Introduction

Theories present structured views of distinct aspects of the nursing profession.

A nursing theory can guide practice, establish a basis for policies, and be involved in research (Mintz-Binder, 2019).

Middle-range nursing theories offer clinically specific approaches to interacting with patients and colleagues, and Madeleine Leininger’s Culture Care theory (CCT) suggests unique ideas concerning a nurse’s work (Mintz-Binder, 2019).

Consequently, the objectives of this presentation are to identify Leininger’s assumptions and demonstrate a detailed example of how her theory can be used in practice.

The Theorist

Culture Care Theory

Leininger has put an immersive effort into Culture Care theory.

After Madeleine Leininger had worked with a tribal group in Papua New Guinea, she introduced the theory’s conceptualizations in her dissertation and explicated the findings in a later journal article (McFarland & Wehbe-Alamah, 2019).

The theorist argued that the concept of care lacked diverse cultural viewpoints, requiring a different approach, and indicated the need to discover people’s perceptions of care from a holistic approach (McFarland & Wehbe-Alamah, 2019).

Therefore, Leininger’s CCT, which is also known as the Cultural Care Diversity and Universality theory, aimed to help practitioners understand the connections between care and the differences and similarities of distinct cultures (McFarland & Wehbe-Alamah, 2019).

Leininger was the founder of a new perceptive on providing care concerning patients’ cultural backgrounds.

Guides nurses toward culturally congruent care

Cultural Care theory presents benefits for patients and healthcare professionals.

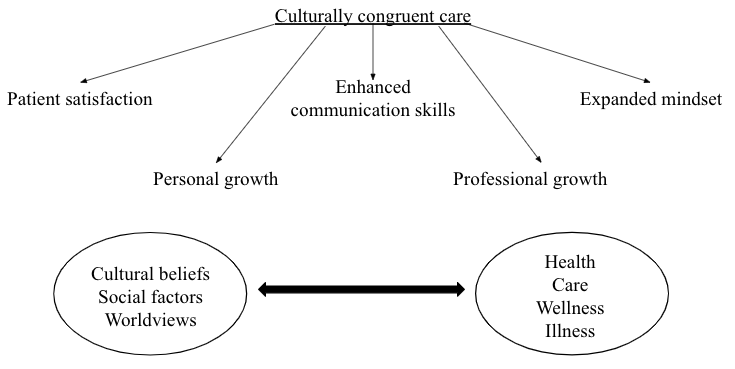

CCT was designed to guide nurses through the process of exploring specific meanings, expressions, and practices toward culturally congruent care (McFarland & Wehbe-Alamah, 2019).

Such care is perceived to be essential for patient satisfaction, with positive cultural experiences resulting in enhanced communication skills, expanded mindsets, and personal and professional growth (Alexander-Ruff & Kinion, 2018).

CCT suggests that nurses should not separate cultural beliefs, social factors, and worldviews from health, care, wellness, or illness (McFarland & Wehbe-Alamah, 2019).

In particular, healthcare providers need to assess cultural practices, religion, family and kinship, technology, education, politics, and economics when making decisions regarding each patient’s needs (McFarland & Wehbe-Alamah, 2019).

As nurses obtain knowledge of peoples’ prior experiences, all parties become more involved in the treatment process, leading to better patient outcomes.

The Theory

Diversity and universality play significant roles in Cultural Care theory.

The concept of diversity refers to each individual’s distinctions concerning values, meanings, symbols, and other characteristics regarding specific preferences of patients from varying cultures (McFarland & Wehbe-Alamah, 2019).

For instance, a study of Somali immigrant refugees in Minnesota has indicated the importance of gender-based differences in care (McFarland & Wehbe-Alamah, 2019).

On the other hand, universality involves similar or commonly shared cultural phenomena that can navigate healthcare professionals toward assistive and supportive care (McFarland & Wehbe-Alamah, 2019).

For example, research on parenting African-American children with autism has determined two universal care themes: faith and respect (McFarland & Wehbe-Alamah, 2019).

While diversity within CCT identifies the uniqueness of each culture, universality suggests resemblances that can be helpful in providing care.

Assumptions

Nurses can use the Cultural Care theory’s assumptions when working with different cultural groups.

The first assumption recognizes care as an essential, distinct, and unifying focus of nursing (McFarland & Wehbe-Alamah, 2019).

Subsequently, care must be scientific and humanistic to lead the path toward facing disabilities and death and achieving health, well-being, and growth (McFarland & Wehbe-Alamah, 2019).

Moreover, caring is vital for curing, for if nobody provides care for people, they will not be healed (McFarland & Wehbe-Alamah, 2019).

CCT assumes the cruciality of appropriate care in securing sufficient patient outcomes.

Furthermore, the theory makes several assumptions regarding the specifics of cultural care.

Firstly, the synthesis of culture and care navigate the researcher toward exploring, understanding, and accounting for well-being and health (McFarland & Wehbe-Alamah, 2019).

Secondly, expressions, patterns, meanings, and processes of cultural care are diverse, but all cultures have some shared universalities (McFarland & Wehbe-Alamah, 2019).

Thirdly, beliefs, values, and practices of cultural care are influenced by and ingrained in ethnohistorical and environmental contexts, worldviews, and social factors, including but not limited to religion, kinship, and economics (McFarland & Wehbe-Alamah, 2019).

