respondents will be recruited to participate in the study and they will be interviewed in three phases. The justification for sampling them in multiple phases is to establish the level of saturation for the respondents. If the saturation level is not achieved in the first phase, the second one will commence and in that order, saturation will be reached. Using this strategy, the sample size could increase up to 150 respondents.

Study limitations. Respondents’’ attitudes can be a limitation in this study because a poor attitude would lead to suboptimal responses. Particularly, some respondents may think that giving their views about medication errors would be akin to “telling on” each other. Similarly, they may feel like discussions about medical errors could attract judgments about their work. Such fears may cause high withdrawal rates from the study. To mitigate this risk, the respondents would be informed about the goal of undertaking the research, which is to fulfil academic purposes only. In other words, they will be notified that there will be no professional judgments based on their opinions. The level of sincerity in responding to the research questions could also be another limitation of the study because it is difficult for the researcher to gauge the level of sincerity of responses given by the participants.

Data collection. Three stakeholder groups will be consulted as respondents in the study. They are doctors, pharmacists and nurses. These professional groups will form the bulk of the participants because they are knowledgeable about systemic problems influencing the occurrence of medication errors in their departments. Therefore, their knowledge and experience working as healthcare professionals will be instrumental in answering the research questions. The participants will be sourced from a Kuwaiti government hospital and their opinions collected in a survey format.

Data analysis. Data will be analysed qualitatively in four distinct phases. The first one will be the identification of themes, whereby information will be assessed based on how they address the main points of the study. The second stage is representational in nature because the data gathered will be contextualised and represented graphically using multiple tools, such as graphs, bar charts and tables. The third phase will include an explanation of the data obtained because the information, which will be presented in graphs and tables, will be discussed in this part of the analysis. The last stage of data analysis will involve the development of study conclusions. In this part of the analysis, data will be matched with the research objectives and they will be presented as answers to the research questions.

References

Abdel-Latif, M. M. (2016). Knowledge of healthcare professionals about medication errors in hospitals. Journal of Basic and Clinical Pharmacy, 7(3), 87-92.

Abdullah, M. (2015). Handling medical errors. Web.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2019). Medication errors and adverse drug events. Web.

Agu, K. A., Oqua, D., Adeyanju, Z., Isah, M. A., Adesina, A., Ohiaeri, S. I., … Wutoh, A. K. (2014). The incidence and types of medication errors in patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in resource-constrained settings. PloS One, 9(1), 1-10. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0087338

Ali, H., Ibrahem, S. Z., Al Mudaf, B., Al Fadalah, T., Jamal, D., & El-Jardali, F. (2018). Baseline assessment of patient safety culture in public hospitals in Kuwait. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 158. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-2960-x

Alqattan, H., Cleland, M., & Morrison, Z. (2018). An evaluation of patient safety culture in a secondary care setting in Kuwait. Journal of Taibah University Medical Services, 13(3), 272-280.

Alsaidan, J., Portlock, J., Aljadhey, H. S., Shebl, N. A., & Franklin, B. D. (2018). Systematic review of the safety of medication use in inpatient, outpatient and primary care settings in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal, 26(7), 977-1011.

Alsaleh, F. M., Abahussain, E. A., Altabaa, H. H., Al-Bazzaz, M. F., & Almandil, N. B. (2018). Assessment of patient safety culture: A nationwide survey of community pharmacists in Kuwait. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 1-15. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3662-0

Assiri, G. A., Shebl, N. A., Mahmoud, M. A., Aloudah, N., Grant, E., Aljadhey, H., &

Sheikh, A. (2018). What is the epidemiology of medication errors, error-related adverse events and risk factors for errors in adults managed in community care contexts? A systematic review of the international literature. BMJ Open, 8(5), 1-10. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019101

ATK. (2018). KHRS expresses concern over rising cases of medical errors in hospitals. Web.

