Abstract

Purpose: To investigate the connection between adverse life events and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) development.

Method: Critical review of literature. Six key pieces of academic research are considered for an in-depth examination.

Findings: Studies focus on multiple links between affecting factors and ADHD. Demographic characteristics, comorbidities, parent mental illness, socioeconomic factors and negative life events are highlighted as contributors to ADHD development. Parent education is highlighted as a vital aspect of treatment. Caretakers of children with ADHD can change their parenting approaches in order to balance between autonomy and indulgence.

Conclusions: ADHD is closely tied to adverse events, including trauma, neglect, and criticism from family members. Parent training performed by mental health nurses should be expanded to include the assessment of parents’ distress and possible mental health concerns. Programmes should be flexible, offered in both individual and group formats.

Summary:

- There exist many causes of ADHD, including genetic and environmental.

- Children’s past events may influence their mental health.

- New: ADHD’s development is based on factors some of which can be influenced through education.

Introduction

Mental health nurses have to consider the complex nature of most conditions when working with patients. Such an issue as Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) may have severe consequences, and since quite often, people may have co-existing conditions, it is common for healthcare providers to support those with this problem and some other disorders (Thapar et al. 2013). While the previous medical advancements focused on the first of the mentioned causes, the latter two (childhood and family-related events) are becoming widely recognised as vital in not only diagnosing but also treating ADHD (Tarver, Daley and Sayal 2014). In fact, this shift from a medical towards personal explanation of the condition is one of the main controversies in discussing ADHD – it remains unclear to what extent parental styles influence the occurrence of the disorder (Bornovalova et al. 2013). Thus, mental health nursing should pay significant attention to how this approach to the condition progresses and in which ways modern practices utilize theoretical findings.

The condition in question is ADHD, a disorder that currently affects more than three per cent of all children around the world (Thapar et al. 2012). While it is often thought about as a childhood condition, it can continue into adulthood and significantly affect one’s everyday life, especially if it is left unmanaged. The main symptoms of ADHD are based on changes in one’s behaviour, which manifest constantly – a person with ADHD has difficulties controlling impulses and paying attention. This means that people with ADHD often lack patience in interacting with others, and their inability to focus can present as self-centred behaviour or impoliteness (Uchida et al. 2018). Such individuals have lowered concentration levels; they are restless or have a need to be active at all times (Uchida et al. 2018). In adults, ADHD may translate into what is perceived as high irritability, short temper, and a susceptibility to stress (Uchida et al. 2018). The management of ADHD can help such persons to live a balanced life.

New diagnostic approaches to ADHD identification have been focused on the exploration of predisposition to the disorder and the use of symptom-rating scales. For example, Grabemann et al. (2017) provided evidence for an innovative ADHD diagnosis method that retrospectively diagnosed the condition with the help of the Essen-Interview-for-school-days-related biography (EIS) that reduced the limitations of judgment bias and forgetting past events. This means that no external factors affect the objectivity of the problem perception and the ways of eliminating it.

The main reason to review impact of parental styles on people with ADHD lies in the necessity to provide individuals with ways of managing the condition apart from drug-based interventions. While pharmacological help for persons with ADHD is often required and helpful, it should not remain as the only option since it may not address possible underlying problems and lead to ineffective treatment or low adherence (Ghosh 2016). By investigating the effects of family and childhood experiences on the development of ADHD, a mental health nurse can contribute to the implementation of the latest evidence into practice.

Currently, the focus of therapeutic interventions for people with ADHD is children’s education and symptoms control. However, as the contemporary scholarly findings indicate, training and supporting parents is as important in preventing and managing the condition of their children as patient learning (Robin 2014). The intervention should be aimed at analyzing a genetic susceptibility to this disorder and assessing the factors causing the development of the problem (Yousefia, Far and Abdolahian 2011). In this case, the assessment of the influence of parental styles can be valuable due to the possibility of comparing behavioural factors in adults and children. Also, the analysis of the effectiveness of educational practices needs to be conducted to determine how communication and the evaluation of personal experience may prevent and minimise the manifestations of ADHD.

Methods

Multiple databases were employed in researching the literature on this topic. In order to source the most relevant evidence, CINAHL Plus, PubMed and Cochrane Library were used. Moreover, Google Scholar was utilised to collect information about the most recent available research and see additional data (Grewal, Kataria and Dhawan 2016). The use of these databases for researching topics related to mental health nursing can be explained by the fact that such sources as PubMed and CINAHL Plus contain many primary research studies on medical subjects. Cochrane Library offers reviews that establish evidence-based guidelines for practitioners that can be used internationally (Cooper et al. 2018). Finally, Google Scholar is a search engine that combines all databases and allows one to simplify the searching process and identify articles which would not be found otherwise.

The main keyword that describes the researched condition is ‘ADHD’ or ’Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder’. MeSH term for this entry is ‘Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity or ADHD’. The combination of the search terms through the use of ‘or’ is linked to Boolean search logical that allows to combine keywords with modifiers ‘and’, ‘or’, ‘not’ to produce relevant results. To narrow the topic, such suggested search builder options as ‘nursing and ADHD’, ‘ADHD not anxiety’, ‘ADHD not bipolar’, ‘rehabilitation and ADHD’ and ‘therapy and ADHD’ were added. Furthermore, as the main topic is related to the family impact on ADHD, the research was expanded to use MeSH terms ‘child adverse events and ADHD’, ‘psychological trauma and ADHD’, and ‘ADHD and parent-child relations’. For Google Scholar, search options were ‘ADHD and childhood trauma’, ‘ADHD and negative events’, ‘ADHD and parent influence’.

