Abstract

Palliative care is currently gaining more recognition and acceptability in medical fields as it is seen to be efficacious in reducing suffering of people in final stages of ailment and terminal stages of death. The objective of palliative care has always been to encourage, both the bodily and mental welfare of patient and family, which is done through specialty care forces. The significance of providing care to patients during the terminal stage has long been documented in Republic of Ireland, but literature reviews reveal that general practice registrars (GPRs) are not getting ample training in palliative care.

Methodology

Postal Questionnaires were sent to total number of 139 GPRs across whole of Republic of Ireland who had completed 1st and 2nd year of GPR (finishing GPVTS at the end of June 2008) and this was followed up twice with non-responding GPRs.

The main purpose of questionnaire were to estimate experience of GPRs with the degree of care afforded to terminally ill patients, the knowledge with palliative care training and assumed level of confidence and satisfaction with respect to the standards of care provided, including the knowledge levels of pain care and the management of palliative care patients. It also needs to look into the hopeful degree of confidence in applying knowledge of palliative care and also the competencies levels of GPR’s in the administration of pain relieving techniques and control management with respect to terminally ill cancer patients.

The scope of questionnaire allowed open ended questions that facilitated GPRs to write qualitative replies about the palliative care learning and the questionnaire was prepared specifically for this study. This questionnaire was next piloted for face validity and readability with groups of GPs and palliative care consultants.

Copies of these questionnaires were also sent to ten palliative care consultants for them to provide answer knowledge based palliative care questionnaires.

The GPRs knowledge premised replies were compared with the responses provided by consultants and the Data were spread sheeted in Excel and all responses to questionnaires were analyzed

Results: It is seen that most GPRs were much satisfied with their course coverage on the management of pain, other symptoms and communication skills and were also fairly confident in using the training gained in these areas. They also manifested good levels of knowledge in management of cancer-related pain; however, there was less satisfaction with exposure to use of syringe driver (38%) and trauma associated with losses, and nearly 36% believing that they have inadequate skills in dealing with bereavement scenarios.

Conclusions

It is seen from a survey of this kind that GPRs have varied views about their palliative care knowledge and management. It is expected that potential educational packages should ensure that GPRs are endowed with designed, structured and disciplined instructions in pain, tackling death issues and realistic acquaintance with exercise of hypodermic drivers. Both Irish college of General practitioner training body and palliative care providers should investigate ways of working more intimately together with providing GPRs with more expertise in palliative care management.

Introduction to Palliative care

The availability of hospices, palliative care professionals, and financial provisions for palliative care are inadequate to meet the increasing needs of aging population, even though palliative care is the new speciality in medical care for terminally ill and those at the end of life. Palliative care was primarily associated with terminal care of patients with cancer and hospice movement. But, over the years, hospice model has transformed with the emergence of newer healthcare challenges from chronic and terminal illnesses like HIV/AIDS, cancer, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases, etc.

Since there is a decrease in number of hospital beds due to over-institutionalization of health care, there is increased interest in promoting palliative care at home. Moreover, people in European countries prefer to die at home due to the continuing tradition of family care, and hence, there will be more demand for support of trained palliative care team for home care. Doyle et al 2004 states that “palliative care at home is dependent on the attitudes and perceptions of family physicians and wider socio-cultural attitude”, but the ignorance of the latest techniques and developments in palliative care may prevent it from percolating into health care delivery system.

In any primary health care system the general practitioners and nurses play an important role in palliative care at home, and their knowledge and experience are crucial in success of the initiative. It is found that palliative care has been unknown to many of GPs until recently and introducing this complementary service in home care and pain management is also not very well understood by many GPs in the Republic of Ireland. Thus, it has to be construed that the efforts to develop a system of palliative care training provisions in Republic of Ireland are still not very well organised, which warranted an assessment of the effectiveness of training in palliative care with specific emphasis on GPRs.

A study of undergraduate teaching in palliative care in Irish medical schools was conducted by Dowling and Broomfield in 2003 and it was found that: “identification of teachers proved to be difficult; most appeared to be unaware of what teaching other than their own was occurring within their medical schools in this discipline; and in no school teaching is centrally coordinated.” Literature reviews show that no study to assess the learning outcomes of general practice registrants in Republic of Ireland has been conducted so far. Hence, this study aims to assess palliative care knowledge among all general practice registrars, who are expected to complete their first year GPRs and final year GPRs of study by the end of June 2008 in Republic of Ireland through a quantitative questionnaire survey.

The wide range of options available to a General Practitioner and general health professional, may seem more attractive, or important in day-to-day practice, which causes shortage of trained workforce to attend to palliative care.

The importance of providing care to patients during the terminal stages of illness has long been recognized in Ireland and the first education and training course in hospice care was initiated in 1986, followed by palliative care course in 1990. A fillip to palliative care in Ireland was received with the governmental intervention for drawing up of the National Cancer Strategy, this introduced palliative care.

Сontent in the curricula of basic and post basic education of nurses, physicians, and other allied health professionals. It is also worth noting that Ireland was the second country in Europe to recognize palliative medicine as a distinct medical specialty in the year 1995. But, Irish Health Strategy identifies several weaknesses in health care system, among other things ‘fragmentation of services’, ‘inadequate linkages between services’, ‘underdeveloped community-based services’, ‘long waiting time for services’, and ‘systems for measuring effectiveness was either unavailable or under-utilized’(Department of Health and Children. Report of the National Advisory Committee on Palliative Care2001)

The Health Services Executive (HSE) of Ireland provides hundreds of different services in hospitals and communities across the country. These services include a broad spectrum of care in various places, ranging from severe to non –severe specialist palliative care (SPC), inpatient units, to residence and community based assistance and death losses support, which can be measure in several ways across the deliverance system.

Recognizing the potential of palliative care to alleviate pain and distress and need to work with all to make available adequate care, current SPC services include: “specialist palliative care inpatient units; home care; day services; specialist palliative care in acute general hospitals, community and other intermediate level of inpatient care in community hospitals; bereavement support; and education and research.” (The Irish Hospice Foundation, 2008). (Palliative care for all: Current specialist palliative care services include 2008).

It is experienced that specialist palliative care services have traditionally been directed towards people with malignant diseases, with a number still restricting their services almost exclusively to people with cancer. Services for people with life-limiting diseases, including chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, dementia, and heart failure have been either under-developed or fragmented in Ireland. Drawing experience from end-of-life strategies adopted as part of health policy in the UK, USA, and Canada, which have developed a number of disease-specific guidance documents, a fresh beginning has been initiated in Ireland through integrating palliative care into disease management framework.

What is palliative care?

The World Health Organization defines palliative care as the “active total care of patients whose disease is not responsive to curative treatment” (WHO, 1990). Palliative care can be described as an “approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychological and spiritual (The Irish Hospice Foundation, 2008).

Dame Cicely Saunders, who started hospice movement at St. Christopher’s Hospice in London in 1967, is considered as the pioneer in palliative care, and her maxim was “You matter because you are you, and you matter all the days of your life”, which emphasizes her vision of alleviating pain of terminally ill even in their death bed (Department of Health and children 2001). Witnessing the suffering of patients for hours at a time between doses of painkilling medication, she introduced the idea of pain relief on demand.

Saunders was keen on having a system that provided total care combining perspective that acknowledged all of the complications the dying have to face and assist them in meeting these challenges, but with lesser pain. “Dying patients need to be assured that their destiny lies in the hands of well trained, multi-disciplinary, professional team because often the dying are no longer capable of caring for themselves or from family.

