Abstract

The thesis study aims at demonstrating that a career community pharmacist can practice as an effective clinician in a prescribing role treating patients in a primary care setting. The introduction of advanced and enhanced community pharmacy services enhances the need for pharmacists to integrate into primary care medical services. Non-medical prescribing, through the training with and subsequent prescribing within primary care, can incorporate community pharmacy into the primary care team if a satisfactory level of practice can be demonstrated. Treatment outcomes and standards of patient satisfaction with a pharmacist-led clinic were compared with the normal care of patients with hypertension at a Medical Centre. Pharmacist non-medical prescribing forms the core of the study and the historical devolution of prescribing rights will be considered as there are several levels of autonomy and range of medications that are available.

Introduction: Evolution of the Pharmacists in an Independent Prescribing Role

The pharmacy profession has developed from the earliest knowledge of herbal or mineral preparations that we’re able to offer the possibility of improving the health of a patient. The early pharmacist’s role, as it is understood today, was to prepare the medication in a form that made it possible for the patient to use these early drugs. Pharmacy practice required the combination of physical chemistry and botanical knowledge with the emerging medical health sciences to produce useful and probably effective drugs. There are many elements to the development of professional status for an occupation. For pharmacy, there is a specialized knowledge necessary initially, the ability to compound medicines that were required in order to be able to perform the role. Professional bodies, such as the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, were established to control entry into a pharmacy and ensure standards of education and practice were maintained.

As knowledge of drugs increased in the 20th century, a significant proportion of the traditional medicines were found to be either ineffective or potentially dangerous. Drug research and testing allowed pharmaceutical manufacturers to discover or design more effective medicines, which due to their potency required accurate control of the dose taken by patients. This led to one of the major features of medicine developed in the 20th century, the mass production of drugs into single-dose preparations such as tablets and capsules. At the start of the 20th century, pharmacy supply of medication usually required the physical preparation of an individualized medication according to a recipe ordered by a doctor for a specific patient. By the end of the century, most medication supplied from community pharmacies was in the form of mass-produced tablets and capsules.

The modern pharmacy profession has grown out of the supply of medicinal products to a population that could not afford the services of the early doctors. These medicines required preparation by mixing active, probably poisonous, ingredients with a variety of additional substances to produce an acceptable commercial product. These early medicines were then recommended for the treatment of specific ailments by the pharmacist and if successful, could lead to an increased reputation for the pharmacist or his ‘patent’ medication. The pharmacy profession has changed dramatically since the early 1800s when some chemists and druggists began to work together to promote the pharmacy profession. By 1841, this led to the formation of the Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain by the leading pharmacists in London. Legal changes recognized the role of the Pharmaceutical Society to set professional examinations and register pharmacists under the Pharmacy Act 1852, without defining the professional role. Subsequent legislation in 1868 effectively gave pharmacists the right to sell, compound and dispense poisons with the Pharmaceutical Society being given the role of prosecuting pharmacists in cases relating to poisons. The preparation of safe stable medicines by the compounding of potentially poisonous chemicals and plant products was a key component of early pharmacy practice.

The professional practice of pharmacy has changed considerably over the past 40 years across all sectors. Most of the pharmacists in the United Kingdom practice in the community or retail sector, supplying medication to the public through over-the-counter (OTC) sales or by supply in response to a prescription from a medical or dental prescriber. In the UK there has been a division of the prescribing of medicines, largely under the control of the medical profession and dispensing normally by pharmacists but in some rural situations by dispensing doctors. In 1968 the legal classification of medicines was introduced with the safest medicines being labeled as general sales list, ‘GSL’ available to be sold by anyone, ‘P’ medicines which were only to be sold in pharmacies or prescription-only medicines, and ‘POM’s, which could not be obtained without a doctor’s prescription.

While there has been a steady process of change in the retail aspects of community pharmacy, the changes in dispensing economics have been achieved quite infrequently by changes to the NHS dispensing contract. In 1978, the rate of change in business organizations was expected to be a minor change each year and a major change every four to five years. Most probably, for most business sectors the rate of change has markedly increased over the last 30 years. In contrast, the changes to the dispensing contract have in the past occurred only once in a generation.

Present Scenario

At present, it is apparent that the development of manufactured medicines does not require a pharmacist to practice the medication compounding skills that were crucial to a pharmacist one hundred years ago. Pharmacists have found it almost compulsory to attain new skills to allow it to retain its professional integrity as it moves into the 21st century. The basis of professional status and how the profession of pharmacy has transformed from product-focused physical chemistry expertise to a patient-centered clinical role is the central view of this section. General dissatisfaction with the levels of professional practice in pharmacy, arising from a reduction in the exercise of medication compounding skills, led to an intellectual debate in the late 1970s and 1980s. It was then claimed by some academics that pharmacy might have lost the right to claim professional status. In the USA, Hepler and Strand believed that the reduction in the use of dispensing skills undermined the right to professional recognition. (Hepler C D and Strand L M 1990).

Pharmaceutical care in USA

‘Pharmaceutical Care’ was introduced in the USA hospital pharmacy sector and was defined as “the care that a given patient requires and receives which assures safe and rational drug usage” (Mikeal et al. 1975). This led to pharmacists being given patient counseling roles on hospital wards to enhance concordance with the medication at the hospitals. Advice on how to respond to the potential adverse effects of medication and thus decrease avoidable hospital admissions was an early focus of this clinical role. This role was further extended into a ward pharmacy role where pharmacists began to give advice on the choice of medication as it was prescribed to reduce the number of prescriptions for preventable adverse drug reactions with a significant decrease in the rate of adverse drug effects.

While the clinical roles were being introduced in hospital pharmacies, there was not much change in the community pharmacy sector. The community pharmacies, in the latter part of the 20th century, continued to perform the medication supply role for most United Kingdom citizens whether providing medication in accordance with a prescription, National Health Service or from a private doctor, or by over-the-counter sales. As the National Health Service pharmacy contract did not provide for any non-medication supply roles for community pharmacists, it might not be surprising that for many years little progress was made towards developing new community clinical roles.

There are several reasons for the lack of willingness to accept the new clinical practices seen in hospital pharmacy practice by the community pharmacy sector. Some of the major factors that hindered change were the lack of financial incentive, the lack of a unified profession, and low levels of participation in professional education after qualification as a pharmacist.

Pharmacy Contract with National Health Service

The community pharmacy contract with the National Health Service was initially based on the assumption that community pharmacy in the UK was a mixed role business. The pharmacies often developed a significant proportion of their income from commercial activity, such as by selling over-the-counter medicines, toiletries, photographic goods and baby care products. On account of this commercial activity, the National Health Contract initially paid pharmacist contractors a small fee for dispensing a prescription item and an element of profit, or on cost percentage, with additional fees for actually compounding prescription medication. While some pharmacists adopted a more clinical approach to professional practice, there was no clause in the National Health Service contract to reward this. The community pharmacists in the 1960s and 1970s mostly used to work as sole proprietors of independent businesses with little contact with their professional peers. The local pharmacists were normally viewed as business rivals and this did little to encourage a unified approach by the profession for developing new roles. It is probable that the failure of the Nuffield Inquiry to result in any significant change in the practice of pharmacy was on account of the lack of a unified professional voice calling for professional development. It will be observed afterward that the creation of a pro-change attitude within the community pharmacy sector was crucial to the agreement of the new pharmacy contract. At the same time, the need for continuing professional education was being reviewed. An inquiry commissioned by the government led to the adoption of an understanding that pharmacists and their staff should be required to keep their professional knowledge up to date with the latest developments and scientific know-how. Previously, post-graduate education was not compulsory for the profession and most pharmacists could either pick up what education they felt they needed from the Pharmaceutical Journal or allow their knowledge to be based on their pre-qualification university education.

In order to allow the community pharmacy to move away from the image of being shopkeepers, the on-cost or profit element of the medication dispensing process was removed. Instead, the pharmacists were paid a dispensing fee and a practice allowance which duly recognized the role the pharmacists played in public health education and medicines advice linked with over-the-counter sales. It had been proposed that amendments would be made to the supervision of pharmacies which would have allowed the pharmacists to delegate the dispensing process to their staff but this proposal was rejected by the profession. In the absence of an agreement on changing the supervisory rules which required the presence of a pharmacist in the pharmacy at all times, it was impossible to introduce new professional roles. It was to be a generation before the next major change which happened in community pharmacy arrangements with the National Health Service. The community pharmacists in an independent prescribing role in the General Practitioner practice, therefore assume greater significance. The broad knowledge base of medicines of the pharmacists also enables them to support patients with complex therapeutic regimes. Using the pharmacist prescribers has helped to improve the patients’ knowledge and compliance, which should lead to improved outcomes.