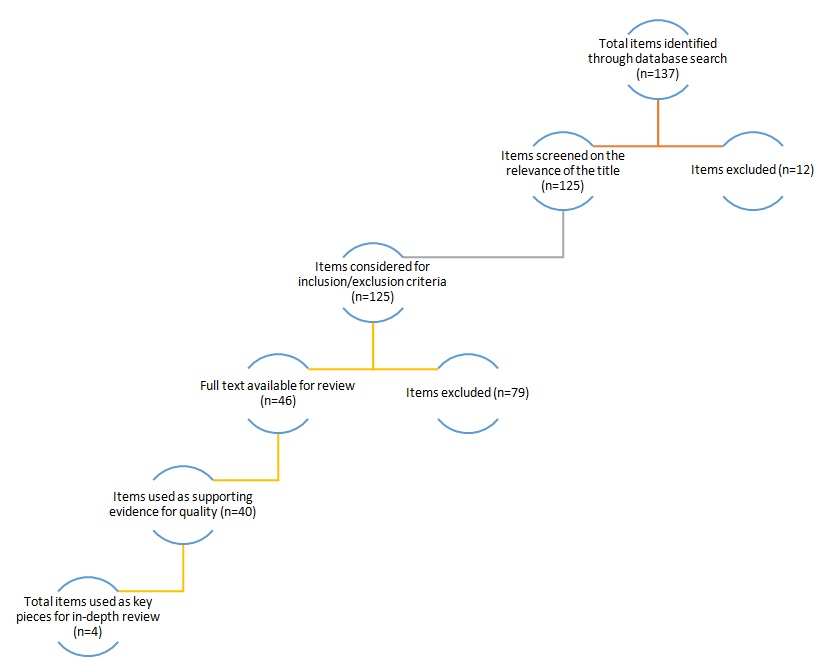

Studies were included if they discussed the influence of parents or adverse childhood events on people with ADHD. Both qualitative and quantitative research was accepted for review to expand the understanding of the issue. Furthermore, studies that were published 10 or more years before the current evaluation were excluded to ensure that recent, relevant, and contemporary information was drawn on. Thus, the inclusion criteria were: published within the last 10 years, primary research, qualitative or quantitative design, focus on the connection between parents and children with ADHD. During the first phase of the search, 137 articles were identified on all used databases. Using the review and inclusion/exclusion criteria, 46 studies were collected – they all considered various aspects of the relationship between childhood adverse events, trauma, parenting and ADHD. The main themes were identified, and four key pieces of literature were chosen for an in-depth review. The full process and the results can be seen in the flow diagram in Appendix A.

The articles were selected due to their rigorous and relevant research into the relationship between parental behaviour and children’s development of ADHD. All approved studies were assessed for quality and showed high reliability of evidence. The critiquing framework that will be used in the literature review is based on the tool developed by Rodgers (2011). This tool was chosen because of its comprehensive look on the aspects of research that together make up a framework for research studies formation. It includes the assessment of the following aspects: research problem, literature review, theoretical framework, hypotheses, design, sample, variables, data collection, data analysis and results, discussion and findings’ interpretation and applications to public health.

The main limitations of this review are based on the scope of researched sources – as it is conducted on six key pieces, the knowledge provided in the end will depend on the articles’ quality. The main themes found during the course of the review are tied to genetics and demographic characteristics, comorbidities of people with ADHD, socioeconomic characteristics of families, PMH as well as negative events with a primary focus on abuse. In terms of including a Korean study, there is an advantage of approaching the topic of ADHD from the perspective on international healthcare systems that have unique solutions to identified problems. However, there is a limitation in using Korean research because of the issues with the cultural differences in addressing behavioral problems among children.

Critical Review of the Literature

The aforementioned themes are explored below in separate subcategories. The summary table of the key papers reviewed is presented in Appendix B. These articles include the studies by Munoz-Silva and Lago-Urbano (2017), Sanderud, Murphy and Elklit (2010), Shin and Kim (2010) and Stern et al. (2018).

Genetics and Demographic Characteristics

The topic of genetics is discussed in numerous analysed papers, including key pieces of literature. While this aspect of ADHD development is not the focus of the mentioned above works, it is not neglected, but considered a part of the complex framework of ADHD’s occurrence. For instance, Stern et al. (2018) agree that ADHD is a heritable condition, with the possibility of transference ranging up to more than 60 per cent. Therefore, while genetics are not discussed as a primary cause of the disorder, they are not dismissed. Their effect on children is not debated, and genetics continue to take up a considerable space of the discussion (Fowler et al. 2009). In the study of twins, genetics is a major factor in accounting for ADHD symptoms (Stern et al. 2018). It is found that the difference in scores between twins is minimal, but that the influence of genes is not universal. Conversely, the environment can affect one’s health as strongly as their genetics. Such an assessment is objective due to the collected evidence and the proposed rationale based on the numerical ratio.

Other studies selected for the analysis are not as focused on genetic considerations. The medical view of ADHD explored by Stern et al. (2018) seems to align with other findings. Stergiakouli and Thapar (2010) find that genetic predisposition is a major aspect of ADHD development. Therefore, all studies, as well as psychological treatments, should remember to consider the inheritability of the disorder instead of focusing solely on the environmental factors that can affect a child. Moreover, ethical considerations are to be taken into account in order not to violate the principles of interacting with patients and obtaining the necessary data for analysis. Nikolas and Burt (2010) also highlight the challenging framework of determining which of the factors, genetic or environmental, play a more crucial role in one’s occurrence and severity of ADHD. The hereditary nature of ADHD influences another point in assessing the outcomes of parent-child relations – parents’ mental health.