Ayani, N., Sakuma, M., Morimoto, T., Kikuchi, T., Watanabe, K., Narumoto, J., & Fukui, K. (2016). The epidemiology of adverse drug events and medication errors among psychiatric inpatients in Japan: The JADE study. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 303. doi:10.1186/s12888-016-1009-0

Björkstén, K. S., Bergqvist, M., Andersén-Karlsson, E., Benson, L., & Ulfvarson, J. (2016). Medication errors as malpractice-a qualitative content analysis of 585 medication errors by nurses in Sweden. BMC Health Services Research, 16(1), 431. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1695-9

Bolandianbafghi, S., Salimi, T., Rassouli, M., Faraji, R., & Sarebanhassanabadi, M. (2017). Correlation between medication errors with job satisfaction and fatigue of nurses. Electronic Physician, 9(8), 5142-5148. doi:10.19082/5142

Buabbas, A. J., Alsaleh, F. M., Al-Shawaf, H. M., Abdullah, A., & Almajran, A. (2018). The readiness of hospital pharmacists in Kuwait to practise evidence-based medicine: A cross-sectional study. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 18(1), 4. doi:10.1186/s12911-018-0585-y

Carayon, P., Wetterneck, T. B., Cartmill, R., Blosky, M. A., Brown, R., Wood, K. E., …Walker, J. (2014). Characterising the complexity of medication safety using a human factors approach: An observational study in two intensive care units. BMJ Quality & Safety, 23(1), 56-65.

Chalasani, S. H., Ramesh, M., & Gurumurthy, P. (2018). Pharmacist-initiated medication error-reporting and monitoring programme in a developing country scenario. Pharmacy, 6(4), 133. doi:10.3390/pharmacy6040133

Chiampas, T. D., Kim, H., & Badowski, M. (2015). Evaluation of the occurrence and type of antiretroviral and opportunistic infection medication errors within the inpatient setting. Pharmacy Practice, 13(1), 512.

Cho, I., Park, H., Choi, Y. J., Hwang, M. H., & Bates, D. W. (2014). Understanding the nature of medication errors in an ICU with a computerized physician order entry system. PloS One, 9(12), 1-13. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0114243

Cousins, D. (2018). Public-health burden of medication errors and how this might be addressed through the EU pharmacovigilance system. Web.

Elden, N. M., & Ismail, A. (2015). The importance of medication errors reporting in improving the quality of clinical care services. Global Journal of Health Science, 8(8), 54510. doi:10.5539/gjhs.v8n8p243

Ernawati, D. K., Lee, Y. P., & Hughes, J. D. (2014). Nature and frequency of medication errors in a geriatric ward: An Indonesian experience. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management, 10(1), 413-21. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S61687

Farzi, S., Irajpour, A., Saghaei, M., & Ravaghi, H. (2017). Causes of medication errors in intensive care units from the perspective of healthcare professionals. Journal of Research in Pharmacy Practice, 6(3), 158-165.

Freund, Y., Rousseau, A., Berard, L., Goulet, H., Ray, P., Simon, T., … Riou, B. (2015). Cross-checking to reduce adverse events resulting from medical errors in the emergency department: Study protocol of the CHARMED cluster randomized study. BMC Emergency Medicine, 15(1), 21. doi:10.1186/s12873-015-0046-1

Elmontsri, M., Almashrafi, A., Banarsee, R., & Majeed, A. (2017). Status of patient safety culture in Arab countries: A systematic review. British Medical Journal, 7(1), 1-15.

Ferracini, F. T., Marra, A. R., Schvartsman, C., Dos Santos, O. F., Victor, E., Filho, W. M., … Edmond, M. B. (2016). Using positive deviance to reduce medication errors in a tertiary care hospital. BMC Pharmacology & Toxicology, 17(1), 36. doi:10.1186/s40360-016-0082-9

Ghobashi, M. M., El-ragehy, H. A., Mosleh, H., & Al-Doseri, F. A. (2014). Assessment of patient safety culture in primary health care settings in Kuwait. Epidemiology Biostatistics and Public Health, 11(3), 1-11.