There is strong focus in the UK on integrated care pathways and programmes such as the Gold Standards Framework for the dying patients who seek to ensure that such patients receive seamless, well co-ordinated and optimum care in the last few days and months of their life. In the U.K. the gold standards framework (GSF), a systematic evidence based approach, is concerned with “helping people to live well until the end of life and includes care in final year of life for people with any end stage illness” and its aim is to develop a locally-based system to improve and optimize the organization and quality care for patients and their carers in the last year of life (NHS,) (Thomas, 2005).

The GSF process is posited on improved communication to identify patients in need of palliative/supportive care towards the end of life, assess their needs, symptoms, preferences, and any issues important to them, and care planning based on the patient’s needs and preferences and enabling to fulfil them The key tasks under GSF practice comprise seven C’s, namely:

- communication;

- co-ordination;

- control of symptoms;

- continuity including out of hours;

- continued learning;

- carer support; and

- care in the dying phase.

Since the GSF primary care programme contains multiple tools, tasks, and resources it is more suitable for adoption within General practices and community nursing teams in Ireland.

Palliative care in Republic of Ireland

Although development of palliative care services is generally concentrated mostly in the west European countries, hospices and palliative care organizations are operating in Republic of Ireland for decades. The health system in Republic of Ireland is run by Health Service Executive (HSE) and palliative care is considered as the oldest of all medical specialities. The Republic of Ireland acknowledges to “have a duty of care to our patients and we also recognise the need to address the pain and suffering inevitably experienced by family members.

By achieving and maintaining an optimal level of pain and symptom control for our patients, we create space and opportunity where they are free to address the many personal issues that inevitably surfaces,” (Department of Health and Children, p 8). As such, the Irish authorities are perceived to have shown leadership and direction by becoming the second country in Europe to recognise palliative medicine as a distinct specialty in 1995.

This provided a unique opportunity that ensures every person in Ireland requiring palliative care getting access with ease to services of highly trained and coordinated professional team provided in a time and place determined by the specific needs and personal preference of the patient. Since the publication of the Report of the national Advisory Committee on Palliative Care (NACPC), in 2001, which provided the framework for the development of palliative care services for people with advanced and life threatening diseases in Ireland there has been considerable progress in palliative care services. There is a structured, three level specialisation in palliative care delivery in Ireland, namely:

- Level One approach in which palliative care principles are appropriately applied by all health care professionals

- Level Two of General Palliative Care which is an middle range stage where a chuck of patients and families will gain from the proficiency of health care professionals who may not always be busy full time in palliative care but had some supplementary guidance and understanding in palliative care, and

- Level Three Specialist Palliative Care in which the services’ core activity is limited to providing palliative care.

Under this system severely ill patient can opt to receive palliative care at home as it would allow him/her to spend quality time with his/her families. General Practitioners will make home visits and the specialist palliative care team also works with the General Practitioner. There is an ever increasing demand for palliative care services, but, due to lack of staff to main palliative care facilities, care service is adversely affected in Ireland.

It is expected that establishing an Institute for Hospice and Palliative Care in Ireland with the goal “to develop knowledge, to promote learning and to influence policy in all areas of supportive, palliative and of life care” would contribute to the evidence base for palliative care, would assist in the creation of a sustainable and skilled workforce, and would serve as a beacon of inspiration to other countries” (Clark, 2007).

Palliative care models

There are several models of palliative care, such as domiciliary, inpatient, outpatient, and consultative settings existing at present. In domiciliary setting, home care is delivered at the patient’s home through general practitioners, family physicians, and community nursing personnel. The team comprises either a palliative medicine specialist with clinical nurse specialist skill to deliver care or all-nurse team highly skilled in palliative care.

Inpatient settings include hospices for the terminally ill, general or specialized units in hospitals or nursing homes, and homes for the elderly and terminally ill children. Inpatient services work in association with interdisciplinary team, and specialists, such as oncologists, anaesthesiologists, pharmacologists, and interns can also constitute the team. The out patient/consultative settings cover hospices or specialized units in hospitals for day care for terminally ill patients, besides trans-mural and intra-mural support.

Day hospices in the Ireland are located under specialized palliative care units, which operate on weekdays to create a low key clinical environment, provide care for about 5 to 15 patients each day. Day hospice emphasizes on personal worth and provides respite to family and friends during the time patients are under the care of day hospice.

Recently, new models of domiciliary care have been developed in Ireland, known as rapid response teams and respite care teams. The rapid response team is engaged in emergency crisis intervention service when the terminally ill patient under home care is in crisis and the team consists of a medical palliative care specialist and a palliative clinical nurse specialist.

Background and Literature review

Search Strategy

The search strategy adopted web-based searches of informative site like PubMed, and also used Palliative care and General practice textbooks,

It was also deemed necessary to read publications of Department of Health and Children, (DoHC), Government of Ireland publications works and medical and scientific works undertaken by both public and private institutions and agencies that underpin the palliative care provided to terminally ill patients by General Practice Registrars under Irish settings.

Initial findings are suggestive of the fact that registers of palliative patients are being maintained under the supervision of GPRs, and often, cases of patients are discussed with health care specialists and carers during primary health care meetings.

It is also seen that enhanced use of symptom assessment models and techniques, along with the procedures to management of losses due to death, and also care of terminally ill patients are taken up. (Charlton 2008).

Again, in the article on palliative care research published in The Journal of Medical Ethics 2002, it is seen that the need to develop clinical and policy decisions that would guide palliative care would need to be set against the tenets “that value the practical and ethical challenges of palliative care research as unique and insurmountable. The review concludes that, provided investigators compassionately apply ethical principles to their work, there is no justification for not endeavouring to improve the quality of palliative care through research.” (Jubb, 2002).

‘Mortality data for Ireland shows that of the 27,479 people who died in 2006, 29% died from cancer, 14% from respiratory disease and 35% from disease of the circulatory system including health disease. Almost 16,000 of these deaths were in the 75 to 94 age group’ (Edmonds et al, 2001). This data establish the necessity of palliative care to handle the constantly increasing aging population with progressive and life-limiting illness, such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases and respiratory diseases that are to be encountered in coming years.

Palliative care aims to relieve pain and other symptoms of critically ill patients by providing care either to hasten or delay death and preparing the family for a smooth bereavement. It is viewed as a treatment intended for patients who are not expected to recover from their incurable illness completely. Although, “patients who receive palliative care are not expected to be cured, it is not unknown for patients to recover and be discharged off their illness” (O’Brien, 1995).

Hence, dying patients are entitled to receive treatment like all other patients for the rest of their life, and a “high standard should be allowed in all disciplines of palliative care that will benefit both parties” (Department of health 1996). By providing support in the form of pain medication, technical, social or psychological support for “enjoyable interactions of dying patients”, “they can live what is left of their lives as productively as possible” (More and Allen, 1990; Fowlie and Fordyce, 1989). The Republic of Ireland traces its palliative care history through

the contribution and influence of Mother Mary Aikenhead. Currently, a multidisciplinary palliative care team is composed of doctors, nurses, occupational therapist, a social worker and a physiotherapist. While there exists urban home care in Ireland dealing with palliative care, services are basically delivered by hospices such as Lady’s Hospices, or Harold Cross and other acknowledged and established home care services such as St. Francis Hospice in Raheny (Ling and O’Siorian, 2005).

