Executive Summary

The present project sought to explore the factors influencing turnover intentions of nurses working for the Ministry of National Guard. The study aimed to collect data on the drivers of nurses’ turnover intentions, thus identifying predictors of turnover intentions. The factors explored in the research were organisational, personal, and related to the work environment.

The study focused on a sample of staff nurses working at the National Guard Hospitals and used questionnaire as the primary method of data collection. The results confirm the relationship between turnover intentions of nurses and some organisational and work environment factors, including pay equity, organisational commitment, job satisfaction, leadership and promotional opportunities. Individual characteristics and alternative employment opportunities were not related to nurses’ turnover intentions.

The study highlights some turnover antecedents in the selected setting. The results can be used by the organisation’s management to develop retention strategies.

Factors Influencing Turnover Intentions of Nurses Working for the Ministry of National Guard’s Hospitals

Introduction

Turnover is a critical issue for any organisation since it affects the quality and availability of the workforce. High turnover can lead to various organisational problems, including poor quality of services or products. Studying the antecedents of turnover can help organisations to make changes that would prevent employees from leaving, retain valuable talents and enhance staffing ratios.

Turnover intentions are proven to be the primary predictor of turnover, and the factors influencing turnover intentions have been widely studied over the past decades. Scholars showed that turnover intentions are often associated with a combination of factors, including personal, organisational, and work-related, and that some of these factors can be addressed by organisations to enhance retention rates (Nei, Snyder & Litwiller, 2015).

In the healthcare sector, turnover is a particularly important concern because it affects care provider to patient ratios. Organisations with high turnover face the risk of having an inadequate number of care providers per shift, which impairs the quality of care provided to patients and threatens their health outcomes (Nei, Snyder & Litwiller, 2015).

Turnover among nurses presents a particularly important concern for medical organisations since here are evident shortages of qualified nurses all around the world, including in the United Kingdom, where there are currently over 40,000 nursing vacancies (Royal College of Nursing, 2020). Nurses perform a variety of duties that support operations in healthcare facilities, and thus they are instrumental in providing high-quality patient care. Decreasing nurses’ turnover intentions would help hospitals and clinics to reduce actual turnover and retain more nurses.

In order to achieve this goal, it is crucial for healthcare organisations to develop a thorough understanding of the issues that cause nurses’ intentions to quit. Addressing the root causes of high turnover intentions can help facilities to meet retention goals while also enhancing the organisational environment and improving staff’s commitment to the organisation (Nei, Snyder & Litwiller, 2015).

At the same time, healthcare organisations differ a lot in terms of their operations and internal environments; therefore, the results of past studies cannot always be generalised to medical facilities experiencing high turnover intentions now.

The aim of the present study was to examine the factors influencing the turnover intentions of nurses working in the Ministry of National Guard hospitals. The first objective was to study personal, organisational, and work environment factors that cause nurses’ intentions to leave the organisation. The second objective was to provide effective recommendations to the organisation’s management based on the results. It was anticipated that the project would contribute to the performance of human resources in the National Guard Hospitals while also enhancing the quality of care provided to patients and patient satisfaction through improved nurse-to-patient ratios.

Further sections of the report will present a literature review linking turnover intentions to other organisational and workforce characteristics, a summary of research methods used, an overview of the results of data analysis, a discussion of the study’s outcomes and limitations, conclusions and evidence-based recommendations for the selected organisation.

Literature Review

Key Terms

Turnover is defined as “the cessation of membership in an organization by an individual who received monetary compensation from the organization” (Demirtas and Akdogan, 2015, p. 62). The turn is typically applied to situations where employees withdraw from the organisation willingly due to organisational, job-related or personal reasons (Demirtas and Akdogan, 2015).

Turnover intentions precede turnover decisions and are thus of interest to researchers. Turnover intentions can be defined as employee’ cognitive thinking and planning processes related to withdrawal from the organisation (Demirtas and Akdogan, 2015).

Early Research on Turnover and Turnover Intentions

Employee turnover has been an important topic in management research for the past century. Early research on employee turnover dates back to the 1920s. Original scholarship in the area focused on predicting employee turnover by examining its correlates. For instance, a study by Bills (1925) showed employees whose fathers are in skilled professions or have small businesses quit more often than other workers. Descriptive studies centred on turnover patterns in organisations continued further, and more attention was dedicated to individual correlates of turnover in the 1940s (Hom et al., 2017).

Predicting turnover became an essential topic in research, with multiple studies focusing on validating tests to evaluate turnover intentions and the likelihood of leaving (Hom et al., 2017). Based on research, scholars began proposing models and frameworks to explain turnover in relation to other factors. For instance, Porter and Steers (1973) modified Vroom’s Expectancy Theory to explain turnover in terms of workers’ unmet expectations.

Later, Price (1977) presented a model of turnover wherein actual turnover was related to job satisfaction through turnover intent and with perceived alternative employment opportunities. An extended version of the causal model was proposed in 2001, linking turnover to more organisational and job-specific variables (e.g., job involvement, positive/negative affectivity, job stress, distributive justice, autonomy, etc.) (Price, 2001).

In turn, Mobley et al. (1979) argued that the relationship between job satisfaction and turnover was motivated by the utility and that people can stay in their jobs despite being dissatisfied if the perceived utility is high (Mobley et al., 1979). On the whole, early research on employee turnover showed the complicated relationship between turnover and individual and organisational factors, necessitating further examination of the topic.

Turnover in Nursing

Turnover has a significant effect on healthcare organisations because they need to maintain adequate staffing levels to avoid the deterioration of care quality (Alotaibi, 2008). Hence, various scholars considered the healthcare context and nurses specifically in turnover research. Based on scholarly data, turnover intentions of nurses are impacted by job satisfaction, promotional opportunities, working conditions, relationships with co-workers and leadership (Ayalew et al., 2015; Estryn-Behar et al., 2010; Irvine and Evans, 1995).

Demographic factors and tenure were also proven to be important in turnover decisions by Ayalew et al. (2015). Furthermore, studies have also shown that nurses’ turnover intentions can be related to organisational support, which mediates their commitment (Akremi et al., 2014). Some scholars have noted that turnover among nurses can also be traced back to individual difficulties, such as burnout and job stress experienced by nurses (Hoff, Carabetta and Collinson, 2019). As will be shown in further sections of the literature review, these findings are comparable with those related to other occupations.

Turnover and Work Environment

In the context of this project, the work environment is taken to mean a combination of factors, such as job characteristics, pay equity, promotional opportunities, workload and related factors. Both individually or collectively, these factors have been studied as possible antecedents of turnover and turnover intentions. For example, job characteristics and workload were found to predict turnover intentions of workers in various occupations (Alexander et al. 1998; Baernholdt and Mark 2009; Bjorvell and Brodin 1992; Takase et al. 2009; Shader et al., 2001; Sherman, 1989).