Parental Mental Health (PMH)

This issue is featured in the study by Shin and Kim (2010) who analyse the effects of maternal depression and overall PMH on children and development of ADHD. The authors find that the mental health of parents has a strong influence on that of their children – parents with mental illnesses can not only have children with similar conditions but also exhibit behaviour that is harmful to the child. Agha et al. (2013), for example, argue that parental ADHD is a factor that can lead to child ADHD becoming more severe, especially if parents do not engage in proper treatment or management practices. Such an assumption is potentially valid; nevertheless, more justification in support of this hypothesis could enhance the credibility of the study.

Here, the line between heritability and environmental factors becomes blurred, as parents experiencing mental health problems act as both bearers of genes and people with their own behavioural patterns and concerns. According to Fleck et al. (2015), families, where both a mother and a child have ADHD, can have interpersonal problems since mothers may perceive the health of their child as a significant factor in familial relations. Fleck et al. (2015) outline that hostility is a crucial aspect in such families and it should be evaluated in addition to other symptoms and signs. Here, one should consider the various impacts that PMH can have on children.

The most significant point one has to make is to show how maternal (and, potentially, paternal) depression can affect children’s view of the world and themselves. According to Shin and Kim (2010), depressive moods and behaviours can be both factors and outcomes of a child’s ADHD. A mother may find that her child has mental health concerns and be impacted by this information. Contrarily, a parent with mental health issues may mistreat a child, leading to the young person developing some symptoms of ADHD. Apart from ADHD and depression, other disorders can also be considered as factors of ADHD occurrence. Sundquist, Sundquist and Ji (2014) provide some examples of alcohol use conditions in family members as causes or aggravators of ADHD development in children. The scholars conclude that mental health problems in parents and other close relatives affect their behaviour, ultimately leading to different parenting techniques and lowered levels of attention toward their children’s wellbeing. This assumption is reasonable because parents who are neglectful may not be able to control the development of their children.

Parenting stress, developed as a response to a child’s ADHD diagnosis, however, does not imply that parents’ mental health will not affect the child’s condition in the future. Theule et al. (2011) discuss that childhood ADHD is a predictor of parents’ stress which can lead to parental ADHD symptomatology and subsequent relationship change. In fact, researchers state that parent’s ADHD symptoms may increase if their child presents a similar behaviour. Therefore, there exists a clear correlation between parents’ and children’s mental wellbeing – children and parents with ADHD or related symptoms depend on each other’s attitude and responses in their recovery and management. The authors underline the need to address these concerns through parent education and symptom assessment for all members.

Comorbidities

Another aspect of ADHD development mentioned briefly in the examined works is the existence of comorbidities in children and the effects of other mental health conditions on ADHD symptoms. Munoz-Silva and Lago-Urbano (2016) investigate the effects of such comorbidities as oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), speech or expression disorders and learning disorders. The authors find that co-existence of these particular conditions and ADHD is high, which may suggest that there is a link between the development processes and the causes of these issues. This observation is valuable because caring for patients presenting co-morbid diagnoses is a common practice among medical personnel. The presence of such disorders strongly influences parents’ behaviour, leading to major changes in their interactions with children (Forssman et al. 2012). For instance, parents may become critical of their children’s abilities, or, in contrast, permit excessive indulgence. Both patterns can result in ADHD development and progression due to inappropriate parenting techniques, note Munoz-Silva and Lago-Urbano (2016). The scholars show how criticism is heightened in parents of children with comorbidities, therefore, increasing the level of rejection in such relationships and contributing to the child’s negative self-perception.

The finding discussed in the key text is supported by other analysed evidence. Flores, Salum and Manfro (2014) examine different comorbidities of children and determine that young people with ADHD and anxiety disorder have problems connecting with their family members. This leads to conflicts of a higher level that is not usually present in families where a child only has ADHD (Flores, Salum and Manfro 2014). However, the studies differ in their opinions on family dynamics related to autonomy and dependency. Flores, Salum and Manfro (2014) argue that people with ADHD and comorbidities do not always live in environments that are characterised by a high level of interdependency and discouraged autonomy. Nonetheless, they show that some previous research considers such conditions a possibility. Such an assessment makes it possible to determine the degree of parents’ responsibility for helping their children and identify the significance of joint rehabilitation activities. Therefore, co-dependency in families with ADH is a topic that continues to require additional research.

Socioeconomic Factors

Another influence on children’s ADHD that comes from a specific environment usually created by parents is linked to various socioeconomic factors. In this case, one can concentrate on financial opportunities of parents, their education levels, living conditions, and similar aspects. The key study that examines the connection between these points is by Rydell (2010) who focuses on education, single and step-parenthood, and demographics of parents. The author determines that negative events such as previous economic hardships or trauma related to relocation and refugee status can substantially contribute to the development of ADHD in children. It should be noted that this study was completed in Sweden, and the author admitted the country’s egalitarian demographics (Rydell 2010). Thus, economic disparity was not a major factor for people who were born in Sweden. As a contrast, the majority of negative experiences were strongly tied to parents’ race and history of relocation, meaning that financial and cultural problems affected their children and had a long-term effect on family health.