The organization of palliative care is said to differ greatly (Abu-Saad, 2000). Wilkinson et al (1999) proposed that “there are few consistent trends in consumer opinion on and satisfaction with specialist models of palliative care,” But most GPs were also perceived to retain their role in palliative care (Shipman, 2002), and that most patients needing palliative care wish to maintain contact with their GP (Brenneis, 1998).

So far as palliative care education and research in Ireland is concerned studies point out that:

- There is no clear leadership to promote academic endeavours in the field of palliative and hospice care—Ireland has no full time profession in hospice of palliative care, there is no focus for research and published studies are limited in number and impact.

- Palliative care educational and research endeavours are highly localised, with little evidence of national planning or co-operation

- There is a tendency for local enthusiasts not to share plans and aspirations with other groups and organizations. (All Ireland institute for hospice and palliative care, 2007).

Though the Report of the National Advisory Committee on Palliative Care published in 2001 and subsequently adopted as official policy in the Republic of Ireland for the development of palliative care services reflects the increased attention at government level to hospice and palliative care, the evidence of deficit in education and research activities prompted this study to evaluate the training needs of GPs in Ireland..

Palliative care service evaluation

Palliative care is being adopted in more and more areas of health care. However, there is little research data available to evaluate palliative care services, because of the difficulties in getting realistic responses on the effects of palliative care from those who are at the end of life, and what is in circulation are poorly conducted studies (Seale, 1989; Mor and Materon, 1987). Available studies on the subject reported less pain, less fear of death, and better quality of life for patients getting palliative care (Parkes, 1985: Hendon and Epting, 1989; Wallston et al, 1988).

The largest multi-centre experimental study by Greer et al (1986) has shown few differences in patient’s quality of life with palliative and other care of the terminally ill. In Ireland, most people with life-limiting diseases other than cancer are cared for largely by the General Practitioner at present, and it is known that the existing level of care for such people is under-developed, and in some cases it is based on episodic treatment primarily in the acute hospital settings.

There are also variations in capacity issues relating to hospital-based consultants, clinical nurse specialists, and the multidisciplinary team leading to inequality in services across areas and the country. A study by Addington Hall et al (1998) projected that there would be an increase of at least 79% in case load for specialist palliative care specialist if their services are made fully available to patients with a disease other than cancer. In 2005, a study by Rosenwax identified that between 0.28% and 0.5% people in the general population in any year could potentially benefit from a palliative care approach. [Addington-Hall, et al. (1998); Rosenwax, L.K., et al. (2005).].

A survey of patients with non-malignant diagnosis who were referred to specialist inpatient unit in Ireland over a six year period from 2000 to 2006 conducted by Corcoran found that 6.35% of all referral to community specialist palliative care (SPC) services, and 2.9% of all referrals to SPC inpatient unit were non-malignant (Corcoran, M,2006). It implies that specialist inpatient units can contribute a wide range of services to care of patients with diseases other than cancer through direct patient care and indirectly through palliative education for both specialist and general staff.

- Older age and frailty may be surrogates for life-threatening illness and co morbidity, but there is no exact definition of ‘end of life.’ (All Ireland institute for hospice and palliative care, 2007).

One of the key aims of specialist palliative care should be to disseminate education leading to empowerment of generic healthcare workers, based on the Liverpool integrated care pathway for the dying patient developed the Royal Liverpool University Hospitals Trust and Marie Curie Centre Liverpool, for adopting best practice for the care of dying patients. (Ellershaw & Ward, 2003, p.30-34).

The National institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines on supportive and palliative care for adults with cancer recommend that a “four level model of psychological assessment and intervention” be developed and implemented in each cancer network. Enquiry with all 224 hospices in the UK and Republic of Ireland with inpatient beds to know the level of psychological support available to them, according to NICE guidelines, has shown that hospices have less access to professionals trained in the management of psychological and psychiatric problems than recommended by the NICE guidelines. (Price et al, 2006, p.637-639).

Palliative care teaching in Ireland

“In relation to education and training programmes, general training and programmes for continuous professional development are needed for all members of the multidisciplinary team involved in the delivery of supportive, palliative and end of life care”. It is opined that among the three levels of palliative care education the “integration of core competencies and curricula for level 1 and Level 2 remains to be achieved for all health professionals”

All-Ireland Institute for Hospice and Palliative care. (2007) (All Ireland institute for hospice and palliative care, 2007). There has been an increase in the teaching of palliative care over the past 3 decades, but studies indicate that the emphasis given by medical schools to this important subject is minimal. A review of medical school prospectuses in the United Kingdom and Ireland for 1997, showed that only 2 out of the 26 UK medical schools, and only 1 of the 5 medical schools in Ireland, referred to undergraduate teaching in palliative care.

The situation is not unique to Ireland alone, as available literature on palliative care training reveals that there is deficit in training world over. It is estimated that from 2001-2003, the number of hospital based palliative care programs has grown by over 60% and the position is such that, now one in four U.S hospitals has a palliative care program and Morrison et al (2005) suggests that all U.S medical schools must provide training in palliative medicine.

While it is generally understood that the junior hospital doctors are responsible for the care of dying patients, as hospital wards are the most common place of death, they are reported to have found palliative care very distressing and felt insufficiently prepared for the task (Firth, 1987). A survey of 80 GPs found that those who had undergone vocational training prior to compulsory requirement, received better palliative care training than those who did not attend the vocational schemes (Doyle et al, 1982).

In another study (Charlton et al, 1999) of 210 GP registrars in the West Midlands, UK, that evaluated self perceived skills in palliative care, perceived skill ratings were seen to increase throughout the GP registrar year in the absence of a specific course. In this process, the anxiety about caring for the dying patient was observed to increase. This confirms Doyle’s (1982) proposal that vocational training in general practice has a positive impact on palliative care knowledge and skills.

Studies on the palliative care educational needs of GPRs by MacLeod in 1991 found that 90% of respondents wished for teaching on control of other symptoms, whereas 97% respondents thought teaching on personal coping mechanisms to be vital. In addition, most felt comfortable in pain control, but nearly half of the GPs found difficulty in treating loss of appetite, lack of bowel control, and unpleasant smell associated with incontinence (Grande et al, 1997).

In another study in Canada, where continuing medical education is required to maintain accreditation, it was found that family physicians feel inadequately trained in pain and symptom management aspects of palliative care (Oneschuk and Bruera, 1998). One study concluded that teaching tends to be fragmented, ad hoc, and lacking in coordination and it tends to focus on acquisition of knowledge and skills rather than attitudes. It added that all doctors were willing to encounter patients with palliative care needs, but the timing of teaching about palliative care has not been adequately researched.

The study suggested that each medical school should institute guiding principles to expand an incorporated programme for palliative care, with due reference to the multidisciplinary nature of palliative care. Majority of the studies suggest that a formal educational program be developed to establish a firm knowledge base in palliative care early in the medical educational process and this knowledge be reinforced throughout the medical school and postgraduate training and in clinical practice

GP involvement in palliative care

GPs are usually the patient’s point of first contact to the medical system that provides primary medical care to all patients, and they also act as gatekeepers to the health system. Nevertheless, palliative care properly delivered involves practitioners from many disciplines, and most of the time, GPs fill a crucial coordinating role. It is also expected that when the GP and primary care work well, it follows that the medical system as a whole works more efficiently (Starfield. 1980).

