Background

The country’s seniors have commendable aims in wanting to be engaged, healthy, and energetic. However, how people really experience “old age” in the United States is not always consistent with how society views the term. Numerous contemporary assumptions about aging were founded on data that, in light of recent scientific advancements, is no longer accurate. It has become clear that the mentioned population needs some additional aid that the government can provide. The idea of this speech is to prove the necessity for US senior citizens to obtain free WIC benefits. This statement will be founded on the approach of debunking a number of myths related to the state of elderly people in the country. These misconceptions are that elderly people in the US have significant health, reside in nursing facilities not requiring additional healthcare benefits, and have no chance to reduce the risk of cognitive issues.

Inoculation

The first misconception is that US senior citizens demonstrate significant health conditions and do not require any assistance added to their current governmental preferences. In fact, eighty-two percent of older persons have two or more chronic conditions, and seventy-seven percent have three or more (American Psychological Association, 2020). As people get older, a greater percentage of them require assistance with daily tasks. Then, among those 65 and older, four chronic diseases – heart disease, cancer, dementia, and diabetes – account for over two-thirds of all fatalities each year. What is more, over 25% of Americans aged 55 and older have been infected with HIV, and this percentage is rising (American Psychological Association, 2020). The indicated issues can be addressed better if senior citizens will get free benefits – related to the healthcare access dimension – of WIC.

The second myth is that the majority of elderly Americans reside in nursing facilities, which reduces the necessity of obtaining free WIC benefits, given that senior citizens are already being cared for. However, only approximately 5 percent of elderly Americans currently reside in nursing facilities. It should be admitted that the proportion rises with age, going from 1.1 percent for those aged 65 to 74 to 3.5 percent for people aged 75 to 84 and 13.2 percent for people aged 85 and above (American Psychological Association, 2020). Nevertheless, the presented numbers show that many elderly people in the US are capable of residing in their homes. Thus, senior citizens do not tend to change their way of living considerably with age, but their health requires a greater extent of maintenance, which justifies the need to provide free WIC benefits.

The third myth is that there is no way to lower the chance of developing dementia and related diseases in elderly people in the United States. In fact, smoking, being overweight, having diabetes, hypotension, or depression all raise the chance of developing dementia (American Psychological Association, 2020). The same thing is about physical and mental weakness and inactivity – these elements can all be changed. Preserving cognitive abilities and maintaining general health can all be achieved by being cognitively and physically active, as well as by adhering to a healthy diet. WIC benefits imply the supply of healthy food and related education, which, again, seem to justify their free provision to senior citizens in the country.

Graph

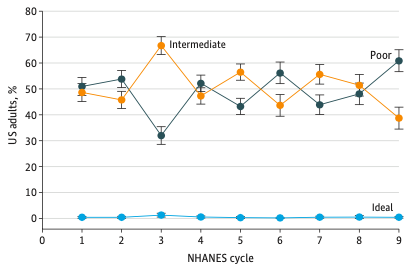

In the United States, a poor diet is a significant risk determinant for chronic illnesses, disabilities, and mortality. The presented graph allows the evaluation of dietary patterns among older individuals. It is essential given that senior citizens are the demographic group in the US with the greatest rate of growth. The percentage of older American individuals with an unhealthy diet grew dramatically from 50.9 percent to 60.9 percent, while the percentage of those with medium diet quality declined substantially from 48.6 percent to 38.7 percent (Long et al., 2022). The percentage of those with excellent diet quality remained continuously low during the periods of 2001-2002 and 2017-2018. Such a state of affairs reveals the fact that elderly people are much closer to diseases related to poor nutrition – that is likely to have fatal effects in their age – than it might seem. They require dietary benefits that WIC can provide them with.

Fear Appeal

Aside from the provided data, there is evidence that senior citizens are being treated inappropriately within the national healthcare system. In her interactions with healthcare professionals, retired assistant clinical professor of pharmacology Joanne Whitney, 84, frequently feels undervalued (Graham, 2021). Whitney arrived at the hospital with a serious anal fissure, a urinary tract infection, and screams of anguish. A young doctor responded to her request for Dilaudid, a potent drug that had previously assisted her, by saying that they did not hand out opioids to individuals who just seek them. Whitney was making that request to change a drug that was not helping her for eight hours, and her suffering did not stop (Graham, 2021). Such an attitude is inherent to numerous hospitals around the country and increases the risk of physical and mental states worsening considerably. It seems that senior citizens need not only additional free benefits of WIC but also reconsidering the healthcare system as a whole.

Call to Action

The claimed statements allow arguing in favor of providing elderly people in the US with free WIC benefits and even more. Why don’t we reconsider the healthcare system generally giving the main preferences to senior citizens? Then, isn’t it essential to broaden the WIC coverage to elderly individuals so that they could get the associated benefits for free?

References

American Psychological Association. (2020). Older adults’ health and age-related changes: Reality versus myth. Web.

Graham, J. (2021). ‘They treat me like I’m old and stupid’: Seniors Decry health providers’ age bias. KNN. Web.

Long, T., Zhang, K., Chen., & Wu, C. (2022). Trends in diet quality among older US adults from 2001 to 2018. JAMA Network Open, 5(3), 1–12.