Introduction

Polypharmacy is a major problem that can affect anybody, but it is the most common to the elderly population. The concept of polypharmacy encloses the use of five or more medications at the same time (Fick et al., 2003), prescription of more medications than required, and prescription of medications that are inappropriate. Effects of polypharmacy include overmedication, drug interactions that may cause over-or under-dosing, and possibly a lethal outcome. Polypharmacy is prevalent among the elderly population due to higher manifestation of chronic diseases that rely upon various medications, as well as reduced level of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic functioning within this age group (Routledge et al. 2004).

Another factor that explains the higher prevalence of polypharmacy among the elderly is a high prevalence of polyorgan pathology, meaning high individual morbidity levels of two or more chronic illnesses within one single patient. Such patients require separate treatments for each chronic condition, which magnifies their amount of medication intake and enhances the risk of adverse drug reactions. This article identifies and addresses the issue of excessive drug use in order to make primary care doctors (PCDs) aware of the existing problem. This is done for the purpose of enabling PCDs to effectively assess their patient’s drug use patterns and master the skills required to prevent multiple drug use so that polypharmacy in the elderly could be maximally avoided.

Materials and Methods

The quantitative procedures of the current literature review helped to address the challenges that were introduced by multiple answers to the current question of polypharmacy prevention. Results of multiple polypharmacy-focused studies were compared and relevantly combined in order to make accurate estimations of descriptive statistics. The conducted literature review allowed us to arrive at a credible conclusion that addressed an appropriate audience of primary care physicians.

Incidence

It is a known fact that over-the-counter medications are most commonly used by individuals over the age of 65. Various studies have demonstrated that 90% of the elderly population (over 65 years of age) take at least one medication per day, whereas those residing in nursing homes or assisted living facilities to take from six to eight different types of drugs each day (Prybys et al., 2002; Vestal, 1997). According to some estimations people over the age of 60 make up 16% of the U.S. population and consume 40% of all prescription medications (Hogstel, 1992). It has been noted that 90% of elderly individuals take five prescription medications and three over-the-counter medications daily (Darnell et al., 1986), and DeMaagd (1995) mentioned that all elderly individuals take at least two nonprescription drugs. These rates of incidence indicate the acuity of the discussed issue and the need for relevant measures required to solve this problem.

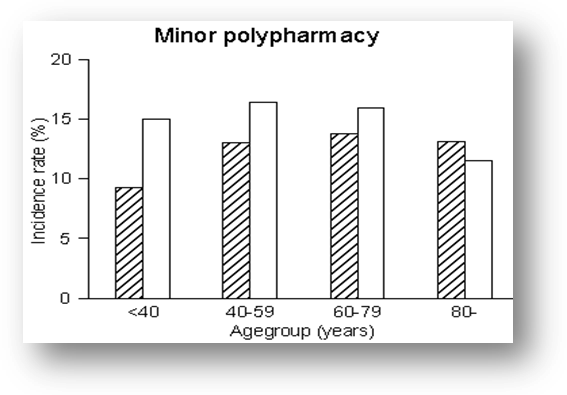

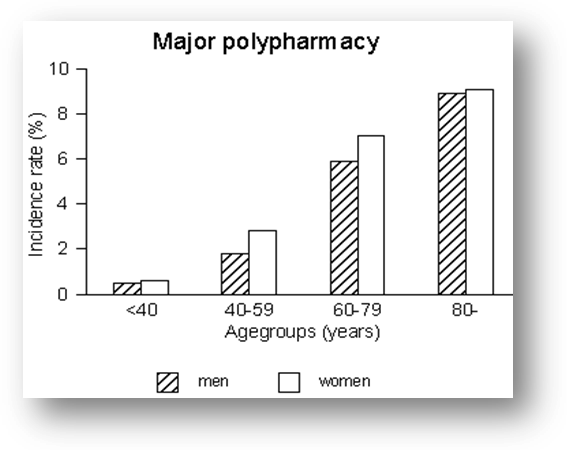

Certain studies have identified the problem of multiple drug use as being divided into two subgroups: minor polypharmacy and major polypharmacy (Bjerrum 1998). Minor polypharmacy implies simultaneous intake of two to four medications, whereas major – to five and more. It was suggested, and then scientifically proved that the incidence is higher for minor polypharmacy comparing to major. In fact, major polypharmacy appeared to be at its peak in the age group that consisted of persons 80-89 years old. Figures 1 and 2 demonstrate the incidence of minor and major polypharmacy among men and women of various age groups.