Knowledge of the GP about his or her patient and the family environment developed over many years of care consequently adds value to the content knowledge of experts in palliative care nursing and medicine. In addition, it was also suggested that there are benefits gained from specialists and GPs working closely together but its veracity is not easy to confirm. Result of collaboration amongst GPs and specialist teams improves the condition of patients, improved diagnostic accuracy results from the GP participation in palliative care teams, application of evidence-based treatments, identification of systematic problems in the delivery of care, and improved ability to facilitate deaths at home (Grande et al, 1997; Mitchell, 1998, Robinson, 1994, and Costantini, 1993 ).

It was also found that patients of GPs working alone fared the worst while teams involving a nurse specialist, GP, and a district nurse provided the best services for patients who required symptom relief, and in most cases, lack of communication was causing dissatisfaction to relatives of patients (Hearn and Higginson, 1998 and Blyth,1990).

In a recent survey of family members of patients who died in hospital, it was suggested that the factors contributing to poor care included a lack of open communication, difficulties in prognostication and a lack of advanced care planning (Cherlin, 2005). In addition, palliative care services have improved patient satisfaction, as well as and resulted in decreased ICU days, and decreased hospital costs (Gomez-Batiste, 2006). This has led to standardization of processes developed to assist physicians and nurses caring for terminally ill patients in hospitals (Ellershaw, 2007).

GPs’ self-assessment of pain and symptom control

On the self-assessment of pain and symptom control part of the general practice registrars, Haines and Boroff (1986) reported that 32% of GPs frequently or always had trouble in controlling pain, while 45% had trouble with the emotional distress of patients or relatives. However, the proportion of GPs who report difficulty in managing pain has recently improved. GPs’ and district nurses’ self-assessment about the palliative care they delivered described fewer negative outcomes.

Consequently, poor pain control was reported amongst 15.7% of the respondents, and poor control of other symptoms ranged from 13.8% (nausea and vomiting) to 21% (depression and dyspnoea). Seamark (1996) also found that only 8 of 79 GPs frequently or always had difficulty in controlling pain, while 25 of 79 (32%) had problems managing other symptoms; 18 of 79 (23%) in managing the emotional distress of carers; and 5 of 79 (6%) with their own responses to a patient’s death (Semark et al, 1998).

There was also reported discrepancy between pain and symptom control between GPs and carers highlighting the role perception has in the observation of patient symptoms. The observations of health professionals have been shown to correlate with self-reported distress as compared to those observed by carers (Butters et al, 1993 and Tierney et al, 1998). Likewise, there is difficulty in determining the actual amount of distress, as many studies rely on retrospective reporting about the course of the illness.

Symptom identification and GP clinical methods

According to Jones (1994), GP identification of the most common symptoms suffered by patients did not correlate with the symptoms patients actually suffered. Maguire also found that in terminally ill colorectal cancer patients, there exists only moderate correlation between patient symptoms and GP perception of the presence of symptoms. Likewise, there was even poorer correlation between carers and patients (Maguire et al, 1999). Grande et al also indicated that GPs frequently failed to identify those symptoms they found difficult to manage, and those seen less commonly.

GP knowledge and clinical practice of opioids

GP knowledge of symptom-control strategies was perceived to be in favour of patients. Shipman and colleagues showed that GP knowledge of the key issues of pain and symptom control amongst East Anglia GPs was sound (Shipman et al, 2001). In addition, GPs appeared to treat palliative care symptoms properly. Rees (1987) indicated that the majority of British GPs used the appropriate forms of opioid available at the time, and patients receiving regular opioids increased significantly between 1981 and 1985. In another study, 64% of patients were given opioids by their GPs and were commenced on laxatives at the same time (Lang et al, 1992).

The study showed that 70% of patients referred by GPs to hospice-prescribed opioids were also prescribed laxatives. While providing pain relieving sedation in the administration of pain relieving injections, the four tenets are that there should be no traces of malice or lack of morality in the act, the intentions of the health carer must be good, death must not be seen to be the end and good effects must outweigh the bad ones. It is well established that in terminal situations the intent of the patient, like that of the health care provider, must also be considered, and in the use of Palliative care service the intent must be to relieve suffering, not to hasten or cause death

Pain and symptom control by GPs

While there had been reported improved patient outcomes from GP participation in palliative care teams, the performance of GPs in delivering optimal pain and symptom control remains doubtful. Likewise, it was also suggested that the performance of GPs in controlling pain and other symptoms is worse than practitioners caring for patients in in-patient units. (Addington, 1995). Relatives of people who participated in a 1990 national survey in the UK whose family members died of cancer said that at some stage in the last year of life, 88% were reported to have been in pain, and 66% were said to have found it to be very distressing’.

GPs apparently gave treatment that only partially controlled the pain, or not at all. Seale and Cartwright (1994) also noted that 67% of dying patients without cancer complained of pain in the last year of life. In Germany, Busse et al (1998) reported a whopping 100% of 47 terminally ill patients under home care complained of pain in the last few days of life, but 57% of cases claimed satisfactory control (Busse et al, 1998). Other common symptoms like loss of appetite, constipation, dry mouth or thirst, vomiting or nausea, breathlessness, low mood, and sleeplessness were reported by more than half the respondents in respect of patients in their last year of life.

Palliative care training for doctors

Some studies suggest that training for doctors in palliative care was not extensive. There was a lack of training available in undergraduate medical schools, and almost none reported by GPs in their hospital training. Barclay et al (1997) indicate that more than 70% GPs claimed to have no training in communication skills or bereavement care. However, more training was available during vocational training for general practice, but this was also perceived to be inadequate.

Lloyd-Williams (1996) found that only 15% of recently graduated UK trainees received tutorials on palliative care from within their practice while less than a third felt that they had received adequate teaching on pain and symptom control, and fewer than 10% perceived the teaching on psychological support to be adequate. Shipman et al reported that half of a sample of British GPs wished to have education in symptom control for non-cancer patients while inner city GPs wanted more education in opiate prescribing and the control of nausea and vomiting (2001). Training as junior doctors was also particularly rare, but during the GP trainee year it was much more common.

Confidence in palliative care is reported to improve during the GP registrar year in the UK. For some experienced GPs, most areas had been covered but more than 20% claimed no training in communication skills and bereavement care. Studies also suggest that “for some GPs, exposure to only a small number of palliative care patients each year, combined with rapid advances in the evidence base for palliative care, undermines their confidence in managing patients appropriately” (Mitchell, Reymond and McGrath, 2004).

By laying down a baseline set of pain relieving care to be inculcated among all doctors at the undergraduate and intern level and interfacing with pain control patients would make sure that all general practitioners have the knowledge and confidence to manage most common problems in pain relieving care. It is well recognized that standard of care for the dying patients is dependent on the training and knowledge of palliative care provider(s), and every GP should possess adequate knowledge in all aspects of such care. A high standard represents accuracy of training and the appraisal of knowledge according to the medical needs of the patient at a certain point of time.

A report from the Irish Department of Health and Children declares that “every person in Ireland who requires palliative care, will be able to access with ease a level of service and expertise that is appropriate to their individual need” (DoHC p.8). It appears that the service is expected to deliver highly trained and coordinated inter-professional team, which will depend on the specific needs and preference of the patient at a certain time and place.

Data protection and ethics

All the response forms completed by the General Practice Registrars need to be dealt with absolute secrecy and confidentiality. This could be used only by authorised personnel for the purpose of this research only and not for any other purpose, and no unauthorised person could have access to these documents. Thus, it is necessary to these to be kept in a separate locker with access to the official investigator only.

With regard to the electronic data it is seen that all materials necessary and relevant for the purpose of this study be stored in computers in separate folders, totally password protected and with access only to the official investigator.