National Initiatives in Healthcare

With a number of national initiatives in healthcare being developed in the UK, added to those that are already part of routine care, there will be a significant impact on the way healthcare is delivered in the primary care setting. Some of these initiatives include Our Health, Our Care, Our Say and the Care Closer to home agenda, thus increasing the number of clinical domains in the new general Medical services Quality and outcomes Framework (QoF), and the commitment to increase primary care access for patients at evenings and weekends. Non-medical prescribing is thus an excellent way to maximize the skills of the existing staff in the National Health Service (NHS) to support the delivery of the NHS agenda and initiatives in the country.

Models of pharmacist prescribing in UK

Health Demographics of UK Population

At present, around 12% of the population in the UK, with some variance amongst regions and ethnicity, has hypertension, thus making it one of the largest treatable medical problems seen within primary care. Poor control of hypertension leads to several ailments such as stroke, diabetic complications and heart attacks. “…having high blood pressure is an important risk factor for developing stroke or heart attack in later life” (Bpassoc 2009). The increasing workload in the Healthcare segment due to demographic changes and lower treatment thresholds mean that the use of clinicians other than General Practitioners (GPs) for its management will be essential.

The hospital pharmacists, working at the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK, are ideally placed to be prescribers in a wide variety of clinical specialties. The hospital pharmacists have both a broad knowledge of medicines and a depth of specialist knowledge that has been gained through experience and postgraduate qualification. The medical records can be easily accessed, and they are able to monitor closely, the progress with therapy, and with the support of other clinicians including consultants. The specialist pharmacist roles allow the outpatient appointments and clinics to be managed by non-medical staff, with ready access to medical staff if necessary, which increases the clinical skills of specialist pharmacists, thereby improving team working and increasing access for patients.

Role of independent prescribing pharmacists in the care homes

The role of independent prescribing pharmacists in the care homes also assumes great significance. The National Service Framework for Older People describes how older people are most at risk of long-term conditions, non-elective hospitalization, falls, and other adverse events associated with medicines. At present, there are around half a million older people living in care homes in the UK, and they receive up to four times as many prescription items as those living in their own homes. The service users in the care homes are considered to be well provided for in terms of social and physical needs but it is also important not to overlook the need for person-centered healthcare. The role of pharmacists in Nurse independent prescribing in a walk-in center and out-of-hours care is also quite significant. At present, there are just over 90 walk-in centers across the United Kingdom that open for at least 15 hours a day, 365 days a year. The Walk-in centers are led by nurses and they generally deal with minor injuries (for example sprains, cuts) and minor ailments (for example allergies, pain, rashes).

The out-of-hours services are commissioned to provide urgent care outside core surgery hours. Under the new General Medical Services contract, the General Practitioners (GPs) are not required to provide 24-hour care for patients, so alternative providers operate a variety of services to allow patients to get medical advice and care at all times. The out-of-hours services are commissioned by the government to provide unscheduled care to patients outside core surgery hours, thus enabling the patients with access to medical care and advice at all times. The success and the expansion of the prescribing team are mainly due to the support of the medical director, lead nurse and the GPs who make up the out-of-hours team of clinicians. The primary care trust’s non-medical prescribing lead also supports the students by coordinating places on the course, placements and continuing professional development to ensure that all non-medical prescribers are able to keep up to date with therapeutic developments. Traditionally, the walk-in centers used a range of Patient group Directions to supply medicines, which could be time-consuming in terms of management and stock control. Having nurse independent prescribers at the out-of-hours centers means more patients have their episode of care completed by a nurse, and nurses can treat patients from outside the area who need prompt access to repeat medication. This flexibility is even more beneficial in the out-of-hours setting, where patient needs are often more wide-ranging.

Several General Practitioners (GPs), a pharmacist and a nurse have worked together to produce Clinical Management Plans for the patients. The Clinical Management Plans provide a framework in which to carry out medicine reviews, and the authority to make changes to medicines where necessary. The collaboration of three different healthcare professionals producing the Clinical Management Plans gives added value, with each person sharing and supporting the knowledge and expertise of the other. The only key challenge faced was acceptance by care home staff, although once relationships were built up, this ceased to be a challenge.

Evaluation Report-A study

A published evaluation report showed that the project might have contributed to a 32% reduction in falls, 60% reduction in fractures and 7% reduction in hospital admissions resulting in a better quality of life for service users, and significant savings in direct and indirect health and social care costs. The call-out rate for the patients’ General Practitioners (GPs) also reduced by more than 85%, leaving the GPs with more time to spend with patients at the surgery. Quite indirectly, these savings more than compensated for the costs of providing the service and should be of interest to Practice-Based Commissioning groups. The service would become even more efficient and effective when the pharmacists involved are qualified as pharmacist independent prescribers.

Independent nurse prescribing by the pharmacist in sexual health services also has great significance. The sexual health services of the United Kingdom are a key priority for the National Health Services (NHS), with sexually transmitted infections and HIV cases continuing to rise. At present, there are around 80,000 people living with HIV in the UK, with annual growth in diagnoses between 7,000 and 8,000. It is also estimated that close to 30% of people with HIV are unaware that they carry the virus. The advances in the treatment of HIV mean that patients are able to live normal lives and have a normal life expectancy which, with the associated conditions of older age, will lead to much greater numbers of patients with complex prescribing needs. Ensuring that the patients are able to discuss their medical therapy and be proactive on their own care is an essential component of HIV care, where patients must be compliant with at least 95% of doses to ensure that the drug has maximum efficacy. Poor adherence and increased drug resistance ultimately lead to the patients requiring newer and highly expensive anti-HIV agents. The pharmacists in an independent prescribing role also play a crucial part in the Nurse independent prescribing in primary and secondary care related to dermatology ailments. Dermatology is one of several clinical areas that are rightly placed to use the expertise of specialist nurses and pharmacists with a prescribing qualification. The long-term, and often visual, nature of dermatology conditions and ailments means that many patients benefit from the person-centered care that caters for both their physical and psychological needs. Increasing demands for several services, for example from higher rates of skin cancer and allergic conditions – highlighted in the NHS Plan – have placed greater demands on prompt access to dermatology services across England.

Role of the pharmacists in Nurse independent prescribing in the community and outpatients

The role of the pharmacists in Nurse independent prescribing in the community and outpatients especially related to epilepsy holds some special significance. Epilepsy is a very common chronic disabling condition of the nervous system, which affects nearly one in 30 people at some time in their lives. Approximately 1,000 people die every year as a result of epilepsy, of which 500 deaths are sudden or unexplained. According to ‘Nice Guidelines ’, epilepsy specialist nurses should be an integral part of the network of care of individuals with epilepsy. Their crucial roles are to support both epilepsy specialists and generalists, and thus ensuring continued access to community and multi-agency services, and provide information, training and support to patients, families and carers. The National Sentinel Clinical Audit of Epilepsy-Related Death found out that 20% of adults and 45% of children with epilepsy as having inadequate medicines management. The report also recommended that all patients should be reviewed annually as a minimum, together with access to a specialist nurse. The Patients with unstable epilepsy such as prolonged or frequent seizures need immediate attention to their medication so as to reduce the possible harm to the patient, as well as the disruption to their daily lives and the possible consequences of a poorly controlled medical condition. Being able to customize the medicines regimens to an individual patient’s condition minimises the risk of side effects and increases efficacy, thereby making it much more likely that the patients can continue to work and look after their children. The Reviews of medicines of the patients and the subsequent follow-up prescribing system can enhance the patient compliance and quality of life; for example, by addressing formulation, frequency of dosing and side effects.

The existing program of the NHS in England: ‘The Operating Framework 2008/09’ to deliver 48-hour access to genitourinary medicine (gUM) clinics means that these services may need to increase capacity. Using the existing staff of the pharmacists with enhanced qualifications and skills may help the NHS to achieve this objective.

In Great Britain, the skills and competencies of non-medical health professionals are increasingly being used to improve patient access to medicines and to reduce doctors’ workload (Stewart 2010). The final Crown Report in March 1999 proposed that non-medical health professionals should be permitted to take on additional prescribing responsibilities. The report defined two new types of prescribers: the independent prescriber and the dependent prescriber. The Health and Social Care Act 2001 (Section 63) allowed for the introduction of dependent prescribing (implemented into practice as supplementary prescribing) status for non-medical health professionals, including pharmacists. Pharmacists with at least two years’ experience as a pharmacist can undertake SP after training at a higher education institution (200 h at the degree/masters level over 25 days) and completing a ‘period of learning in practice’ (PLP) (supervised training under a designated medical practitioner for a minimum of 12 days) in accordance with the curriculum and assessment methods specified by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (RPSGB). Pharmacists working in various practice settings across Great Britain have been practising SP since March 2004. Published research on pharmacist prescribing is limited to the views of pharmacists from various practice settings and anecdotal experiences of the SP course and the implementation of SP. No national study has been published reporting the experiences of pharmacists relating to their SP course and implementation of SP. Such a study is critical to optimise future training programmes for pharmacist prescribing. Understanding perceived challenges to and benefits of SP implementation could inform policy makers, organisations considering implementation of SP service and pharmacists planning to undertake prescribing training. This study has explored the experiences and perceptions of early pharmacist supplementary prescribers in Great Britain. SP has been regarded as highly beneficial for both patients and pharmacists. Several logistical and financial barriers hindering the implementation of SP have been identified.