Research by McFadden and Demetriou (1993) also highlighted the influence of pressure and physical comfort on turnover. Pay equity and benefits also proved to be a prominent factor relating to turnover, reflecting earlier theories or job utility (Ali, 2008; Bryant and Allen, 2013; Singh and Loncar, 2010; Vandenberghe and Tremblay, 2008).

Another important job environment factor that has been studied in relation to turnover is job satisfaction. Various scholars focused on conceptualising this relationship and examining its influences in practice, such as Hulin (1968), Atchison and Lefferts (1972), Porter et al. (1974), Mobley (1977) and Dittrich and Carrell (1979). Most of the researchers agreed that there is a significant negative correlation between an employee’s level of job satisfaction and their intentions to quit their job voluntarily.

This argument was supported in later research (Carsten and Spector, 1987; Farrell and Rusbult, 1981; Shore and Martin, 1989; Tett and Meyer, 1993; Van Dick et al., 2004). More recent studies on job satisfaction and turnover typically examine specific employment settings or worker populations and also offer support to the theory (Abou Hashish, 2017; Chen et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2016; Lu et al., 2016; Lu and Gursoy, 2016). In general, research allows suggesting a rather strong negative link between work environment factors, including job satisfaction and characteristics, and turnover intentions.

Hypothesis 1: There is a negative correlation between workers’ perceptions of work environment and their turnover intentions.

Organisational Factors

Similarly, organisational factors have been featured consistently in turnover research. Based on early research, Mowday, Porter and Steers (1982) argued that organisational commitment was a significant predictor of turnover, with high levels of commitment reducing turnover intentions and actual turnover. Still, earlier research showed substantial variations in the results, failing to provide a stable basis for the theory (Mathieu and Zajac, 1990; Randall, 1990; Werbel and Gould, 1984).

Cohen (1993) states that variations in research findings can be caused by both methodological inconsistencies and differences in age, tenure and other characteristics of employees. Blau and Boal (1987) also included job involvement in their theory of turnover, showing how various combinations of job involvement and commitment can result in differences in turnover intentions.

More recent empirical research on the topic highlighted that organisational commitment influences actual turnover and turnover intentions in various cultural and professional contexts, although there are discrepancies in the strength of the relationship (Chen and Francesco, 2000; Joo and Park, 2010; Mosadeghrad, Ferlie and Rosenberg, 2008; Kim, 2007; Ponnu and Chuah, 2010; Tarigan and Ariani, 2015).

Factors related to leadership and social interaction, such as supervision, perceived organisational support and co-worker relations proved to be linked with turnover in studies by Katz and Tushman (1983), Leonard (1987), Mathieu and Babiak (2016) and Sherman (1989), among others. In all of these studies, workers’ assessment of the identified organisational factors were negatively related to their turnover intentions. Hence, the second hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 2: There is a negative correlation between workers’ perceptions of organisational factors and their turnover intentions.

Turnover and Individual Factors

Some scholars have also identified a relationship between individual factors and employee turnover intentions, both in nurses and in other populations of workers. For instance, age, qualifications, years of service, and income were negatively related to turnover intentions in multiple studies (Agyeman and Ponniah, 2014; Samad, 2006; Tai, Bame and Robinson, 1998).

Hence, younger workers with lower qualifications or income and fewer years of service were more likely to have high turnover intentions than their older, more qualified colleagues with a higher income level. Similarly, marital status and the number of children were considered to influence turnover intentions and decisions (Arnold and Feldman, 1982; Samad, 2006; Tai, Bame and Robinson, 1998). Based on these results, it was suggested that individual characteristics of nurses will impact their turnover intentions.

Hypothesis 3: There is a negative relationship between age, qualifications, income, work experience, and turnover intentions among nurses.

Turnover and Alternative Employment Opportunities

Alternative employment opportunities are also hypothesised to be related to turnover intentions and actual turnover. This theory relates to the concept of job utility, as mentioned by Mobley et al. (1979). It proposes that employees are more likely to quit voluntarily if they have alternative opportunities that are better in terms of important factors, such as job characteristics, promotional opportunities, pay and benefits and work environment (Hulin, Roznowski and Hachiya, 1985).

Research on the topic produced empirical support for the theory, showing that having good chances of employment or a lucrative offer from another company can prompt workers to quit (Gerhart, 1990; Kirschenbaum and Mano-Negrin, 1999; Laker, 1991; Mano-Negrin and Tzafrir, 2004; Rainayee, 2013). The role of alternative job opportunities in predicting turnover is vital to practitioners because it affects the retention of talented, high achieving individuals who contribute to corporate performance (Lang, Kern and Zapf, 2016; Lang, Kern and Zapf, 2016).

Still, there is some evidence that the effect of alternative opportunities on turnover can be mediated by internal career prospects or other organisational factors, such as commitment and work environment (Gerhart, 1990; Lang, Kern and Zapf, 2016; Rainayee, 2013). In the context of the study, these variables were not addressed, and thus the hypothesis was based on scholarly results suggesting a positive relationship between alternative employment opportunities and turnover.

Hypothesis 4: There is a positive correlation between workers’ of alternative employment opportunities and their turnover intentions.

Summary and Theoretical Framework

On the whole, employee turnover has been a popular topic in business management research since the first half of the twentieth century. Continued studies of the antecedents of employee turnover allowed formulating conceptual models and framework that explain its relationship to various individual, job-related and organisational factors.

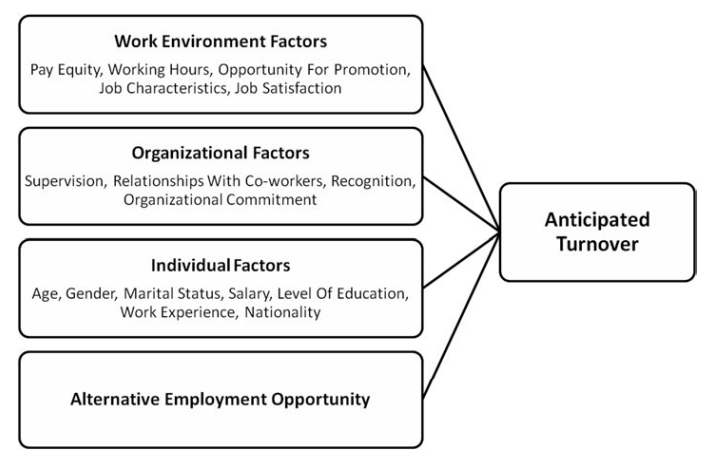

In general, research on the topic highlights the importance of work environment, organisational commitment, organisational factors, individual factors and alternative employment opportunities in predicting turnover intentions and real turnover. Hence, the model of anticipated turnover by Al-Ahmadi (2014) was used as the theoretical framework for this study (Figure 1). Although the literature review did not identify any significant gaps that the study could fulfil, the research will contribute to management practice in the organisation by reviewing actual turnover antecedents evident in the workplace.