Furthermore, the above study had determined that females had 50% more chances of subjecting to polypharmacy, comparing to males. These results stress the importance of dealing with polypharmacy, especially among elderly patients, where this problem arises in the most visible way. According to Lassen (1989), 90% of the prescription medications are prescribed on the account of general practitioners (GPs). It is believed that most GPs are well aware of possible incorrect use of the prescribed drugs. It is also possible that the drugs will be given to members of the family/friends, to whom they can do much harm. Lassen (1989) had conducted statistical research, revealing that many treatments fail due to drug non-compliance. This is true, especially when the patient is prescribed more than five drugs (Dukes 1993). According to Lassen’s research, 33.3% of all patients comply with the treatment regimen partly, and another 33.3% do not comply whatsoever. It is possible that the patients are not well enough informed of their drugs, which makes them fail to follow the correct treatment plan. It is vital for PCDs to ensure that their patients are practicing rational medication treatment. This means that they are taking drugs in a suitable manner, according to the clinical necessity, corresponding to doses that agree to individual requirements, during an adequate timeframe. At this, the price of medications should be minimal for the patient, as well as for society as a whole.

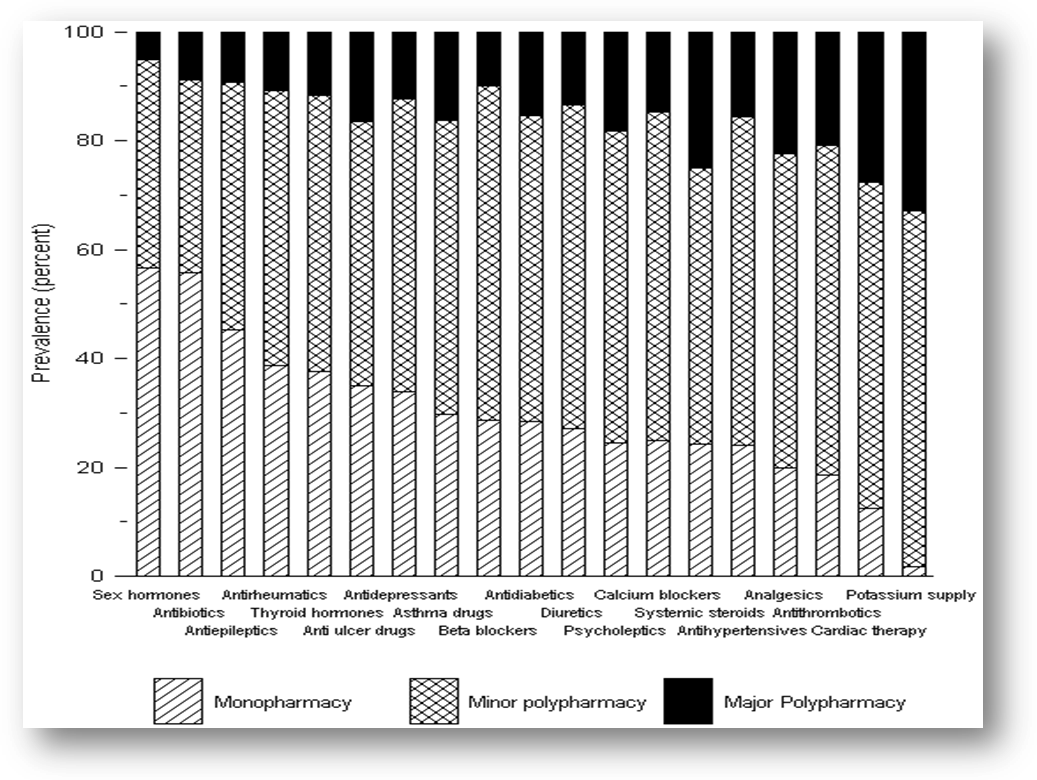

It appears that the most popular prescription medications are cardiovascular, antiinfectives, neuroleptics, antidepressants, and urinatives (Hogstel, 1992; De Maagd, 1995). Such medications as laxatives, analgesics, antacids, cough products, acetaminophens, and vitamins are the most common over-the-counter drugs (Hogtel, 1992). Many prescription drugs are now being converted to over-the-counter medications; therefore, additional medication categories are constantly appearing (Miller, 1996). The elderly population frequently suffers from chronic conditions that require multiple drug treatments and is therefore disposed toward immoderate drug use (Hess & Lee, 1998). Figure 3 reflects the profiles of utilization for various popular drug classes, as well as shows the amount of multiple simultaneous individual drug use. According to this chart, only 1% of potassium supplement users were subjected to monopharmacy. 66% of these individuals were subjects of minor polypharmacy, and 33% — major polypharmacy. It demonstrates that polypharmacy is a frequent occurrence among those receiving cardiac, antihypertensive, antithrombotic, and analgesic medication. Contrariwise, the majority of monopharmacy subjected patients were users of sex hormones and antibiotics. These data point out the issue addressed in the introduction of this article. It is very common that elderly people are prescribed treatment for a few conditions. The most common cause of polypharmacy is an attempt at the simultaneous treatment of several disorders. Such efforts elevate the risks of adverse drug reactions and interactions. The prerequisites of polypharmacy are primarily polyorgan pathology, prescribing methods of general practitioners (GPs), and access to multiple care providers, each prescribing similar classes of medications. Another important polypharmacy-inducing factor is the practices and convictions of the elderly. Many of them tend to keep and hide their old medications, stating that their drugs are not expired. Sometimes, when such persons are admitted to a hospital, they sneak in their old medication, and if the provider is unaware, new medication of the same kind is ordered and the patient can end up with a double dose of the treatment. This calls for the physicians to raise patient’s awareness of basic drug action mechanisms and the negative consequences of multiple medication intake.