New Community Pharmacy Contractual Framework

Background Medicines are the most commonly used form of healthcare treatment. They provide relief from everyday ailments to life-saving interventions for acute illness as well as support for people with long term medical conditions such as asthma, or progressive illnesses such as arthritis or multiple sclerosis. Building on the NHS Plan, in 2003, the Department of Health (DH) set out its intention to increase the public’s choice of when, where and how to get medicines by: freeing up restrictions in England on locations of new pharmacies in the Government’s response to an Office of Fair Trading report: easing bureaucracy around repeat prescriptions; expanding the range of medicines that can be provided without prescription; promoting minor ailment schemes in pharmacies; increase the range of healthcare professionals who can prescribe. Many of these changes will be implemented through increasing the contribution that community pharmacists make to primary health care.

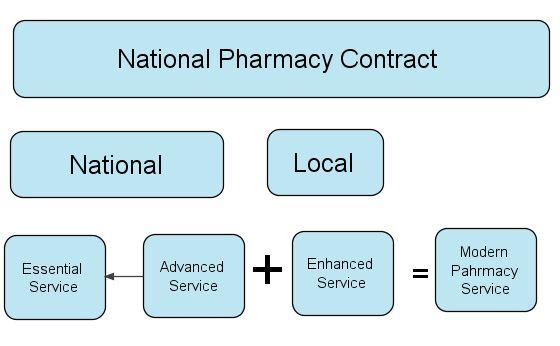

According to the new pharmacy framework, there are three stages of services namely, essential, advanced, and enhanced services. These three services are explained in the ensuing paragraph. Essential services are defined as those services that must normally be provided. Essential services include dispensing, repeat dispensing, disposal of medicines, promotion of healthy lifestyles, and provision due to these errors. These include motion of self care for patients with minor ailments and signposting for patients to other healthcare provision. Advanced services are those which require accreditation of the pharmacist providing the service (such as medicine use review) and/ or specific requirements to be met in regard to premises, such as private consultation areas. Enhanced services are local services such as minor ailment schemes and supplementary prescribing that will be commissioned by Primary Care Trusts, according to the needs of the local population.

Payment will be increasingly directed towards quality, not just dispensing volume, recognising that the pharmacies need a fair return for the services they provide. Medicines Legislation Act in the UK: The Medicines Act 1968 and Council Directive 2001/83/ EEC control the sale and supply of medicines. Once the medicines are authorized, they attain a legal significance. There are three classes of medicine: A new medicine is usually authorised as prescription only (POM). After some years use, if adverse reactions to it are few and minor, it is possible that it may be used safely without a doctor’s supervision. In situations where it is observed that ample safety is being taken, the medicine is authorized for sale by a pharmacist. Similarly, pharmacy medicines which have been safely used for several years may be reclassified for general sale (GSL). The Committee on Safety of Medicines plays an important role in reclassifying the medicines. In cases where reclassification is considered to be safe, public opinion is sought through the portal of MHRA.

Contractual Framework and its focus on the changing role of pharmacies: Community pharmacies are where most people have access to pharmacy services and where 73% of active pharmacists work. A new contractual framework between community pharmacies and the NHS was introduced in April 2005. While the old system emphasised the volume and throughput of prescriptions, the new framework focuses on the range of services that pharmacists provide for patients. These are divided into three levels – essential, advanced and enhanced. Prior to the new community pharmacy contractual framework, the granting of contracts to pharmacies to dispense NHS prescriptions was subject to the NHS (Pharmaceutical Services) Regulations 1992. Since the NHS accounts for the vast majority of all prescriptions, it is difficult for a pharmacy to run a viable business without such a contract. This effectively amounted to full regulation of market entry for new pharmacies. The Government wanted to offer patients more choice in where they get their prescriptions dispensed by making it easier to open new pharmacies. In 2004, it announced new rules to introduce criteria of competition and choice to the regulatory test, exempting the following types of pharmacies from the test: those in areas where consumers already go, such as large shopping developments; pharmacies intending to open for more than 100 hours a week; those in large one stop primary care centres; and internet and mail-order pharmacies that allow people to have medicines delivered to their home. The Government’s commitment to make medicines more readily accessible raises issues including access to medicines, the role of pharmacists, and access to patient information and pharmacies.

Who’s who in Community Pharmacy?

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (RPSGB) is the regulatory and professional body for pharmacists. The primary objective of the Society is to lead, regulate and develop the pharmacy profession. National Pharmaceutical Association (NPA) is the national body representing Britain’s community pharmacy owners. UK’s Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) supports and motivates the general practitioners to attain and uphold the standards of their profession to their utmost levels. The Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee (PSNC) represents community pharmacy on NHS matters. It negotiated the new pharmacy contractual framework with the DH and NHS Confederation.

The British Medical Association’s General Practitioners Committee (BMAGPC)

The BMA represents doctors from all branches of medicine all over the UK. Its GPC represents all GPs, to promote general practice and to protect its fundamental characteristics and interests. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) is the executive arm of the UK’s Drug Licensing Authority and is responsible for all aspects of the regulation of medicines in the UK. The Committee on Safety of Medicines (CSM) is an expert Committee that advises the Government on the safety, quality and effectiveness of medicines.

It is widely agreed that there are advantages to making more medicines available without prescription. However, some groups have expressed concern about how far this should be taken. The recent reclassification of a low dose of statin (simvastatin), a medicine that reduces cholesterol levels, is a case being analysed. Statins are currently prescribed to 1.8 million people. In 2004, the Committee on Safety of Medicines (CSM) advised that simvastatin should be available without prescription in a low 10 mg dose, but continue to be available as a POM to high-risk patients. RPSGB welcomed the decision. It believes that there is a clear public health benefit to be gained from making this medicine available without a prescription. However, others including RCGP, BMA GPC and the consumer organisation, disagree. BMA GPC is against the introduction of statins to the over-the-counter market for a range of reasons, including safety concerns. It suggests that even low doses can cause side effects, such as muscle damage, and thus considers it inappropriate to provide such medicines without a doctor’s supervision. Such safety concerns should be addressed by the CSM when it is considering its advice on an application to reclassify a medicine. Neither MHRA nor the CSM publish a report of the evidence considered and why their decision was reached. Some have questioned the benefits of wider access to medicines in general and to preventative medicines in particular. While the reclassification of simvastatin has been welcomed by the RPSGB, the medical profession has expressed doubts over the balance between safety and efficacy. For instance, the RCGP points out that the therapeutic benefit of 10 mg of simvastatin (a 27% reduction in risk of heart attack and stroke) only applies to those people at increased risk of heart attack or stroke in the first place. It is concerned that people taking the drug who are not at increased risk of stroke or heart attack may receive no therapeutic benefit while exposing themselves to the risk of side effects. RCGP is concerned that, in practice, it will be the ‘worried well’ who take preventative medicines rather than the people who may benefit most from them. It is worried about the psychosocial implications of an ever greater proportion of the population considering themselves to have some sort of health problem. DH argues that by extending access to such medicines it is giving people more choice about how they protect their health. Consider that patients who have a clinical need to take medicines such as statins should be able to take them on the NHS. Pharmacists are experts in the use of medicines and must complete a four year degree and one year’s practical training to qualify. It is widely agreed that better use could be made of pharmacists’ skills and knowledge; the new pharmacy contractual framework sets out the Government’s plans on how to achieve this. Because community pharmacists operate within a commercial environment, questions have been raised about whether they are best placed to decide if a patient requires a medicine and if so, which one? However, one of the key responsibilities within a pharmacist’s code of ethics is to act at all times in the best interests of the patient. Pharmacists are expected to assess whether a prescription or an over-the-counter medicine is appropriate. The public appears comfortable with a pharmacist’s dual roles of retailer and healthcare professional. In a survey more than half the respondents disagreed with the assertion that pharmacists sometimes recommend products that are not strictly necessary in order to make a sale.