Research Methods

Research Aims and Hypotheses

The aim of the present study was to examine the factors influencing the turnover intentions of nurses working in the Ministry of National Guard hospitals. By studying turnover antecedents in this context, the research generated data to support staff retention and provide recommendations as to how the organisation could target the problem. Based on the theoretical framework offered by Al-Ahmadi (2014), it was possible to formulate four hypotheses for the study.

First of all, the theoretical framework implies that work environment factors, including pay equity, working hours, opportunities for promotion, job characteristics, and job satisfaction will influence nurses turnover intentions (Al-Ahmadi, 2014). Consequently, the first hypothesis was that work environment factors predict nurses’ turnover intentions.

Secondly, organisational factors, including supervision, relationships with co-workers, recognition and organisational commitment were expected to be connected to employee turnover, with positive perceptions of these factors decreasing turnover intentions among nurses (Al-Ahmadi, 2014).

The third hypothesis concerns individual factors, for which there was some evidence of a correlation with turnover intentions (Al-Ahmadi, 2014). For instance, prior scholarship suggests that nurses’ intentions to leave are lower when they have commitments to their families, and thus marital status and age could be correlated with turnover intentions (El-Jardali et al., 2009; Larrabee et al., 2003, Rambur et al., 2003). Additionally, nurses who had more work experience ere expected to be less intent to quit their position (Chan et al., 2009; Stewart et al., 2011). Hence, the third hypothesis for the study is that personal factors will predict nurses’ turnover intentions.

Finally, alternative employment opportunities were addressed based on previous research, as they have shown to be correlated with turnover intentions. Therefore, the fourth hypothesis was that nurses’ perceptions regarding alternative employment opportunities will positively influence their turnover intentions.

Research Design

The choice of the research design was based on the context of the study and its key goals. Quantitative research was perceived to be more useful than alternative methods because of its benefits. According to scholars, quantitative methods allow identifying statistically significant trends and relationships based on respondents’ answers (Ghauri, Grønhaug and Strange, 2020; Maylor, Blackmon and Huemann, 2017).

Quantitative research also enables gathering larger volumes of data, which was important in this study due to the wide range of variables considered (Ghauri, Grønhaug and Strange, 2020; Maylor, Blackmon and Huemann, 2017). Survey design is beneficial because it takes less time for subjects to provide data, and they can do it in their free time by accessing a survey on the Internet, resulting in higher response rates. Therefore, the selected methodology and design fits the goals and context of the study entirely.

Data Collection

In order to collect the data, the Ministry of National Guards hospitals were contacted for permission. Once it was granted, the researcher used random sampling to select 112 nurses from the total population of over 1000 potential participants. While this sample size is rather small for quantitative research, random sampling helped to ensure that it would be representative of the nursing workforce in the organisation (Maylor, Blackmon and Huemann, 2017).

Random sampling was chosen because it helps to reduce the risk of bias, which is typically prominent in studies with non-probability sampling. Random sampling addresses this risk by ensuring that subjects are selected regardless of their physical, professional or other qualities. Thus, this type of sampling helps to create a representative study population.

Due to the wide variety of the variables included, the study relied on a combined instrument used by Al-Ahmadi (2014). In their research, the author used items related to organisational, work environment, alternative employment and turnover measures proposed by previous scholars (Hinshaw and Atwood, 1983; Peters, Jackofsky and Salter, 1981; Porter et al., 1974). The survey was located on a temporary web page and distributed to nurses’ emails after they agreed to participate in the study. The choice of this data collection method was justified by the need to use instruments with proven validity and reliability.

Data Analysis

In each of the tests, turnover intentions were set as the dependent variable. The number of independent variables was a lot higher, and they included age, work experience, weekly salary, job significance, autonomy, variability, challenge, pay equity, working hours, promotional opportunities, job satisfaction, leadership, work groups, organisational commitment, recognition, and alternative employment opportunities.

Most of these variables were measured using the instruments described above on a five-point Likert scale, except for weekly salary, age, and work experience, which were measured in years and British pounds. For variables where the instruments contained more than one question, average figures were used in the analysis. Each independent variable was tested to determine its influence on turnover intentions of the participants.

Regression analysis was selected as the primary method of data analysis since it shows whether or not the dependent variable is explained by the independent one and evaluates the strength of the predictive relationship (Ghauri, Grønhaug and Strange, 2020). Regression analysis was carried out in Microsoft Excel, where the data had been imported following the completion of the survey by all 105 nurses. Additionally, descriptive statistics were used to describe the personal characteristics of the sample, such as age, work experience, and income.

Validity and Reliability

Validity and reliability were addressed by using proven data collection instruments. On the one hand, the validity of the constructs used in the questionnaire was established based on previous researchers’ comments as well as by evaluating face validity (Al-Ahmadi, 2014; Hinshaw and Atwood, 1983; Peters, Jackofsky and Salter, 1981; Porter et al., 1974). The items considering demographic and personal characteristics were formulated in a conventional manner, thus also preventing confusion.

On the other hand, the reliability of the items was established based on past tests conducted by researchers who developed them. This allowed ensuring that the answers gained from the survey will be reliable and will not vary from one test to another, thus having high test-retest reliability (Ghauri, Grønhaug and Strange, 2020). Overall, concerns regarding the validity and reliability of the survey instrument were addressed appropriately, and the risk of bias or inaccuracy was minimised.

Ethical Considerations

Research involving human subjects is subject to multiple ethical considerations that should be addressed as part of the design. For instance, unethical research procedures can affect the participants’ right to privacy and confidentiality of the information and have significant negative consequences for them (Cascio and Racine, 2018).

Based on the design of the study, data privacy, confidentiality, and voluntary participation were the main ethical concerns associated with the research. In order to address these, the researcher made sure to provide participants with full information about the study and include an informed consent form on the title page of the survey. Also, the participants’ identifying data, such as names, phone numbers and addresses were not collected in the study.

Analysis and Results

Sample Description

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Sample Description.

The link to the online survey was distributed to 112 nurses, and 105 returned their answers by the deadline. The response rate was thus 93.75%, which was sufficient for the purposes of the present study. The majority of the nurses were female (n = 87, 82.8%), and the number of male nurses was 18 (17.2%). Descriptive statistics for numerical data are presented in Table 1. The mean age of nurses was 34.2 (SD = 7.46), with a range of 24 to 54. The mean work experience among nurses was 9.47 (SD = 5.08) and ranged from 2 to 22 years.

Weekly salary among nurses was £582.7 (SD = 91.5), with nurses earning from £450 to £760, depending on their work experience, qualifications and working hours. In terms of education level, most nurses (n=15, 50%) had a Bachelor’s degree. An Associate’s degree or its equivalent was reported by 7 nurses (23.3%), and 8 nurses (26.7%) had a Master’s degree or its equivalent.