Cultural care is affected by multiple aspects of life but has the power to direct practice.

Finally, the theory’s assumptions concentrate on culturally congruent care and transcultural nursing.

The first one suggests that culturally congruent care practices depend on generic and professional care (McFarland & Wehbe-Alamah, 2019).

The former refers to mainly emic, lay, folk, and naturalistic, while the latter implies a more etic approach (McFarland & Wehbe-Alamah, 2019).

Moreover, caregivers should fully comprehend beliefs, values, and patterns and use them appropriately and meaningfully to ensure culturally congruent and therapeutic care (McFarland & Wehbe-Alamah, 2019).

Lastly, transcultural nursing can be defined as a discipline consisting of theoretical and practical knowledge that assists healthcare professionals in learning and providing culturally congruent care (McFarland & Wehbe-Alamah, 2019).

Overall, the assumptions of CCT reflect the significance of considering patients’ diverse preferences when making decisions regarding the treatment process.

Personal Practice

I have been using some aspects of this theory in my personal practice for quite some time.

I work on the gastrointestinal (GI) floor at my hospital and typically interact with medical-surgical patients from various backgrounds.

The patients have diverse disorders occurring within their gastrointestinal tracts and react differently to their diagnoses.

In addition to prior medical history, those reactions are often affected by patients’ spiritual and religious beliefs, socioeconomic status, and the presence of loved ones.

As a result, some respond calmly to treatment, surgeries, and recovery processes, while others act reluctantly or panic.

Consequently, I strive to learn more about the causes of patients’ concerns and their preferences, transmitting the information further to my colleagues to prevent errors and ensure that patients will feel as comfortable as possible.

For instance, I use the theory’s assumption that all cultures are diverse but share universalities (McFarland & Wehbe-Alamah, 2019).

In particular, if a patient exhibits resistance, I ask about their expectations and what I can do to help them.

Typically, the patient would become more open and describe their worries, presenting ways to reach an agreement and make relevant decisions.

Patients and doctors rely on me, a nurse, to communicate important information with respect to patient needs and values, and I understand the essence of my profession in providing appropriate and meaningful care.

Example of Usage

Furthermore, Leininger’s theory was used in practice by several researchers.

For example, Zahra Rahemi (2019) applied CCT in practical settings to explore connections between attitudes toward planning for EOL (end-of-life) care and such factors as spirituality and social support.

Rahemi (2019) argued that older adults with diverse ethical and cultural backgrounds represent one of the fastest-growing populations in the US, indicating the existence of issues related to culturally-competent EOL care.

Such older adults as Iranian Americans are less likely to seek and receive hospice and palliative care or obtain EOL care knowledge compared to their non-Hispanic White peers (Rahemi, 2019).

Due to prior studies on senior adults with diverse ethical and cultural backgrounds emphasizing the importance of cultural factors, Rahemi (2019) utilized Cultural Care Diversity and Universality theory as the framework for his research.

The example suggests that CCT can be used in practice when working with more senior populations.

The results of the study can be employed in further research and serve as guidance on how to interact with CED older adults during EOL care.

Specifically, the research focused on Iranian Americans and cultural factors affecting their perception of care (Rahemi, 1029).

Senior Iranians in the US often struggle with language proficiency which is a predictor of underutilization of health services (Rahemi, 2019).

Moreover, the study implied that a higher level of spirituality was associated with a decreased level of favorable attitudes toward planning EOL care (Rahemi, 2019).

The Iranian population expressed distrust in Western medicine but prioritized the value of trusting relationships with caregivers over the professionals’ technical skills (Rahemi, 2019).

The research advised healthcare providers to restrain their etic perspectives and biases while valuing patients’ emic views (Rahemi, 2019).

People’s cultural backgrounds can present barriers to providing and receiving care, but it is crucial to concentrate on healing and patients’ preferences.

Conclusion

To summarize, Leininger’s Cultural Care Diversity and Universality theory presents a holistic approach to considering patients’ cultural experiences in relation to medical services.

CCT guides practitioners toward culturally congruent care that can benefit both receivers and providers of care.

The theory lists multiple factors which can influence the treatment process and makes several assumptions, including recognizing care as the focus of nursing, valuing cultures’ distinctions and universalities, and reviewing generic and professional care.

CCT was recently used in a study as the framework in practical settings concerning end-of-life care.

The study suggests that despite patients’ attitudes being impacted by their cultures, healthcare professionals can and must build trusting relationships to ensure positive patient outcomes.

References

Alexander-Ruff, J. H., & Kinion, E. (2018). Engaging nursing students in a rural Native American community to facilitate cultural consciousness. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 35(4), 196-206. Web.

McFarland, M. R., & Wehbe-Alamah, H. B. (2019). Leininger’s theory of culture care diversity and universality: An overview with a historical retrospective and a view toward the future. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 30(6), 540-557. Web.

Mintz-Binder, R. (2019). The connection between nursing theory and practice. Nursing Made Incredibly Easy, 17(1), 6-9.

Rahemi, Z. (2019). Planning ahead for end-of-life healthcare among Iranian-American older adults: attitudes and communication of healthcare wishes. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 34(2), 187-199. Web.