New Schemes

Over the past five years a number of schemes have been established to better integrate pharmacists into primary care and the new contractual framework will further encourage this. In general these schemes have been considered a success and have been integrated into the new pharmacy contractual framework. They offer easier and faster access to services for people as well as reducing a GP’s workload. For example, the Care at the chemist scheme in Bootle resulted in a reduction in GPs’ minor ailment workload from 8.9% of consultations to 6.6%. Repeat dispensing by pharmacists is also likely to reduce GPs’ workloads. Currently about 75% of GPs’ prescriptions are for repeat medicines. Pharmacists can offer medicines usage review as an advanced service under the new contract. Here, pharmacists undertake a review (of both prescribed and non-prescribed medicines) with patients receiving medicines for long term conditions, to establish a picture of their use of the medicines. It is anticipated that this will help patients to understand why the medicines are prescribed for them, as well as identifying side-effects that they may be exposed to. Medication review and management can be complex as many older patients receive treatment for at least four different conditions, leading to concerns about how different drugs interact with each other. RCGP has thus questioned whether pharmacists’ training and access to patient records are sufficient to enable a safe review. However, the DH points out that pharmacists training does include drug interactions, and that there is evidence from pilot schemes that pharmacists can carry out medication reviews effectively. Furthermore, to be able to offer this service under the new pharmacy contractual framework, pharmacists must be accredited and will have to provide a report of the review to the patient’s GP.

Supplementary Prescribing and the Better use the Pharmacists’ Skills

Minor ailment schemes have included treatment for conditions such as athlete’s foot, earache, constipation, hay fever and cystitis. The interventions available to a pharmacist are usually of three main types: advice only; advice and supply of medicines over-the-counter; or referral to a GP. In the Care at the chemist scheme in Bootle patients requesting a GP appointment for minor ailments, such as earache, nasal symptoms, and cough, were offered a consultation at a pharmacy. 38% of patients were happy with this option and thought the arrangement was convenient. Patients who had not had the symptoms before preferred to see a doctor.

Supplementary prescribing, including repeat prescribing, is a sort of cooperation between a General Practitioner who assesses a patient’s ailment, another medical practitioner who monitors the patient and prescribes further supplies of medicines within an individual clinical management plan, and the patient who agrees to the supplementary prescribing arrangement. All pharmacist supplementary prescribers must undergo additional training, including a period of supervised practice. In a diabetes shared care scheme, GPs were able to refer patients with type 2 diabetes back to a pharmacist-led outpatient-clinic if complications developed. The pharmacist reviewed their treatment, altered their medicines according to laboratory results and offered patients advice and information. None of the patients in the shared care scheme were readmitted to hospital with diabetic complications in contrast to 25% of the patients in the control group. In a study of repeat prescribing in Dundee 81% of patients preferred it to the traditional system of requesting a prescription from their GP.

Usage of IT by Pharmacist

Information technology will play a fundamental part in helping pharmacists to provide new services. According to the National Pharmacy Association, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, and the Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee, the pharmacists should have more admittance to information pertaining to the patients so that they are able to offer secure and efficient service. The National Programme for IT including the NHS Care Records Service and electronic prescription service, from GPs to pharmacists, will address this. Over time the benefits of the electronic prescription service will include: increased safety; more choice and convenience for patients; better information for prescribers and dispensers on which to base clinical decisions; and reduced administrative burden in GP practices and community pharmacies. However, the NHS Care Records Service is not due to be fully implemented until 2010. Therefore, in the meantime, continuity and completeness of patient care will require good communication between GPs, pharmacies and the patient. Discussions as to what levels of access to patient information a community pharmacist may need are ongoing. The consumer group suggests that patients are likely to be more comfortable with community pharmacists having access to their NHS records where there is an existing patient-pharmacist relationship. Attitudes towards any pharmacist or pharmacy technicians and assistants having access are less certain. The new NHS IT infrastructure makes provision for restricting the information available to a healthcare professional depending on the service that the professional is providing. In addition, pharmacists are bound by their code of ethics to respect patient confidentiality. DH is planning to hold a consultation about pharmacists’ access to patient information.

Competition and community pharmacies

In 2003 the Office of Fair Trading (OFT) advised that the pharmacy sector should be deregulated. It suggested that relaxing the rules on where pharmacies can be located, including allowing internet-only and mail-order pharmacies, would save patients and the NHS money. The House of Commons Health Select Committee considered OFT’s recommendations but was not in favour of deregulation. The Committee considered that the OFT report had failed to take account of the wider role of pharmacies within the NHS. Similarly, the Government did not back a move to a fully deregulated system, but favoured opening up the market in England to more competition and choice. It announced new rules to do this in 2004. Reform of the NHS (Pharmaceutical Services) Regulations 1992 will allow market entry exemptions for large shopping developments, pharmacies opening more than 100 hours a week, large one-stop primary care centres and internet and mail-order pharmacies. The National Pharmaceutical Association (NPA) is concerned that some local community pharmacies will not survive such competition. It suggests that this could potentially lead to reduced availability and access to local services. Parliamentarians have also expressed concern that the changes do not fit with the Government’s plans to enhance the role of community pharmacies.

Pharmacists and their role in sales of medicines on the Internet

With the advent of new technologies and the internet, a new way of doing business has come into being. Prior to this, business, as usual, was done through shops. There were some products that could be ordered through mail but the quantum of such products was negligible. But thanks to the internet facility, now even pharmacies can have their own websites through which they can cater to the global customers. The following are the benefits of having a personalized website for pharmacies:

- By having an own website and uploading it through a reliable Search Engine Optimization (SEO) company, pharmacies can have a larger market base.

- The pharmacies can cater to mail orders throughout the world.

- The pharmacies can promote their specialities or expertise in any particular field to the worldwide public.

- It is very easy for pharmacies to be in contact with other businesses and the customers.

- It is a very cost effective way of doing business.

- The pharmacies can surf the internet in order to search for better and less costly drugs or their substitutes.

- The pharmacies can update their data by having information on the latest inventions of drugs and/or diseases and their cures.

- The pharmacies can have information on any scheduled or ongoing conferences and can apply for registration.

Buying medicines online or by mail-order offers potential benefits – for example to house-bound patients or those with an embarrassing health problem – and is likely to become increasingly popular. Internet sales can broadly be divided into legal and illegal. Illegal sites offer POM without a prescription. Predominantly they offer ‘lifestyle’ drugs such as Viagra (sexual dysfunction) and Xenical (weight loss). The MHRA Enforcement unit attempts to close down such sites but as many are based outside the UK they fall outside MHRA’s jurisdiction. Distinguishing legal from illegal sites is a major issue for customers. POM and P medicines should only be taken in consultation with a healthcare professional, in order that the appropriate product is prescribed; any side effects are carefully monitored and other medicines and treatments taken into account. As the advent of internet and mail-order pharmacies allows this interaction to take place remotely, the patient needs to be sure they are communicating with a qualified, registered professional. Likewise, the professional needs to be certain that they know the patient they are communicating with. RPSGB has set up a working group that includes government and other interested parties, to consider how the regulatory framework can be enhanced to provide adequate safeguards for people purchasing medicines on-line. The group will consider the need for an information campaign to increase public awareness and is expected to report within the coming year.

The Government is committed to expanding the role of pharmacists and making medicines more widely available to the public. The medical profession is concerned that increasing access to preventative medicines via reclassification may target the ‘worried well’ rather than those most likely to benefit. It is widely agreed that better use could be made of pharmacists’ skills and knowledge. The new pharmacy contractual framework should enable this, leading to easier and faster access to services for patients as well as reducing GPs’ workloads. Making the medicines more readily accessible raises the issues such as the role of pharmacies, pharmacist’s access to patient information, and access to pharmacies.