The socioeconomic issues of families living in other countries provide a similar connection between challenging environments and mental health. Russell et al. (2014) collect information from the United States, Australia and Northern Europe and compare it to that of the United Kingdom. They conclude that poverty, income, maternal education and housing issues are crucial in affecting children’s mental health. Authors also state that lone parenthood and younger motherhood are linked to higher levels of ADHD (Chang et al. 2014; Russell et al. 2014). Mulligan et al. (2013) note that the presence of siblings without ADHD further complicates interpersonal relations. Therefore, the findings of the key piece of literature can be expanded on, showing a wide range of socioeconomic factors that negatively affect children’s ADHD development.

Some other articles also consider family income and poverty in relation to ADHD occurrence. Larsson et al. (2014) study a number of Swedish families and find a strong link between low income and ADHD. Nevertheless, the researchers comment that their findings cannot establish causality, rather only show that the link exists between the two concepts. Nigg and Craver (2014) offer a response to the previous studies, reflecting on the connection between finances and ADHD. They highlight that it may be challenging for the scientific world to agree with the fact that socioeconomic struggles are a factor in ADHD development. The research outcomes indicate that disadvantages brought by financial hardships are expansive – people without money cannot access proper medical care, nutrition, housing and education. As a result, they can also experience higher levels of stress which, in turn, impacts familial relationships and leads to conflicts with children. Neglect is another major concern, as children of parents who are stressed, malnourished and consumed with work may develop negative behavioural patterns as a response to the lack of proper attention.

Negative Life Events

The factor described above is closely related to the next point that is considered in some capacity in all analysed research studies. Children who live in environments affected by parents’ stress, mental health problems, socioeconomic disadvantages, and adverse behaviours become traumatised by such conditions (de Oliveira Pires, da Silva and de Assis 2013). As an outcome, their risk for developing ADHD may increase, especially if they already have a genetic predisposition to this disorder. Negative life events can range from the ones listed above to physical, emotional and sexual abuse. There is link between such events and ADHD development and it is stated that the exposure of children to such events is connected to their mental health concerns. Study findings show that many factors can contribute to the development of symptoms, the most impactful life event being socioeconomic hardship described above.

However, there exist other factors, some of which were briefly mentioned previously. Divorce, for instance, is a major change in a child’s life – it is often followed by a shift in family dynamics and is connected to sadness and loss in the mind of a child. Substance abuse and mental illness are also contributors to ADHD development as research shows. Another potential factor is neighbourhood violence – a concept not mentioned in other studies with similar concerns. It is implied that a child’s perception of the word can change after seeing or being exposed to some portrayal of violence. Next, a relative serving a custodial sentence in prison is brought up as a possible adverse event. Results for domestic violence are apparent in showing the discrepancy between people with ADHD having a high level of exposure to it and people without ADHD having a low prevalence (de Oliveira Pires et al., 2013).

Other factors such as discrimination based on some personal characteristic and death of a loved one are among the less impactful but present events. As a result, a variety of negative situations can lead to a child developing ADHD. Thus, one cannot rely on the assessment of genetics or comorbidities alone. The authors highlight the necessity to address all parts of patients’ lives in order to deliver care and determine the best treatment approach. Moreover, the scholars insist that the failure to identify such factors can negatively affect one’s management of the disorder and prevent patients from reaching an understanding of their behaviours and thoughts.

These conclusions are supported by other researchers who emphasise the impact of the findings on clinical practice. Abuse is highlighted in many works as a prominent contributor to ADHD. Sanderud, Murphy and Elklit (2016) research different types of abuse (physical, emotional, sexual) to determine their connection with ADHD development. They find that general abuse is strongly related to the diagnosis of ADHD, although emotional and sexual violence is also recurrent in the examined data. The sample of the study focused on young adults, but the abusive events were not confined to recent times. As a result, the research can be considered as a foundation for developing new recommendations for ADHD therapy.

Other studies mention abuse and supports these findings as well. Singer, Humphreys and Lee (2016) examine responses of people with ADHD to trauma and determine that coping strategies mitigate the effect of ADHD in adulthood. Cook et al. (2017) and Littman (2009) argue that the effect of trauma in children is complex – people with ADHD, depending on their response to abuse, can maintain the symptoms in adulthood or surpass them with time. Conway, Oster and Szymanski (2011) further reinforce the link since they find a correlation between repeated instances of abuse and other negative events and children’s ADHD. The authors emphasise the need to address the notion of mentalisation – the realisation of one’s actions as meaningful (Conway, Oster and Szymanski 2011). In this case, the engagement of specialists working in the field of mental health is of great importance because, as Littman (2009) remarks, professional involvement contributes to fastening the recovery process. Spinazzola et al. (2017) highlight the effect of trauma on children and reinforce the conclusions stated above. Overall, the impact that abuse, socioeconomic disparities, and other negative life events have on children cannot be overlooked in diagnosing and treating ADHD.

Chosen Area for Service Improvement

The review of presented above studies shows how complicated the intervention for treating ADHD can be. While many processes when dealing with patients with ADHD involve correct medication and doses, non-pharmacological methods should not be ignored (Young and Myanthi Amarasinghe 2010). Therefore, it is vital to examine aspects in creating a treatment plan and providing services for people with ADHD. The common themes expressed in all examine studies show that the complex nature of ADHD development often includes the influence of parents and the environment on children at risk of developing the condition. Hence, many research articles review parent education and family therapy as crucial methods of dealing with the diagnosis and managing symptoms without medication. Moreover, these options are considered to provide children or adults with ADHD with holistic care that will benefit intrapersonal relationships, address the underlying problems, and have a long-lasting effect on one’s mental wellbeing.