It is mandatory that contents of these folders be deleted after a period of six months from its entry in the electronic data base.

In a research of this kind which is based on questionnaires and anonymous respondents it is felt that the question of ethical considerations do not arise and thus no formal ethical approval has been sought.

Importance of pain care and syringe drivers in palliative care

Importance of pain care

Nurse Saunders identified ‘total pain’ as a fundamental issue in treatment and introduced the idea of pain relief on demand and helping patients ‘to live until they die’, because pain relief had been dealt with as a purely medical issue during 1960s. She envisioned total care through an integrated approach that recognized all the difficulties faced by those at their end of life.

“The aim of palliative care is to allow patients to be pain free or, for their pain to be sufficiently controlled so that it does not interfere with their ability to function or detract from their quality of life”.( palliative Care Victoria ) Good pain control could be achieved only through accurate and detailed assessment, and reassessment, of each pain; knowledge of the different types of pains; change in approach to chronic pain, and knowledge of treatment modalities as well as actions, adverse effects, and pharmacology of analgesics. In palliative care the analgesic program should be kept simple, even for patients in severe pain, and oral medication should be resorted to the maximum possible situation.

Symptom management is paramount in palliative care, which requires skilled comprehensive assessment and attention to the whole person, and strategies should be designed around the patient’s psychological, spiritual, cultural, and social needs. The first principle of managing cancer pain is an adequate and full assessment of the cause of the pain, remembering that most patients have more than one pain and different pains have different causes.

A comprehensive knowledge of the underlying pathophysiology of pain is essential for effective management of suffering. Affliction has four parts, bodily, mental, community and godly and there has been a large degree of progress to make comfort-focused care routinely and readily available in hospitals and health systems through palliative care. Pain and dyspneoa, either separately or in combination, is known to contribute the most to symptom burden in seriously ill hospitalized patients. Analgesic drugs form the basis for pain control and the choice of drug should be based on the severity of pain.

The easiest way to contain pain is to provide opioids orally, and supplementing it with intermittent doses of short-acting opioids. If oral administration of the drug is still possible the dose of methadone may be increased in the event of increased pain. In case it is difficult to administer opioids orally, it can be given intramuscularly or subcutaneously. Drugs should be administered in standard doses at regular intervals and when non-opioid or weak opioid fails to give the expected effect a strong opioid should be used.

WHO’s three- step ladder to use of analgesic drugs should be the basis for selecting all pain relievers, and care must be taken with dose of each drug in the formulation. Morphine is the most commonly used strong opioid analgesic and the dose must be tailored to each patient and doses repeated at regular intervals, so that pain is prevented from returning. Opioid alternative to morphine are Hydromorphone, Fentanyl, Diamorphine, and Buprenophine, Dextromoramide.

Clinical experiences suggest that the simplest method is to prescribe a regular , four hourly dose of a quick release formulation of morphine and allowing extra doses of the same size for ‘breakthrough pain’ as often as necessary will be the best option. The process of assessing daily requirements and adjusting regular doses should be continued until pain relief is satisfactory. Once pain is relieved, a controlled release morphine preparation should be adopted to maintain pain relief.

Application of Syringe drivers

In palliative care subcutaneous drug infusion by portable syringe drive allows the continuous administration of medication to provide comfort to patients, when patients are unable to take medicines by mouth because of persistent nausea, vomiting, dysphagia, or weakness and co-ordination or cognitive function is impaired. Though a syringe driver takes 3 to 4 hours to establish a steady drug level in plasma, while resorting to syringe drive and mixing drugs it is essential to follow accepted palliative care guidelines, and drugs that are known to be effective via the subcutaneous route only should be used.

Diazepam, chlorpromazine, and prochlorperazine are found to be much irritant, when given subcutaneously. Hence, drug compatibility should be checked before mixing, in consultation with palliative care team, and the total dose of drug required in 24 hours calculated in advance and. If there is site irritation alternative routes may be considered.

For many patients subcutaneous infusion of opioid via an infusion device such as a portable, pocket sized, syringe driver is found to be more convenient. It allows continuous infusion of opioid analgesics if they are unable to take drug by mouth. The relative potency of opioid is increased when they are given parenterally: The oral dose of morphine should be divided by two to get the equal analgesic dose of subcutaneous morphine.

Though indication for administration of strong opioid by intrathecal or epidural routes remains somewhat controversial, there is agreement that patients with pain that is sensitive to opioids, experiencing intolerable adverse effects may be able to tolerate epidural or intrathecal administration. While prescribing opioids, it is essential to monitor its adverse effects as well. Common adverse effects of opioids are sedation, nausea and vomiting, constipation development, and dry mouth.

Opiod toxicity may be present as subtle agitation, seeing shadows at the periphery of the visual field, vivid dreams, visual and auditory hallucination, confusion and myoclonic jerks. These presentations should be managed by reducing the dose of opioid, ensuring adequate hydration, and treating the agitation with haloperidol.

Palliative care training in Ireland

Palliative care means “continuing total care for a patient and his/her family when there is no longer a medical expectation of cure” and it aims to provide the best quality of life and keep the patient free from pain as far as possible (Citizens Information, 2008). “We live in a world that is experiencing population ageing and in which expectations of a long life must also be matched with recognition that care at life’s end is a matter that faces every individual and the whole society” (Clark, David. 2007).

As with other European countries, Ireland’s population is ageing, and the demand on palliative care resources are expected to increase markedly in the next two decades. Coupled with this, changes in the demographics and work patterns of the general practice workforce will lead to difficulties in achieving the goal of home care for most people with a terminal illness, unless structural initiatives are put in place (Yuen et al. 2003).

Present national palliative care services in Ireland are developed according to the recommendations contained in the report of the National Advisory Committee on Palliative Care, published in 2001, and services are provided in many hospices, specialist units in hospitals, and in the home of critically ill. There are five specialist palliative care in-patient units in Ireland located in: Marymount Hospice in cork, Milford Care Centre in Limerick, Our Lady’s Hospice, Harold’s Cross, Dublin; St. Francis Hospice, Rahney, Dublin; and Galway Hospice.

Primary importance in palliative care is given for hospice service that generally involves home service. A home service usually involves home care, in which a nurse provides service to terminally ill people and their families and ‘twilight nursing’ organised by Irish Cancer Society is basically home care nursing service.

Though there is increasing demand for palliative care for the aged, chronically and terminally ill, it is pointed out that most western European countries continue to lack an academic infrastructure to support hospice and palliative care development, and Ireland is no exception. Even after having a rich tradition of hospice and palliative care in Ireland it is felt that “palliative care educational and research endeavors are highly localized, with little evidence of national planning or co-operation” (Clark, D, 2007)

Currently, Ireland has 6 medical schools, with an undergraduate palliative care curriculum. The General practice Vocational training or post graduate training starts after the Internship. The GP vocation training in Ireland stretches over a period of 3 years, which includes 2 years of hospital training and one year as a GP Registrar. However, recently this has been changed to 4 years GP vocational training consisting of 2 years hospital training and 2 further years General Practice training.

Although attempts were made to introduce palliative care training from undergraduate through to postgraduate education, it is not clear at what stage this training is best implemented to provide the most effective care in clinical practice. The Irish College of General Practitioners (ICGP), established in 1984, is the professional body for general practice in Ireland, and its primary aim is “to serve the patient and general practitioner for encouraging and maintaining the highest standard of general medical practice” (ICGP.(2007). Route to Training in General Practice) (Professional training and education, 2005).