Gorgich, E. A., Barfroshan, S., Ghoreishi, G., & Yaghoobi, M. (2015). Investigating the causes of medication errors and strategies to prevention of them from nurses and nursing student viewpoint. Global Journal of Health Science, 8(8), 54448. doi:10.5539/gjhs.v8n8p220

Hernandez, F., Doursounian, L., Feron, J. M., Robert, C., Hejblum, G., Fernandez, C., Hindlet, P. (2015). An observational study of the impact of a computerized physician order entry system on the rate of medication errors in an orthopaedic surgery unit. PloS One, 10(7), 1-10.

Hs, A. S., & Rashid, A. (2017). The intention to disclose medical errors among doctors in a referral hospital in North Malaysia. BMC Medical Ethics, 18(1), 3. doi:10.1186/s12910-016-0161-x

Janmano, P., Chaichanawirote, U., & Kongkaew, C. (2018). Analysis of medication consultation networks and reporting medication errors: A mixed methods study. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 221. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3049-2

Jember, A., Hailu, M., Messele, A., Demeke, T., & Hassen, M. (2018). Proportion of medication error reporting and associated factors among nurses: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nursing, 17(9), 1-18. doi:10.1186/s12912-018-0280-4

Johnson, S. P., Adkinson, J. M., & Chung, K. C. (2014). Addressing medical errors in hand surgery. The Journal of Hand Surgery, 39(9), 1877-82.

Kalmbach, D. A., Arnedt, J. T., Song, P. X., Guille, C., & Sen, S. (2017). Sleep disturbance and short sleep as risk factors for depression and perceived medical errors in first-year residents. Sleep, 40(3), 1-10.

Kang, H. J., Park, H., Oh, J. M., & Lee, E. K. (2017). Perception of reporting medication errors including near-misses among Korean hospital pharmacists. Medicine, 96(39), 1-10.

Krzyzaniak, N., & Bajorek, B. (2016). Medication safety in neonatal care: A review of medication errors among neonates. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety, 7(3), 102-19.

Magal, P., Spiller, H. A., Casavant, M. J., Chounthirath, T., Hodges, N. L., & Smith, G.A. (2017). Non-health care facility medication errors associated with hormones and hormone antagonists in the United States. Journal of Medical Toxicology, 13(4), 293-302.

Mankaka, C. O., Waeber, G., & Gachoud, D. (2014). Female residents experiencing medical errors in general internal medicine: A qualitative study. BMC Medical Education, 14(1), 140. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-14-140

Mekonnen, A. B., Alhawassi, T. M., McLachlan, A. J., & Brien, J. E. (2017). Adverse drug events and medication errors in African hospitals: A systematic review. Drugs – Real World Outcomes, 5(1), 1-24.

Mohanty, M., Lawal, O. D., Skeer, M., Lanier, R., Erpelding, N., & Katz, N. (2018). Medication errors involving intravenous patient-controlled analgesia: Results from the 2005-2015 MEDMARX database. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety, 9(8), 389-404. doi:10.1177/2042098618773013

Mostafaei, D., Barati, A., Mosavi, H., Estebsari, F., Shahzaidi, S., Jamshidi, E., & Aghamiri, S. S. (2014). Medication errors of nurses and factors in refusal to report medication errors among nurses in a teaching medical centre of Iran in 2012. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 16(10), 1-10.

Nanji, K. C., Patel, A., Shaikh, S., Seger, D. L., & Bates, D. W. (2016). Evaluation of perioperative medication errors and adverse drug events. Anesthesiology, 124(1), 25-34.

NCCMERP. (2018). About medication errors. Web.

Nevalainen, M., Kuikka, L., & Pitkälä, K. (2014). Medical errors and uncertainty in primary healthcare: A comparative study of coping strategies among young and experienced GPs. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 32(2), 84-9.

Newbould, V., Le Meur, S., Goedecke, T., & Kurz, X. (2017). Medication errors: A characterisation of spontaneously reported cases in Eudravigilance. Drug Safety, 40(12), 1241-1248.