While there many types of therapies for treating ADHD exist, a number of them are reviewed as opportunities for change. For instance, Van der Oord, Bögels and Peijnenburg (2012) promote mindfulness for both parents as their children with ADHD as a practice that allows for self-reflection and understanding of positive and negative behaviours, as well as their outcomes. In parallel, the participation of mental health nurses is essential since control over this training is essential due to an opportunity to make the necessary adjustments timely. The area for improvement that is suggested in many sources is parental education to prevent, mitigate and manage the effects of negative life events on children at risk or with ADHD. The diagnosing process and the assessment of children with challenging situations are not always timely. Thus, young patients may be already experiencing ADHD symptoms influenced by past adverse situations. In order to minimise further harm, one can look into ways of improving educational opportunities for patients and caregivers. Such a plan can lead to better parent-child relations and allow young adults to lead a fulfilling life without ADHD-related complications.

It is clear that some of the factors mentioned above cannot be fully resolved with the help of service improvement. Socioeconomic factors, for example, are a challenging problem that is based on governmental, local, and personal systems of one’s environment. Nonetheless, one can help families in maintaining a level of emotional connection with children, adolescents, and young adults who have ADHD. Similar to other presented works, Moghaddam et al. (2013) show that parenting styles of people whose children have ADHD differ from those of individuals with children without mental health issues. This idea should be explored in a parent education practice that offers parenting activities which focus on intrapersonal communication, emotional balance, and positive reinforcement.

Plan to Implement Service Improvement

Identified Area and Change

While many of the discussed issues cannot be addressed by mental health nurses, one particular problem may become a part of patient and caregiver education. The relationship between parents and children is a connection that can significantly impact children’s health in both a positive and negative way. One can see that parents’ neglectful or authoritative behaviour leads to children’s ADHD increased severity and its persistence into adulthood (Schroeder and Kelley 2009). In a less recent study, Crittenden and Kulbotton (2007) propose a link between a mother’ distress and a child’s ADHD symptoms, stating that the lack of control and focus of the parent may lead to an overall stressful family relationship. Therefore, one may conclude that parent education is a vital service opportunity for ADHD treatment.

In this case, nurses should focus on developing a program that will educate parents of children with or at risk of ADHD how to treat their child and address any arising concerns. Here, service improvement is necessary since many parents still do not have enough knowledge about dealing with ADHD. As Sayal et al. (2015) find, the majority of parents simply do not possess information about the ways in which they can help their children. Family members do not know which specialists can offer help and what methods should the family use to avoid conflicts. Currently, the result of parent training is not ubiquitously positive, with studies revealing different success rates for such interventions (Zwi et al. 2011). Thus, the focus on service improvement in this area is essential to deliver better care.

As a potentially effective change practice, the PDSA (plan-do-check-act) mode may be applied. According to Christoff (2018), such an intervention utilised by mental health medical personnel is relevant to helping patients with ADHD due to step-wise sound activities. The main target of the parent education programmes would be to lower the impact of past adverse situations and avoid the occurrence of new negative life events. Therefore, the focus on compassion, positive reinforcement and empowerment is crucial for the programme to become effective (Barkley 2011). The involvement of medical professionals working in the field of mental health is a mandatory practice. Emotions play a major role in managing ADHD since the disorder is directly connected with one’s response to negative events. Parents should learn how to influence their children’s’ worldview which is often affected by traumatic experiences and socioeconomic factors (Barkley 2011). While some of these cannot be fixed, their interpretation (mentalisation) can be improved.

Therefore, the intervention centred on improving people’s access to and understanding of parent education may benefit people with ADHD and their relatives. Such training plans already focus on parenting skills, providing families with knowledge about authority, participation, kindness, and strictness as parenting techniques. However, one can also include some evaluation techniques to address parents’ stress and potential mental health concerns. Parents with ADHD, depression or anxiety symptoms may not understand their own needs and increase tensions in the family. Moreover, it is shown that parents often experience stress due to children’s ADHD which further exacerbates conflicts and limits positive parent-child interactions (Moen, Hedelin and Hall-Lord 2015). As a result, the withdrawal of a parent from such relations significantly worsens a child’s condition and leads to ADHD becoming severe.

Here, the main improvement technique is to increase therapists’ skills and create programmes that offer families a non-judgemental and empowering system where they can find comfort and build trusting relations with each other. Mental health nurses can educate parents about the advantages of talking to their children and paying attention to their activities and interests. On the other hand, some parts of learning should focus on preventing excessive indulgence in order to prevent parents from enabling their child’s negative behaviour. Tancred and Greeff (2015) state that authoritative traits such as autonomy granting, regulation, and connection are beneficial for families with ADHD, arguing that parents and caretakers should be taught these strategies to help their children. The balance between these practices has to become the centre of all teaching activities – parents should understand that ADHD is not an untreatable condition but see that their child’s mental health is a vital part of their life.

For this reason, some parents may benefit from learning in groups, while others may prefer one-on-one interactions with a nurse and, on some occasions, their child. Group-based programmes are effective in giving parents an opportunity to share their grievances with individuals who have similar experiences (Koerting et al. 2013). As a contrast, single-visitor options are more flexible and allow a nurse to establish a connection with parents who could ask more personal questions and address their individual problems.