Because medications and environmental toxins are cleared in the body through the same biologic mechanism, there is also a concern that those subject to polypharmacy are at high risk of adverse reactions between the drug and environmental toxins, as such toxins may induce or inhibit metabolic enzymes (Thummel and Wilkinson 1998; Youssef and Badr 1999) that are responsible for processing pharmacologic agents (Shimada et al. 1994). Intake of multiple drugs by an individual may also cause competitive displacement in the plasma, therefore affecting plasma protein binding (Herrlinger & Klotz, 2001; Mayersohn, 1994; Rolan, 1994). Aside from the dangerous effects of polypharmacy, it is possible for polypharmacy to be rationally used by clinicians (Preskorn 1995).

For example, if a need for co-pharmacologic treatment of several co-morbid illnesses that are pathophysiologically distinct exists, or for treatment of an adverse effect caused by the primary medication, use could be valid. In psychiatry, polypharmacy could increase the primary treatment effect with another drug (adding desipramine to serotonin reuptake inhibitor when treating major depression), or to treat different phases of an illness (combining a mood stabilizer with an antidepressant when treating depressive episodes in bipolar patients).

Possible Suggested Interventions

Carlson (1996) underlines the importance of intervention by PCDs in order to remedy the issue of polypharmacy in the elderly. He suggests that PCDs must develop proficient prescribing habits that will help to resolve side effects, preventing adverse drug reactions, lower pharmacy expenses, and improve treatment compliance. In order to develop such habits, there is a need to implement approaches that enclose medication disclosure, side effect recognition, drug identification, review of treatment, as well as relevantly monitored and thoughtful evidence-based reduction of numbers of medicines and their doses. Stewart and Cooper (1994) have a similar point of view. In their work, they state that in order to reduce polypharmacy in the elderly population, it is essential to implement patient education, regulatory interventions, continual disease, and drug monitoring, physician education, and various feedback systems. Cohen (2000) states that adverse drug reactions are leading to morbidity and mortality causes in elderly patients. Therefore it is important to prescribe minimal effective doses. This will help prevent adverse drug reactions, minimize side effects, and increase compliance rates. In his article, Cohen prescribes the lower effective doses for various common medications. Fifty hospitals in Massachusetts have introduced a preventive measure called medication reconciliation (Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2006). Its goal is to coordinate the medications that the patient is taking upon admission or discharge from the hospital as well as upon every visit to a doctor. This is done by collecting the complete medications list on admission, coordinating with the patient the home medications list, and using this list when writing a prescription order. This reconciliation must be done in a short period of time (no longer than 24 hours after admission), besides the advice of a pharmacist should be available at all times.