Introduction: PEST Analysis of Community Pharmacy

In recognition of the need for change in an industry it is important to consider the strategic position of the industry, whether it is in decline or growth compared to the wider market. Other factors which will influence the need for change consist of changes to the legal framework and social environment in which the pharmacy industry operates. Two most commonly favoured methods of analysing the business environments are SWOT analysis (The Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) and the PEST analysis (Political, Economical, Social, and Technological factors).The PEST analysis tool has been developed to assist with strategic business planning by allowing a macro-environmental assessment of trading to be examined. PEST analysis takes into consideration the Political, Economic, Social and Technological influences on the industry. The Political factors for most industries are restricted to legal changes, taxation and tariffs set by the Government, but in the case of pharmacy the Government influence extends into the economic factors. Other political factors affecting the community pharmacy are the laws of employment and the stability of the government. The economic factors responsible for the performance of a community pharmacy include the financial growth of the country or state, the rates of interest applicable, the prevailing rates of exchange and the rate of price increases. The Social factors represent changing customer and trade behavioural trends. Customer behaviours include the people being conscious about their wellbeing, the increase in population and the importance of safety that they have. Technological factors consider how innovation in practice using new processes and equipment will require change. The research and development activities being carried out make a lot of difference. By having an up to date R&D facility, pharmacies can keep up with the pace of development and the inventions being made in the field of pharmacy. The main factors influencing the need for change in the pharmacy profession have been given below:

Table 1: PEST Analysis of Community Pharmacy

Government Policies

Medication supply to patients in the United Kingdom comes under the legal regulation with pharmacies supplying the majority of the population. Pharmacy is an independent healthcare profession with its own representative and regulatory organisations. Since the establishment of the National Health Service the Government through the Department of Health has been the main customer for pharmacy services. The Department of Health of the UK determines the changes to the legal basis of medicines supply and in consultation with the Pharmacy Services Negotiating Committee, representing the pharmacy contractors, sets the remuneration levels for pharmacies contracted to the National Health Service. As dispensing volumes increased in the United Kingdom pharmacists have found it impossible to dispense all prescriptions unaided. It therefore became necessary to use supporting staff that have usually been taken from a medicine sales role to assist in dispensing prescriptions. Informal dispensary support members of staff have with appropriate training become qualified as “dispensers”, equivalent to the National Vocational Training Level 2. On completion of further training to National Vocational Training Level 3 dispensers can qualify as “dispensing technicians”. Professional registration at the dispensing technician level is now being encouraged and will soon be a statutory requirement. At present, community pharmacy practice requires that a pharmacist is able to supervise the activity of staff in making sales of medicines to the public or in dispensing prescriptions (Department of Health 1968). Technological changes necessitated by the introduction of computers and private video transmissions have made it possible to provide a level of supervision by a pharmacist from a remote location. The introduction of responsible pharmacist legislation enables the pharmacist to be absent from the pharmacy for up to two hours a day (Anon 2008). The legal supervision of medicine sales or supply still requires the personal presence of a pharmacist in the community pharmacy although this situation may change as a result of future legislation. A potential effect of remote supervision of community pharmacies could be that several low dispensing volume pharmacies could be supervised by a single pharmacist. If this does become an accepted model of pharmacy practice there would be a serious impact upon pharmacist employment.

The new community pharmacy opening has been restricted under the terms of the pharmacy contract regulations unless a pharmacy is open for one hundred hours a week. The supermarket groups in the UK had lobbied with the government for the right to operate pharmacies from within their stores for several years leading to an official review which recommended removal of controls {The Office of Fair Trading, 2003 13 /id}. A compromise for allowing all supermarkets to incorporate pharmacies was to require these supermarket applications to dispense to succeed if extended hours were offered thereby increasing public access to pharmacy services {Advisory Group on the reform of the NHS (Pharmaceutical Services) Regulations 1992, 2004 14 /id}. If it is assumed that a standard pharmacist is working forty hours in a week, these one hundred hour pharmacies would require two and a half full time equivalent pharmacists to supervise their operation. Unless the supermarket is located close to a doctor’s surgery it is unlikely that hourly prescription volumes will be high. The prescription volumes in the periods when the doctor’s surgeries are closed probably do not justify the presence of a pharmacist if it were not a contractual requirement. Remote supervision of these hours worked by the pharmacists would represent a major economy for the supermarkets and would reduce employment options for community pharmacists.

In a recent consultation document, the Government wanted to consider changes to pharmacy practice that might incorporate a move to dispensing technicians having a greater role in the supply of medicines under the “remote supervision of pharmacists” (Department of Health 2004). Pharmacist supervision of medicine dispensing has been an area of concern to the profession since a review (Nuffield Foundation 1986) following which it has generally been considered that for a pharmacy to be open required a pharmacist to be present. With the recognition of the dispensing technician qualification and registration of technicians, there has been concern that the Government would change the supervision rules. It is thought there may be changes planned to permit a pharmacy to operate with qualified technicians performing the dispensing roles with access to an offsite pharmacist to assist when necessary (Axon 2007). A willingness by Government to examine how other European Countries supply prescription medication could eventually lead to reduced pharmacist involvement in dispensing as some countries allow unsupervised technician dispensing (Department of Health 2004). Economically, pharmacy as a profession is in a weak position as the main customer for its professional services is the Government in the form of the National Health Service. The contract to supply prescription medicines under the National Health is on the basis of the cost of the medication plus a professional fee (Anon 2009b). This remuneration scheme allows the Department of Health to set an annual ‘global sum’ for community pharmacy payments which represents the profit element for supply of National Health Service prescriptions or services. After allowing for a basic practice fee to reward the public health advisory role and any additional pharmacy contract services the balance of the global sum is divided by the anticipated number of prescriptions dispensed to obtain the annual professional fee per prescription item. The remuneration system for prescription item costs is adjusted to allow for discounts obtained in purchasing medicines for supply on prescription from pharmaceutical wholesalers. Since the introduction of discounts on pharmacy accounts by the wholesalers the Department of Health has applied a deduction to avoid paying pharmacies above the actual ingredient cost plus a dispensing fee. This “cost plus” fee basis allows the Department of Health to reclaim any profits made from more efficient drug purchasing by community pharmacies. As discounts vary with the account value, the deduction of the Department of Health, changes from 5.63 percent, for less than 126 prescription items a month, to 11.5 percent for pharmacists dispensing 160001 or more items a month (Anon 2009b).

Profits through purchasing drugs at a discount or buying at a lower cost than that paid by the Department of Health to pharmacies are reclaimed following annual discount enquiries which compare costs expected by the Department of Health with actual prices paid by pharmacies (Anon 1999). When new trading opportunities occur, as in the example of parallel imported medicines (branded drugs sold in continental Europe at prices below UK wholesale prices and imported outside the normal wholesale system historically used by pharmacies) can make significant profits for community pharmacies. However, after a period of increased profitability the prices paid by the National Health Service are discounted to reflect real costs and following a discount enquiry the excess profits are reclaimed.

The Department of Health effectively controls the level of profit that can be made from dispensing services since it sets the global sum for pharmacy remuneration and this could be a threat to future pharmacy profitability if the global sum is reduced. Declining profits could result from future Government spending reductions as the Department of Health could be facing significant cuts (Sylvester, Thomson, & Elliott 2009).

The pharmacy contract has undergone few changes since the establishment of the National Health Service but was substantially changed by the New Contract in 2004. This new contract has divided pharmacy services into core, advanced and enhanced services. Core services revolve around the medicines supply role and account for approximately ninety nine percent of professional income. The dependence on dispensing is such that due to the decline of over the counter sales between 90% and 95% of the income of an average pharmacy is generated by the National Health Service contract.

The newly introduced advanced and enhanced services require the use of more clinical skills by the pharmacist but so far have not provided a significant financial reward. Funding for additional advanced services is included within a total remuneration, or ‘global sum’, of payments for National Health Service contracted pharmacy services. A future ‘new medication service’ will be made available as an advanced service potentially capable of increasing income for community pharmacies by £55 million a year. However, it appears to be at the expense of core service funding as the introduction of this service is not expected to increase the cost of pharmacy contract services to the National Health Service. Additional funding pressure results from the expectation by the Department of Health to be capable of year on year efficiency savings, as can be seen from the expectation that £110 million would be saved from the pharmacy global sum if the new medication service had not been introduced (Alexander, 2011 12 /id).

This financial pressure on core services could lead to the adoption of technologies which would reduce pharmacist involvement in the dispensing process. There is a threat to community pharmacist employment as a reduction in pharmacist time supervising dispensing could potentially reduce community pharmacist numbers if additional roles are not adopted and adequately remunerated. In order to increase community pharmacy professional income in the future it appears it will be necessary to extend professional practice beyond that covered by the standard pharmacy contract.

Value of OTC medicines

The value of OTC medicines and traditional pharmacy goods sold from pharmacies has declined over the second half of the 20th century as retail trade has gravitated towards supermarket shopping (Defra 2006). The pharmacy sector has also seen an increase in corporate ownership as a few multiple chains, the largest being owned by pharmaceutical wholesalers, have come to monopolise the retail sector (Tann and Blenkinsopp 2004). Supermarket chains have in recent years increased the range of items sold to include traditional pharmacy goods, cosmetics, baby food and over-the-counter medicines, reducing sales from community pharmacies despite an overall increase in retail sales in the country. This loss of sales has increased as supermarket chains are now incorporating their own pharmacies into their stores, thus taking ‘pharmacy only medicine’ sales away from traditional high street pharmacies.

The pharmacy profession was based on the compounding of medicines for supply to the public either on a doctor’s prescription or through recommendation by the pharmacist. However, the practice of pharmaceutical compounding skills has become increasingly irrelevant in the 21st century. Medical research has led to the adoption of ‘Evidence-based medicine’ increasing the use of treatments that research can prove to be both effective and safe. Evidence-based medicine seeks to utilise the most effective medication available based upon the results of modern research methods to remove individual clinician bias. Traditional medications in contrast have been prescribed based on the experiential prescribing of individual clinicians without the advantages of unbiased scrutiny.