Barriers to Implementation

There exist many barriers that prevent people from accessing or seeking medical services. Smith et al. (2015) suggest that the most basic reason is lack of awareness about such services. Other issues that arise in such programmes are the low motivation of parents to participate in such opportunities, stigma or psychological support, as well as limitations in time, money and transportation (Gwernan-Jones et al. 2015). To address these barriers and monitor the effectiveness of the new structure, a mental health nurse can collaborate with other service members and introduce a number of changes. First of all, the overall awareness of the services should be increased. This can be achieved with the help of community services that work with underrepresented groups of people (Koerting et al. 2013). Minority groups, single parents, fathers, underserved populations and other communities may be reached through word of mouth – although it is not an official way of delivering information, it is perceived by many people as trustworthy and legitimate (Gwernan-Jones et al. 2015). The PDSA practice requires the participation of all interested persons, including not only patients but also parents. Therefore, in order to eliminate possible mistakes, preliminarily, it is essential to explain all the stakeholders the importance of working coherently.

The next potential barrier is the lack of motivation for parents to participate in the PDSA programme. This problem may be connected to a variety of others; parents may not believe in the services’ effectiveness or not care about changing their parenting practices. Şipoş et al. (2012) find that parents in families with ADHD children do not consider family relations as a factor that influences their and their children quality of life. The evidence, however, shows that children in such conditions report being less happy, satisfied with themselves, or confident in their health. Clarke et al. (2015) show that parent attendance and participation in their child’s life is vital in helping them overcome and manage ADHD. This parent behaviour is a significant limitation to service use, and it cannot be overcome through simple means. Some suggestions include a system of rewards for parents who complete the training and demonstrate change as well as positive reinforcement to show the parents the effects that their change in behaviour can bring. For these measures to work, nurses should pay significant attention to programmes flexibility.

Here, another barrier arises – parent education implies that caregivers should allocate time to train and visit medical facilities. To overcome this issue, nurses can tailor the PDSA programme to adhere to parents’ specific needs. For example, if parents need additional sessions to explore their mental health and stress in relation to their child’s ADHD, nurses should connect them with necessary specialists or provide information in the form of publications and media (Koerting et al. 2013). Similar to the issue of stigma and openness, group therapy may not work for some but be very effective for other parents. Group sessions are less flexible in their time frame, but they give parents an opportunity to exchange knowledge without nurse’s intervention (Koerting et al. 2013). As a result, one can see that both options should be made readily available for parents to ensure the highest level of participation.

Evaluation

The evaluation of the project is vital to its success since it can help nurses and other healthcare specialists to see the strengths and limitations of the initiative. According to Brewster et al. (2015), teamwork and planning should be inherent to the process in order to yield usable and reliable results. They offer a concordat system that outlines goals for participating researchers as well as responsibilities for evaluators, supporting members, and participators. Here, the responsibility of nurses would be to implement new guidelines for parent education and increase parents’ interest in therapy. For families, the main responsibility would be to deliver trustful information. Then, strategies for data collection should be agreed upon to minimise the burden on one members of the team. Brewster et al. (2015) note the importance of addressing the ethical issues of this assessment and ensuring that all participants’ data is confidential.

The improvement of parent training can be evaluated by collecting data about families’ quality of life (QoL) indicators. In their study, Şipoş et al. (2012) use QoL numbers to analyse the environments of families where children have ADHD or autism spectrum disorders. They are able to record data about parents and children’s perception of familial ties, interpersonal communication, support, hostility, openness and other similar indicators. A similar approach can benefit this study as well since it is focused on providing parents with more information about their parenting style. The information can be collected from involved practices, and parents may participate in studies to determine their level of involvement in their children’s life. As an outcome, one may determine whether the change of the service was effective. The intervention can be implemented in a span of six months, during which both clinicians and parents will gain an opportunity to revise their knowledge and apply new skills. This time frame is long enough to collect data at different points of time but also rather short, which may encourage health providers to act effectively.

Reflection on Key Personal Learning

This research project provides insight into the treatment and management practices of ADHD that are concerned not only with service users’ own thoughts but also their perception of the world and their environment. It is clear that parents play a significant role in their children’s lives. However, the extent of this impact is sometimes not acknowledged enough to contribute to mental health nursing practices. The review of key literature shows how vital this consideration may be. Parents of children with or at risk of ADHD can and should be consulted and taught about their child’s health. The present study also reveals how some adverse life events cannot be controlled, thus making ADHD treatment a challenging venture. Socioeconomic factors and past cases of abuse may affect people and lead to long-lasting complications. Nonetheless, the addressed area of parent education aims to prevent further harm and minimise the impact that past negative events may have on the child.

Reference List

Agha, S.S., Zammit, S., Thapar, A. and Langley, K. (2013) Are parental ADHD problems associated with a more severe clinical presentation and greater family adversity in children with ADHD? European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 22(6), pp. 369-377.

Barkley, R.A. (2011) The importance of emotion in ADHD. Journal of ADHD and Related Disorders. 1(2), pp. 5-37.

Bornovalova, M. A., Blazei, R., Malone, S. H., McGue, M. and Iacono, W. G. (2013) Disentangling the relative contribution of parental antisociality and family discord to child disruptive disorders. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 4(3), pp. 239-246.