The objective of specialist training in general practice is to produce doctors capable of providing personal and continuing care to individuals and families in the community, who have management skills relative to primary care and are able to audit their work with a view to improving performance. Peer review groups (PRGs) and quality circles (QCs) functioning in Ireland under the aegis of Irish College of General Practitioners is an important method of quality improvement in primary care. “Peer review has been widely accepted as suitable for quality improvement, because it encourages professional autonomy and supports critical insight and appraisal of quality of care.” (Beyer et al, 2003, p.443-451).

The official undergraduate curriculum for Irish medical schools was published in 1993 and a study of five medical schools in 2003 revealed that “no school has specific time dedicated to the teaching of palliative care”, though all medical schools appeared to fulfil the suggested curriculum. (Dowling and Broomfield, 2003). Similar example is reported in respect of the United Kingdom, where the modern hospice movement was founded in 1967 and expanded into speciality service in 1985.

A pre-course survey in 2003 revealed that 100% of respondents, 54% out of 250, felt that “they needed further training, and 51.5% said that they had no previous training in palliative care. (Charlton, Rodger and Currie, Andy. 2008).

A survey conducted by Oneschuk and colleagues in Canada in 2001 found that the median teaching time was only 10 hours. The survey result reveals that education and training in palliative care is not getting enough attention not only in Republic of Ireland, but in other parts of the world also. These studies suggest that medical students are not exposed to and have insufficient knowledge to confidently care for a dying patient, breaking bad news, or in coping with issues involving relatives’ grief. This important information about undergraduate and general practice training prompted to proceed assessing the current training experience of GPRs in Republic of Ireland.

Please write the summary of the literature review as requested by the examiner.

Summary of Literature review

The search strategy has taken recourse to web-based searches of informative site like PubMed, and also used soothing care and general practice textbooks.

Reference was made to publications of Department of Health and Children, (DoHC), government of Ireland publications works and medical and scientific works undertaken by both public and private institutions and agencies that underpin the palliative care provided to terminally ill patients by General Practice Registrars under Irish settings.

Palliative care is being used in more and more areas of health care. However, there is little research data available to assess palliative care services, because.

Of the difficulties in getting realistic responses on the effects of palliative care from those who are at the end of life, and what is available are ill conducted studies.

On the self-assessment of pain and symptom control part of the general practice registrars, Haines and Boroff (1986) reported that 32% of GPs frequently or always had trouble in controlling pain, while 45% had trouble with the emotional distress of patients or relatives.

Thus, it could be seen that Palliative care means “continuing total care for a patient and his/her family when there is no longer a medical expectation of cure” and it aims to provide the best quality of life and keep the patient free from pain as far as possible (Citizens Information, 2008).

Preliminary approach to the assessment

Aim of the study

The Republic of Ireland has a long history of recognising the benefits of palliative care to patients and their families, during the terminal stages of an illness, and of promoting both their physical and psychological well-being. Palliative care demands a great deal of support from the community, hospital, medical, and nursing services.

Mobilising the right resources and capability of healthcare providers are paramount for successful results. Since success of the program is dependent on the knowledge and skill of the health professionals involved in it, adequate training and knowledge of General Practitioner (GP), nurses, and other care providers of palliative care is essential. Because research reports show that there is lack of training in palliative care among GP registrars of Republic of Ireland, it is proposed to assess the knowledge in palliative care and outcome of trainings among General Practice Registrars in Republic of Ireland.

Research approach

“Educational research is research conducted to investigate behavioural patterns in pupils, students, teachers and other participants in schools and other educational institutions.” (Educational research: Resources,). There are two models of research, qualitative and quantitative, of which quantitative research is the systematic scientific investigation of quantitative properties and phenomena and their relationships.

The current study is a quantitative research that shall measure the actual experience and learning months of general practitioner registrars on palliative care in Ireland. Quantitative research is widely used in both the natural and social sciences with the objective to develop and employ mathematical models, theories, and hypotheses pertaining to natural phenomena. In this instance, it covers the actual total number of months or hours the General Practice Registrars had experience and learning on Palliative Care in Ireland.

It is one of the most widely used techniques of data gathering in the social sciences that makes available proficient compilation of data over large population, agreeable to self-administration, individual administration, by telephone, via mail, or over the global computer network. The process of measurement is central to quantitative research to provide the fundamental connection between empirical observation on the lack or sufficiency of time given or spent on palliative care among participants and to link this mathematical expression with quantitative relationships.

While the use of an experimental or quasi-experimental research design is critical for the purpose of predicting and establishing casual relationships the quantitative research approach in this study shall be guided by:

- Generation of models, theories and hypotheses

- Development of instruments and methods for measurement

- Experimental control and manipulation of variables

- Collection of empirical data

- Modelling and analysis of data

- Evaluation of results.

Sampling

Purposive sampling, a form of non-probability sampling, is proposed to be used in this study. In purposive sampling the researcher samples with a pre-determined purpose in mind from one or more specific and predefined groups, believed to be representative of the larger population of interest. Major benefit of purposive sampling is that it can be very useful for situations in which the researcher wants to reach a targeted group that otherwise might not be readily available. The population of interest for the study was general practice registrars in Republic of Ireland and the process comprises:

-

- Definition and limitation of the population of concern.

In this study, only vocational training General Practice Registrars (GPRs) is included and all of them are from Republic of Ireland. 139 were targeted but only 71 finally made it for inclusion in this research.

- Sampling frame.

- The questionnaire is framed to measure the Palliative care knowledge among general practice registrars in Republic of Ireland.

- Specify a sampling method for selecting items or events from the frame.

- The respondents are basically asked about specific interpretation and understanding on palliative care learning, experience, pain control and symptoms control, training, among others.

- Determining the sample size.

- This was done after all willing respondents submitted or returned the questionnaire with their proper answers.

- Implement the sampling plan.

- Four HSE regions were covered that include sub-groups from Dublin Mid Linster, Northeast, Southern and Northwest.

- Sampling and data collection.

- All General Practice Registrars from the First Year vocational training GPR’s and Second Year vocational training GPR’s groups were given questionnaire except those in vacations or on leave.

- Review the sampling process.

- A sub-group that will also determine any area of differences on palliative care experience, symptom or pain control and syringe drive will be points of comparison. Further, the respondents’ gender will also be noted.

Framing of questionnaire

A well-designed questionnaire is critical for achieving the purpose of survey research, and it concerns with validity, reliability, and must always be at the forefront of selection/construction process. By utilizing a questionnaire it is hoped that an understanding of the effectiveness of the palliative care training among the GPRs can be developed. It is envisaged that a model questionnaire, for which validity and reliability has already been established, will be located and finalized after a pilot study.

How study instrument was evolved

The study instrument was evolved through five page questionnaire containing multiple closed-ended questions to be replied by the respondents. It contained 27 questions with multiple choices and the instrument was send at random to 6 GPS for their responses.

Literature reviews show that no study to assess the learning outcomes of general practice registrars in Republic of Ireland has been conducted so far. Hence, this study aims to assess palliative care knowledge among all general practice registrars, who are expected to complete their first year GPRs and final year GPRs of study by the end of June 2008 in Republic of Ireland through a quantitative questionnaire survey.

Based on the methods adopted in earlier studies of similar nature in Ireland, U.K., and Australia a five page questionnaire containing 27 questions with multiple options, such as ‘Yes/No’, ‘Fair/Good/Very good/Poor’, etc., was prepared. For pilot study the questionnaire was sent randomly to six general practitioners for getting their comments and opinion on the questionnaire format and content.