The use of traditional compounded medicines has therefore declined as few of these products have ever been subjected to scientific review of efficacy. Some compounded medicines are described as being less suitable for use in the national prescribing guidance handbook, the British National Formulary, and this has further reduced the prescribing of these products (Anon 2008b).

During the 1980’s dispensary computer systems were adopted by community pharmacies for prescription labelling, stock control and recording patient’s medication records. Early experiences were based on the Apple II, and BBC microcomputer systems with the software loaded daily from a floppy disk. The ability to word process labels and the introduction of patient ready packs of medicines, medicines pre-packed in standard dispensing quantities with patient information leaflets, made repeat dispensing a dispensary assistant staff role. These dispensary assistants have evolved into dispensing technicians who are now being required to register in a similar way to pharmacists (Department of Health 2009). Newly developed drugs have normally been formulated into unit dose medicines which are themselves packaged in patient ready packs usually representing either a course of treatment or for more long-term treatments one month supply. This standardisation of packing has led to the development of computerised robotic dispensing systems which can rapidly select and label prescriptions (Swanson 2009).

When the electronic transfer of repeat prescriptions from doctors to pharmacies is operational, the use of robot dispensing systems may make dispensing a largely automated process. This automation already poses a threat to future employment of both pharmacists and dispensing technicians with one hospital pharmacy finding a reduction of 32 per cent pharmacist hours and 52 per cent dispenser hours required to perform the medicines supply function for their patients following the introduction of robotic systems (Roberts & Gray 2004).

In the second half of the 20th century there were changes in the practice of hospital pharmacy which led to the development of an enhanced clinical function with ward-based roles. Pharmacists started to advise the medical profession on medication, becoming recognised experts on drug therapies. To allow pharmacists to perform the new clinical roles many of the dispensing duties were delegated to suitably trained and qualified (dispensing) technicians.

In community pharmacy change has been more difficult to achieve. The profession’s core income is from dispensing services and for significant change to occur there is a requirement for the remuneration system to be changed. In the 1980s the Government commissioned a study to review the pharmacy profession and suggest future developments (Nuffield Foundation 1986). The profession was considered to have a potentially major role in self-medication and health education but needed to improve pharmacy staff training. While changes were made to the dispensing contract to recognise these roles the professional’s financial reliance remained on dispensing services.

The development of more clinical roles occurred at about the same time as the lengthening of the pharmacy qualifying degree to four years. This could potentially produce graduates with greater clinical knowledge (although ways to increase clinical education are still under review (Department of Health 2008)) and help engender a desire to practice in more patient orientated roles. Concern over the development of the profession among the pharmacist community led the Royal Pharmaceutical Society in 1995 to initiate a discussion process, ‘Pharmacy in a New Age’ (Longley 2006). A widespread dissatisfaction with the lack of professional development since the Nuffield report and a previous unwillingness to change entrenched practices was identified (Parkin 1999).

Prescribing errors – A concern and a research study

Studies carried out in the American hospitals suggest that prescribing errors occur in 0.4–1.9% of all medication orders written and cause harm in about 1% of all inpatients (Emmerton , Marriott, Nissen, & Dean 2005). No large scale studies of prescribing errors have been carried out in the UK, although studies of pharmacists’ interventions suggest that many errors occur and are subsequently remedied following the interventions of ward pharmacists. A recent report from the Department of Health recommended that serious errors in the use of prescribed drugs should be reduced by 40% by 2005, and that baseline rates of errors will need to be established. However, a major problem with interpreting quantitative prescribing error studies, is that the definition of an error used by the researchers is often ambiguous or not given at all. Comparisons of error rates across the literature are therefore accompanied by significant uncertainty. Where definitions are given, there may be marked divergences among studies. A common approach has been to consider that a prescribing error has occurred if both doctor and pharmacist agree that this is the case. While pragmatic, this approach is limited by potential divergences in the knowledge and views of individual practitioners. Other studies have used outcome-based definitions, including as errors only those that result in harm to the patient. However, in many cases, pharmacists intervene to prevent errors from reaching the patient and so the outcome remains unknown. Even where prescribing errors are defined more explicitly, there is wide variation in the types of events included. For example, Betz and Levy include “prescribing a medication without sufficient education of the patient on its proper uses and effects” while Tesh et al include “the prescription of medication by brand (instead of generic) name”. Others do not consider these to be prescribing errors. Consequently, it is almost impossible to compare data from divergent studies or to use prescribing error rates as a meaningful component of clinical governance. If alternative prescribing systems are to be evaluated in terms of their effects on prescribing error rates, a clear definition is needed. Thirty four (79%) of those approached agreed to take part. These comprised nine physicians, three surgeons, 12 pharmacists, seven nurses, two clinical pharmacologists, and an anaesthetist. A wide range of clinical specialities were represented; nine of the panel had extensive experience of medication error research and one was the editor of a relevant peer reviewed journal. In the first Delphi stage, responses were received from 30 (88%) of the 34 judges. Responses to the second stage were received from 26 (87%) of the 30 judges to whom second stage questionnaires were sent. When asked for their opinion on the definition proposed, the judges’ median score was 7.0 and the inter-quartile range 6.5–8.0. This indicates that the consensus was to accept the researchers’ preliminary definition. Many additional comments were made relating to this definition, most of which fell into three categories. Firstly, four respondents were unsure whether errors in the prescribing decision should be included as well as those in the prescription writing process. These judges considered the prescribing decision to be part of a broader concept of “clinical decision making” rather than “prescribing”. However, other respondents emphasised the importance of including both elements of the definition, and it was concluded that both should remain. Secondly, six judges were concerned about the use of the word ‘significant’ and considered that the inclusion of this word meant that the definition was only of a “serious” prescribing error. However, others felt that this word should be included for two reasons:

- it was considered important to differentiate between clinically meaningful prescribing errors and those cases where some optimisation of treatment was possible but where a prescribing error could not be said to have occurred;

- it was recognised that cognitive errors could occur in the prescribing process without there being any adverse consequences for the patient.

For example, a doctor may prescribe drug X instead of the intended drug Y, but if both are equally safe and effective then the cognitive error is not clinically important. It was therefore considered that the word ‘significant’ was necessary, but that it should be made clear that the definition is of a “clinically meaningful” prescribing error. Finally, three judges indicated that a comparator was needed within the definition as “reduction” and “increase” implied a baseline. It was therefore decided to add a statement to this effect. The definition of a prescribing error finally adopted was therefore: “A clinically meaningful prescribing error occurs when, as a result of a prescribing decision or prescription writing process, there is an unintentional significant reduction in the probability of treatment being timely and effective or increase in the risk of harm when compared with generally accepted practice”. Using the Delphi technique, a general definition of a prescribing error has been developed together with guidance concerning the specific types of event that should be included. This is practitioner led, more detailed than the definitions used in previous studies, and concordant with human error theory. According to theories of human error, a series of planned actions may fail to achieve their desired outcome because the plan itself was inadequate or because the actions did not go as planned. Our definition reflects this distinction while including failures in the prescribing decision as well as the prescription writing process.

Pharmacy in New Age

The ‘Pharmacy in a New Age’ discussions also led to the understanding that without government support and encouragement improvements in community pharmacy practice would not be achieved (Longley 2006). The willingness to change expressed by the profession empowered the Pharmacy Services Negotiating Committee and the Department of Health discussions. These discussions produced a new pharmacy contract which could reward new non-dispensing services and reflected the aspirations expressed by the pharmacy profession in the ‘Pharmacy in a New Age’ report (Department of Health 2005; Parkin 1999).

The new pharmacy contract introduced in 2005 allowed for three different levels of community pharmacy services (Department of Health 2005). The core dispensing, health promotion and self medication roles were classed as ‘essential services’ to be supplied by all pharmacy contractors (Department of Health 2005a). ‘Advanced services’ could be offered by all pharmacies, subject to specified criteria, offering more clinical services on to a national service specification (Department of Health 2005b). At present there is only one advanced service, the Medication Use Review. The third level of service incorporated in the new contract allows local NHS organisations to commission ‘enhanced services’ to satisfy local needs. Examples of local enhanced services include emergency hormonal contraception and the minor ailments scheme.

The government around this time asked Dr. Crown to review the prescribing, supply and administration of medicines in the UK (Department of Health 1999; Parkin B 1999). Changes were suggested to allow a new category of prescriber, supplementary, who would prescribe for long term conditions under the supervision of an independent, usually medical prescriber. Initially supplementary prescriber status was restricted to suitably trained nurses but training and qualification were extended to include pharmacists.