Brewster, L., Aveling, E.L., Martin, G., Tarrant, C., Dixon-Woods, M., Safer Clinical Systems Phase 2 Core Group Collaboration and Writing Committee (2015) What to expect when you’re evaluating healthcare improvement: a concordat approach to managing collaboration and uncomfortable realities. BMJ Quality and Safety. 24(5), pp. 318-324.

Chang, Z., Lichtenstein, P., D’Onofrio, B.M., Almqvist, C., Kuja-Halkola, R., Sjölander, A. and Larsson, H. (2014) Maternal age at childbirth and risk for ADHD in offspring: a population-based cohort study. International Journal of Epidemiology. 43(6), pp. 1815-1824.

Christoff, P. (2018) Running PDSA cycles. Current problems in pediatric and adolescent health care. 48(8), pp. 198-201.

Clarke, A.T., Marshall, S.A., Mautone, J.A., Soffer, S.L., Jones, H.A., Costigan, T.E., Patterson, A., Jawad, A.F. and Power, T.J. (2015) Parent attendance and homework adherence predict response to a family–school intervention for children with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 44(1), pp. 58-67.

Conway, F., Oster, M. and Szymanski, K. (2011) ADHD and complex trauma: a descriptive study of hospitalized children in an urban psychiatric hospital. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy. 10(1), pp. 60-72.

Cook, A. et al. (2017) Complex trauma in children and adolescents. Psychiatric Annals. 35(5), pp. 390-398.

Cooper, C., Booth, A., Varley-Campbell, J., Britten, N. and Garside, R. (2018) Defining the process to literature searching in systematic reviews: A literature review of guidance and supporting studies. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 18, pp. 85-95.

Crittenden, P. M. and Kulbotton, G. R. (2007) Familial contributions to ADHD: an attachment perspective. Tidsskrift for Norsk Psykologorening. 10, pp. 1220-1229.

de Oliveira Pires, T., da Silva, C.M.F.P. and de Assis, S.G. (2013) Association between family environment and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children–mothers’ and teachers’ views. BMC Psychiatry. 13(1), p. 215.

Fleck, K. et al. (2015) Child impact on family functioning: a multivariate analysis in multiplex families with children and mothers both affected by attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders. 7(3), pp. 211-223.

Flores, S.M., Salum, G.A. and Manfro, G.G. (2014). Dysfunctional family environments and childhood psychopathology: the role of psychiatric comorbidity. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. 36(3), pp. 147-151.

Forssman, L., Eninger, L., Tillman, C. M., Rodriguez, A. and Bohlin, G. (2012) Cognitive functioning and family risk factors in relation to symptom behaviors of ADHD and ODD in adolescents. Journal of Attention Disorders. 16(4), pp. 284-294.

Fowler, T., Langley, K., Rice, F., van den Bree, M.B., Ross, K., Wilkinson, L.S., Owen, M.J., O’donovan, M.C. and Thapar, A. (2009) Psychopathy trait scores in adolescents with childhood ADHD: the contribution of genotypes affecting MAOA, 5HTT and COMT activity. Psychiatric Genetics. 19(6), pp. 312-319.

Ghosh, M., Fisher, C., Preen, D. B. and Holman, C. A. J. (2016) “It has to be fixed”: a qualitative inquiry into perceived ADHD behaviour among affected individuals and parents in Western Australia. BMC Health Services Research. 16(141), pp. 1-12.

Grabermann, M., Zimmermann, M., Strunz, L., Ebbert-Grabemann, M., Scherbaum, N., Kis, B. and Mette, C. (2017) New ways of diagnosing ADHD in adults. Psychiatrische Praxis. 44(4), 221-227.

Grewal, A., Kataria, H. and Dhawan, I. (2016) Literature search for research planning and identification of research problem. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia. 60(9), pp. 635-639.

Gwernan-Jones, R., Moore, D.A., Garside, R., Richardson, M., Thompson‐Coon, J., Rogers, M., Cooper, P., Stein, K. and Ford, T. (2015) ADHD, parent perspectives and parent–teacher relationships: grounds for conflict. British Journal of Special Education. 42(3), pp. 279-300.

Koerting, J., Smith, E., Knowles, M.M., Latter, S., Elsey, H., McCann, D.C., Thompson, M. and Sonuga-Barke, E.J. (2013) Barriers to, and facilitators of, parenting programmes for childhood behaviour problems: a qualitative synthesis of studies of parents’ and professionals’ perceptions. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 22(11), pp. 653-670.

Larsson, H., Sariaslan, A., Långström, N., D’onofrio, B. and Lichtenstein, P. (2014) Family income in early childhood and subsequent attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a quasi-experimental study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 55(5), pp. 428-435.

Littman, E.B. (2009) Toward an understanding of the ADHD-trauma connection. Sexual Abuse. 20, pp. 359-378.

Moen, Ø. L., Hedelin, B. and Hall-Lord, M. L. (2015) Parental perception of family functioning in everyday life with a child with ADHD. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 43(1), pp. 10-17.

Moghaddam, M.F., Assareh, M., Heidaripoor, A., Rad, R.E. and Pishjoo, M. (2013) The study comparing parenting styles of children with ADHD and normal children. Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. 15(4), pp. 45-49.

Mulligan, A., Anney, R., Butler, L., O’Regan, M., Richardson, T., Tulewicz, E.M., Fitzgerald, M. and Gill, M. (2013) Home environment: association with hyperactivity/impulsivity in children with ADHD and their non‐ADHD siblings. Child: Care, Health and Development. 39(2), pp. 202-212.