Nguyen, H. T., Nguyen, T. D., van den Heuvel, E. R., Haaijer-Ruskamp, F. M., & Taxis, K. (2015). Medication errors in Vietnamese hospitals: Prevalence, potential outcome and associated factors. PloS One, 10(9), 1-10. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138284

Nguyen, M. R., Mosel, C., & Grzeskowiak, L. E. (2017). Interventions to reduce medication errors in neonatal care: A systematic review. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety, 9(2), 123-155.

Nuckols, T. K., Smith-Spangler, C., Morton, S. C., Asch, S. M., Patel, V. M., Deichsel, E.L., … Shekelle, P. G. (2014). The effectiveness of computerized order entry at reducing preventable adverse drug events and medication errors in hospital settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Systematic Reviews, 3(1), 56. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-3-56

Patel, N., Desai, M., Shah, S., Patel, P., & Gandhi, A. (2016). A study of medication errors in a tertiary care hospital. Perspectives in Clinical Research, 7(4), 168-173.

Prakash, V., Koczmara, C., Savage, P., Trip, K., Stewart, J., Cafazzo, J. A., …Trbovich, P. (2014). Mitigating errors caused by interruptions during medication verification and administration: Interventions in a simulated ambulatory chemotherapy setting. BMJ Quality & Safety, 23(11), 884-92.

Radley, D. C., Wasserman, M. R., Olsho, L. E., Shoemaker, S. J., Spranca, M. D., & Bradshaw, B. (2014). Reduction in medication errors in hospitals due to the adoption of computerized provider order entry systems. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 20(3), 470-6.

Rishoej, R. M., Almarsdóttir, A. B., Thybo, H., Hallas, J., & Juel, L. (2018). Identifying and assessing potential harm of medication errors and potentially unsafe medication practices in pediatric hospital settings: A field study. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety, 9(9), 509-522. doi:10.1177/2042098618781521

Smith, K. J., Handler, S. M., Kapoor, W. N., Martich, G. D., Reddy, V. K., & Clark, S. (2015). Automated communication tools and computer-based medication reconciliation to decrease hospital discharge medication errors. American Journal of Medical Quality, 31(4), 315-22.

Tawfik, D. S., Satele, D. V., Sinsky, C. A., Dyrbye, L. N., Tutty, M. A., West, C. P., …Shanafelt, T. D. (2018). Physician burnout, well-being, and work unit safety grades in relationship to reported medical errors. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 93(11), 1571-1580.

Trockel, M., Bohman, B., Lesure, E., Hamidi, M. S., Welle, D., Roberts, L., & Shanafelt, T. (2017). A brief instrument to assess both burnout and professional fulfilment in physicians: Reliability and validity, including correlation with self-reported medical errors, in a sample of resident and practising physicians. Academic Psychiatry, 42(1), 11-24.

UBM. (2018). WHO launches program to reduce medication errors. Web.

Weant, K. A., Bailey, A. M., & Baker, S. N. (2014). Strategies for reducing medication errors in the emergency department. Open Access Emergency Medicine, 6(1), 45-55. doi:10.2147/OAEM.S64174

Westbrook, J. I., Li, L., Lehnbom, E. C., Baysari, M. T., Braithwaite, J., Burke, R., …Day, R. O. (2015). What are incident reports telling us? A comparative study at two Australian hospitals of medication errors identified at audit, detected by staff and reported to an incident system. Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care, 27(1), 1-9.

World Health Organization. (2016). Medication errors. Web.

Yousef, N., & Yousef, F. (2017). Using total quality management approach to improve patient safety by preventing medication error incidences. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 621. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2531-6

Zaghloul, A. A., Rahman, S. A., & Abou, N. Y. (2016). Obligation towards medical errors disclosure at a tertiary care hospital in Dubai, UAE. The International Journal of Risk & Safety in Medicine, 28(2), 93-9.

Zaree, T. Y., Nazari, J., Asghary, M., & Alinia, T. (2017). Impact of psychosocial factors on the occurrence of medication errors among Tehran public hospitals nurses by evaluating the balance between effort and reward. Safety and Health at Work, 9(4), 447-453.