Non-medical prescribing is an initiative introduced by the National Health Service that was designed to encourage healthcare professionals to expand their breadth of knowledge and to improve positive health-related outcomes for patients (Cooper et al. 2008a). As I have always been interested in increasing my ability to positively influence patient’s health I became the first community pharmacist supplementary prescriber in Dorset. Supplementary prescribing requires the prescriber to treat patients to a Clinical Management Plan which specifies patient condition, drugs to use, referral conditions and requires annual review by the independent prescriber. The Clinical Management Plan is the basis of prescribing practice among the independent and supplementary prescribers. Satisfactory experience with non-medical supplementary prescribing led to the introduction of independent prescribing status for suitably trained non-medical prescribers. In the United Kingdom since the establishment of the National Health Service the administration of medications and drugs to patients has been based on instructions from a doctor or dentist. The legal basis for supply of medicines to the public was regulated by the government (Department of Health 1968). The importance of over the counter medication and the role of the pharmacist in controlling access to some medicines with medicines being classified as being freely available for sale (the General Sales List), available from pharmacies (P medicines) and restricted to prescription (POMs or prescription only medicines).

In response to a global need to increase access to POM medication legal changes have been made by the Department of Health which extended the right to prescribe to suitably qualified members of both the nursing and pharmacy professions (Emmerton et al. 2005). The government found it necessary to introduce prescribing policy changes to increase access to commonly prescribed medicines to reduce the workload of doctors. It was hoped that by allowing non-medical prescribing for patients suffering from long term conditions, doctors would be able to produce savings by reducing the delay on diagnosis of newly presenting conditions.

It was felt necessary to initiate fresh forms of prescribing in NHS methods in order to facilitate health professionals, who were not from the health field, to have the prescription rights. Following lobbying and consultations among the government, the various healthcare professions and concerned patient groups an inquiry was initiated into the issue. Dr. Crown was asked to review the prescribing, supply and administration of medicines in the UK and propose improvements to the current system (Department of Health 1999). Changes were suggested to allow a new category of prescriber, supplementary, who would prescribe for long term conditions under the supervision of an independent, usually medical prescriber. Initially supplementary prescriber status was restricted to suitably trained nurses but, following satisfactory experience with nurse prescribing, training and qualification were extended to include pharmacists.

Non-medical prescribing is an initiative introduced by the National Health Service that was designed to encourage healthcare professionals to expand their breadth of knowledge and to improve positive health-related outcomes for patients (Cooper, Anderson, Bissell, Guillaume, Hutchinson, James, Lymn, McIntosh, Murphy, Ratcliffe, Read, & Ward 2008a). Supplementary prescribing requires the prescriber to treat patients to a patient specific Clinical Management Plan which defines the patient condition, drugs to use, referral conditions and requires annual review by the independent prescriber. The Clinical Management Plan is the basis of prescribing practice among the independent and supplementary prescribers. Supplementary prescribing is based on a three way agreement between the patient, independent prescriber and supplementary prescriber producing a bureaucratic complication to the supply of medicines. Concerns about the limitations of this tripartite model of supplementary prescribing led moves to develop another prescribing model which could encompass all allied health professionals. Allied health professionals felt insufficiently empowered and subjected to restrictions due to the need to implement the clinical management plan approved by their independent prescriber when making prescribing decisions. Satisfactory experience with the prescribing of non-medical supplementary prescribing led to the introduction of independent prescribing status for suitably trained non-medical prescribers.

An example and the research Undertaken

“Independent Prescribing at Highcliffe Medical Centre”