Discussion

It is just as difficult for the GP to control the polypharmacological treatment, as for the patient to comply with it. Therefore, it is essential that GPs must enter into their notes all prescriptions. The risk of polypharmacy is especially high when the elderly patient suffers from multimorbidity and has to take his medications at different times of the 24 hour period (Hemminki 1975). However, there are several interventions that could be taken for the purpose of polypharmacy prevention. There is a certain need for evidence-based clinical recommendations, which are systematically developed documents that contain information on diagnostics, prevention, and treatment of illnesses that will assist PCD in making correct clinical decisions, especially concerning the choice of treatment medication. The implementation of evidence-based clinical recommendations into practice is of crucial significance for a rational drug prescription for the elderly. Clinical recommendations should be developed according to levels of healthcare (primary, specialized, and highly specialized), and enclose priority diseases and syndromes that are most prevalent in the elderly age, as well as have the largest fractions in the mortality rates, being the cause to the greatest amounts of disabilities.

It is also essential for physicians to be provided with a source of independent information concerning medications. It is a common occurrence that pharmaceutical companies are the only source of information on the drugs they produce. Providing PCD with relevant independent information that draws on the advantages and benefits of certain medications, as well as their potential disadvantages and harmful consequences plays a key role in rational prescribing of medical treatment. Such independent sources must contain information on available and permitted usage medications that are recommended for the treatment of the most prevalent diseases among the elderly population. These drugs must be selected based on a clear methodology, and recommended by experts of pharmacological and therapeutical fields. This source should become the national standard for selecting and rationally using medications based on the consensus of leading professionals. The information must also draw on basic recommendations concerning the prescription of drugs for the elderly, and clinical data concerning separate medications recommended for treating the most common conditions of the elderly population. It should include recommendations on the rational treatment usage, international trade names of drugs, regulatory-legal information, as well as a summary of clinical evidence-based medical recommendations. Other important aspects that must be embraced in this source are the coverage of drug interactions, prescription of medications during kidney and liver disorders, submission forms for informing of adverse drug effects and drug quality issues, additional diagrams, and formulas for calculating drug doses. This information source may be the basis for the development of various formularies for different levels of healthcare. As the information concerning drug actions is changing constantly, this formulary must be updated annually.

Results and Their Analysis

It was discovered that there are several factors as well as various patient profiles that contribute to polypharmacy. These factors include age and gender, health problems, and multimorbidity. The results of the current literature review have shown that polypharmacy is much more common in females and increases with age, as chronic disease prevalence increases as the people grow older, providing an indication for additional therapy. It is visible that older age is a good indication of polypharmacy. It also became clear that female gender combined with old age is an evident predictor of polypharmacy, as in general there is a higher level of drug use among women, than men. Polypharmacy may as well be caused by treating diseases that are coexistent. It was revealed that the majority of those subjected to polypharmacy are treated with different main classes of medications, which points to multimorbidity. The fact that 80% of individuals over 65 have at least one chronic condition indicates high polypharmacy risk in this cohort. These tendencies can be partially explained by the health system, which is somewhat responsible for high polypharmacy prevalence. It is more likely that those with a chronic condition shall make more frequent visits to the doctors, and get prescribed different treatments more often.

Findings

It appears that some researchers define polypharmacy as the simultaneous use of more than five drugs (Fick et al., 2003), whereas others claim that polypharmacy is the use of more than two types of medications at the same time (Preskorn 1995). A study carried out at the Odense University, Denmark suggested a classification that breaks down polypharmacy into minor (taking 2-4 medications) and major (5 and more medications) (Bjerrum 1998).

The study demonstrated that the incidence of minor polypharmacy was higher than that of major polypharmacy, and the incidence of major polypharmacy was the highest in the 80-89 age groups. It also showed the tendency of women in all age groups to be about 50% more inclined towards polypharmacy than men. It is a known fact that general practitioners (GPs) are accountable for prescribing around 90% of all prescribed drugs, and most of them are aware that not all medications will be used correctly, and some drugs will be given to other individuals, for whom they are not appropriate. Studies have revealed that only 33 % of those treated by GPs comply with the suggested treatment (Lassen 1989; Peck and King 1982). One-third of all patients do not comply at all, and the other one-third only partly. This drug non-compliance correlates to the amount of medication used: when the patient is prescribed more than five drugs, the rate of treatment failure rises (Dukes 1993). The contributing factor to non-compliance may be elderly patient’s insufficient knowledge of their medication.

Conclusions

Addressing the issue of polypharmacy is aimed at making physicians aware of the problem, and preventing elderly patients from taking the unneeded medication in ambulatory care, emergency care, and inpatient services. The key positions that will assist physicians in more rational use of medications by their patients are good clinical recommendations, lists of essential medications, problem-oriented drug therapy education of the pre-graduate doctors, obligatory career enhancement and training, and most importantly – implementation of formularies containing independent comprehensive information on various types of pharmaceutical treatment.