The shares of married and unmarried nurses in the sample were almost equal, with 56 (53.3%) married and 49 unmarried nurses (46.7%). Most of the nurses in the sample were Philippine. On the whole, the sample fulfilled the goals of the study and allowed collecting enough data to analyse significant trends. Further subsections of the chapter will report on the results of testing each hypothesis.

Variable Description

The independent variables considered in the study were job characteristics (significance, autonomy, variability and challenge), pay equity, working hours, promotional opportunities, job satisfaction, leadership, work groups, organisational commitment, recognition and alternative employment opportunities.

The dependent variable was turnover intentions. Because the study was descriptive, none of the variables were manipulated. The results of descriptive statistics for non-individual variables are presented in Table 2. Turnover intentions were measured on a single-item scale rated on a Likert scale from 1 to 5. The mean turnover intention within the sample was 2.5, with a standard deviation of 1.14. The median and mode values were equal at 2.

Job characteristics evaluated as part of the survey were job significance, autonomy, variety and challenge. The scale included one item for each of these variables. Job significance had a moderately high mean value of 3.2, with a standard deviation of 1.23 and median and mode values of 3 and 4, respectively.

Autonomy scored a mean value of 2.7 with a standard deviation of 1.29. The median value here was 2, and the mode was 4. Job variety was generally even higher, at 3.13 with an SD of 1.48. The median and mode were 3.5 and 4. Challenge showed the highest average rating with a mean of 3.83 and a standard deviation of 1.44. The median and mode were both 5, indicating that most nurses viewed their job as very challenging.

Pay equity returned a mean value of 3.2 and a standard deviation of 0.9, indicating that most employees perceived the compensation to be fair. The median and mode answers were 3. Working hours were also viewed rather positively and had a mean of 3.1 with an SD of 1.42. The median and mode responses were 3.5 and 4, which suggests that nurses were generally reasonably satisfied with their working hours. With respect to promotional opportunities, the mean response was 3.57 (SD = 1.36).

The median and mode values were high at 4. Therefore, most nurses perceive their opportunities for professional development in the facility as positive. For job satisfaction, the results were also excellent, as the mean value for this variable was 4.2, with a standard deviation of 0.96. The median value was 4, and the mode was 5, indicating high satisfaction of the sample.

The evaluation of organisational variables was overall positive. Leadership was rated at a mean of 3.77, with mode and median of 4 and a standard deviation of 1.17. Work groups had the same median and mode answers, but the mean value was 3.4, with an SD of 1.10. Nurses’ organisational commitment was measured on a 10-item scale, and the results were re-calculated into a single average OC measure. The average organisational commitment had a mean of 3.8 (SD = 0.76), a median of 4 and a mode of 4.2.

Recognition was rated worse and showed a mean value of just 2.73 with an SD of 1.2 and mean and mode of 2. Finally, alternative employment opportunities were judged on a 2-item scale, and the results were also combined into a single measure. Average perceived alternative employment opportunities were rated at 2.84 with a standard deviation of 1.28, a median of 2.7 and a mode of 4.3.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics for Non-Individual Variables.

Turnover and Work Environment

The first hypothesis was that nurses’ perceptions of work environment factors, including job characteristics, pay equity, working ours, promotion opportunities and job satisfaction would influence turnover intentions negatively, decreasing it. Regression analysis was applied to each of the variables.

Firstly, job characteristics, such as significance, autonomy, variety and challenge, were evaluated. However, none of the variables showed a statistically significant result. The R2 values were 0.015, 0.006, 0.007 and 0.04 for job significance, autonomy, variety and challenge, respectively. Similarly, working hours did not influence turnover intentions with an R2 of 0.003.

However, other work environment variables showed a more significant relationship with turnover intentions. The result was the highest for pay equity, which had an R2 value of 0.24, meaning that about 24% of turnover intention responses were related to changes in pay equity perceptions. The result for promotional opportunities was somewhat lower, with an R2 value of 0.12. Lastly, job satisfaction could explain turnover intentions in about 14% of the cases (R2 = 0.143).

This means that the data gathered from nurses’ responses provided partial support for Hypothesis 1 based on data analysis using regression tests. Comparing the coefficient of determination for different variables suggested that job characteristics and working hours had minimal influence on turnover intentions, while factors including pay equity, promotional opportunities and job satisfaction had an essential impact on nurses’ turnover. This suggests that the organisation should consider improving nurses’ perceptions of these variables in order to retain more qualified nurses.

Turnover and Organisational Factors

Organisational variables, including leadership, work groups, organisational commitment and recognition, were also tested using regression calculations. Leadership had a coefficient of determination of 0.21 and an adjusted R2 of 0.18, indicating a strong link between nurses’ perceptions of management practices and their turnover intentions. In a similar way, organisational commitment was highly determinant of turnover intentions.

The R2 value for this pair of variables was 0.32, indicating a significant influence. Recognition was also related to turnover intentions of nurses in the sample (R2 = 0.14). Nevertheless, work group perceptions were not substantial in determining nurses’ turnover, with an R2 of 0.0002. This means that work groups did not influence nurses’ turnover intentions for the selected sample.

Hence, the second hypothesis was also supported only partially. The most significant relationship in this group of variables was identified between organisational commitment and turnover intentions. Leadership was an influencing factor in about 20% of the cases, whereas recognition affected the turnover intentions of about 14% of nurses who had responded to the survey. The relationship for all three pairs of variables was negative, meaning that better perceptions of organisational factors correlated with a lower result in terms of turnover intentions.

Turnover and Individual Factors

The influence of individual factors, including age, education level, work experience, salary, and marital status, on turnover intentions was also evaluated using regression tests. With respect to age, the relationship as not statistically significant and had an R2 value of 0.012. For education, the relationship was even weaker at R2 = 0.004. Like the previous factors, work experience did not predict nurses’ turnover intentions since the result showed an R2 value of just 0.02.

Regarding salary, the result was similarly weak (R2 = 0.012), indicating the lack of a connection. Finally, the marital status of nurses also was not determinant of their turnover intention as it had an R2 of 0.004. Consequently, the data provided no support for the second hypothesis of the study. This contradicts previous research evidence and the theoretical framework that formed the basis of the current study. Still, it is possible that the result was influenced by the sample size.

Turnover and Alternative Employment Opportunities

Alternative employment opportunities were expected to be positively related with turnover intentions. Nevertheless, the results did not support the hypothesis because the predictive values found in the analysis were too insignificant. The determination coefficient for this pair of variables was just 0.026, which was significantly lower than expected. Moreover, the correlation coefficient indicated a very weak negative relationship (-0.2), which also contradicted previous scholarship on the topic. Thus, the final hypothesis of the study was rejected in favour of the null hypothesis.