Overview

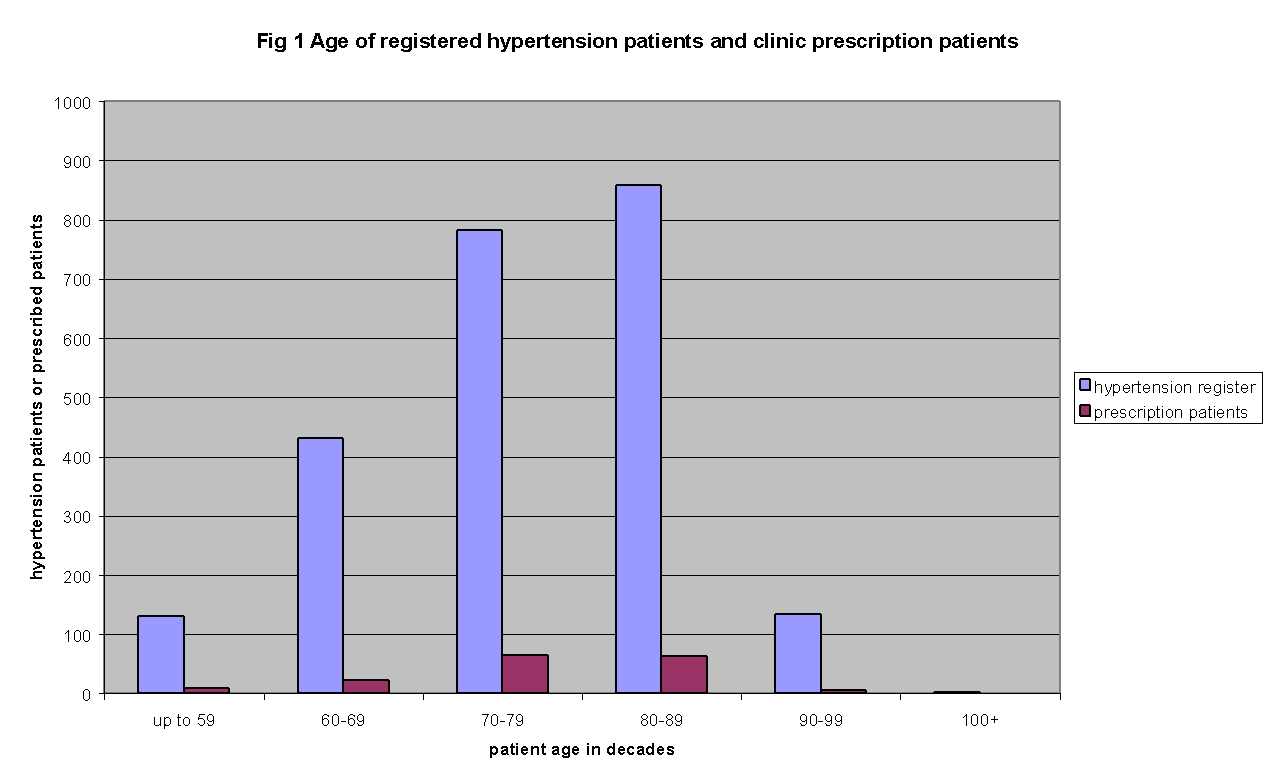

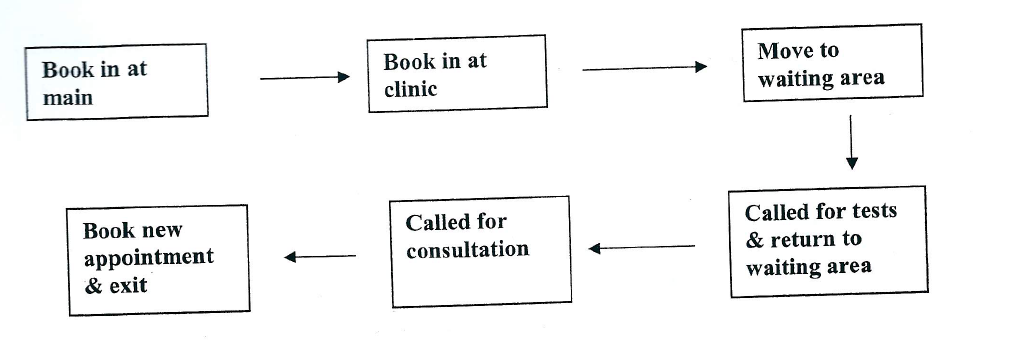

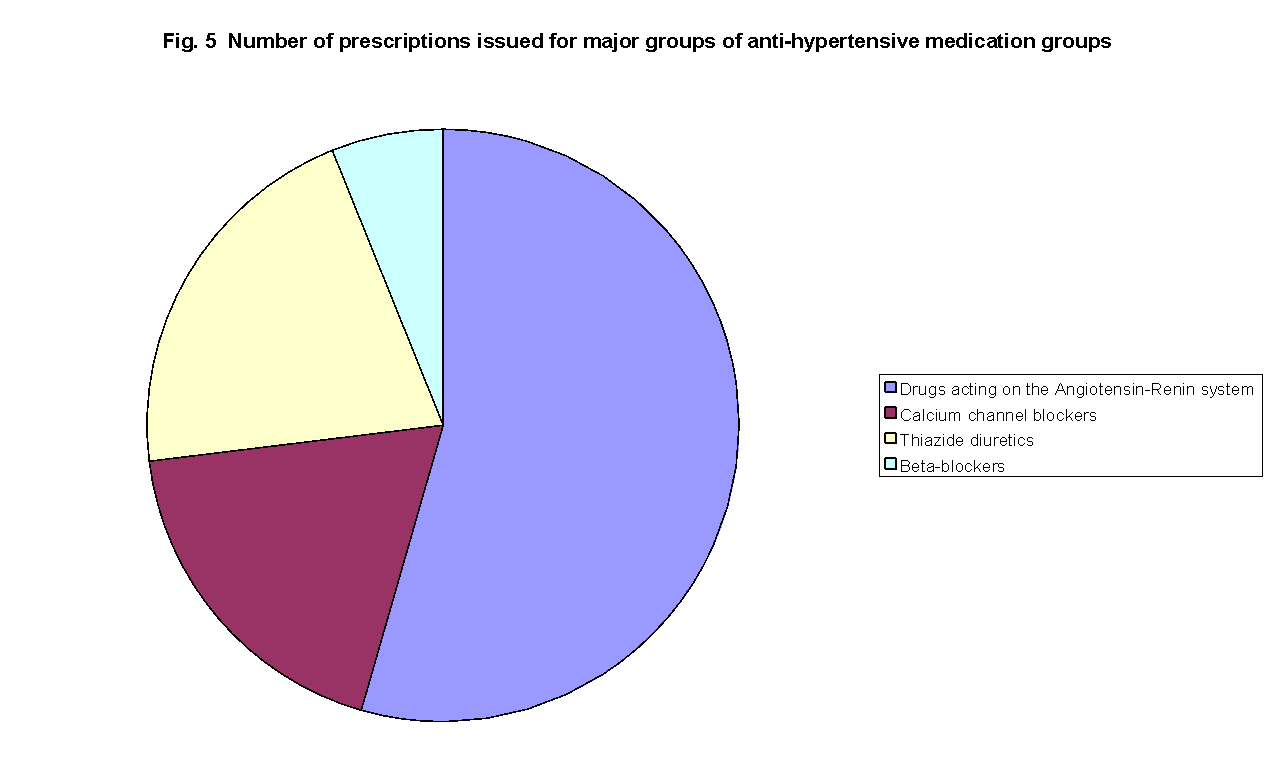

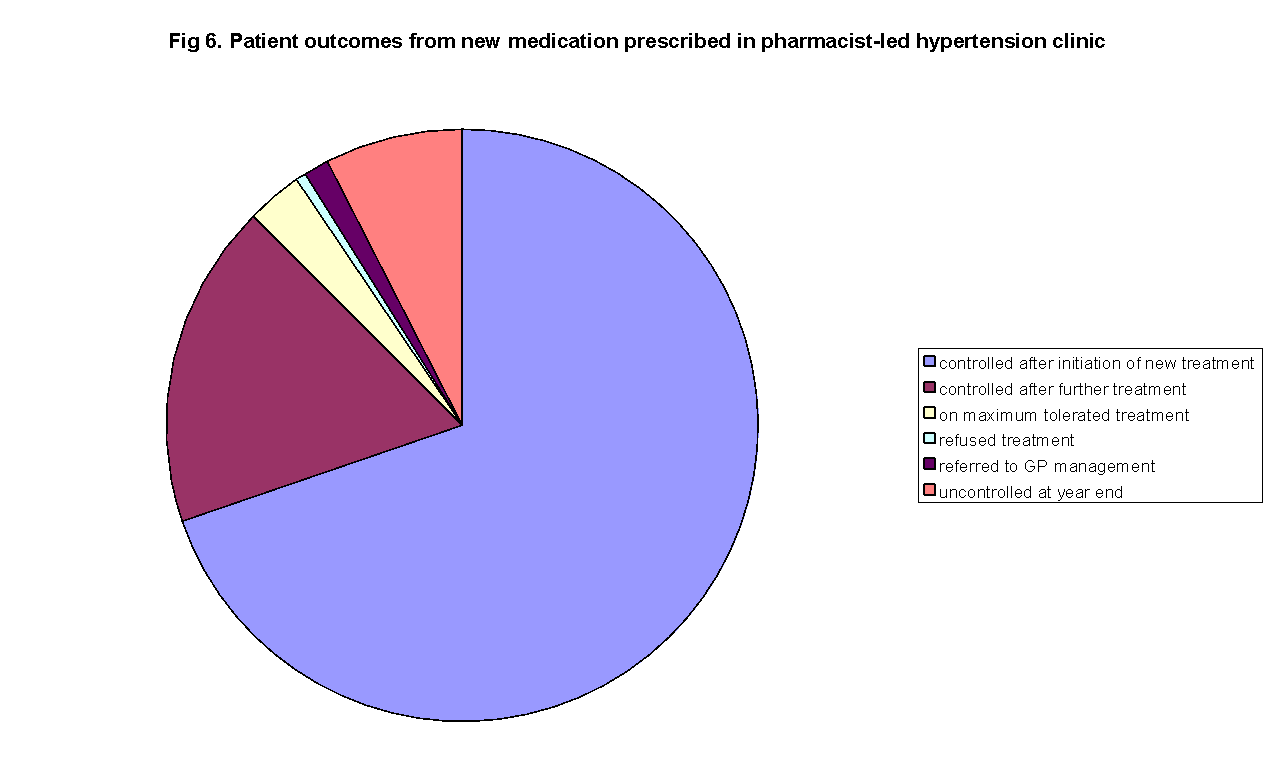

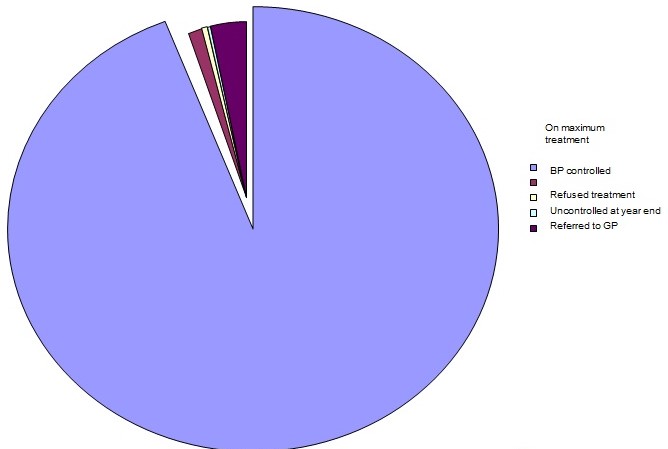

The case involves a pharmacist at a prescribing role at the medical centre. He had been at work at Highcliffe Medical Centre since 2004, initially as a trainee supplementary prescriber and subsequently as a qualified supplementary prescriber. The person attained the qualification as an independent prescriber in January 2008. Highcliffe Medical Centre practice was a specialist hypertension clinic where the pharmacist prescriber had full access to the patient’s medical records. The pharmacist also worked in the pharmacy based within the Medical Centre and following discussions with the Medical Centre and the local Primary Care Trust, the local National Health Service organisation, performed the new pharmacy contract Medication Use Reviews based at the Medical Centre. In 2005, the National Health Service of the UK introduced a new contract for community pharmacies which recognised three levels of pharmacy service: ‘basic or core services’, ‘advanced services which are commissioned on a national basis’ and ‘enhanced services which are commissioned to fulfil local needs’. The reviews are performed face to face with the patient and aim to increase concordance with treatment plans through improved patient education and identification of adverse effects to prescribed medication. These reviews were performed in the Medical Centre with access to the patient’s medical records and could include when necessary measurement of blood pressure in response to clinical system prompts. In this way, blood pressure recording was incorporated into Medication Use Reviews and for patients taking only blood pressure medication, Medication Use Reviews into hypertension clinics.

Patients are usually referred to the pharmacist following blood pressure measurement by one of the Medical Centre nurses or healthcare assistants in accordance with the practice protocol. When these members of the nursing team found it necessary to have a second appointment to confirm raise blood pressure and increase treatment the pharmacist-led clinic was an alternative to referral to a doctor. A second route for patient referral to the hypertension clinic is following a routine review of patient medical records by one of the Medical Centre doctors. For the Saturday morning ‘workers’ sessions, patients are invited to attend by letter following a review of a clinical system report listing details of time since last review, patient age and last recorded blood pressure. Finally, patients who are seen in Medication Use Reviews by the pharmacist prescriber may have their blood pressure checked if their medical record indicates this is required. If the blood pressure was found to be raised during the Medication Use Review these patients are referred for follow-up to the hypertension clinics.