References

Bjerrum, L. (1998) Pharmacoepidemiological studies of polypharmacy: [Electronic version]. Methodological issues, population estimates, and influence of practice patterns. 2007. Web.

Carlson, J. E. (1996) Perils of polypharmacy: 10 steps to prudent prescribing. Geriatrics. 51(7), 26-30.

Cohen, J. S. (2000). Avoiding adverse reactions. Effective lower-dose drug therapies for older patients. Geriatrics, 55(2), 54-6, 59-60, 63-4.

Darnell, J. C., Murray, M. D., Martz, B. L. et al. (1986). Medication use by ambulatory elderly: an in-home survey. J Am Geriatric Society, 34(1), 1.

DeMaadg, G. (1995). High-risk drugs in the elderly population. Geriatric Nursing 16(5), 198.

Dukes, M. Introduction. In: Dukes MNG, ed. (1993). Drug utilization studies: methods and uses. European Series No.45. Geneva: WHO Regional Publications, 1-4.

Ebersole, P., & Hess, P. (1998). Toward Healthy Aging: Human Needs and Nursing Response. St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

Fick, D. M., Cooper, J. W., Wade, W.E., Waller, J.L., Maclean, J.R., & Beers, MH. (2003). Updating the Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. Arch Intern Med, 163, 2716-2724.

(1992). Clinical manual of gerontological nursing. (Hogstel, M.O., Ed.) St Louis: Mosby.

Herrlinger,C., & Klotz, U. (2001). Drug metabolism and drug interactions in the elderly. Best Practice Res Clinical Gastroenterology, 15, 897-918.

Lassen, L. C. (1989). Patient compliance in general practice. Scand.J.Prim.Health Care, 7, 179-180.

Miller, C. A. (1996). Drug consult: multiple choices in over-the-counter drugs. Geriatric Nurse. 17(5).

Peck, C.L., & King, N.J. (1982). Increasing patient compliance with prescriptions. JAMA 248, 2874-2878.

Preskorn, S. H. (1995). Polypharmacy: When is it rational? Journal of Practical Psychiatry and Behavioral Health, 92-98.

Prybys, K. M., Melville, K. A., Hanna, J. R., & Gee, P.A. (2002). Polypharmacy in the elderly: clinical challenges in emergency practice: part I: overview, etiology, and drug interactions. Emergency Med Rep, 23(11).

Routledge, P.A., O’Mahony, M. S., & Woodhouse, K. W. (2004). Adverse drug reactions in elderly patients. Br J Clinical Pharmacology, 57, 121-126.

Shimada, T., Yamazaki, H., Mimura, M., Inui, Y., & Guengerich F. (1994).

Interindividual variations in human live cytochrome P-450 enzymes involved in the oxidation of drugs, carcinogens, and toxic chemicals: studies with liver microsomes of 30 Japanese and 30 Caucasians. J Pharmacology Exp Thor, 270, 414-423.

Stewart, R. B., Cooper, J. W. (1994). Polypharmacy in the aged. Practical solutions. Drugs Aging, 4(6), 449-61.

Thummel, K., Wilkinson, G. (1998). In vitro and in vivo drug interactions involving human CYP3A. Annul Rev Pharmacology Toxicology, 38, 389-430.

Youssef, J., Badr, M. (1999). Biology of sensescent liver peroxisomes: role in hepatocellular aging and disease. Environ Health Perspective, 107, 791-797.

Abstract

Polypharmacy is a major problem that can affect anybody, but it is the most common to the elderly population. Concept of polypharmacy encloses the use of five or more medications at the same time, prescription of more medications than required, and prescription of medications which are inappropriate. Effects of polypharmacy include overmedication, drug interactions that may cause over- or under-dosing, and possibly a lethal outcome. Polypharmacy is prevalent among the elderly population due to higher manifestation of chronic diseases that rely upon various medications, as well as reduced level of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic functioning within this age group. This article analyses the literature available on this subject, and addresses the issue of excessive drug use suggesting how it can be avoided by primary care doctors whose task is to master the skills required for polypharmacy prevention. Addressing the issue of polypharmacy is aimed at making physicians aware of the problem, and preventing the elderly patients from taking the unneeded medication in ambulatory care, emergency care, and inpatient services.