The questionnaire was sent to palliative care consultant and a palliative care registrar also for gathering their expert comments on the questionnaire and suggestions for additions and alterations, On receiving the comments, opinions, and suggestions from the GPs and palliative care consultant and Registrar the questionnaire was finalised in consultation with my supervisor, Prof. G, Bury, which is given at Appendix A.

Data Collection

Next step was contacting the GPRs currently undergoing palliative care training in Ireland. Getting the list of GP Registrars was a little difficult as some of the GP training centres were not willing to provide the list either due to local protocol preventing it or unwillingness on the part of the centre. However, letters were sent to all 12 GP vocational training schemes centre directors as well as GP VTS administrator/secretary requesting them to circulate the questionnaire among GP registrants on their scheme.

The questionnaire was posted through land mail to these centres general practice registrars. Among the 12 GP vocational training schemes 11 centres have GP Registrars and their responses have been analysed. One GP vocational training scheme is without GP Registrars, and hence it has been excluded from the study. An Information sheet to the GP registrars, letter detailing purpose of the study, maintaining participant’s confidentiality, and using the data for assessment was also enclosed, along with questionnaire with self stamped envelope. The study is an anonymous one. (Given at Appendix B).

Follow-up of respondents

First reminder was sent to the GPRs after 3 weeks of sending the questionnaire, followed by reminders after a lapse of 2 weeks and one week respectively. Accepting questionnaire was closed after 8 weeks from the date of posting the questionnaire to the GPRs. Questionnaire was sent to 139 out of 149 GPRs in Ireland, available at the commencement of the study, and completed response sheet received from 71 GPRs within the stipulated time. The information received from the GPRs from four regions of Ireland has been fed into a data base and it is given at Appendix C. (Excel Sheet)

Identifying category of GP Registrars in Republic of Ireland

General Practice Training in Ireland is detailed below to facilitate readers in understanding the difference between first year and final year GP registrants.

- General practice training in Republic of Ireland consists of 3 years vocational training as well as 4 years vocational training. Vocational training is in postgraduate level specialist hospital and general practice location training, which start majority after completion of 5 years of under graduate medical school training, and one year of Internship.

- 3 year General Practice Vocational training consists 2 years of hospital training, 4 or 6 months of different specialty training, and one year as General Practice Registrars. GPR training is held in General practice training place, under a GP Trainer and seeing general practice patient in the community setting.

- In the questionnaire, final year GP registrars mean, they are in final year of 3 years GP training scheme or they are first year GP registrars and completing full training at the end of one year GP Registrars.

- In 4 years GP vocational training final years means second year as GP Registrars, who has finished 2 years of hospital training and are completing two years of General practice training in GP practice, who will be completing full training at the end of June 2008.

- The first year GP training means, they are undergoing 4 years GP Vocational training, and finished 2 years of hospital training and completing one year of GP Practice training at the end of June 2008.

Evaluation

The same GPR’s questionnaires were randomly sent to ten palliative care consultants in Republic if Ireland to give their answer to the knowledge based questions Q12 to Q18. It was decided in the beginning to evaluate these questions from the answers obtained from the ten palliative medicine consultants. Since there was uncertainty among the consultants to these questions, later it was decided to take majority of the consultant’s answers as a gold standard and also corrected against the world health organisation guidelines , the Oxford text book of palliative care and palliative care formulary 3.

Scope and limitations of the study

It was proposed to cover all the GPRs in four regions of the Republic of Ireland, for getting a clear picture of exposure to palliative care training in their curriculum. Whereas, the response rate was moderate (having 51% response to the questionnaire) with 49% non-respondents in this study reflects half-hearted attention to the survey. It may be probable that many GP registrants do not consider palliative care study as an important branch to assist their future career. Other likely reasons for moderate response may be due to the fact that it is a retrospective study, recall bias, or it did not include clinical data in the questionnaires to answer them.

Data protection and ethics I am not sure where you will put this paragraph (Included in P. 26).

All the responses form genera practice registrars , and analyzed material and all relevant material to this study was kept in a safe separate locker and only the investigator has the key to access

Electronic data – all the materials relevant to this study was stored in a computer with separate folder with password protected and only the investigator has the access to the folder.

Destroying the data: after six month of the completion the all the material will be destroyed in a safe manner.

Ethical approval was considered, since it is anonymous and questionnaire based study hence the thesis guide has decided to proceed without formal ethical approval.

Data analysis and results

Descriptive statistics has been used to describe and summarize the data obtained with the study.

Q. 1 to 4: General questions

Questions at serial number 1 to 4 have been framed to get demographic profile of participants. These questions covered the years of graduation from medical school, gender, age, and the HSE region they represent.

Q. 1: Year of medical graduation

There are 46 (65%) respondents enrolled for GPR training within five years of their graduation from clinical medical school. Of this, 20 (28%) are in first year and 26 (37%) are in final year. One each from first and final year registrars joined GPR training after 11 years from their graduation year. Those who joined GPR training within 6-10 years after leaving medical school are 22 (31%).

Q. 2: Sex

There are 20 (28%) female and 6 (8%) male from first year GPRs respondents and 28 (39%) female and 17 (24%) male GPR respondents from final year training. Total representation of female respondents is 67% (48 out of 71) compared to 33% male,

Q. 3: Age

More than 60 percent of the total GPRs belong to the age group of 25 years to 30 years, which mean that majority of them, are in this age range. Since many of the respondents have not entered their correct age, exact analysis is difficult. But it can be understood that all the respondents fall in the age category between 25 years and 35 years as the total percentage of representation in this age group is 76%.

Q.4: Which HSE region do you work in?

Table-1. HSE region in Palliative care training.

More than 35 percent of the respondents belong to Dublin Mid Leinster. After Dublin more responses are from the north western region from where more than 30 percent of the responses came.

Q. 5 to Q. 9 Training in Palliative care.

The questions are related to the duration of palliative care training, location of training, previous experience, and its comparison with present training. It is one of the major areas of assessment as the aim is to find out how GPRs are exposed to palliative care training in Ireland. The respondents were asked to report number of months of training received, training location, and their previous experience in palliative care vide questions 5 to 9.

Q. 5: Whether in 1st year or 2nd year GPR’s training

Among the respondents, 19 are in first year and 52 are in second year of their training.

Q. 6: Have you received specific palliative care training?

In order to know whether the Respondent GPRs are getting training in the palliative care, their response has been collected.

Figure 3. Number of months received palliative care training.

HSE region in Palliative care training.

72% of GPR’s did not receive the palliative care training.

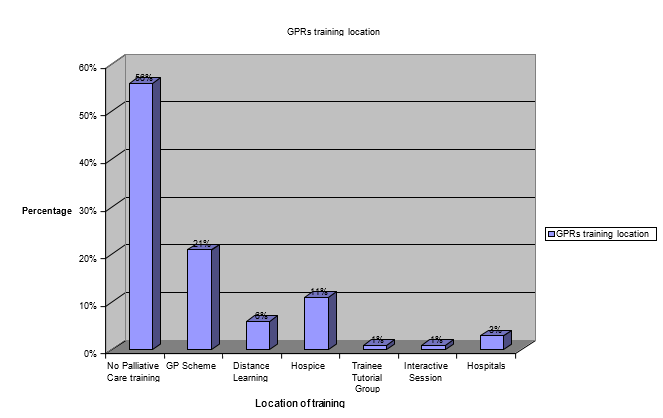

Q. 7. Where was this training based at?

The responses of the respondents regarding the training they received were collected and are depicted in the figure 4 below.