Discussion and Limitations

Discussion

Overall, the results of the analysis can be related to previous literature on the subject. The first hypothesis was partially confirmed, with factors such as pay equity, job satisfaction and promotional opportunities proving to have an influence on nurses’ turnover intentions. Pay equity had the most significant impact of all work environment factors, which reflects previous findings by Ali (2008), Bryant and Allen (2013), Singh and Loncar (2010) and Vandenberghe and Tremblay (2008).

In a similar manner, job satisfaction was related to employee turnover in other studies on the topic (Carsten and Spector, 1987; Huang et al. 2016; Lu et al., 2016; Tett and Meyer, 1993; Van Dick et al., 2004). Promotional opportunities were related to turnover in various studies, including those focusing on nursing specifically (Alhamwan and Mat, 2015; Carson et al., 1994). Consequently, the results of the study fit in with the rest of the research considering these influences.

Nevertheless, other work environment factors that were related to employee turnover in previous research did not have an impact in the studied setting. For example, job characteristics and work hours did not show a statistically significant relationship with turnover intentions despite having been found to predict turnover in other contexts (Alexander et al. 1998; Baernholdt and Mark 2009; Bjorvell and Brodin 1992; Takase et al. 2009; Shader et al., 2001; Sherman, 1989). This difference could be caused by the nature of nurses’ work, which offers little variation in terms of job characteristics between organisations.

With respect to organisational characteristics, leadership, work groups, organisational commitment and recognition were studied in the present research. The study found partial support for the hypothesis that workers’ perceptions of organisational factors influence their turnover intentions negatively.

Organisational commitment proved to be predictive of turnover in almost one-third of the cases, which supports the findings gathered by other scholars who have examined this pair of variables (Chen and Francesco, 2000; Joo and Park, 2010; Kim, 2007; Mathieu and Zajac, 1990; Tarigan and Ariani, 2015).

Leadership was the second most influential variable in the group, followed by recognition. Studies by Al-Ahmadi (2014), Katz and Tushman (1983), Leonard (1987), Mathieu and Babiak (2016) and Sherman (1989) indicate the relationship between these factors and turnover, both among nurses and in other employee populations. However, the relationship between work groups and turnover intentions was insignificant, which somewhat contradicts the results of these studies.

In terms of individual factors, the research found no support for the hypothesis that they impact turnover intentions. Age, work experience, salary, education level and marital status were all considered, but the results were statistically insignificant. This contrasts the findings of other scholars who studied nurses and other employee groups and found evidence of a correlation between employee demographics and their turnover intentions (Agyeman and Ponniah, 2014; Arnold and Feldman, 1982; Samad, 2006; Tai, Bame and Robinson, 1998). In future studies, it would be beneficial to examine the correlation in a larger population of nurses.

Lastly, the identified relationship between alternative job opportunities and turnover intention does not fit the theoretical framework and contrasts the results achieved by other scholars. For example, studies by Gerhart (1990), Kirschenbaum and Mano-Negrin (1999), Laker (1991), Mano-Negrin and Tzafrir (2004) and Rainayee (2013) all indicate the connection between alternative job opportunities and turnover intentions of staff in various settings. With application to nursing, Al-Ahmadi (2014) noted that alternative employment opportunities could influence turnover intentions since they encourage nurses to change their position for a better one. In the present case, this conclusion did not apply.

Limitations

Despite the fact that the results produced by the study are significant for the selected organisation, there were some limitations in the study that limit its application and the use of the results. Firstly, the research was conducted in Saudi Arabia, a country with a high context culture. This means that cultural factors can have an influence on various aspects of employment, including workers’ turnover intentions.

Secondly, the research took place in the Saudi Ministry of National Guard hospitals, which are public healthcare institution. Because the study did not include nurses working in private healthcare settings, the results cannot be extended beyond the public context.

Thirdly, the research used a quantitative design, which has a number of significant benefits but also comes with certain limitations. For instance, it was not possible to explore employees’ turnover intentions in greater depth than the research instrument allowed. Qualitative data collection methods, such as interviews, allow accessing more information, thus offering a more in-depth view of the participants’ attitudes, perceptions and decision-making process. Therefore, while the study shows the antecedents of turnover intentions in the chosen contexts, individual decision-making patterns may still vary.

Lastly, the sample of the study was limited to 105 participants, which was deemed sufficient for the practice setting. Still, gathering a larger volume of data would have helped to establish trends and relationships with a higher degree of certainty, thus adding to the methodological quality of the study. Besides these limitations, there were no factors that affected the study’s outcomes.

Conclusions

On the whole, the present study focused on the topic of turnover. This is a pressing issue in human resource management since it can affect various organisational outcomes, including HR expenses, performance and productivity. In nursing, turnover is particularly crucial because it influences staffing ratios in healthcare organisations and can reduce the quality of service provided to patients. Scholarly research on turnover typically focuses on its various antecedents, and there is a significant body of literature proving the relationship between turnover and different organisational and work environment factors.

The objectives of the study were twofold, and both of them were achieved as part of the project. On the one hand, the study helped to examine the factors influencing the turnover intentions of nurses working in the Ministry of National Guard hospitals in Saudi Arabia. The theoretical framework for the study included organisational, work environment and alternative employment factors impacting turnover intentions of nurses.

The study utilised a quantitative methodology with surveys as the primary data collection tool. The participants were 105 nurses working in the identified settings who completed the questionnaires. The data gathered as part of the research were analysed using linear regression to determine the factors that predict turnover intentions. The results of the study provided partial support of the hypotheses. Some organisational factors, such as leadership and organisational commitment, were found to be strongly predictive of nurses’ turnover intentions.

Similarly, the work environment, including job satisfaction, pay equity and promotional opportunities, impacted nurses’ willingness to leave their workplace. Alternative employment opportunities and individual factors showed no significant relationship to turnover, in contrast with other scholars’ results. In this way, the study achieved its first objective by identifying the factors influencing the turnover intentions of nurses working in the Ministry of National Guard hospitals.

On the other hand, the study also sought to provide recommendation for the organisation’s management that would help to address the problem of high turnover through meaningful action. The results also allowed fulfilling this objective by indicating the specific aspects of the organisation or the work environment that could be improved in order to reduce turnover intentions of nurses. Similarly, job satisfaction can be used to reduce turnover intentions of employees if higher levels of satisfaction are achieved through better rewards, recognition, or professional development opportunities. The recommendations are summarised in a separate section

Implications for Research

The work provided more data on the antecedents of turnover in nursing, thus contributing to the existing body of literature of the subject. The discussion shows that the results of the study can be related to many previous publications and support their conclusions. Hence, the research offered more evidence that organisational commitment, leadership, pay equity, promotional opportunities, and some other factors can predict employee turnover intentions.

For some variables, the findings contradicted the results of previous research, which is also an important implication. For example, the relationship between turnover and individual factors was not confirmed, along with the hypothesised effect of alternative employment opportunities. This contrasts previous findings, highlighting the need for more studies of these relationships in the context of nursing.