Munoz-Silva, A. and Lago-Urbano, R. (2017) Child ADHD severity, behavior problems and parenting styles. Annals of Psychiatry and Mental Health. 4(3), p. 1066.

Nigg, J.T. and Craver, L. (2014) Commentary: ADHD and social disadvantage: an inconvenient truth? – a reflection on Russell et al. (2014) and Larsson et al. (2014). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 55(5), pp. 446-447.

Nikolas, M.A. and Burt, S.A. (2010) Genetic and environmental influences on ADHD symptom dimensions of inattention and hyperactivity: a meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 119(1), pp. 1-17.

Robin, A.L. (2014) Family therapy for adolescents with ADHD. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics. 23(4), pp. 747-756.

Rodgers, B.L. (2011) Literature review critique tool. Web.

Russell, G., Ford, T., Rosenberg, R. and Kelly, S. (2014) The association of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with socioeconomic disadvantage: alternative explanations and evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 55(5), pp. 436-445.

Sanderud, K., Murphy, S. and Elklit, A. (2016) Child maltreatment and ADHD symptoms in a sample of young adults. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 7(1), p. 32061.

Sayal, K., Mills, J., White, K., Merrell, C. and Tymms, P. (2015) Predictors of and barriers to service use for children at risk of ADHD: longitudinal study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 24(5), pp. 545-552.

Schroeder, V. M. and Kelley, M. L. (2009) Associations between family environment, parenting practices, and executive functioning of children with and without ADHD. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 18(2), pp. 227-235.

Shin, H.S. and Kim, J.M. (2010) Analysis of relationships between parenting stress, maternal depression, and behavioral problems in children at risk for attention deficit hyperactive disorder. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing. 40(3), pp. 453-461.

Singer, M. J., Humphreys, K. L. and Lee, S. S. (2016) Coping self-efficacy mediates the association between child abuse and ADHD in adulthood. Journal of Attention Disorders. 20(8), pp. 695-703.

Şipoş, R., Predescu, E., Mureşan, G. and Iftene, F. (2012) The evaluation of family quality of life of children with autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit hyperactive disorder. Applied Medical Informatics. 30(1), pp. 1-8.

Smith, E., Koerting, J., Latter, S., Knowles, M.M., McCann, D.C., Thompson, M. and Sonuga-Barke, E.J. (2015) Overcoming barriers to effective early parenting interventions for attention‐deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): parent and practitioner views. Child: Care, Health and Development. 41(1), pp. 93-102.

Spinazzola, J., Ford, J.D., Zucker, M., van der Kolk, B.A., Silva, S., Smith, S.F. and Blaustein, M. (2017) Survey evaluates: complex trauma exposure, outcome, and intervention among children and adolescents. Psychiatric Annals. 35(5), pp. 433-439.

Stergiakouli, E. and Thapar, A. (2010). Fitting the pieces together: current research on the genetic basis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 6, pp. 551-560.

Stern, A., Agnew-Blais, J., Danese, A., Fisher, H.L., Jaffee, S.R., Matthews, T., Polanczyk, G.V. and Arseneault, L. (2018) Associations between abuse/neglect and ADHD from childhood to young adulthood: a prospective nationally-representative twin study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 81, pp. 274-285.

Sundquist, J., Sundquist, K. and Ji, J. (2014) Autism and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among individuals with a family history of alcohol use disorders. Elife. 3, p. e02917.

Tancred, E.M. and Greeff, A.P. (2015) Mothers’ parenting styles and the association with family coping strategies and family adaptation in families of children with ADHD. Clinical Social Work Journal. 43(4), pp. 442-451.

Tarver, J., Daley, D. and Sayal, K. (2014) Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): an updated review of the essential facts. Child: Care, Health and Development. 40(6), pp. 762-774.

Thapar, A., Cooper, M., Eyre, O. and Langley, K. (2013). Practitioner review: what have we learnt about the causes of ADHD? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 54(1), pp. 3-16.

Thapar, A., Cooper, M., Jefferies, R. and Stergiakouli, E. (2012) What causes attention deficit hyperactivity disorder? Archives of Disease in Childhood. 97(3), pp. 260-265.

Theule, J., Wiener, J., Rogers, M.A. and Marton, I. (2011) Predicting parenting stress in families of children with ADHD: parent and contextual factors. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 20(5), pp. 640-647.

Uchida, M., Spencer, T.J., Faraone, S.V. and Biederman, J. (2018) Adult outcome of ADHD: an overview of results from the MGH longitudinal family studies of pediatrically and psychiatrically referred youth with and without ADHD of both sexes. Journal of Attention Disorders. 22(6), pp. 523-534.

Van der Oord, S., Bögels, S.M. and Peijnenburg, D. (2012) The effectiveness of mindfulness training for children with ADHD and mindful parenting for their parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 21(1), pp. 139-147.

Young, S. and Myanthi Amarasinghe, J. (2010) Practitioner review: non-pharmacological treatments for ADHD: a lifespan approach. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 51(2), pp. 116-133.

Yousefia, S., Far, A.S. and Abdolahian, E. (2011) Parenting stress and parenting styles in mothers of ADHD with mothers of normal children. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 30, pp. 1666-1671.

Zwi, M., Jones, H., Thorgaard, C., York, A. and Dennis, J.A. (2011) Parent training interventions for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in children aged 5 to 18 years. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (12), pp. 1-100.

Appendix A: Flow Diagram