It shows that 56 percent of the GPRs have not received any training. The remaining percent of the respondents have received training through various methods like through GP scheme, distance learning, hospice, from trainee tutorial group, through interactive sessions and also from the hospitals in which they are working.

Q. 8: Did you have any previous experience in palliative care before the GP Scheme?

The GPR’s were also asked whether they are having any previous experiences in the palliative care, and the responses are presented in the figure 5 below.

About 79 percent of the respondents did not have any previous experiences in the palliative care. Only 20 percent of the GPRs responded that they had some experience in treating the cancer patients through palliative care.

Q. 9: If you received formal training in the GP scheme, how well do you perceive this training?

GPRs perceptions regarding the training they have received have been analysed and presented in the figure below.

It could be seen that majority of the respondents that is about 39 percent of the respondents have not received any training. The perception of the respondents who have received training is analysed and it is found that even after receiving the training eight percent of the respondents have poor knowledge about the palliative care. Only 11 percent of the respondents have fair knowledge about the palliative care after the training, and 12 percent of them have very good perception about the training in the palliative care.

The chart shown below depicts a graphical representation of the perception of the respondents regarding the training they received.

Q. 10 to 11: Knowledge of Pain and other symptoms control rating

This part covered self assessment in knowledge of pain control rating and knowledge in control of other symptoms rating. The information was elicited through the questions below.

Q. 10: From your training how would you rate your knowledge of pain control?

The respondents are rated with regard to their knowledge in pain control after receiving the training.

Q. 11: How would you rate your knowledge in control of symptoms other than pain in cancer patient example; Respiratory symptoms?

The response of the GPRs regarding the knowledge they possess in controlling the symptoms other than the pain in the cancer patients is presented in the table below

Table 2 knowledge of other symptoms.

The table shows that majority of respondents, that is 39% of them have a fair knowledge and 33 % have good knowledge regarding the other symptoms the patients have other than pain. But 15 percent of the respondents have poor knowledge about the symptoms other than the pain of the cancer patients

Q. 12 to Q. 18: Drug of choice in pain control

Control of pain and selecting appropriate dose of opioid and correct analgesics that can provide pain relief is crucial in palliative care. Questions from 12 to 18 covered drug of choice for cancer pain depending on the severity, use of opioids other than analgesic drugs, dosage of opioids to be used in the event of increasing pain symptoms, treatment of bone pain due to tumour involvement, knowledge of syringe driver and confidence of using it, and drugs that can be delivered subcutaneously with syringe driver.

In order to facilitate comparison of responses of GPRs with valid expert comments to get unbiased results from the study responses from ten palliative care consultants were also obtained for the same questions. For this purpose questionnaire had been sent to the above ten and their responses analysed. The responses of the GPR’s will be compared with the responses of the palliative care consultant’s answers to understand the GPR’s level of knowledge in drug use for pain control.

Q.12: What is your drug of choice for a cancer patient with pain?

Mild pain management response

Drug of choice for the cancer patients is analysed in detail. The opinion of GPRs for the treatment of mild pain for the cancer patients is presented in the Table below

Table 3:

The response was compared with the recommendation of palliative care consultants. Nine of the ten palliative consultants recommended paracetamol/NSAIDs as the correct answer for the mild cancer pain, whereas one palliative care consultant recommended paracetamol/NSAIDS+adjuvant for treating mild pain. According to World Health Organisation also the treatment for mild pain is non-opioids + adjuvant; Thus 48 GPRs (67.60%) correctly answered according to World Health Organisation classification analgesic ladder and in tune with the recommendation of majority of consultants.

Moderate pain management responses

The Drugs used in the cancer patients with moderate pain is studied and the response of GPRS is presented in the Table below.

Table 4:

To this question eight consultants preferred NSAIDs/weak opiods/ low dose opioids, one consultant responded as paracetamol+NSAIDs + strong opioids, and other one responded as NSAIDS/weak opiods/low dose opiods +adjuvant. According to the WHO classification treatment for severe pain is Opioid and plus or minus non opioids +/– adjuvant. The GPRs response in this study meeting WHO classification is 19(weak opiods) +12(NSAIDS’ with weak opiods) +5(paracetamol with mild opiods) =36 (50.70%).

Severe pain management responses

The responses of the GPRs regarding the drugs suggested for the severe cancer pain are being presented in the Table below.

Table 5.

For this question nine consultants preferred strong opioids, and one consultant opted paracetamol +NSAIDs at all time and strong opiods. WHO classification states that treatment for severe pain is opioid +– nonopiods+– adjuvant. The following reponses were in agreement with the consultant panel responses. They are Morphine (21), MST (12), strong opiods (22), Butrans/Durogesic Patch (4), and other strong opiods and adjuvants (7). The total number of matched doses came to 66 (92.95%). This indicates very good knowledge of severe pain management among GPRs

Q. 13: When you give strong opiods do you also include other non-analgesic medication? If yes please identify.

Nine consultants opted laxative and antiemetics, one consultant responded laxatives and other adjuvant depending on clinical consideration. According to palliative care formulary 3 and Oxford Test book of palliative care, laxatives are routinely prescribed to prevent constipation and antiemetics to prevent vomiting.

The level of knowledge here varied a lot. The agreement with the panel responses were for Laxatives + Antiemetics (39). The panel members also occasionally used either of the above as a stand alone drug. On the whole, there were 43(60%) agreements (39 Laxatives + 4 Antiemetics and laxatives).

Q.14: When your patient is on MST 60 mg bd and has further pain before his next dose what is your next course of action?

Figure 9

Recommendations of consultants were diverse as 6 palliative care consultants responded to give oramorph /morphine sulphate 20 mg, one consultant suggested severdol 20 mg, and in the event of repeated problem to increase the dose, one consultant suggested 10% of the total daily dose, one consultant suggested severdol 20 mg and assess the patient, other consultant suggested assess the cause of the pain and treat accordingly for controlling breakthrough pain. According to WHO the correct response is oramorph/ severdol 20mg, but it all depends on clinical scenario.

The knowledge level of the GPRs in this area is extremely poor. On the whole, only 17(23%) responses tallied with the ones given by the palliative care expert panel. This was for Severdol/morphine/.Morphine sulphate /oramorph 20 mg only. None of the other response was in agreement with the practices followed by the members of the expert panel or the WHO recommendation. Only 24% of the GPRs were correct to manage the situation when the patient is already on MST 60 BD and has pain before the next dose is due.

Q. 15: What treatment would you advise for bone pain due to tumour involvement?

Since different combination of methods are used to reduce bone pain the response of the consultants also are not alike. According to Oxford text Book of palliative care and WHO radiotherapy, opioids, NSAIDs, and Bisphosphonates are recommended to manage such conditions.

On analysis of GPRs responses it appears that the level of knowledge of those who knew the answers are 20 (28%). But the number of GPRs who do not know what to do in the case of bone pain management due to tumour involvement came up to nearly 17% (12 did not know the answer) of the total responses.

Q.15 to 18: Knowledge of Syringe drive

Confidence in using syringe drive, opioid preference in syringe drive, dose of opioid to cover 24 hours course of sedation, and appropriate drug that can be delivered subcutaneously with a syringe driver without tissue reaction has been explored through these questions.

Q. 16: How confident are you in using a syringe driver?