Based on the discussion, two critical suggestions for future research can be made. On the one hand, it would be helpful to examine the influence of alternative employment opportunities and individual factors on nurses’ turnover intentions using large samples from multiple contexts. This would help to clarify the results of the present study while also producing generalisable results. On the other hand, qualitative research of nurses’ turnover intentions would also be useful since it could explore individual decision-making factors that might moderate the effect that organisational, work environment and other factors have on nurses’ willingness to quit.

Implications for Management

The work sought to contribute to managerial decision-making in the selected organisation, so the results can also be applied to address nurses’ turnover in the Ministry of National Guard hospitals. The conclusions suggest that nurses in this context are greatly influenced by job satisfaction, pay equity, organisational commitment and leadership, meaning that improvements in these organisational aspects could help to reduce their turnover intentions.

The results of the study could thus be used to support interventions designed to minimise nurses’ turnover in the chosen setting This would help the organisation to reduce turnover among nurses, thus achieving better outcomes in terms of performance, quality of care, patient satisfaction and patient outcomes. In this way, the study could prove to be a valuable source of information for the managers of the chosen organisation.

Evidence-Based and Costed Recommendations

The second objective of the study was to support the Ministry of National Guard in addressing the issue of high turnover. The continuous shortage of nurses in the healthcare sector has prompted further research into nurse retention (Nei et al., 2015; Roche et al., 2015; Scammell, 2016; Schroyer et al., 2020). It is suggested that various retention strategies and programs can support companies in reducing voluntary turnover and improving the workforce (Aruna and Anitha, 2015; Cloutier et al., 2015; Haider et al., 2015; Hom et al., 2017; Kumar and Mathimaran, 2017; Radford and Chapman, 2015; Skelton, Nattress and Dwyer, 2019).

Hence, the results, along with prior research findings, were used to develop retention strategies to be applied in the organisation. Hence, the recommendations sought to build on these findings and influence retention by enhancing leadership, promotional opportunities, job satisfaction and pay equity, which were all significantly related to turnover intentions in the study.

The first recommendation is for the organisation to improve internal career development and planning. This is suggested because the results show a significant relationship between turnover and career development factors, including promotional opportunities, job satisfaction and pay equity. By enabling nurses to plan their professional growth within the organisation, it will likely achieve a reduction in nurses’ turnover intentions and their actual turnover. Furthermore, past research showed a positive impact of career development programs on employee retention in various settings (Long, Perumal and Ajagbe, 2012; Rahman and Nas, 2013; Shuck et al., 2014). The actionable plan for this suggestion is as follows:

- Develop a job description and candidate portrait for a career development specialist;

- Hire career development specialists to work in hospitals part-time;

- Create questionnaires for nurses to fulfil before and after sessions;

- Collect nurses’ feedback at three months and evaluate it;

- Create a full-time position if the feedback is positive.

The costs of implementing the first recommendation as suggested involve HR expenses needed for recruitment and selection, as well as the salary of a career development specialist. The primary assumption is that the persons hired by hospitals will be able to collect and analyse the feedback, and thus no other employees will need to be involved in the evaluation. Another assumption is that the salary offered by the organisation will be about £18,000, which is the average HR specialist salary in Saudi Arabia.

The annual cost flow for the first three months will equal £750 monthly for each part-time position, followed by £1,500 per month if full-time positions are introduced. The contingency for this recommendation is approximately 30% because it is possible that the selected workers will not be successful and further recruitment will be required. Costs that cannot be quantified are recruitment and selection costs since it is unclear if each hospital will recruit separately or by the head office.

Because the study also showed the vital effect of leadership on nurses’ turnover intentions, it is also recommended to provide leadership training to nurse leaders. Leadership training has been suggested to improve retention in healthcare settings, showing excellent results (Albrecht and Andreetta, 2011; Wallis and Kennedy, 2013). It is thus expected that leadership training will improve the behaviours of nurse leaders and contribute to retention. The plan for implementing this recommendation is as follows:

- Develop a list of crucial nurse leaders in three selected hospitals;

- Locate leadership training programs nearby and select one based on cost-benefit analysis;

- Conduct training for nurse leaders;

- Collect data on nurse turnover intentions at two months post-training;

- If effective, conduct training annually or bi-annually in all hospitals.

The cost of this plan will be relatively high, but it is expected to deliver results beyond retention by enhancing HRM practices to improve motivation, performance and other workforce characteristics. The costs that should be taken into account are training expenses and preparation costs, counted as hours spent by the organisation’s HR specialists on training selection, planning and evaluation.

If the average cost of leadership training in Saudi Arabia is assumed to be £500 per person, each hospital will pay £5,000 for each ten key nurse leaders annually or bi-annually as selected. The total costs depend on the chosen training course price and on the costs of involving HR specialists in the process, which cannot be quantified because it is unclear whether the implementation will be centralised or performed by each hospital separately. Hence, the contingency should be set at 20%.

It is expected that both recommendations will support the Ministry of National Guards in improving retention among nurses in its hospitals. This will help to achieve better quality of care and patient outcomes while also reducing HR expenses. Additionally, both leadership training and career development are expected to bring other benefits, such as improved commitment, motivation, perceived organisational support and productivity. These, in turn, will enhance the work environment and job satisfaction, which are essential to performance.

Personal Learning Statement

The project was instrumental for me in enhancing my knowledge of management and business research. Firstly, it allowed me to examine a real-life business issue by studying it in its context and producing recommendations that the management could apply to solve it. Secondly, it provided an opportunity to explore a wide range of literature on the subject of turnover, as well as on business research methods and instruments. Although the study did not highlight any learning needs, I believe that I would benefit from studying and practising qualitative and mixed research methods so that I could use these approaches freely in the future.

The main difficulty that arose during the project is that the initial sample size was not sufficient for the chosen methods of analysis. At first, the methodology included only one hospital in Saudi Arabia, and thus data for just 105 nurses were collected. After this limitation was highlighted, I had to contact other hospitals for more questionnaires to be sent to gather a larger sample size. This took time and effort but also taught me to examine various sample size options from the beginning to avoid this issue in the future.

In general, preparing the report helped me to better understand the process of business research. As part of conducting this project, I learned more about the methods used by other scholars and practised quantitative analysis to help the organisation in solving its issue. In the future, I would like to explore turnover intentions using qualitative or mixed methods since I believe qualitative data could help to gain more insight into the problem.

Reference List

Abou Hashish, E. A. (2017) ‘Relationship between ethical work climate and nurses’ perception of organizational support, commitment, job satisfaction and turnover intent’, Nursing Ethics, 24(2), pp. 151-166.

Agyeman, C. M. and Ponniah, V. M. (2014) ‘Employee demographic characteristics and their effects on turnover and retention in MSMEs’, International Journal of Recent Advances in Organizational Behaviour and Decision Sciences, 1(1), pp. 12-29.

Akremi, E. A. et al. (2014) ‘How organizational support impacts affective commitment and turnover among Italian nurses: a multilevel mediation model’, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(9), pp. 1185-1207.

Al-Ahmadi, H. (2014) ‘Anticipated nurses’ turnover in public hospitals in Saudi Arabia’, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(3), pp. 412-433.

Albrecht, S. L. and Andreetta, M. (2011) ‘The influence of empowering leadership, empowerment and engagement on affective commitment and turnover intentions in community health service workers’, Leadership in Health Services, 24(3), pp. 228-237.

Alhamwan, M. and Mat N. B. (2015) ‘Antecedents of turnover intention behavior among nurses: A theoretical review’, Journal of Management. & Sustainability, 5(1), pp. 84-96.

Ali, N. (2008) ‘Factors affecting overall job satisfaction and turnover intention’, Journal of Managerial Sciences, 2(2), pp. 239-252.

Alotaibi, M. (2008) ‘Voluntary turnover among nurses working in Kuwaiti hospitals’, Journal of Nursing Management, 16(3), pp. 237-245.

Arnold, H. J. and Feldman, D. C. (1982) ‘A multivariate analysis of the determinants of job turnover’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 67(3), pp. 350-360.

Aruna, M. and Anitha, J. (2015) ‘Employee retention enablers: generation Y employees’, SCMS Journal of Indian Management, 12(3), pp. 94-103.

Atchison, T. J. and Lefferts, E. A. (1972) ‘The prediction of turnover using Herzberg’s job satisfaction technique’, Personnel Psychology, 25(1), pp. 53–64.

Ayalew, F. et al. (2015) ‘Factors affecting turnover intention among nurses in Ethiopia’, Health Human Resources, 16(2), pp. 62-74.

Bills, M. A. (1925) ‘Social status of the clerical work and his permanence on the job’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 9(1), pp. 424 – 427.

Blau, G. J. and Boal, K. B. (1987) ‘Conceptualizing how job involvement and organizational commitment affect turnover and absenteeism’, Academy of Management Review, 12(2), pp. 288-300.

Bryant, P. C. and Allen, D. G. (2013) ‘Compensation, benefits and employee turnover: HR strategies for retaining top talent’, Compensation and Benefits Review, 45(3), pp. 171-175.

Carson, P. P. et al. (1994) ‘Promotion and employee turnover: critique, meta-analysis, and implications’, Journal of Business and Psychology, 8(4), pp. 455-466.

Cascio, M. A. and Racine, E. (2018) ‘Person-oriented research ethics: integrating relational and everyday ethics in research’, Accountability in Research, 25(3), pp. 170-197.

Carsten, J. M. and Spector, P. E. (1987) ‘Unemployment, job satisfaction, and employee turnover: a meta-analytic test of the Muchinsky model’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 72(3), pp. 374-381.

Chan, M.F. et al. (2009) ‘Factors influencing Macao nurses’ intention to leave current employment’, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18(6), pp. 893–901.

Chen, Z. X. and Francesco, A. M. (2000) ‘Employee demography, organizational commitment, and turnover intentions in China: do cultural differences matter?’ Human Relations, 53(6), pp. 869-887.

Chen, I. H. et al. (2015) ‘Work‐to‐family conflict as a mediator of the relationship between job satisfaction and turnover intention’, Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(10), pp. 2350-2363.

Cloutier, O., Felusiak, L., Hill, C. and Pemberton-Jones, E. J. (2015) ‘The importance of developing strategies for employee retention’, Journal of Leadership, Accountability & Ethics, 12(2), pp. 119-129.

Cohen, A. (1993) ‘Organizational commitment and turnover: a meta-analysis’, Academy of Management Journal, 36(5), pp. 1140-1157.

Dittrich, J. E. and Carrell, M. R. (1979) ‘Organizational equity perceptions, employee job satisfaction, and departmental absence and turnover rates’, Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 24(1), pp.29-40.

El-Jardali, F. et al. (2009) ‘A national cross-sectional study on nurses’ intent to leave and job satisfaction in Lebanon: implications for policy and practice’, BMC Nursing, 8(1), p. 3.

Estryn-Behar, M. et al. (2010) ‘Longitudinal analysis of personal and work-related factors associated with turnover among nurses’, Nursing research, 59(3), pp. 166-177.

Farrell, D. and Rusbult, C. E. (1981) ‘Exchange variables as predictors of job satisfaction, job commitment, and turnover: the impact of rewards, costs, alternatives, and investments’, Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 28(1), pp.78-95.

Gerhart, B. (1990) ‘Voluntary turnover and alternative job opportunities’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(5), pp.467-510.

Ghauri, P., Grønhaug, K. and Strange, R. (2020) Research methods in business studies. 5th edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Haider, M., et al. (2015) ‘The impact of human resource practices on employee retention in the telecom sector’, International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 5(1S), pp. 63-69.

Hinshaw, A. S., and Atwood, J. R. (1983) ‘Nursing staff turnover, stress, and satisfaction: models, measures, and management’, Annual Review of Nursing Research, 1(1), pp. 133–153.

Hoff, T., Carabetta, S. and Collinson, G. E. (2019) ‘Satisfaction, burnout, and turnover among nurse practitioners and physician assistants: a review of the empirical literature’, Medical Care Research and Review, 76(1), pp. 3-31.

Huang, Y. H. et al. (2016) ‘Beyond safety outcomes: an investigation of the impact of safety climate on job satisfaction, employee engagement and turnover using social exchange theory as the theoretical framework’, Applied Ergonomics, 55, pp. 248-257.

Hulin, C. L. (1968) ‘Effects of changes in job-satisfaction levels on employee turnover’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 52(2), pp. 122-126.

Hulin, C. L., Roznowski, M. and Hachiya, D. (1985) ‘Alternative opportunities and withdrawal decisions: empirical and theoretical discrepancies and an integration’, Psychological Bulletin, 97(2), pp. 233-250.

Irvine, D. M. and Evans, M. G. (1995) ‘Job satisfaction and turnover among nurses: Integrating research findings across studies’, Nursing Research, 44(4), pp. 246–253.

Joo, B. K. B. and Park, S. (2010) ‘Career satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intention’, Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 31(6), pp. 482-500.

Katz, R. and Tushman, M. L. (1983) ‘A longitudinal study of the effects of boundary spanning supervision on turnover and promotion in research and development’, Academy of Management Journal, 26(3), pp. 437-456.

Kim, M. R. (2007) ‘Influential factors on turnover intention of nurses; the affect of nurse’s organizational commitment and career commitment to turnover intention’, Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration, 13(3), pp. 335-344.

Kirschenbaum, A. and Mano-Negrin, R. (1999) ‘Underlying labor market dimensions of “opportunities”: the case of employee turnover’, Human Relations, 52(10), pp. 1233-1255.

Kumar, A. A. and Mathimaran, K. B. (2017) ‘Employee retention strategies: an empirical research’, Global Journal of Management and Business Research, 17(1), pp. 1-14.

Laker, D. R. (1991) ‘Job search, perceptions of alternative employment and turnover’, Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR), 7(1), pp. 6-15.

Lang, J., Kern, M. and Zapf, D. (2016) ‘Retaining high achievers in times of demographic change. The effects of proactivity, career satisfaction and job embeddedness on voluntary turnover’, Psychology, 7(13), pp. 1545-1562.

Larrabee, J. H. et al. (2003) ‘Predicting registered nurse job satisfaction and intent to leave’, Journal of Nursing Administration, 33(1), pp. 271–283.

Leonard, J. S. (1987) ‘Carrots and sticks: pay, supervision, and turnover’, Journal of Labor Economics, 5(4-2), pp. S136-S152.

Long, C. S., Perumal, P. and Ajagbe, A. M. (2012) ‘The impact of human resource management practices on employees’ turnover intention: a conceptual model’, Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, 4(2), pp. 629-641.

Lu, L. et al. (2016) ‘Work engagement, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(4), pp. 737-761.

Lu, A. C. C. and Gursoy, D. (2016) ‘Impact of job burnout on satisfaction and turnover intention: do generational differences matter?’, Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 40(2), pp. 210-235.

Mano‐Negrin, R. and Tzafrir, S. S. (2004) ‘Job search modes and turnover’, Career Development International, 9(5), pp. 442-458.

Mathieu, J. E. and Zajac, D.M. (1990) ‘A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates and consequences of organizational commitment’, Psychological Bulletin, 108, pp. 171-194.

Mathieu, C. and Babiak, P. (2016) ‘Corporate psychopathy and abusive supervision: their influence on employees’ job satisfaction and turnover intentions’, Personality and Individual Differences, 91, pp. 102-106.

Maylor, H., Blackmon, K. and Huemann, M. (2017) Researching business and management. 2nd edn. London: Macmillan International Higher Education.

McFadden, M. and Demetriou, E. (1993) ‘The role of immediate work environment factors in the turnover process: a systemic intervention’, Applied Psychology: An International Review, 42(2), pp. 97–115.

Mobley, W. H. (1977) ‘Intermediate linkages in the relationship between job satisfaction and employee turnover’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 62(2), pp. 237-240.

Mobley, W. H. et al. (1979) ‘Review and conceptual analysis of the employee turnover process’, Psychological Bulletin, 86, pp. 493–522.

Mosadeghrad, A. M., Ferlie, E. and Rosenberg, D. (2008) ‘A study of the relationship between job satisfaction, organizational commitment and turnover intention among hospital employees’, Health Services Management Research, 21(4), pp. 211-227.

Ponnu, C. H. and Chuah, C. C. (2010) ‘Organizational commitment, organizational justice and employee turnover in Malaysia’, African Journal of Business Management, 4(13), pp. 2676-2692.

Porter, L. W. and Steers, R. M. (1973) ‘Organizational, work, and personal factors in employee turnover and absenteeism’, Psychological Bulletin, 80, pp. 151–176.

Porter, L. W. et al. (1974) ‘Organizational commitment, job satisfaction and turnover among psychiatric technician’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 59(1), pp. 603-609.

Price, J. L. (1977) The study of turnover. Ames, IA: Iowa State Press.

Price, J. L. (2001) ‘Reflections on the determinants of voluntary turnover’, International Journal of Manpower, 22(1), pp. 600-624.

Radford, K. and Chapman, G. (2015) ‘Are all workers influenced to stay by similar factors, or should different retention strategies be implemented?: Comparing younger and older aged-care workers in Australia’, Australian Bulletin of Labour, 41(1), pp. 58-81.

Rahman, W. and Nas, Z. (2013) ‘Employee development and turnover intention: theory validation’, European Journal of Training and Development, 37(6), pp. 564-579.

Rainayee, R. A. (2013) ‘Employee turnover intentions: job stress or perceived alternative external opportunities’, International Journal of Information, Business and Management, 5(1), pp. 48-59.

Rambur, B. et al. (2003) ‘A statewide analysis of RNs’ intention to leave their position’, Nursing Outlook, 51(1), pp. 181–188.

Randall, D. M. (1990) ‘The consequences of organizational commitment: methodological investigation’, Journal of Organizational Behavior, 11(1), pp. 361-378.

Roche, M. A. et al. (2015) ‘The rate and cost of nurse turnover in Australia’, Collegian, 22(4), pp. 353-358.

Samad, S. (2006) ‘The contribution of demographic variables: job characteristics and job satisfaction on turnover intentions’, Journal of International Management Studies, 1(1), pp. 12-17.

Sherman, J. D. (1989) ‘The relationship between factors in the work environment and turnover propensities among engineering and technical support personnel’, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 2(1), pp. 72-78.

Shore, L. M. and Martin, H. J. (1989) ‘Job satisfaction and organizational commitment in relation to work performance and turnover intentions’, Human Relations, 42(7), pp. 625-638.

Shuck, B. et al. (2014) ‘Human resource development practices and employee engagement: Examining the connection with employee turnover intentions’, Human Resource Development Quarterly, 25(2), pp. 239-270.

Singh, P. and Loncar, N. (2010) ‘Pay satisfaction, job satisfaction and turnover intent’, Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, 65(3), pp. 470-490.

Skelton, A. R., Nattress, D. and Dwyer, R. J. (2019) ‘Predicting manufacturing employee turnover intentions’, Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science, 25(49), pp. 101-117.

Stewart, N. J. et al. (2011) ‘Moving on? Predictors of intent to leave among rural and remote RNs in Canada’, Journal of Rural Health, 27(1), pp. 103–113.

Tai, T. W. C., Bame, S. I. and Robinson, C. D. (1998) ‘Review of nursing turnover research, 1977–1996’, Social Science & Medicine, 47(12), pp. 1905-1924.

Tarigan, V. and Ariani, D. W. (2015) ‘Empirical study relations job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intention’, Advances in Management and Applied Economics, 5(2), pp. 21-42.

Tett, R. P. and Meyer, J. P. (1993) ‘Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: path analyses based on meta‐analytic findings’, Personnel Psychology, 46(2), pp. 259-293.

Van Dick, R. et al. (2004) ‘Should I stay or should I go? Explaining turnover intentions with organizational identification and job satisfaction’, British Journal of Management, 15(4), pp. 351-360.

Wallis, A. and Kennedy, K. I. (2013) ‘Leadership training to improve nurse retention’, Journal of Nursing Management, 21(4), pp. 624-632.

Werbel, J.D. and Gould, S. (1984) ‘A comparison of the relationship of commitment to the turnover in recently hired and tenured employees’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(1), pp. 687-690.